Background and Objectives: Despite the significant effects of homelessness on health, medical and health professions students rarely receive formal education in caring for individuals experiencing homelessness. We describe the implementation and evaluation of a novel student-run Patient Navigator Program (PNP) and its prerequisite elective that trains students in patient navigation principles specific to homelessness in the local community.

Methods: We analyzed pre- and postsurvey matched responses from students immediately before and after course completion. The survey utilizes the externally-validated instruments Health Professional Attitudes Toward the Homeless Inventory (HPATHI) and the Student-Run Free Clinic Project (SRFCP) survey. We examined differences using paired t tests and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Students also completed separate end-of-curriculum evaluation forms assessing satisfaction with the course.

Results: After completing the elective, students (n=45) demonstrated improvement in self-assessed attitude towards individuals experiencing homelessness (P=.03), specifically an increase in reported social advocacy (P<.001); and an increase in self-perceived knowledge about (P<.001), efficacy in working with (P=.01), and skills in caring for (P<.001) underserved groups. The elective also received high student satisfaction ratings.

Conclusions: Formal education in patient navigation and caring for individuals experiencing homelessness improves self-assessed preparedness of future health care providers in serving homeless and underserved populations.

Despite the significant impact of homelessness on health,1-4 most medical and health professions students receive no formal education in caring for homeless populations.5-7 Patient navigators, who work directly with patients to overcome health barriers, have been shown to provide substantial benefit to underserved and homeless populations, including reduction in health disparities and all-cause mortality.8, 9 Medical students rely primarily on free clinic volunteering to learn about homeless healthcare, which has been shown to supplement medical education by improving student attitude and knowledge in working with people experiencing homelessness.10, 11 We sought to build upon these principles by coupling a unique volunteering opportunity with formal education in patient navigation specific to the local homeless community.

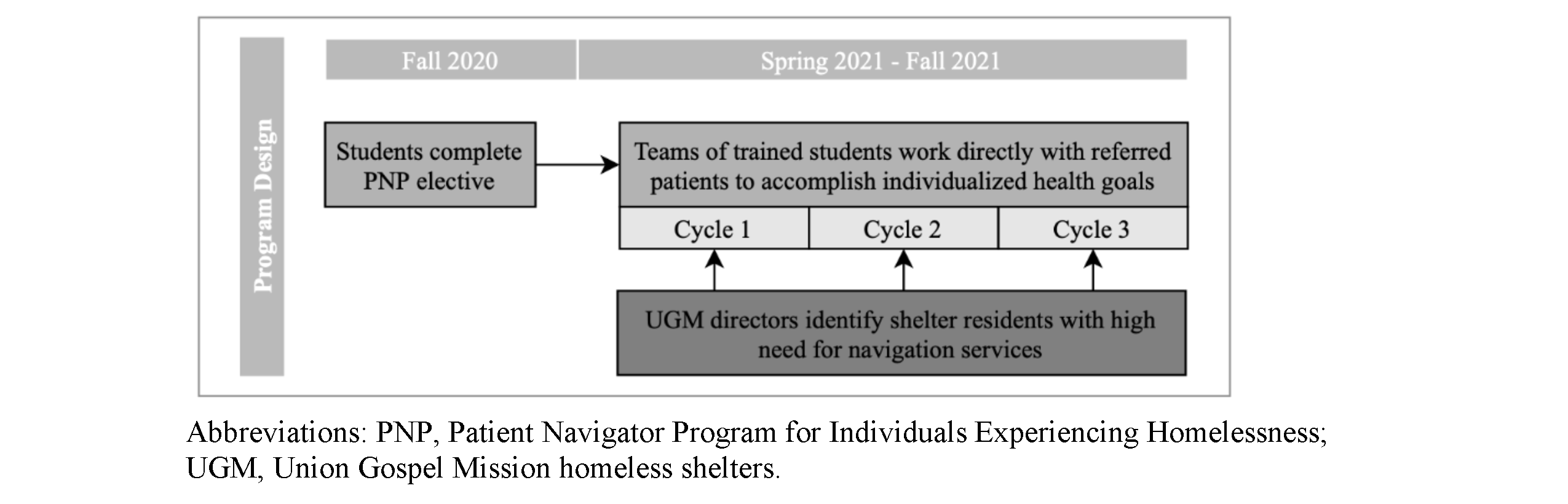

The Patient Navigator Program (PNP) for Individuals Experiencing Homelessness and its prerequisite training elective were developed by students at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (UTSW) in partnership with the UTSW Department of Family and Community Medicine and Union Gospel Mission (UGM) homeless shelters. The program connects residents of the homeless shelters with student navigators trained in patient-centered problem solving, the identification of local resources, and addressing barriers faced by individuals experiencing homelessness (Figure 1). Beyond generating a capable cohort of patient navigators serving the community, our goal in implementing the elective is to improve the capability of future health care providers in serving homeless and underserved populations throughout their careers.

Curriculum design was informed by a review of homeless health and patient navigator program curricula,11-15 individualized to PNP with recommendations from UGM leaders and UTSW faculty. The PNP elective is an optional course available to medical and health professions students in any year of study, though it is primarily designed for preclerkship students without clinical experience. Students who complete the course are given the option to serve as a navigator for 1 year, starting the following semester. The course consists of seven 2-hour sessions throughout 1 semester, each session composed of one hour of didactics and 1-hour of program-specific training. Didactics are led by community experts, including health care providers, social workers, community outreach workers, and directors of homeless organizations; program-specific training was taught the first year by PNP student leaders who actively assisted in program development, and will be taught in following years by active student navigators (Table 1).

|

Session

|

Topic

|

Core Competencies

|

|

1

|

A conversation with an individual experiencing homelessness

|

Discuss health care barriers faced by homeless populations

|

|

Conversation with an individual living at the UGM shelter experiencing chronic homelessness

|

|

An introduction to PNP

|

Define the role of a patient navigator

|

|

Discuss the relevance of patient navigation for individuals experiencing homelessness in DFW

|

|

2

|

Social determinants of health (SDOH) in homeless populations

|

Discuss how health inequities are generated through CDC’s SDOH place-based framework

|

|

Learn to actively recognize and assess the ways that SDOH may be impacting your patient's health outcomes

|

|

Health literacy

|

Define the key concepts of health literacy

|

|

Apply the teach-back technique to increase clear communication and patient understanding

|

|

In-class activity: Practice scenarios in small groups via Zoom break-out sessions (how to write SMART goals, how to apply the teach-back method)

|

|

3

|

Common barriers and resources in DFW

|

Prior to session: Submit a reflection on barriers that someone might face when going to their physician’s office—what factors make keeping appointments less or more challenging?

|

|

Understand the common barriers faced by individuals experiencing homelessness in DFW

|

|

Become familiar with the most-utilized resources available to the homeless population in DFW

|

|

Describe the services that these organizations can provide and how a client may access these services

|

|

PNP database and navigator resources

|

Learn how to access and use the PNP-specific resources database

|

|

In-class activity: Practice searching for applicable resources and applying problem-solving skills in addressing specific barriers

|

|

4

|

Professional boundaries, client communication, cultural sensitivity

|

Prior to session: Submit a short essay reflecting on a time you have experienced or witnessed bias, prejudice, or discrimination

|

|

Identify sociocultural factors that have contributed to the marginalization of the homeless community

|

|

Identify effective communication strategies for establishing trust and rapport with homeless clients

|

|

Describe the concept of shared decision making and how to apply this practice as a patient navigator

|

|

PNP workflow: Client encounters

|

Discuss the importance of client confidentiality and adherence to PNP safety guidelines

|

|

Apply understanding of SMART goal-setting to practice scenarios with classmates

|

|

Understand PNP workflow and timelines

|

|

5

|

Introduction to motivational interviewing

|

Describe the importance of patient-centered care aimed at behavior change

|

|

Describe the mindset and approach of MI

|

|

Recall the tools used in the OARS model of MI: open questions, affirmation, reflective listening, and summarizing discussions

|

|

In-class activity: Practice scenarios in small groups via Zoom break-out sessions (MI)

|

|

6

|

Student group presentations

|

Prior to session: Groups have 3 weeks to complete a 1-hour interview with an assigned community partner on one of the following topics. You will use this interview and further research to create a presentation with handouts for your classmates

|

|

Topics: Homelessness among veterans, COVID-19 response in local shelters, trauma-informed care, high-priority clinical issues

|

|

7

|

Reflection and discussion

|

Understand compassion fatigue, recognize signs of burnout and secondary traumatic stress

|

|

Identify strategies for self-care and stress management

|

|

In-class activity: Write a letter to your future self in 1 year—why do you want to work with individuals experiencing homelessness, and what do you hope to have learned as a navigator?

|

Data Collection and Analysis

Students planning to serve as navigators were required to complete an anonymous linked RedCap survey delivered via email at two separate time points: prior to the first session, and immediately following the final session. The survey consisted of demographic questions, questions assessing career goals, and two externally-validated instruments: Health Professionals’ Attitudes Toward the Homeless Inventory (HPATHI)16 and the Student-Run Free Clinic Project (SRFCP) survey.17 This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at UTSW.

Statistical Analysis

Paired t tests and Wilcoxon rank sign tests assessed statistical significance differences of pre- and postcourse results. Statistical tests were two-sided, and a P value of <.05 and was considered significant. We performed all analyses using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 24.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

All students enrolled in the course also completed required anonymous UTSW-administered end-of-curriculum evaluation forms through RedCap software, delivered via email, consisting of nine core Likert-scale questions to assess course objectives, content, organization, and clinical relevance. The second half of the form, which was optional, consists of 12 open-ended questions evaluating student satisfaction.

Two authors reviewed responses to open-ended questions and independently identified themes through an open-coding approach. They then approached consensus regarding thematic categories and representative quotes, used to supplement and contextualize quantitative data.

Student Characteristics

Characteristics of student participants are highlighted in Table 2 and Table 3. Fifty-six students enrolled in the elective during its pilot implementation in fall 2020, with 46 students choosing to serve as a student navigator for 1 year following course completion. Of these students, 46 completed the presurvey and 45 completed the postsurvey. In the presurvey, a large proportion of students reported interest in working with individuals experiencing homelessness (25, 54.4%), low-income individuals (35, 76.1%), and racial/ethnic minorities (37, 80.4%). However, 52.2% (24) reported less than 1 month of experience working with or volunteering directly among individuals experiencing homelessness.

|

Demographics (N=46)

|

|

|

n (%)

|

|

Age (Years)

|

|

<21

|

5 (10.9)

|

|

22-25

|

37 (80.4)

|

|

26-29

|

3 (6.5)

|

|

>30

|

1 (2.2)

|

|

Gender

|

|

Cisgender woman

|

35 (76.1)

|

|

Cisgender man

|

11 (23.9)

|

|

Race/Ethnicity*

|

|

Non-Hispanic White

|

22 (47.8)

|

|

Hispanic, Latino, Spanish origin

|

5 (10.9)

|

|

Asian

|

20 (43.5)

|

|

Middle Eastern or North African

|

2 (4.4)

|

|

Black/African American

|

1 (2.2)

|

|

Average Family Income

|

|

$20,000 or less

|

2 (4.4)

|

|

$20,001 to $30,000

|

3 (6.5)

|

|

$30,001 to $40,000

|

1 (2.2)

|

|

$40,001 to $50,000

|

2 (4.4)

|

|

$50,001 to $60,000

|

1 (2.2)

|

|

$60,001 to $70,000

|

1 (2.2)

|

|

$70,001 to $80,000

|

1 (2.2)

|

|

$80,001 to $90,000

|

2 (4.4)

|

|

$90,001 to $100,000

|

3 (6.5)

|

|

$100,001 or more

|

26 (56.5)

|

|

Do not know

|

3 (6.5%)

|

|

Prefer not to answer

|

1 (2.2%)

|

|

Personal Experience of Homelessness

|

|

Yes

|

3 (6.5)

|

|

No

|

43 (93.5)

|

|

Prior Experience Working With Individuals Experiencing Homelessness

|

|

None

|

14 (30.4)

|

|

Less than 1 month

|

10 (21.7)

|

|

1 month to 6 months

|

4 (8.7)

|

|

6 months to 1 year

|

7 (15.2)

|

|

1 year to 3 years

|

9 (19.6)

|

|

More than 3 years

|

2 (4.4)

|

|

Interests (N=46)

|

|

I particularly want to work with:

|

Strongly Disagree

|

Disagree

|

Uncertain

|

Agree

|

Strongly Agree

|

|

Low-income individuals

|

0 (0)

|

1 (2.2)

|

10 (21.7)

|

21 (45.7)

|

14 (30.4)

|

|

Racial/ethnic minorities

|

0 (0)

|

1 (2.2)

|

8 (17.4)

|

18 (39.1)

|

19 (41.3)

|

|

Individuals experiencing homelessness

|

0 (0)

|

2 (4.3)

|

19 (41.3)

|

20 (43.5)

|

5 (10.9)

|

|

Individuals with severe mental illness

|

1 (2.2)

|

6 (13.0)

|

27 (58.7)

|

10 (21.7)

|

2 (4.3)

|

|

Elderly patients

|

0 (0)

|

13 (28.3)

|

18 (39.1)

|

12 (26.1)

|

3 (6.5)

|

Survey Results

Pre- and postsurvey scores of self-assessed attitudes, skills, knowledge, and efficacy are shown in Table 4. Students who participated in the elective demonstrated an increase in self-assessed social advocacy (P<.001) and total HPATHI score (P=.03), indicating an overall improvement in self-perceived attitude toward individuals experiencing homelessness. Per SRFCP survey results, students also demonstrated an increase in self-perceived knowledge about underserved groups (P<.001), and self-efficacy in caring for underserved groups (P=.01). The largest overall score increase was reported in self-perceived skills in caring for the underserved, with an average Likert score average of 2.86 preelective and 4.17 postelective (P<.001).

|

Instrument

|

Subscale

|

Pretest Average

|

Posttest Average

|

Mean Change

|

P Value

|

|

HPATHI

|

Personal advocacy

|

3.97

|

3.99

|

+0.02

|

.46

|

|

Social advocacy

|

4.25

|

4.44

|

+0.19

|

<.001

|

|

Cynicism

|

2.74

|

2.76

|

+0.01

|

.73

|

|

Total

|

3.9

|

3.97

|

+0.07

|

.03

|

|

SRFCP

|

Attitudes

|

6.28

|

6.35

|

+0.07

|

.66

|

|

Skills

|

2.86

|

4.17

|

+1.31

|

<.001

|

|

Knowledge

|

3.43

|

4.53

|

+1.1

|

<.001

|

|

Self-efficacy

|

4.73

|

5.37

|

+0.64

|

.01

|

Student Satisfaction

Review of anonymous student feedback through the end-of-curriculum evaluation forms (56) indicated high student satisfaction, with 94.6% (53) agreeing that they would recommend the elective to future students. Of these 56 students, 27 elected to answer the optional open-ended questions, with responses summarized in Table 5.

|

Category

|

Representative Quotes

|

|

Exposure to patient perspective and the experience of homelessness

|

“I really enjoyed hearing from the woman experiencing homelessness [...] She was very open and honest with us about her experiences and I learned a lot from her. Having that as our first session really made me interested in continuing to come back to the elective.”"This is the first time I've been able to hear the perspective of a patient experiencing homelessness and I think that is invaluable."

|

|

Connecting with community organizations and local resources

|

“It was incredible being able to interview who we did. I don't think I will ever have an opportunity like that again."“If it wasn't for this course, I don't see how I would have learned about some of the services in the Dallas area.”

|

|

Role models

|

“This was an eye-opening course, I loved it and would recommend it to everyone. I enjoyed the guest speakers, I think that was the best part.”“I loved hearing how passionate people were for the work they do. It was really helpful to hear specific experiences and stories, which are more memorable and more multifaceted than just hearing generalizations about homeless populations.""Amazing and inspirational presentation. [...] stories and insights were incredibly moving and provided tangible examples of what barriers to care and challenges are faced by many individuals experiencing homelessness."

|

|

Curriculum format

|

"The hardest thing to me about this course was the timing - a two hour zoom [sic] lecture in the evening was pretty tough to sit through and stay engaged in. I think I might have felt differently if it were in person, but over zoom [sic] the two-hour biweekly format was really draining.”

|

Students who participated in this novel elective demonstrated significant improvements in self-assessed attitude toward homeless populations; they also reported increased self-perceived knowledge about, efficacy in treating, and skills in caring for underserved populations. The increase in reported social advocacy indicates an increase in student belief regarding society’s responsibility in caring for the homeless, likely due to curricular emphasis on systemic barriers to care. Of note, the largest score increase was seen in self-perceived skills in caring for underserved groups, which we believe can be attributed to the elective’s focus on motivational interviewing, helping patients set actionable goals, establishing professional boundaries, and practicing cultural sensitivity.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the study relied on students’ self-assessment of their attitudes and abilities, which is subject to cognitive bias. Additionally, the course was implemented at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, requiring adaptation to a virtual format, possibly affecting curriculum efficacy. Finally, we collected data immediately before and after completion of the elective; therefore, the long-term effect of this training on students’ perception of their future attitudes and skills is not known. Future studies will include survey administration at a third time point to assess if this improvement remains consistent throughout the year of PNP service that follows the course.

Next steps will focus on continuous program monitoring and improvement. We aim to increase student satisfaction in elective format, and are preparing to transition to in-person didactic and service learning. Throughout the year, we plan to optimize elective objectives by seeking feedback from our inaugural cohort of navigators, the clients they serve, and the leaders at UGM. This study suggests that formal education through competency-based lectures, emphasizing patient navigation principles specific to the local homeless community, is effective in increasing self-perceived preparedness to serve both as patient navigators and future health care providers to homeless and underserved populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of the UGM leaders, specifically those of Bruce Butler, CEO, and Patrice Denning, Women’s Program Director. They thank the students who contributed to curriculum design: Pooja Mallipaddi, Rachel Kim, Helena Zhang, Min Hyung (Arlene) Lee, and Jawaher Azam. Finally, they thank the students on the PNP Founding Team who were integral in design and implementation: Umaru Barrie, Thanos Rossopoulos, Nico Campalans, Alison Liu, Ashlyn Lafferty, Brayden Seal, and Claire Abijay.

Author Contributions. Authors A.L., N.B., T.R., U.B., P.P., P.D., and N.G. oversaw study conceptualization, methodology, investigation, and data curation. A.L. and A.S. oversaw project administration. A.L. and A.K. extracted the data and performed the statistical analyses. A.L., A.S., J.L. contributed to the interpretation of the results. A.L., A.S., J.L., A.K., D.M., G.R., H.L., and C.G. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. P.P., P.D., and N.G. supervised the project. All authors reviewed, provided feedback for, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Financial Support. Financial support for program implementation was awarded by Albert Schweitzer Fellowship and Texas Medical Association Foundation (TMAF).

Presentation: This study was presented at the 18th Annual Meeting of the Learning Communities Institute (virtual) in October 2021.

References

1. Tweed EJ, Thomson RM, Lewer D, et al. Health of people experiencing co-occurring homelessness, imprisonment, substance use, sex work and/or severe mental illness in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2021;75(10):1010-1018. doi:10.1136/jech-2020-215975

3. Lam JA, Rosenheck R. Social support and service use among homeless persons with serious mental illness. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1999;45(1):13-28. doi:10.1177/002076409904500103

4. DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2004;23(2):207-218. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207

5. Wear D, Kuczewski MG. Perspective: medical students’ perceptions of the poor: what impact can medical education have? Acad Med. 2008;83(7):639-645. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181782d67

6. Awosogba T, Betancourt JR, Conyers FG, et al. Prioritizing health disparities in medical education to improve care. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1287(1):17-30. doi:10.1111/nyas.12117

7. Asgary R, Naderi R, Gaughran M, Sckell B. A collaborative clinical and population-based curriculum for medical students to address primary care needs of the homeless in New York City shelters : teaching homeless healthcare to medical students. Perspect Med Educ. 2016;5(3):154-162. doi:10.1007/s40037-016-0270-8

8. Freeman HP, Rodriguez RL. History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer. 2011;117(15)(suppl):3539-3542.

9. Sarango M, de Groot A, Hirschi M, Umeh CA, Rajabiun S. The role of patient navigators in building a medical home for multiply diagnosed HIV-positive homeless populations. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2017;23(3):276-282. doi:10.1097/PHH.0000000000000512

10. Mercadante SF, Goldberg LA, Divakaruni VL, Erwin R, Savoy M, O’Gurek D. Impact of student-run clinics on students’ attitudes toward people experiencing homelessness. PRiMER Peer-Rev Rep Med Educ Res. 2021;5:19. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2021.489756

11. Meah YS, Smith EL, Thomas DC. Student-run health clinic: novel arena to educate medical students on systems-based practice. Mt Sinai J Med. 2009;76(4):344-356. doi:10.1002/msj.20128

12. Hashmi SS, Saad A, Leps C, et al. A student-led curriculum framework for homeless and vulnerably housed populations. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):232. doi:10.1186/s12909-020-02143-z

13. Calhoun EA, Whitley EM, Esparza A, et al. A national patient navigator training program. Health Promot Pract. 2010;11(2):205-215. doi:10.1177/1524839908323521

14. Nguyen TU, Tran JH, Kagawa-Singer M, Foo MA. A qualitative assessment of community-based breast health navigation services for Southeast Asian women in Southern California: recommendations for developing a navigator training curriculum. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(1):87-93. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.176743

15. Ustjanauskas AE, Bredice M, Nuhaily S, Kath L, Wells KJ. Training in patient navigation: A review of the research literature. Health Promot Pract. 2016;17(3):373-381. doi:10.1177/1524839915616362

16. Buck DS, Monteiro FM, Kneuper S, et al. Design and validation of the Health Professionals’ Attitudes Toward the Homeless Inventory (HPATHI). BMC Med Educ. 2005;5(1):2. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-5-2

17. Smith SD, Yoon R, Johnson ML, Natarajan L, Beck E. The effect of involvement in a student-run free clinic project on attitudes toward the underserved and interest in primary care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014;25(2):877-889. doi:10.1353/hpu.2014.0083

There are no comments for this article.