Background and Objectives: Despite the requirements of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) to provide feedback, assessments are often not meeting the needs of resident learners. The objective of this study was to explore residents’ approach to reviewing, interpreting, and incorporating the feedback provided in written faculty assessments.

Methods: We conducted semistructured interviews with 14 family medicine residents. We used line-by-line iterative coding of the transcripts through the constant comparative method to identify themes and reach a consensus.

Results: The study revealed the following themes: (1) residents value the narrative portion of assessments over numerical ratings, (2) performance reflection and reaction are part of the feedback process, (3) residents had difficulty incorporating formal assessments as many did not provide actionable feedback.

Conclusions: Residents reported that narrative feedback gives more insight to performance and leads to actionable changes in behaviors. Programs should consider education for both faculty and residents on the usefulness, importance, and purpose of the ACGME Milestones in order to accurately determine resident competency and provide a summative assessment. Until the purpose of the ACGME Milestones is realized and utilized, it should be noted that the comment portion of evaluations will likely be the focus of the resident’s interaction with their assessments.

Resident feedback is critical for improvement and excellent performance, yet residents report that they infrequently get it.1-3 The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires faculty to directly observe, evaluate, and provide feedback on resident performance during each rotation.4 Residents can use this ongoing, formative feedback to improve their learning in the context of provision of patient care or other educational opportunities.4 Feedback can also be summative in that faculty evaluate a resident’s learning by comparing residents against the objectives, goals, and standards stated by the program. Additionally, formal assessments/evaluations are utilized for advancement and resident promotion.4 To accomplish both summative and formative feedback, faculty assess resident performance on multiple facets using numerical milestones.4 Typically, the assessment forms also include a comment portion for narrative feedback that may include feedback on specific patient encounters, corrective information, and alternative strategies. Effective assessments with milestones are crucial to residency training for ongoing development of individual learners and continual quality improvement of training programs.2- 8

Faculty report multiple barriers to providing residents with meaningful feedback, including time constraints, the often-brief duration of relationship between preceptor and trainees, inconsistencies among evaluations, quantity of evaluations, lack of training for faculty, and typical concerns of how certain statements may affect resident progression.9, 10 Trainees also perceive that assessors become preoccupied with form completion and box checking as opposed to providing meaningful advice. Residents find greater value from feedback derived from natural conversations compared to interpreting numbers from a checklist questionnaire.11 Yet, clinical competency committees use both narrative and numeric assessments for promotion decisions.2, 12 Thus, there may be fear from residents that any suboptimal performance on a single assessment may lead to remediation or impact their career prospects, causing residents to avoid actively seeking feedback or remain disengaged with the evaluative process.11 Evidence exists regarding residents’ attitudes toward written assessments, including concerns for quantity over quality, lack of understanding on how to utilize feedback, and adversity to criticism, but little is known about the actual process that residents use when reviewing their assessments. 1, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11

The objective of our study was to understand residents’ approach to reviewing, interpreting, and incorporating the feedback provided in faculty assessments. Our study explored what residents reflect on prior to viewing their evaluations, the procedures they followed when reviewing them, the value they placed on the numerical milestone scales, and the emphasis they put on written feedback.

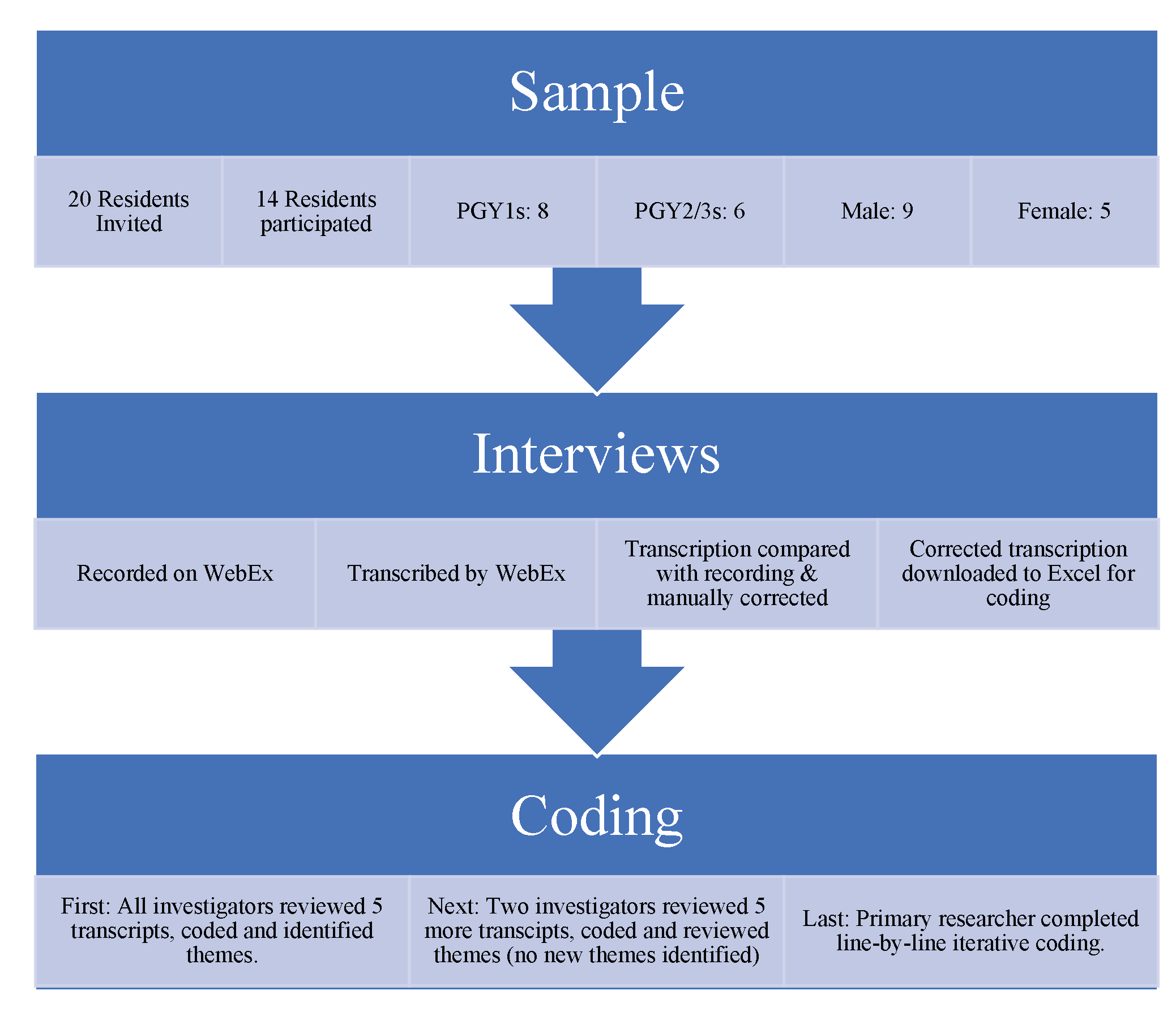

Utilizing an interview-based constructivist grounded-theory approach, this qualitative study explored how residents interact with their assessments. 13 The interviews were conducted with a target population of residents in an ACGME-accredited family medicine residency program. Fourteen of the 20 eligible residents voluntarily participated. The interviews followed a semistructured guide (Table 1) intended to elicit evidence on residents’ practice, attitudes, and knowledge of the assessment process. The interview guide, created through a collaboration (T.H., B.F.), was piloted with a resident (coauthor O.B.) and slightly revised for clarity. Interviews were conducted by the primary author (B.F.) in order to preserve confidentiality from the faculty who may be involved in resident training. All interviews were conducted via WebEx in January of 2021. Following the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research and data analysis 14 and consistent with the tenets of constructivist grounded-theory methodology, 15 we began with independent data analysis and initial coding of five transcripts. This provided the foundation for a coding meeting where examples of themes were discussed and agreed upon through consensus. Two researchers (B.F., O.B.) then analyzed an additional five transcripts; common themes were discussed at the following coding meeting of the entire team. B.F. coded the final four transcripts, and O.B. reviewed them. We conducted a final coding meeting to finalize themes through consensus and discussion (Figure 1). The Central Michigan University Institutional Review Board determined the study to be exempt.

|

Process

|

|

1. Interview questions were developed as a collaboration between the primary investigator (T.H.) and the primary researcher (B.F.).

|

|

2. The questions were pilot tested with two residents and refined in collaboration with the pilot-test subjects.

|

|

3. Residents were invited to participate via email with a link to select their own appointment time via an online booking service (YouCanBookMe.org).

|

|

4. Semistructured interviews were conducted by the primary researcher (B.F.) and recorded via WebEx.

|

|

5. Some residents shared their screen to discuss a particular evaluation, some residents opened an evaluation to discuss but did not share their screen, and some residents spoke of their process from memory.

|

|

Interview Guide: Questions Asked During the Interviews

|

|

1. Before you look at it, describe what goes through your mind when you initially get your end-of-rotation evaluation.

|

|

2. Walk me through the process of opening your evaluation. What do you focus on first when checking your end-of-rotation evaluations? Second? After that?

|

|

3. How would you compare the usefulness of the numerical versus the narrative portion of the evaluation?

|

|

|

Follow-Up Probes: What parts of this evaluation form do you find the most helpful? What parts of the evaluation do you find least helpful? What do you take away from the numerical portion of the evaluation? What do you take away from the comment portion of the evaluation?

|

|

4. How do you feel the evaluation process could be changed?

|

|

5. How could evaluation forms themselves be changed to support this process?

|

Our study revealed most residents (71%) viewed the comment section first, and all but two residents (85%) viewed the comment section as the most important part of the assessment (Appendix Table A). The study outcomes revealed themes focused on the assessments, the assessed, and the assessor.

Theme 1: Residents Value the Narrative Portion of Assessments

As a process, most residents opened their evaluations, scrolled past the numerical data, and looked at the comments. As a focus, residents tended to scrutinize the narrative on the evaluation first, and most considered the comments more useful than the numerical portion of the evaluation, whether they viewed that section first or last. As for value, residents appreciated feedback in the comments when it was timely, constructive, and consistent across evaluations (Appendix Table A).

Theme 2: Performance Reflection and Reactions are Part of the Feedback Process

As residents opened their evaluations, many reported that they took the opportunity to reflect on their performance, yet some reported anxiety when thinking about what the faculty thought of their performances. The reflections included wondering if their actions were interpreted differently by faculty than the resident remembered, and reactions to faculty perceptions that included nervousness, anxiety, and even fear (Appendix Table A).

Theme 3: Residents Had Difficulty Incorporating Formal Assessments as Many Did Not Provide Actionable Feedback

Overall, residents reported that formal assessments did not provide tangible and timely feedback that was meaningful. Residents reported frustration with evaluations that were not available immediately. The residents described feedback given only at the end of a rotation as “having no value,” especially when they did not have another similar rotation soon so they could act on this information. Therefore, they expressed a desire for midrotation assessments to allow them time to immediately correct their practice. Recall bias for both residents and faculty were reported as well; with too much time passing between the interactions and the assessment, residents would forget when the observed clinical interactions occurred or the interactions therein. Residents expressed concerns with imprecise feedback due to faculty forgetting the resident interactions and performances between the time the actions occurred and the time when faculty completed their assessment. Residents in this study also expressed concern about inconsistencies among evaluators, including issues with the feedback provided when the duration of the interaction was short or there was no direct observation of the resident’s clinical performance. Residents disregarded evaluations containing number straight-lining (choosing the same number throughout the assessment) since this indicated the faculty’s lack of mindful assessment of their performance (Appendix Table A).

The intention of the ACGME assessment system is both formative and summative assessment4 and this study determined how residents engage with this evaluation system. The residents in our study reported that narrative feedback, more than numeric ratings, gave more insight to performance and led to actionable changes in behaviors. Comments provide constructive feedback and informed self-assessment, and they detail information for program leadership on resident performance.3, 16

This study supported the importance of faculty building rapport with residents as an important part of the evaluation process.17 Similar to prior studies, residents discount faculty evaluations when they perceive lack of engagement and find value in feedback from faculty that have observed their skills on multiple occasions.9, 16, 18, 19

Residents noted that self-reflection is critical to the evaluation process. This is supported by the R2C2 model (relationships, reactions, content, coaching) where the “reactions” phase encourages residents to reflect on and compare their view of their performance against the feedback received from faculty. 17 Recognizing that residents are reflective while reviewing their evaluations is important to understanding how residents engage in feedback. Residency programs should facilitate growth of informed self-assessment skills during training since independent physicians must identify their own knowledge and skill gaps to continue professional growth and enhance patient care.17, 20 The residents in our study also reported that time between performance and feedback can lead to discrepancies between the faculty members’ and residents’ memory of patient encounters, thus delaying implementation of practice change and impairing growth. Residents desire real-time feedback when content, context, and perceptions are available for immediate recall.21

This study has several limitations, including sample size (the subjects may not represent all residents), and generalizability (the study involved a single site and specialty). The ACGME Milestones are designed to personalize the competency of each resident on their journey toward the independent practice of medicine. 4 Future studies should focus on response time for feedback and teaching approaches to incorporating feedback. Programs should educate faculty on how to provide meaningful and actionable feedback to improve the usefulness of the ACGME Milestones.16 Residency programs should also understand that the milestones were designed to facilitate specialty goals and curriculum improvement for guiding residents.2

In conclusion, a program’s approach to formative and summative assessments should include quality, useful data. Until these changes are implemented, the comment portion of evaluations will likely remain the focus of residents’ interaction with their assessments. Faculty should therefore engage residents in the feedback process and reinforce areas of strength while also providing constructive criticism supported by specific examples within the narratives and suggestions for improvement.3, 18, 4

References

-

Sender Liberman A, Liberman M, Steinert Y, McLeod P, Meterissian S. Surgery residents and attending surgeons have different perceptions of feedback. Med Teach

. 2005;27(5):470-472. doi:10.1080/0142590500129183

-

Holmboe ES, Yamazaki K, Nasca TJ, Hamstra SJ. Using longitudinal milestones data and learning analytics to facilitate the professional development of residents: early lessons from three specialties. Acad Med

. 2020;95(1):97-103. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002899

-

Raaum SE, Lappe K, Colbert-Getz JM, Milne CK. Milestone implementation’s impact on narrative comments and perception of feedback for internal medicine residents: a mixed methods study. J Gen Intern Med

. 2019;34(6):929-935. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-04946-3

-

-

-

-

Govaerts M, van der Vleuten CP. Validity in work-based assessment: expanding our horizons. Med Educ

. 2013;47(12):1164-1174. doi:10.1111/medu.12289

-

Ramani S, Post SE, Könings K, Mann K, Katz JT, van der Vleuten C. It’s just not the culture”: A qualitative study exploring residents’ perceptions of the impact of institutional culture on feedback. Teach Learn Med

. 2017;29(2):153-161. doi:10.1080/10401334.2016.1244014

-

Albano S, Quadri SA, Farooqui M, et al. Resident perspective on feedback and barriers for use as an educational tool. Cureus

. 2019;11(5):e4633. doi:10.7759/cureus.4633

-

Holmboe ES, Ward DS, Reznick RK, et al. Faculty development in assessment: the missing link in competency-based medical education. Acad Med

. 2011;86(4):460-467. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820cb2a7

-

Branfield Day L, Miles A, Ginsburg S, Melvin L. Resident perceptions of assessment and feedback in competency-based medical education: a focus group study of one internal medicine residency program. Acad Med

. 2020;95(11):1712-1717. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003315

-

Hauer KE, Chesluk B, Iobst W, et al. Reviewing residents’ competence: a qualitative study of the role of clinical competency committees in performance assessment. Acad Med

. 2015;90(8):1084-1092. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000736

- Creswell JW, Creswell JD. Research Design: Qualitative. Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; 2018.

-

O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med

. 2014;89(9):1245-1251. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388

-

-

Sargeant J, Eva KW, Armson H, et al. Features of assessment learners use to make informed self-assessments of clinical performance. Med Educ

. 2011;45(6):636-647. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03888.x

-

Sargeant J, Lockyer J, Mann K, et al. Facilitated reflective performance feedback: developing an evidence-and theory-based model that builds relationship, explores reactions and content, and coaches for performance change (R2C2). Acad Med

. 2015;90(12):1698-1706. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000809

-

Molloy E, Ajjawi R, Bearman M, Noble C, Rudland J, Ryan A. Challenging feedback myths: Values, learner involvement and promoting effects beyond the immediate task. Med Educ

. 2020;54(1):33-39. doi:10.1111/medu.13802

-

Bakke BM, Sheu L, Hauer KE. Fostering a feedback mindset: a qualitative exploration of medical students’ feedback experiences with longitudinal coaches. Acad Med

. 2020;95(7):1057-1065. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003012

-

Schultz K, McGregor T, Pincock R, Nichols K, Jain S, Pariag J. Discrepancies between preceptor and resident performance assessment: using an electronic formative assessment tool to improve residents’ self-assessment skills. Acad Med

. 2022;97(5):669-673. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004154

-

Fredette J, Michalec B, Billet A, et al. A qualitative assessment of emergency medicine residents’ receptivity to feedback. AEM Educ Train

. 2021;5(4):e10658. doi:10.1002/aet2.10658

There are no comments for this article.