Background and Objectives: The influence of racism in medicine is increasingly acknowledged, and the negative effect of systemic racism on individual and population health is well established. Yet, little is known about how or whether medical students are being educated on this topic. This study investigated the presence and features of curricula related to systemic racism in North American family medicine clerkships.

Methods: We conducted a survey of North American family medicine clerkship directors as part of the 2021 Council of Academic Family Medicine’s Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey.

Results: The survey response rate was 49% (78/160). Almost all clerkship directors agreed (n=68; 97.1%) that teaching about racism at all levels of medical education was appropriate. Yet, 60% (n=42) of family medicine clerkship directors reported no formalized curriculum for teaching about racism or bias. Teaching about systemic racism was more likely to be present in the family medicine clerkship at institutions where clerkship directors reported that faculty receive 5 or more hours of training in racism and bias, as compared to institutions where faculty receive 4 or fewer hours of training in racism/bias (odds ratio 2.82, 95% CI 1.05-8.04, P=.045). Programs reported using racism in medicine curricula based in cultural competency (20%); structural competency (10%); both cultural and structural competency (31%); and neither or uncertain (40%). Clerkship directors reported high faculty, student, and institutional engagement in addressing systemic racism. We did not find an association between underrepresented in medicine director identity and racism curricula.

Conclusions: In more than half of family medicine clerkships, systemic racism is not addressed, despite interest from students and institutional support. A higher number of hours of faculty training time on the topic of racism was associated with having a systemic racism module in the clerkship curriculum, but we lacked data to identify a causal relationship. Investments in faculty development to teach systemic racism, including discussion of structural competency, are needed.

The influence of racism in medicine is increasingly discussed in the family medicine, internal medicine, pediatric, and surgical scientific literature. 1-10 National organizations including the American Medical Association,11 American Board of Family Medicine, 12 Association of Departments of Family Medicine, 13 Society of Teachers of Family Medicine, 4 American College of Physicians, 2 American College of Surgeons, American Academy of Pediatrics, 10 and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention14 have called for action to mitigate the influence of systemic racism in medicine.

The negative effect of systemic racism on individual and population health is well established. 15, 16 Systemic racism, also called “structural racism,” includes all levels of racism—institutional, personally-mediated, and internalized—and is the root cause of racial health inequities. The intergenerational impact of decisions made about housing, zoning, infrastructure, medicalization, and more, along with established explicit and implicit racist beliefs and attitudes, have damaged health through multiple causal pathways. 17-21 For example, recent studies have drawn a direct link between historical racist redlining practices and the presence of increased levels of environmental toxins in communities of color today. 22

Evidence also suggests that medical students, residents, and physicians demonstrate implicit racial bias. These are automatic mental associations about racial groups, a byproduct and reflection of systemic racism, that favors White patients over Black patients and other patients of color. 23 Teaching medical students, residents, and faculty about the impact of racism from the past to the present, including the interconnected levels of racism, both seen and unseen, is therefore important. However, available evidence suggests that content on the health impact of systemic racism has been largely absent from medical curricula. 24

Meanwhile, stereotypes and biases may be promoted, and racist beliefs entrenched, when racial health inequities are taught without intentional instruction about their root causes. 25-27 Review of the literature suggests that medical curricula often harbor misrepresentations of race, such as lessons that teach race as a genetic proxy rather than as a social construct. 28-29 Race-based guidelines are still also widely taught without adequate exploration of the strength of evidence informing the guidelines. 30- 31

Recent calls for action have recognized the dearth of high-quality teaching about racism in medical education and have charged medical schools with developing antiracism, systemic racism, and racism-in-medicine curricula. Moreover, trends in antiracist pedagogy have arguably shifted 32 from the cultural competency framework, which emphasizes multiculturalism and diversity without an explicit link to racism, bias, and structured power relations, 33, 34 to structural competency, which emphasizes “forces that influence health outcomes at levels above individual interactions.” 17 In 2020, Gutierrez reported that numerous medical schools quickly implemented antiracist curricula. 35 Anecdotally, the experiences of our research team are in alignment with such an observation, although we were unable to find published studies that support the claim. We are also unaware of any studies that systematically evaluated the content and theoretical framework of these new, “quickly implemented” curricula.

In this study, we sought to investigate the presence and features of curricula related to systemic racism in North American medical schools. Family medicine clerkships were sampled to represent current teaching in medical schools, because family medicine clerkships have long embraced teaching about social determinants of health. We hypothesized that most family medicine clerkships would include some curricular content related to the influence of racism and that most would be using a cultural competency framework, rather than a structural competency framework. We further hypothesized that the presence of any structural racism curriculum would be influenced by clerkship director beliefs and identity, and program characteristics.

Survey Development and Measures

We conducted a survey of North American family medicine clerkship directors as part of the 2021 Council of Academic Family Medicine’s (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey. 36, 37 The survey obtains information about director demographics, professional characteristics, clerkship structure (duration, block vs longitudinal design, etc) and medical school environment (number of students, etc).

We further collected data on (1) the existence of systemic racism curricula and how long ago they were developed, (2) the framework (cultural competency vs structural competency) used, (3) student and faculty training hours related to structural racism/bias, (4) faculty and institutional attitudes toward teaching about systemic racism, (5) the appropriate setting for teaching about structural racism (preclinical vs clinical, etc), (6) available resources for teaching about systemic racism, (7) student interest and engagement with existing clerkship racism/bias content, and (8) level of importance assigned by the director to expanding clerkship content.

Survey questions were developed by faculty within our family medicine department with diverse professional interests: medical student education, resident education, research, outpatient medicine, inpatient medicine, and clinical psychology. Questions were externally reviewed by the CERA committee, and modifications were made in response to feedback.

Survey Implementation and Participants

The annual CERA survey structure, scope, and processes have been described in detail previously. 36, 37 The 2021 survey was distributed between April 29, 2021 and May 28, 2021 via email invitation to all of the 163 individuals identified as educators directing a family medicine or primary care clerkship (with family medicine component) that are accredited by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Three were undeliverable, resulting in 160 delivered invitations. Five changes to the clerkship director were identified, and all five new clerkship directors were then invited to participate in the survey. Nonrespondents received three weekly requests, plus one final request at 2 days before closing the survey.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics using R software version 3.6.1 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria). We interrogated associations between the existence of systemic racism curricula and continuous and/or two-level variables including (1) greater faculty bias/racism training time, (2) medical school class size, and (3) underrepresented in medicine (defined as race other than White and/or non-Hispanic ethnicity) clerkship director using bivariable logistic regression. For faculty training time, we quantized data into two levels: 4 hours or less vs 5 hours or more. We tested associations between the existence of structural racism curricula and census region (Northeast, Midwest, West, South) and Canada using Fisher’s exact test. All statistical comparisons were prespecified. The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Respondent Characteristics

We received survey responses from 78 of 160 surveyed clerkship directors (response rate 49%). We excluded from analysis three surveys left almost entirely blank and four surveys without responses for the systemic racism questions, leaving 71 responses included in the analysis. Respondent characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Excluded respondents were generally similar to respondents. Directors were most likely to be female (58%), cisgender (99%), White (74%) or Asian (14%), non-Hispanic (96%), and physicians (99%). Directors had held their position for widely varied durations (about evenly divided between 0-2 years, 3-5 years, 6-9 years, and 10 years or more; median 5 years; IQR 2-9 years). Most clerkships were designed for third-year medical students (86%), had a block structure (sequential weeks of full-time study, 72%), and were mandatory (99%). Public (63%) and private (37%) institutions were both well represented. Clerkships were drawn from all census divisions (Table 1) and had a wide range of medical student class sizes (median 160 students, IQR 103-180).

|

Characteristic

|

n (%)

|

|

Director Gendera

Cisgender female

Cisgender male

Transgender male

Decline

|

...

41 (57.7)

27 (38.0)

1 (1.4)

2 (2.8)

|

|

Director Race

Asian

Black

Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander

White

Multiple

Not reported

|

...

10 (14.3)

5 (7.1)

1 (1.4)

52 (74.3)

2 (2.9)

1

|

|

Director Ethnicity

Not Hispanic

Hispanic

|

...

68 (95.8)

3 (4.2)

|

|

Is Director a Physician?

Yes

No

|

...

71 (100)

—

|

|

Years Served as Clerkship Director

0-2 years

3-5 years

6-9 years

10 years or more

|

...

19 (26.8)

19 (26.8)

17 (23.9)

16 (22.5)

|

|

Year in Medical School of Family Medicine Clerkship

Second year

Third year

Second and third years

Third and fourth years

|

...

1 (1.4)

61 (85.9)

4 (5.6)

5 (7.0)

|

|

Clerkship Design

Block only

Longitudinal only

Both block and longitudinal

|

...

51 (71.8)

4 (5.6)

16 (22.5)

|

|

Is Clerkship Mandatory?

Yes

No

|

...

70 (98.6)

1 (1.4)

|

|

Public or Private School?

Public

Private

|

...

45 (63.4)

26 (36.6)

|

|

Census Division/Country

Northeast

South

East North Central

West

Canada

|

...

13 (18.3)

32 (45.1)

16 (22.5)

6 (8.5)

4 (5.6)

|

|

Class Size

1-99

100-155

156-180

181-300

|

...

16 (22.5)

19 (26.8)

21 (29.6)

15 (21.1)

|

|

Percentage of Class Matching Into Family Medicine

5% or less

6% - 10%

11% - 15%

|

...

14 (19.7)

29 (40.8)

14 (19.7)

|

Most Family Medicine Clerkships Have No Formal Curriculum for Systemic Racism

Program directors almost universally agreed (n=68, 97.1%) that teaching about racism is appropriate at all levels of education: premedical, preclinical and clinical, and in both required and elective settings (See Appendix Table 1). Nonetheless, 60% (n=42) of family medicine clerkships reported having no formalized racism or bias curriculum.

Of clerkships that reported having a formal racism curriculum (n=28), a majority (n=21, 75%) developed their curricular content within the last 5 years. Most respondents (n=50, 72%) reported their clerkship curriculum contained 1 hour or less of any instruction related to racism or bias for their students. Just more than half of directors (n=35, 51%) reported they had received more than 5 hours of training or development on racism or bias themselves. Only eight clerkship directors (12%) reported receiving no training related to this topic.

Directors Reported High Faculty, Student, and Institutional Engagement in Addressing Systemic Racism

When asked what proportion of their faculty colleagues “believe that systemic racism and bias contribute significantly to health disparities,” two-thirds of respondents (n=45, 67%) selected 80%-100%. Directors also reported that they believed students to be interested in learning about systemic racism (n=65, 94% report some, moderate, or high interest), and many directors reported that students were interested, engaged, or curious about this topic (33%). Only one director (1.4%) reported receiving active pushback from students when teaching about systemic racism and bias. Most directors perceived they had institutional encouragement to teach about systemic racism (n=57, 81%) but of those, only about half (n=30, 53%) reported availability of significant resources to do so. No director believed that their institution discouraged discussing systemic racism. We are aware, however, that since this survey closed, some state legislatures have passed legislation prohibiting the teaching of some types of racism curricula.

Approaches, Capacity, and Priorities Related to Systemic Racism Vary Extensively

We investigated two theoretical frameworks used for teaching about racism and/or bias, cultural competency, and structural competency, and found variability. Twenty percent of respondents reported using cultural competency, 10% reported using structural competency, and 31% of reported using both frameworks. Twenty-seven percent were uncertain what framework they used or felt the use of a framework was not applicable. Another 13% reported they “teach about health inequities without using terms like bias or racism.”

We also found variability in faculty teaching capacity. We asked directors to estimate the number of educators they could call on who were both qualified and comfortable teaching about systemic racism and bias. Most directors reported that they could call upon at least one qualified teacher (79%). A significant minority of directors reported more than five qualified individuals were available (24%). A similar proportion of directors (about one in five, 22%) reported they could not identify a single faculty member to teach the course.

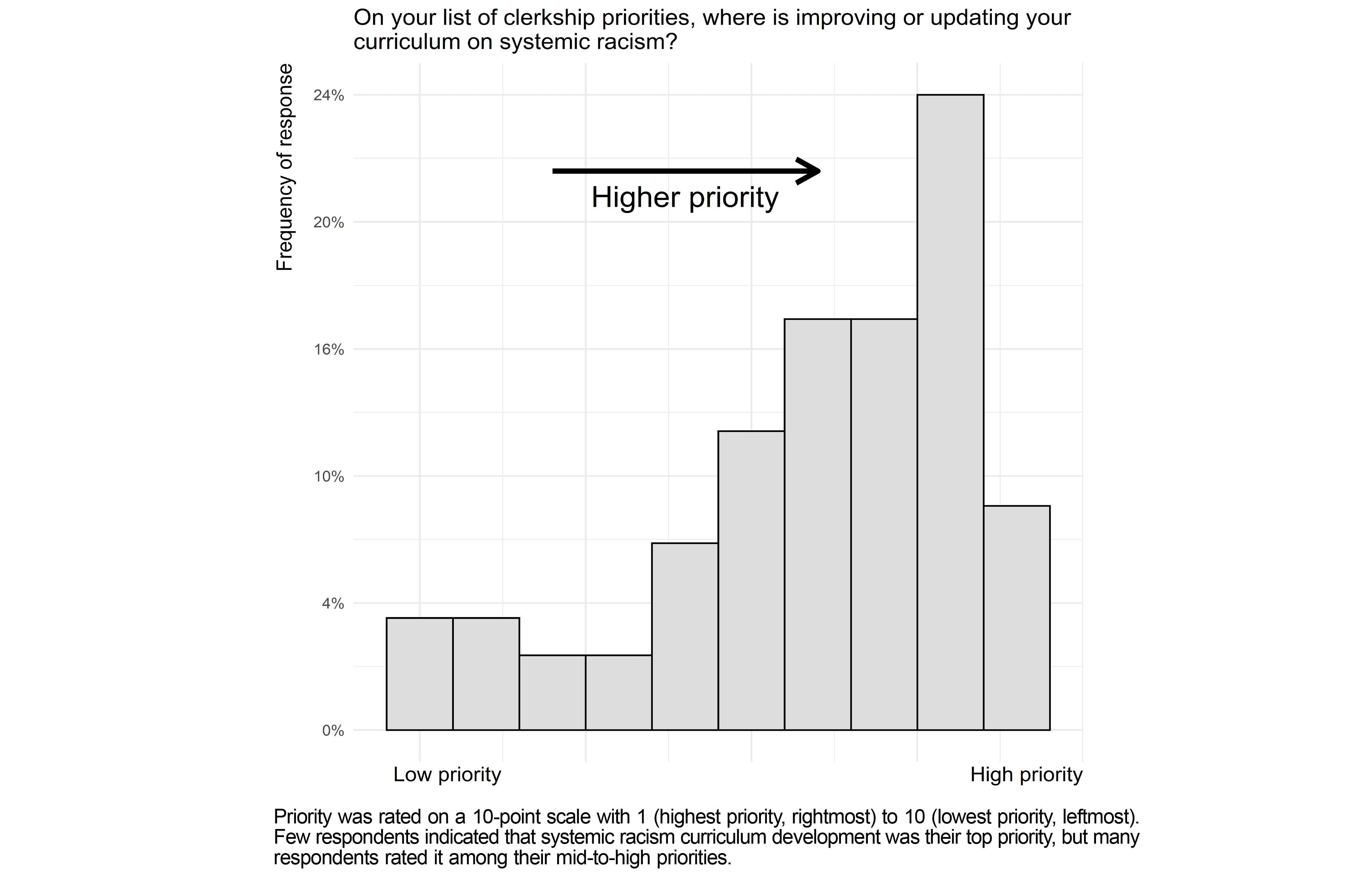

We found additional variability in how strongly clerkship directors prioritized systemic racism curricular development (Figure 1). Few clerkship directors rated bias/racism curricular development as their top priority (six of 68 directors, 9%, rating curricular development a 1 out of 10), but half of directors rated curricular development as high priority (50% rating 1-3). Many also rated it as a moderate priority (38% rating 4-7). Few directors viewed development of systemic bias curriculum as very low priority (11% rating 8-10).

Systemic Racism Curricula Are Associated With Greater Faculty Bias/Racism Training Time

We evaluated whether there were factors associated with the existence of systemic racism curricula (stratified distributions shown in Appendix Table 2). Specifically, we tested whether the presence of a racism curriculum in the clerkship was associated with (1) greater faculty bias/racism training time, (2) medical school class size, (3) region, or (4) clerkship directors who are underrepresented in medicine. We found a significant association for the first factor. Systemic racism curricula was more likely to be present in the clerkship at institutions where directors reported that faculty receive 5 or more hours of training in racism and bias, as compared to institutions where faculty receive 4 or fewer hours of training (odds ratio [OR] 2.82, 95% CI 1.05-8.04, P=.045). We did not find an association between medical school class size (OR 0.91 per 50 students, 95% CI 0.59-1.39, P=.67), underrepresented in medicine clerkship director (OR 0.59, 95% CI 0.18-1.74, P=.35) or census region (Fisher’s exact test P=.67). Among clerkships reporting the presence of systemic racism/bias curricula, six of 28 (21%) were being lead by an underrepresented-in-medicine clerkship director (Appendix Table 2).

We had hypothesized that the presence of a systemic racism curriculum would correlate with director belief that teaching about systemic racism is appropriate in the family medicine clerkship. Because there was no variance in director belief, we could not test this hypothesis.

North American family medicine clerkship directors in this study agreed (97%) that teaching systemic racism is appropriate at all levels of medical education. Sixty percent of reporting clerkships, however, had no formal curriculum for systemic racism, and 41% devoted no time to teaching the topic, despite reporting high student interest and institutional support. Without formal curricular inclusion of the history and impact of systemic racism as a root cause of health inequities, misperceptions may be reinforced among learners that these inequities are naturally occurring or caused by the people who experience them. Medical students and trainees are consistently taught that patients of color experience higher rates of disease with worse outcomes. Without explicitly discussing the root causes of these inequities many wrongly conclude that race is a genetic determinant of health, potentially furthering physiological race myths. 38

The family medicine literature contains rich discussions about systemic racism. 39, 40 Both educators and learners are demanding formal medical education on the topic. 41, 42-45 As a discipline, family medicine has historically placed a focus on health equity and social justice, and its leaders have declared their dedication to addressing systemic racism. 40, 46 The Society of Teachers of Family Medicine National Clerkship Curriculum includes social and structural determinants of health among its learning objectives. 47 It follows that family medicine would be a leader in teaching about the health effects of racism. However, our results found that only 40% of family medicine clerkships include a formal racism curriculum. We were nonetheless encouraged to have found that the majority (75%) of directors reporting that their clerkship contained formal racism curricula have developed these curricula within the past 5 years. We interpret this as progress.

Clerkships do not need to start from scratch when developing these curricula. Toolkits for teaching about structural racism in medical school have been published and presented at recent conferences. 48-55 Clerkships also likely have access to teaching resources internally. In this study, nearly 80% of responding clerkship directors said they could identify a qualified faculty member to teach about systemic racism.

Faculty development is needed, in addition to curriculum development, to both promote the presence of these curricula and to ensure their high quality. Again, we found that a higher number of hours devoted to faculty training time on the impact of racism was significantly correlated with having a structural racism module in the clerkship. Although we can make no causal inferences from this relationship, it seems likely both that people who have an interest in a topic are more likely to seek out related learning opportunities, and that further exposure to and practice with a topic facilitates curriculum development. Further research exploring this relationship may be fruitful.

The American Medical Association and the Association of American Medical Colleges released separate policy statements, both of which identify the need to ensure a high level of quality of new curricula on the influence of structural racism. 56, 57 The Society of Teachers of Family Medicine launched the Underrepresented in Medicine (URM) Initiative to increase the percentage of URM family medicine faculty by focusing on mentorship, leadership, scholarship, and the faculty pipeline. 58 To achieve high-quality curricula—those embracing structural competency beyond cultural competency, for example—the type of faculty development likely matters. In this study, clerkship directors indicated that a plurality of frameworks were still being used to teach racism at the clerkship level; roughly one-fifth were using cultural competency, one-tenth were using structural competency, one-third were using both, and almost one-third did not know what framework was being used to teach in their clerkship. Because racism is pervasive and impacts medicine and health at multiple levels (internalized, interpersonal, community, and institutional), 20, 21 learning and teaching about racism requires self-reflection, self-awareness, moving the unconscious to the conscious, and unlearning and reevaluating ideologies.59 Psychological safety is also required, for both the teacher in training and learner. Meaningful conversations about racism can trigger guilt, defensiveness, shame, and anger. 60, 61 Faculty development of this depth will take a significant time investment on the part of programs and institutions.

The strengths of our study included (1) the use of a multicenter, anonymous survey, which increased the generalizability of our data, and (2) a wide range of survey questions to gauge both attitudes toward and characteristics of the current state of systemic racism curricula. The limitations of our study included a concern for the relatively small response rate compared to other CERA rates. This concern may be adequately mitigated by underscoring that the survey population was a true population (all North American clerkship directors for family medicine/primary care) and not a sample. Nevertheless, we cannot fully exclude the possibility of nonresponse bias. Social desirability bias is a possible limitation of our study; clerkship directors may have overreported interest and support for teaching about systemic racism. Social desirability bias occurs when respondents answer survey questions in a way that is viewed favorably by others. Directors may have also inaccurately estimated their colleagues’ and students’ feelings in their responses.

Medical students and physician leaders are calling for formal education on systemic racism, and institutional support appears to be present. Our study suggests this teaching is still surprisingly underrepresented in clerkship curricula. More research, including qualitative designs, is needed to investigate barriers to adopting racism as a topic of focus within clerkship curricula. Skills and self-efficacy around teaching these topics in medical education may be low, leading to inaction or the use of outdated theoretical frameworks. Understanding these barriers is the next step to providing this education to generations of future physicians.

We recommend the creation of a national clerkship curriculum on systemic racism, which would standardize content across institutions. A national curriculum should (1) teach structural racism as a cause of health disparities, (2) shift away from the cultural competency framework to the structural competency framework, (3) encourage and equip family physicians and educators to lead this work at institutions and with colleagues in other disciplines and clerkships, and (4) challenge all our clerkships to teach antiracism as the major solution to health disparities in the United States. Medical trainees must learn about the root causes of racial health inequities, and they should learn these lessons in the context of their formal clinical clerkships.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Council of Academic Family Medicine’s Educational Research Alliance for administering the survey.

Author Contributions

†Drs Bridges and Rampon contributed equally to this study. #Drs Parente and Witt also contributed equally to this study.

Presentations

This study was previously presented as:Rampon K, Witt LB, Parente D, Bridges K, Born W. Systemic Racism is Addressed in Less than Half of Family Medicine Clerkships. Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference, Indianapolis, IN; May 2022.

References

-

Olayiwola JN. Racism in medicine: shifting the power. Ann Fam Med

. 2016;14(3):267-269. doi:10.1370/afm.1932

-

Serchen J, Doherty R, Atiq O, Hilden D; Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians. Racism and Health in the United States: A Policy Statement From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med

. 2020;173(7):556-557. doi:10.7326/M20-4195

-

-

Sexton SM, Richardson CR, Schrager SB, et al. Systemic racism and health disparities: a statement from editors of family medicine journals. Fam Med

. 2021;53(1):5-6. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.805215

-

Doubeni CA, Simon M, Krist AH. Addressing systemic racism through clinical preventive service recommendations from the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA

. 2021;325(7):627-628. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.26188

-

-

-

Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, Bassett MT. How structural racism works-racist policies as a root cause of U.S. racial health inequities. N Engl J Med

. 2021;384(8):768-773. doi:10.1056/NEJMms2025396

-

Evans MK, Rosenbaum L, Malina D, Morrissey S, Rubin EJ. Diagnosing and treating systemic racism. N Engl J Med

. 2020;383(3):274-276. doi:10.1056/NEJMe2021693

-

Trent M, Dooley DG, Dougé J, et al; SECTION ON ADOLESCENT HEALTH; COUNCIL ON COMMUNITY PEDIATRICS; COMMITTEE ON ADOLESCENCE. Section on Adolescent Health; Council on Community Pediatrics; Committee on Adolescence. The impact of racism on child and adolescent health. Pediatrics

. 2019;144(2):20191765. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-1765

-

-

-

-

-

Institute of Medicine Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care.

National Academies Press; 2003.

-

Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet

. 2017;389(10077):1453-1463. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X

-

-

Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One

. 2015;10(9):e0138511. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138511

-

Braveman PA, Arkin E, Proctor D, Kauh T, Holm N. Systemic and structural racism: definitions, examples, health damages, and approaches to dismantling. Health Aff (Millwood)

. 2022;41(2):171-178. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01394

-

Jones CP. Toward the science and practice of anti-racism: launching a national campaign against racism. Ethn Dis

. 2018;28(1)(suppl 1):231-234. doi:10.18865/ed.28.S1.231

-

Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health

. 2000;90(8):1212-1215. doi:10.2105/AJPH.90.8.1212

- Lane HM, Morello-Frosch R, Marshall JD, Apte JS. Historical redlining is associated with present-day air pollution disparities in U.S. cities. Environ Sci Technol Lett. 2022;9(4):345-350. doi:10.1021/acs.estlett.1c01012

-

-

Ona FF, Amutah-Onukagha NN, Asemamaw R, Schlaff AL. Struggles and tensions in antiracism education in medical school: lessons learned. Acad Med

. 2020;95(12S Addressing Harmful Bias and Eliminating Discrimination in Health Professions Learning Environments):S163-S168. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003696

-

-

-

Capers Q IV, Clinchot D, McDougle L, Greenwald AG. Implicit racial bias in medical school admissions. Acad Med

. 2017;92(3):365-369. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001388

-

Amutah C, Greenidge K, Mante A, et al. Misrepresenting race - the role of medical schools in propagating physician bias. N Engl J Med

. 2021;384(9):872-878. doi:10.1056/NEJMms2025768

-

Nolen L. How medical education is missing the bull’s-eye. N Engl J Med

. 2020;382(26):2489-2491. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1915891

-

Sjoding MW, Dickson RP, Iwashyna TJ, Gay SE, Valley TS. Racial bias in pulse oximetry measurement. N Engl J Med

. 2020;383(25):2477-2478. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2029240

-

Diao JA, Inker LA, Levey AS, Tighiouart H, Powe NR, Manrai AK. In search of a better equation - performance and equity in estimates of kidney function. N Engl J Med

. 2021;384(5):396-399. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2028243

-

-

Kumagai AK, Lypson ML. Beyond cultural competence: critical consciousness, social justice, and multicultural education. Acad Med

. 2009;84(6):782-787. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a42398

-

Beagan BL. Frisby CL & O’Donohue WT, eds. Cultural Competence in Applied Psychology: An Evaluation of Current Status and Future Directions. (Vol. 2018, pp. 123-138) Springer International Publishing

-

-

Cochella S, Liaw W, Binienda J, Hustedde C. CERA: clerkships need national curricula on care delivery, awareness of their NCC gaps. Fam Med. 2016;48(6):439-444.

-

Bryce C, Kam-Magruder J, Jackson J, Ledford CJW, Unwin BK. Palliative care education in the family medicine clerkship: a CERA study. PRiMER Peer-Rev Rep Med Educ Res

. 2018;2:20. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2018.457651

-

Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Axt JR, Oliver MN. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA

. 2016;113(16):4296-4301. doi:10.1073/pnas.1516047113

-

Freeman J. Something old, something new: the syndemic of racism and COVID-19 and its implications for medical education. Fam Med

. 2020;52(9):623-625. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.140670

-

Sexton SM, Richardson CR, Schrager SB, et al. Systemic racism and health disparities: a statement from editors of family medicine journals. Ann Fam Med

. 2021;19(1):2-3. doi:10.1370/afm.2613

-

-

-

-

-

Afolabi T, Borowsky HM, Cordero DM, et al. Student-led efforts to advance anti-racist medical education. Acad Med

. 2021;96(6):802-807. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004043

-

Schroeder SA. Social justice as the moral core of family medicine: a perspective from the Keystone IV Conference. J Am Board Fam Med

. 2016;29(1)(suppl 1):69-71. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2016.S1.160110

-

-

-

-

Brooks KC, Rougas S, George P. When race matters on the wards: talking about racial health disparities and racism in the clinical setting. MedEdPORTAL

. 2016;12:10523. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10523

-

White-Davis T, Edgoose J, Brown Speights JS, et al. Addressing racism in medical education: an interactive training module. Fam Med

. 2018;50(5):364-368. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.875510

-

Sotto-Santiago S, Hunter N, Trice T. A framework for developing antiracist medical educators and practitioner-scholars. Acad Med. 2021.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Borders A, Liang CT. Rumination partially mediates the associations between perceived ethnic discrimination, emotional distress, and aggression. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol

. 2011;17(2):125-133. doi:10.1037/a0023357

-

Diangelo R. White fragility. Int J Crit Pedagog. 2011;3(3).

There are no comments for this article.