Background and Objectives: The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the shortcomings of our health care delivery system for vulnerable populations and created a need to rethink health disparity education in medical training. We examined how the early COVID-19 pandemic impacted third-year medical students’ attitudes, perceptions, and sense of responsibility regarding health care delivery for vulnerable populations.

Methods: Third-year family medicine clerkship students at a large, private medical school in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania responded to a reflection assignment prompt asking how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted their thoughts about health care delivery for vulnerable populations in mid-2020 (N=59). Using conventional content analysis, we identified three main themes across 24 codes.

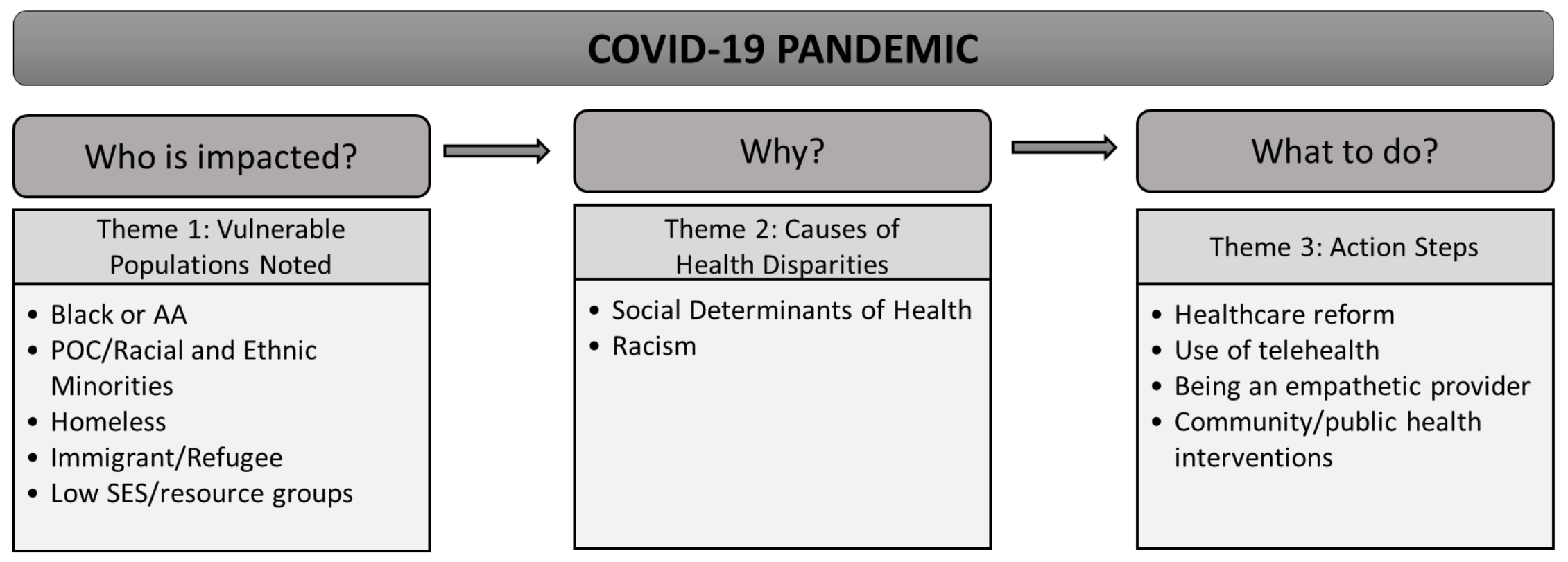

Results: Students recognized homeless individuals and Black, indigenous, and persons of color (BIPOC) as vulnerable populations impacted by the pandemic. Students reported causes of vulnerability that focused heavily on social determinants of health, increased risk for contracting COVID-19 infections, and difficulty adhering to COVID-19 prevention guidelines. Notable action-oriented approaches to addressing these disparities included health care reform and community health intervention.

Conclusions: Our findings describe an educational approach to care for vulnerable populations based on awareness, attitudes, and social action. Medical education must continue to teach students how to identify ways to mitigate disparities in order to achieve health equity.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted known health disparities resulting in disparate rates of morbidity and mortality across race/ethnicity and socioeconomic statuses. 1-3 This has led to national calls for the medical field to address its own structural racism and both conscious and unconscious biases. 4, 5 For medical educators, this includes addressing ways medical students understand, acknowledge, and feel responsible for tackling health disparities. For medical students this includes confronting inequities in healthcare and their communities and learning skills needed to address them.

Undergraduate medical education increasingly includes the social determinants of health (SDOH) and their impact on vulnerable populations. COVID-19 reduced many students access to in-person clinical experiences and generated a national conversation about health disparities. However, limited research has qualitatively explored how students are integrating knowledge about health disparities with the pandemic’s events to inform their attitudes and expectations for their patients.

Using principles of the Basic Behavior Change Framework (BBCF) to guide analyses, we explored how COVID-19 affected students’ awareness of health disparities and their capacity to address them. Broadly, the BBCF postulates that comprehensive knowledge change (the who, what, and why of health disparities populations) can impact one’s attitudes and awareness. This can then motivate behavior 6, 7 by developing a sense of responsibility to address concerns and spark downstream action. Our curricula includes training on quality improvement so that students have skills to translate attitudinal changes into action. Utilizing BBCF as a guide, our work centers on aspects of personal and social responsibility when analyzing medical students’ knowledge acquisition about health disparities faced by vulnerable populations. The goal of our study was to qualitatively examine how third-year medical students integrated their experiences during the COVID-19 into their training on health care delivery for vulnerable populations.

Medical Education Content

Prior to our curriculum development, a quality improvement (QI) curriculum was introduced to students during the family medicine clerkship. This QI curriculum included an Institute for Healthcare Improvement foundational course and a Plan Do Study Act video lesson, a problem-solving model for improving a process. After completion of an educational needs assessment, 8 we developed online, interactive modules on assessing community health needs, addressing health disparities, and care for vulnerable populations (eg, homeless, veteran, immigrant/refugee populations). 8, 9

Sample

Participants included two cohorts of third-year medical students completing their 6-week family and community medicine clerkship at a large, private medical school in Philadelphia, United States. Cohort 1 (n=29) was from June 15, 2020 to July 15, 2020, and Cohort 2 (n=30) was from July 20, 2020 to August 21, 2020. Five students did not respond, yielding a total response rate of 92% (n=59/64) and overall final analytic sample size of 59 students.

Procedures

Upon module completion, students completed a 10-item, short essay reflection assignment that comprehensively evaluates clerkship experiences and perceptions of their patients’ social determinants of health and health care. Data for this qualitative investigation utilized student responses to the prompt: “How has COVID-19 impacted your thoughts about healthcare delivery for vulnerable populations?” Essays were approximately 175-250 words in length and were submitted online via Canvas learning platform at the conclusion of the rotation. Students received training on the Integrated Reflective Model (IRM), 10 an approach to reflective essays that includes describing the experience, reflecting on what went well and what could be improved, contextualizing the experience in terms of their personal development or impacts on the field, and outlining how to prepare for future experiences. The Thomas Jefferson University Institutional Review Board approved all procedures.

Analysis

Four authors reviewed all responses, derived a list of codes from data, and used conventional content analysis 11 to guide generation of an initial codebook. After collaboratively coding 10 responses, the codebook was further refined and 24 codes were used for analysis yielding three overarching themes that map onto the BBCF 6, 7: vulnerable populations impacted, causes of health disparities, and actions necessary to improve care delivery (Figure 1). Two independent coders reviewed each response, and the team reconciled coding disagreements. Analysis included monitoring of differences across cohorts for any domains. However, there were no distinct differences between cohorts, therefore findings are not presented independent of each other. We used NVivo 12 software (QSR International Pty Ltd, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia) to manage and code data.

Sample Characteristics

Students in cohort 1 (n=29) were 58% female with a mean age of 25.8 years (SD=1.74). Students in cohort 2 (n=30) were 40% female but similarly had a mean age of 25.3 (SD=1.27). The race/ethnicities of the 2020-2021 medical student class are 64.3% White, 24.2% Asian, 6.5% Other, 2.5% Black or African American, 2.2% choose not to disclose, and 0.4% Pacific Islander.

Main Themes

Students described how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted their thoughts and perceptions on patients and health care delivery in three main themes: specific populations impacted, noted causes of health disparities, and changes necessary to improve care delivery for vulnerable populations (Table 1).

|

Theme

(Number of Students)

|

Exemplar Quotes

|

|

Theme 1. Knowledge: Who Are Vulnerable Populations?

|

|

Vulnerable Populations Noted (40)

|

“COVID 19 has disproportionately affected people of color, people of lower socioeconomic status and people experiencing homelessness. Though we may think that the disease is common to all people and that it does not care if a person is rich or poor, it is clear that treatment is not spread equally among all individuals. This is not a new phenomenon.”

|

|

Theme 2. Attitudes and Awareness: What Are the Contributors and Causes of Health Disparities?

|

|

Social Determinants of Health (50)

|

“Inequalities are perpetuated as minorities and individuals of lower socioeconomic status frequently work ‘essential jobs’ where they cannot work from home nor do they have access to adequate PPE. Yesterday in clinic, I saw an older African-American woman who was a CNA who had contracted the virus. She was dealing with all sorts of medical problems, was at an increased risk to begin with to have the virus, and had no financial freedom to not work. It was clear that she felt uncomfortable, but was without any other option.”

|

|

Racism (4)

|

“The pandemic has stressed healthcare's weakest points, and one of those is the healthcare disparities between populations. A huge portion of the driving force for disparities is racism and its institutionalization in healthcare has led to disproportionate amounts of people of color dying from the disease and suffering the worst outcomes. I think it comes as a surprise to no one that this is the case, but the thing is this was already happening before...and we were comfortable ignoring it. People of color were already dying en masse in greater numbers than whites, yet we allowed it to continue without a sense of urgency because it wasn't thrust in our face with the immediacy of a tangible public health risk like the virus.”

|

|

Theme 3. Action: What Needs to Be Done?

|

|

Health Care Reform (18)

|

“I think that healthcare delivery to vulnerable populations needs reform in order to better care for and protect the interests of all people, and not just those who have financial backing and privileged background needed to withstand a pandemic. This pandemic has put into perspective the importance of providing sustainable healthcare for all; I think that this needs to become a priority in order for change to be elicited on a national scale that could improve: 1) access to quality healthcare 2) delivery of quality healthcare to people in need, and especially those who are vulnerable in society who are affected disproportionately by the effects of the pandemic (both from a health as well as financial perspective).”

|

|

Use of Telehealth (17)

|

“I think telemedicine will be a good tool in giving vulnerable populations access to medical care where they may not have it already. For example, if there is no local doctor that speaks the language of a specific refugee, a doctor that does speak the language can see this patient via telemedicine. Patients that have trouble physically getting to a doctor will also benefit from telemedicine in being able to talk to their doctor. Additionally, social workers can go with iPads to vulnerable communities on specific days to allow doctors to give the people of these communities’ checkups even if they have not made appointments ahead of time.”

|

|

Empathetic Provider (9)

|

“I have a friend who is homeless that sits in front of my buildings on most days. We talk often and he plays with my dog when I take her on walks. Last Friday while I was on my way home from my shift, he looked more sad than normal. I got him his favorite soda and we sat on the street and talked for over an hour about his experience with COVID and homelessness. He has many health conditions that are poorly controlled, but he has been missing his personal identification for months at this point and is unable to get insurance coverage or his stimulus check and unemployment checks. This restricts him from going to a doctor’s office or using telehealth for his conditions. He is only left with acute care such as emergency rooms. Due to his health conditions, he is scared to use this service due to risk of COVID-19 exposure. He is now sitting on the streets untreated but without options for treatment. It was so heartbreaking to hear and I wish I had better solutions for homeless care during the pandemic.”

|

|

Community Health Intervention (8)

|

“Some people might not have access to parks in their neighborhoods to utilize for exercising, some might not have accessible markets to buy fresh fruit and vegetables from, and some might not have the financial security to voluntarily stay home to prevent the spread of diseases B9 (R18). We must remember that housing is healthcare, education is healthcare, and access to healthy food is healthcare. Healthcare delivery MUST improve for vulnerable populations and it is our responsibility as individuals in the medical community to advocate for that. Medical schools such as Jefferson should provide avenues for students to leverage this influence more easily--they need to establish existing programs so that we can help make an impact.”

|

Theme 1: Knowledge: Who Are Vulnerable Populations?

Homeless individuals were the most widely recognized group facing health disparities during COVID-19 (n=20). Students referenced several personal experiences working with this population as well as a strong empathy for the group’s plight. Persons of color, immigrants or refugees (n=8), and low socioeconomic or low-resource populations (n=6) were also discussed. However, 13 students listed generally vulnerable populations, consisting of the elderly, those with mental illness, existing comorbidities, veterans, those incarcerated, those with disabilities and their caregivers.

Theme 2: Attitudes and Awareness: What Are the Contributors and Causes of Health Disparities?

Students reported on potential causes and contributors for health disparities and how COVID-19 has impacted these factors. Two attitudes and awareness-based subthemes emerged: social determinants of health and racism

Social Determinants of Health

COVID-19 Guidelines. Eleven students recognized that not all people can abide by COVID-19 guidelines, as not everyone has luxury of social distancing, specifically those who experience housing inequity, high housing density, or homelessness. Other students mentioned that not everyone has the ability to buy new masks or work from home. Four students discussed how abiding by COVID-19 guidelines stressed disparities in health care access during the pandemic by reducing patient access to routine care.

Health Care Access. Many students discussed health care access as a SDOH. Some reported attempting to reconcile their personal role in how to handle health care access disparities and advocate for/educate patients. Nine discussed how COVID-19 highlighted how the broken parts of our health care system leave vulnerable patients behind, such as patients with language barriers, lack of technology, and chronic conditions. Student responses highlighted mixed feelings about the benefit of telehealth. The majority of students identified that, while telehealth may be helpful for some, it may exacerbate disparities in care for those with limited technology. Several students discussed causes and consequences of treatment delays. Four expressed fear that worsened health outcomes would arise due system issues, such as lack of health care capacity or delayed treatment while others identified patient avoidance of appointments due to fear of COVID-19 as causing treatment delays. Two students identified root causes of this vulnerability as systemic racism and cracks in the system. One student also described that vulnerable patients' post-hospitalization may not have resources to carry on their care when they return home. Another noted that the risk of COVID-19 infection in health care settings could delay treatment for chronically ill patients.

Housing. Fifteen respondents noted housing as a cause of health disparities. Of these, five emphasized that lack of housing makes following a treatment plan and COVID-19 guidelines difficult, and two respondents identified that racial housing segregation negatively impacts health. Five students discussed the impacts of COVID-19 on housing (eg, financial instability leading to fear of eviction/housing instability)—that lack of housing typically coincides with lack of technological resources needed for remote care, and where one lives can determine their ability to access to supplies (eg, medical products, food). Two students noted that as emergency departments filled to the brim and shelters were closing, homeless persons were put at increased risk for contracting and spreading the virus.

Employment and Finances. Fourteen respondents noted that vulnerable populations consistently work essential or high-risk jobs, cannot work from home, afford personal protective equipment, and/or take time off from work. Others noted that this is particularly concerning among undocumented workers who struggled financially prepandemic, for those with limited savings, or who lost jobs during the pandemic. Two students emphasized the exorbitant costs of health care and how financial instability impacts access to telehealth. Food insecurity was also a concern for a small number of students. Four stated that COVID-19 is creating food insecurity or exacerbating preexisting food insecurity, while one mentioned that vulnerable populations may be unable to order take-out food that more privileged groups may be able to afford during the pandemic.

Existing Chronic Conditions. Thirteen students reported chronic health conditions as causes of health disparities during COVID-19. Many students recognized that vulnerable populations have disproportionate rates of comorbidities, putting them at risk for higher COVID-19 morbidity and mortality and decreased access to health care. Additionally, five other students noted that patients who need in-person chronic health management may still need acute visits during the pandemic, subsequently increasing their risk of COVID-19 infection and increasing the burden on hospitals/providers.

Transportation. Seven students discussed the role of reliable, safe transportation. Students perceived that transportation hardships were exacerbated by COVID-19 and the development of an added layer stigma for those using public transit during COVID-19.

Racism. Although Black, indigenous, and persons of color (BIPOC) were common descriptors used when discussing those affected (n=13), only four students directly described racism as a cause of health disparities during COVID-19.

Theme 3: Action: What Needs to Be Done?

Students wrote about how COVID-19 impacted how they viewed their role in medicine and health care delivery. Four action-based subthemes emerged.

Health Care Reform. Students from both cohorts overwhelmingly commented on how COVID-19 reinforced their desire to effect change on health care reform, particularly after they saw how the pandemic affected vulnerable populations. Twelve respondents reflected on how the health disparities highlighted by COVID-19 fueled their desires to work with underserved populations as advocates and agents of change. Five respondents wrote about how this experience demonstrated how critical universal health care is in improving access to care and addressing social determinants. Five others wrote about improving assessment of health literacy, dissemination of information and education within the community, increasing access to care, and forming partnerships beyond hospital walls. Two respondents saw the use of applying quality improvement principles to make meaningful changes to systemic health inequity.

Use of Telehealth. Seventeen respondents thought telehealth and phone visits increased connections with patients during the pandemic. While acknowledging their limitations, students felt the flexibility of telehealth visits would allow more patients to be seen, particularly if they have barriers such as transportation, language, or fear of COVID-19 infection. Students expressed optimism about overcoming barriers, with one suggesting social workers with iPads could do outreach to increase care among vulnerable communities.

Three others posited that COVID-19 has demonstrated that telehealth is the way forward and can help providers impress upon patients the importance of preventive care. However, two students framed disparities in health care access as patient unwillingness or distrust in the system.

Being an Empathetic Provider. Students reported being personally moved by what they saw happening to their patients and communities. Several reported a newfound acknowledgement of their patients’ stressors and experiences as marginalized members of society and that they, as future physicians, need to be ready to care for them.

Community Health Intervention. Eight students wrote about the importance of public health and community interventions in improving health disparities. Four respondents felt that physicians have a responsibility to consider the socioeconomic, cultural, and educational backgrounds of patients in order to be effective clinicians and build strong relationships. One student acknowledged the limitations of some patients to follow current health recommendations during the pandemic and the need for educators to highlight ways for students to become more directly involved to impact social determinants of health.

The premise of our curricula is that with attention to specific needs of patients, we can improve care of vulnerable persons and communities. Students in our study clearly internalized these lessons and were highly critical of how the design of health care impacted their patients’ risks and challenges during COVID-19. Our goal was to capture how well students synthesized information they learned across their educational experiences to inform their approaches to becoming physicians. The data support our expectations that students could identify vulnerable populations during COVID-19, develop awareness of health inequity causes, and most importantly examine their personal, professional, and social responsibility in addressing disparities. This reinforces the BBCF’s premise that knowledge can impact attitudes and awareness and ignite a sense of responsibility. It is important for the field to monitor whether these experiences will translate into more distal changes of how students deliver care and advocate for systemic change.

According to Bloom’s Taxonomy of educational objectives, 12 students provided evidence of being able to remember, understand, apply, analyze, and evaluate how their educational curricula applied to their patients during COVID-19. Students identified a variety of at-risk populations and reported several SDOH. Students primarily focused on homeless persons and BIPOC as vulnerable populations, which our modules explicitly discuss. The focus on these two groups likely also reflected events occurring during data collection. Students’ reflections coincided with the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, social justice protests, and homeless encampment protests in Philadelphia throughout the summer of 2020. Essays demonstrated how students integrated the effects of SDOH, social justice principles, and COVID-19 guidelines, which highlighted sensitivity to intersectionality and a deeper understanding of systemic challenges. 13 Only a few students used direct language about racism, indicating that students may be uncomfortable, unfamiliar, or hesitant to directly name structural racism as the cause of disparities. Medical educators need to find ways to address this shortcoming, as proper labeling can yield social awareness and spark responsibility and action.

This study’s most significant strength is that the topic of vulnerable populations and health inequities in medical education has enduring implications, individually and societally. Knowledge of the who, what, and why aspects of health disparities is the precursor to addressing downstream action, tenets of foundational behavior change theory. It was evident that students felt they had an individual responsibility to address health inequities, but that they want support from health systems. 14 Many discussed that they wanted to be advocates but that overall health care and procedural reform is critical for making long-term changes. This finding denotes that our curriculum did make some impact on the level we intended: developing strong empathetic student-doctors to go into systems and make change. Counter to our expectations, only two students specifically recognized how quality improvement techniques can be part of their efforts to address health inequity in their own practices. Overall, students may be good at critiquing situations and determinants but struggle in fully applying an action-oriented approach to address the next steps in truly confronting these concerns. Students need more practice to complete guided QI projects that can help them see how to revise processes and strategies when conflicts or obstacles arise.

Limitations

Students were limited in their essay word count and were asked to write reflectively. Additionally, our clerkship students were predominately White and from a single medical institution, limiting generalizability.

Preparing the next generation of clinicians with the necessary skills to discuss health disparities, identify root causes, and search for creative solutions is paramount to health care reform. Using a reflective essay methodology allowed us to capture deep, robust information on student understanding of health disparities, and revealed education areas to further address, such as conscious language when describing racism and its implications. The COVID-19 pandemic may have facilitated this process by raising the receptivity of students to this curricula. As medical educators, we have a responsibility to teach students how to turn this awareness into action.

This work was funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of a Primary Care Medicine and Dentistry Clinician Educator Career Development Awards Program, Grant Number K02HP30821. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS, or the US Government.

References

1. Williams DR, Cooper LA. COVID-19 and health equity-a new kind of “herd immunity”. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2478-2480. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.8051

3. Okonkwo NE, Aguwa UT, Jang M. COVID-19 and the US response: accelerating health inequities. BMJ Evidence-Based Med. 2020. doi:10.1136/bmjebm-2020-111426

4. Castillo EG, Isom J, DeBonis KL, Jordan A, Braslow JT, Rohrbaugh R. Reconsidering systems-based practice: advancing structural competency, health equity, and social responsibility in graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2020;95(12):1817-1822. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003559

6. Glanz K, Rimer B, Viswanath K. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4th Ed. - PsycNET. 4th ed. (Glanz K, Rimer B, Viswanath K, eds.). Jossey-Bass; 2008. Accessed July 7, 2021. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2008-17146-000

8. Smith RS, Silverio A, Casola AR, Kelly EL, de la Cruz MS. Third-year medical students’ self-perceived knowledge about health disparities and community medicine. PRiMER Peer-Rev Rep Med Educ Res. 2021;5:9. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2021.235605

9. D de la Cruz MS, Smith RS, Silverio AE, Casola AR, Kelly EL. What we learned in the development of a third-year medical student curricular project. Perspect Med Educ. 2021;10(3):167-170. doi:10.1007/s40037-021-00648-x

10. Bassot B. The Reflective Journal: Capturing Your Learning for Personal and Professional Development. Palgrave Macmillian; 2013.

11. Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277-1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

13. Denizard-Thompson N, Palakshappa D, Vallevand A, et al. Association of a health equity curriculum with medical students’ knowledge of social determinants of health and confidence in working with underserved populations. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e210297. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0297

14. Sharma M, Pinto AD, Kumagai AK. Teaching the social determinants of health: a path to equity or a road to nowhere. Acad Med. 2018;93(1):25-30. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001689

There are no comments for this article.