Background and Objectives: Mentorship is critical to physician recruitment, career development, and retention. Many underrepresented in medicine (URiM) physicians experience minority taxes that can undermine their professional objectives. Use of cross-cultural mentoring skills to navigate differences between non-URiM and URiM physicians can make mentorship relationships with URiM physicians more effective. This survey examined military family physician demographics and mentorship practices.

Methods: Design and Setting: Cross-sectional study using voluntary, anonymous data from the 2021 Uniformed Services Academy of Family Physicians (USAFP) Annual Meeting Omnibus Survey. Study Population: USAFP Members attending 2021 Virtual Annual Meeting. Intervention: None. Statistical analysis: Descriptive statistics and χ2 tests.

Results: The response rate to the omnibus survey was 52.9%, n=258. More than half of respondents did not have a URiM mentee and had not collaborated with a URiM colleague on a scholarly activity within the last 3 years. Only 54.7% of respondents could recognize and address minority taxes. URiM physicians were more likely to have a URiM mentee (65.4% vs 44.4%, P=.042) and to recognize and address minority taxes (84.6% vs 51.3%, P=.001). They also were more confident (84.6% vs 60.3%, P=.015) and more skilled in discussing racism (80.8% vs 58.2%, P=.026).

Conclusions: Structured programs are needed to improve knowledge and skills to support cross-cultural mentorship. Additional studies are needed to further evaluate and identify implementation strategies.

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), approximately 11% of US physicians are from minority groups that collectively represent 31% of the US population. 1, 2 Underrepresented in medicine (URiM) are those racial/ethnic groups that are underrepresented relative to their numbers in the US population. Groups identified as URiM include Black/African American, Hispanic, Native American (ie, American Indian, Alaskan, Hawaiian), and mainland Puerto Rican. Among academic medicine faculty, approximately 7% to 8% are physicians from URiM groups, and further disparities exist in leadership positions in medicine. 3-8

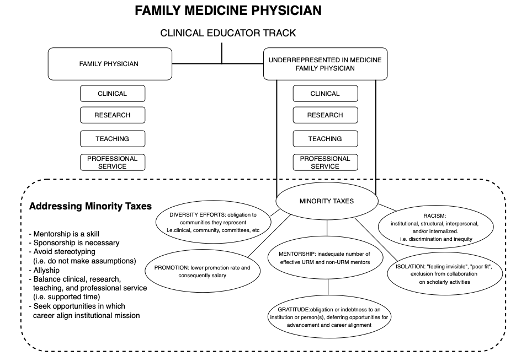

Mentorship is critical to physician recruitment, career development, and retention. 9 A mentor advises, supports, and shares knowledge through a longitudinal relationship with a mentee. 9-12 Unfortunately, many URiM physicians experience minority taxes that can adversely impact their career. 13, 14 Minority taxes are burdensome extra duties, experiences, or responsibilities unfairly assigned to physicians from minoritized groups (Figure 1). 13, 14 Use of cross-cultural mentoring skills to navigate differences between non-URiM and URiM physicians can make mentorship relationships with URiM physicians more effective. 15, 16

Our study had three objectives. The first was to obtain information on current demographics, URiM physician collaboration, and academic promotion among US military family physicians. The second was to assess their confidence and skills in discussing structural, systemic, and/or interpersonal racism in cross-cultural mentorship relationships. The third was to identify whether they could recognize and address specific challenges described in literature as minority taxes. Study questions assessed cross-cultural relationships between non-URiM mentors and URiM mentees.

This survey was part of a larger 2021 Uniformed Services Academy of Family Physicians (USAFP) Annual Meeting Omnibus Survey conducted by the Clinical Investigations Committee (CIC) of USAFP. The CIC iteratively evaluated the questions we submitted for validity, consistency with project aim, and existing evidence of reliability. Questions were modified following pretesting for flow, timing, and readability, if needed, and entered them into SurveyMonkey, an electronic survey program. The CIC added general demographics questions in multiple-choice and fill-in format. The project was preapproved by the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences Institutional Review Board as an exempt protocol in March 2020.

The sampling frame for the survey included all USAFP family physicians registered to attend the 2021 scientific assembly. The 15 CIC members involved in the survey methodology were excluded from participation in taking the survey. We collected data from participants anonymously via a link supplied at the meeting. We sent three follow-up email survey invitations. Respondents self-reported demographics, cross-cultural mentorship relationships, confidence and skills in discussing racism, and ability to recognize and address minority taxes. We categorized survey questions with 4-point and 5-point scales into two response categories. We categorized questions regarding confidence and skills as confident/not confident and skills/no skills, respectively. Similarly, we categorized questions regarding understanding and ability to recognize minority taxes as understand/do not understand and recognize/cannot recognize, respectively.

We performed descriptive statistics and bivariate associations using SPSS Statistics (IBM) software. Summary statistics included mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. Group comparisons were conducted using χ2 tests, independent samples t tests, Fisher’s exact tests, and Wilcoxon’s rank sum tests, as appropriate. Two-sided statistical tests were conducted assuming α=0.05.

Of the 487 attendees who met inclusion criteria, 258 responded to the survey. Ten percent of respondents were from URiM groups, and 54.3% of respondents identified as male. Additional respondent characteristics are shown in Table 1.

|

All respondents (N=258)

|

|

Self-reported race/ethnicity

|

None/no response (n)

|

Clinical instructor (n)

|

Assistant professor (n)

|

Associate professor (n)

|

Professor (n)

|

Total, n (%)

|

|

Black or African American

|

4

|

0

|

6

|

1

|

0

|

11 (4.3)

|

|

Hispanic or Latin-X including Puerto Rican

|

7

|

0

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

10 (3.9)

|

|

White

|

90

|

6

|

86

|

15

|

3

|

200 (77.5)

|

|

Asian or Pacific Islander

|

9

|

1

|

3

|

4

|

0

|

17 (6.6)

|

|

Native American (American Indian, Native Hawaiian, Alaskan Native)

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1 (0.4)

|

|

Other (multi, other, no response)

|

7

|

1

|

4

|

0

|

0

|

12 (4.3)

|

|

Prefer not to answer

|

3

|

0

|

4

|

0

|

0

|

7 (3)

|

|

|

|

Respondents with APD/PD experience

|

|

Self-reported race/ethnicity

|

None/no response (n)

|

Clinical instructor (n)

|

Assistant professor (n)

|

Associate professor (n)

|

Professor (n)

|

Total (N=62)

|

|

Black or African American

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

3 (4.8)

|

|

Hispanic or Latin-X including Puerto Rican

|

0

|

0

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

1 (1.6)

|

|

White

|

6

|

0

|

38

|

8

|

3

|

55 (88.7)

|

|

Asian or Pacific Islander

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0 (0)

|

|

Native American (American Indian, Native Hawaiian, Alaskan Native)

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0 (0)

|

|

Other

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

0

|

0

|

3 (4.8)

|

Fifty-three percent of respondents did not have a URiM physician mentee, and 55% had not collaborated with a URiM physician colleague on a scholarly activity within the last 3 years. Most respondents felt that they understood the historical context of racism (75.2%), had the skills to discuss racism (62.8%), and had the confidence to discuss racism (60.5%). However, only 54.7% felt that they could recognize and address minority taxes. Table 2 shows the overall survey responses of all respondents, URiM versus non-URiM responses, and responses from those with and without a URiM mentee.

|

Survey question

|

Overall all respondents (N=258), n (%)

|

|

URiM respondents vs non-URiM respondents

|

|

URiM mentorship all respondents

|

|

URiM (n=26), n (%)

|

non-URiM (n=232), n (%)

|

URiM mentee (n=120), n (%)

|

No URiM mentee (n=138), n (%)

|

|

Do you consider yourself a mentor for someone who is underrepresented in medicine?

|

URiM mentee

|

120 (45.6)

|

17 (65.4)

|

103 (44.4)

|

|

|

Not URiM mentee

|

138 (53.5)

|

9 (34.6)

|

129 (55.6)

|

|

|

P=.042

|

|

Are you confident discussing structural, systemic, and interpersonal racism in mentorship relationships with those underrepresented in medicine?

|

Confident

|

162 (62.8)

|

22 (84.6)

|

140 (60.3)

|

84 (70)

|

78 (56.5)

|

|

Not confident

|

96 (37.2)

|

4 (15.4)

|

92 (39.6)

|

36 (30)

|

60 (43.5)

|

|

|

P=.015

|

P=.025

|

|

Do you have the skills to discuss structural, systemic, and interpersonal racism in mentorship relationships with those underrepresented in medicine?

|

Skills

|

156 (60.5)

|

21 (80.8)

|

135 (58.2)

|

85 (70.8)

|

71 (51.4)

|

|

No skills

|

102 (39.5)

|

5 (19.2)

|

97 (41.8)

|

35 (29.2)

|

67 (48.6)

|

|

|

P=.026

|

P=.001

|

|

Do you understand the historical context of structural, systemic, and interpersonal racism?

|

Understand

|

194 (75.2)

|

23 (88.5)

|

171 (73.7)

|

93 (77.5)

|

101 (73.2)

|

|

Do not understand

|

64 (24.8)

|

3 (11.5)

|

61 (29.3)

|

27 (22.5)

|

37 (26.8)

|

|

|

P=.099

|

P=.424

|

|

Are you able to recognize and address the challenges termed “minority taxes” faced by those underrepresented in medicine?

|

Recognize

|

141 (54.7)

|

22 (84.6)

|

119 (51.3)

|

75 (62.5)

|

66 (47.8)

|

|

Cannot recognize

|

117 (45.3)

|

4 (15.4)

|

113 (48.7)

|

45 (37.5)

|

72 (52.2)

|

|

|

|

P=.001

|

P=.018

|

|

Within the last 3 years, have you collaborated in a scholarly activity with a physician identified as underrepresented in medicine?

|

URiM collaboration

|

114 (44.2)

|

11 (42.3)

|

103 (44.4)

|

75 (62.5)

|

39 (28.3)

|

|

No URiM collaboration

|

144 (55.8)

|

15 (57.7)

|

129 (55.6)

|

45 (37.5)

|

99 (71.7)

|

|

|

|

P=.839

|

P=0.0

|

|

How often have you been affected by structural, systemic, or interpersonal racism in your medical career?

|

Affected

|

58 (22.5)

|

17 (65.4)

|

41 (17.7)

|

35 (29.2)

|

23 (16.7)

|

|

Not affected

|

200 (77.5)

|

9 (34.6)

|

191 (82.3)

|

85 (70.8)

|

115 (83.3)

|

|

|

|

P=0.0

|

P=.016

|

URiM physician respondents were more likely to have a URiM physician mentee (65.4% vs 44.4%, P=.042), more confident discussing racism (84.6% vs 60.3%, P=.015), more likely to recognize and address minority taxes (84.6% vs 51.3%, P=.001), and more likely to feel more skilled to discuss racism (80.8% vs 58.2%, P=.026). Sixty-five percent of URiM physicians responded that they had been affected by racism in their medical career.

Respondents who had a URiM physician mentee were more confident discussing racism (70% vs 56.5%, P=.025), more likely to recognize and address minority taxes (62.5% vs 47.8%, P=.018), more likely to have collaborated with a URiM physician in the last 3 years (62.8% vs 28.3%, P=0.0), and more likely to feel more skilled to discuss racism (70.8% vs. 51.4%, P=.001).

Within our data set, URiM military family physician demographics are consistent with civilian data in regard to overall URiM composition 1 and academic promotion (Table 1). 7 Only approximately 50% could recognize and address minority taxes. Furthermore, more than half of respondents did not have a URiM physician mentee and had not collaborated with a URiM physician colleague on a scholarly activity within the last 3 years. The lack of statistical significance between URiM and non-URiM physicians’ scholarly activity collaboration with a URiM physician may be representative of the impact of minority taxes on scholarly activity. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate cross-cultural mentorship practices among military family medicine physicians.

The first limitation to this survey was that the survey demographics questions combined Asian, a non-URiM physician group, and Pacific Islander. This was not considered to have a significant impact on outcomes given the overall low population of the Pacific Islander minority group in medicine, approximately 0.1%. 1 Second, although USAFP represents more than 3,000 military physicians, the survey was available only to registered conference attendees, less than 20% of membership. 18 Lastly, while our study demographics mirrored civilian data, unique military factors such as pay equality, esprit de corps, and an interconnected global professional network built through duty reassignments may limit study generalizability because nonmilitary physicians may not have these experiences that influence their career trajectory.

Military family medicine has had a tradition of producing physician leaders who have responded to addressing disparities in physician retention and career development. The Military Health System (MHS) Council for Female Physician Recruitment and Retention and the annual MHS Female Physician Leadership Course (FPLC) were implemented to address higher attrition rates of women physicians and the lower percentages of military women physicians serving in leadership positions. 8, 19 Like gender disparities, addressing racial/ethnic disparities in medicine will require similar programs. 20 Mentors involved in these programs must have the skills to recognize, address, and mitigate the negative effects of minority taxes. 15, 16 Some specific skills are listed earlier in Figure 1.

This initial study suggests that, while some cross-cultural URiM physician mentorship is occurring, it could be significantly improved. Furthermore, our study results are timely and aligned with the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine’s key initiatives of antiracism and supporting the professional growth of URiM physicians. Additional studies are needed to implement programs and identify opportunities to improve URiM physician pathways in medicine.

This study was presented in the Podium Research Competition at the Uniformed Services Academy of Family Physicians (USAFP) Annual Meeting, March 30–April 4, 2022, in Anaheim, California.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of the Navy, the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Fort Belvoir Community Hospital, the US Department of Defense, or the US government.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Michael Arnold, MD, the USAFP Clinical Investigations Committee, and Christy Ledford, PhD, FACH, for their contributions in the distribution of survey, data analysis, and/or review of this manuscript.

References

-

-

-

Guevara JP, Adanga E, Avakame E, Carthon MB. Minority faculty development programs and underrepresented minority faculty representation at US medical schools.

JAMA. 2013;310(21):2297-2,304.

doi:10.1001/jama.2013.282116

-

Ansell DA, McDonald EK. Bias, Black lives, and academic medicine.

N Engl J Med. 2015;372(12):1,087-1,089.

doi:10.1056/NEJMp1500832

-

Odei BC, Jagsi R, Diaz DA, et al. Evaluation of equitable racial and ethnic representation among departmental chairs in academic medicine, 1980-2019.

JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(5):e2110726.

doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10726

-

Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Syed ZA, Shakil A, Schneider FD. Recent trends in faculty promotion in U.S. medical schools: implications for recruitment, retention, and diversity and inclusion.

Acad Med. 2021;96(10):1,441-1,448.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004188

-

Fassiotto M, Flores B, Victor R, et al. Rank equity index: measuring parity in the advancement of underrepresented populations in academic medicine.

Acad Med. 2020;95(12):1,844-1,852.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003720

-

Massaquoi MA, Reese TR, Barrett J, Nguyen D. Perceptions of gender and race equality in leadership and advancement among military family physicians.

Mil Med. 2021;186(suppl 1):762-766.

doi:10.1093/milmed/usaa387

-

Ayyala MS, Skarupski K, Bodurtha JN, et al. Mentorship is not enough: exploring sponsorship and its role in career advancement in academic medicine.

Acad Med. 2019;94(1):94-100.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002398

-

Levine RB, Ayyala MS, Skarupski KA, et al. “It’s a little different for men”—sponsorship and gender in academic medicine: a qualitative study.

J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(1):1-8.

doi:10.1007/s11606-020-05956-2

-

-

Radha Krishna LK, Renganathan Y, Tay KT, et al. Educational roles as a continuum of mentoring’s role in medicine—a systematic review and thematic analysis of educational studies from 2000 to 2018.

BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):439.

doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1872-8

-

Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Pololi LH. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax?

BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):6.

doi:10.1186/s12909-015-0290-9

-

Ziegelstein RC, Crews DC. The majority subsidy.

Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(11):845-846.

doi:10.7326/M19-1923

-

Campbell KM, Rodríguez JE. Mentoring underrepresented minority in medicine (URMM) students across racial, ethnic and institutional differences.

J Natl Med Assoc. 2018;110(5):421-423.

doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2017.09.004

-

Campbell KM, Rodríguez JE. Addressing the minority tax: perspectives from two diversity leaders on building minority faculty success in academic medicine.

Acad Med. 2019;94(12):1,854-1,857.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002839

-

Jacobs CK, Everard KM, Cronholm PF. Promotion of clinical educators: A critical need in academic family medicine.

Fam Med. 2020;52(9):631-634.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.687091

-

Uniformed Service Academy of Family Physicians (USAFP). Accessed January 30, 2022.

https://usafp.org

-

Nakamura TA, Nguyen DR. Advice for leading and mentoring women physicians in the MHS.

Mil Med. 2019;184(9-10):e376-e378.

doi:10.1093/milmed/usz117

-

There are no comments for this article.