Background and Objectives: Many health conditions are preventable or modifiable through behavioral changes. Motivational interviewing (MI) is an evidence-based communication technique that explores a patient’s reasons for behavioral changes. This study assesses the current landscape of MI training in North American Family Medicine (FM) clerkships.

Methods: We analyzed data gathered as part of the 2022 Council of Academic Family Medicine’s Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of FM clerkship directors (CDs). The survey was distributed via email invitation to 159 US and Canadian FM CDs in June 2022.

Results: Of the 94 responses received, 61% indicated that MI training is provided in their FM clerkship. Medical school type, class size, and location were associated with MI training priority, offerings, and duration in the clerkship, respectively. CD experience correlated with MI training duration; student MI skill training level was associated with MI training duration and priority; the rigor of student MI skills evaluation was correlated with MI teaching methods and training duration; self-reported student MI competency was associated with the length of time students spent with FM community preceptors as well as MI training priority and teaching methods; and several items emerged as predictors of student, CD, and FM faculty MI training expansion.

Conclusions: Opportunities exist to enhance the volume, content, and rigor of MI training in North American FM clerkships as well as to improve self-reported student MI competency within those clerkships.

Many health conditions, such as diabetes, hypertension, and cancer, are preventable or modifiable through health behavior changes such as losing weight, increasing physical activity, eating a healthier diet, and quitting smoking. 1-3 From 2010 to 2017, midlife mortality (ages 25-64 years) has increased in the United States from a rate of 328.5 deaths per 100,000 to 348.2 deaths per 100,000 due to chronic disease, alcohol overuse, suicide, and drug overdoses—all illnesses that have a behavioral component. 4

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a patient-centered evidence-based communication technique to support behavior change by exploring a patient’s reasons for making or avoiding behavioral changes while providing an environment of acceptance and compassion. In MI, the clinician uses open-ended questions, reflective listing, and empathetic statements to encourage patients to explore their ambivalence about behavioral change. Clinicians are coached to avoid the expert role and instead listen to patient ideas about how to improve their health. 5, 6 Recent meta-analyses support the use of MI to positively influence patient health behaviors, including smoking cessation, reduction in alcohol use, weight loss, and medication adherence, with demonstrated improvements in cardiovascular health, diabetes care, and childhood obesity.6-13 Although the literature has shown the benefit of MI on behavior changes, the impact of MI may be less among patients who identify as Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC),14 particularly in situations where the patient is seeking direct instruction from the clinician about making behavior changes. 15 We look forward to future research on unique factors that influence BIPOC community members to embark on behavior change to improve their health.

Given the prevalence of behavior-dependent health conditions, physicians-in-training should be knowledgeable and have some basic competency in MI skills in order to foster behavior change in patients. 1, 2 Increasing the capacity of physicians-in-training to effectively support their patients through MI-based approaches not only has the potential to support positive behavior change among patients but also more broadly supports foundational physician communication competencies driving clinical care. A review of MI in graduate medical education (GME) supported the use of MI to improve resident self-efficacy in managing chronic health conditions. 16 However, teaching MI in undergraduate medical education (UME) has traditionally been limited, pedagogical approaches have been heterogenous, and uncertainty surrounds the optimal time to teach patient-centered interventions—during the preclinical years, clinical years, or both. 2

Based on definitions and criteria from a recent systematic review, UME MI training can be classified as basic, intermediate, or advanced in content, educational methods, and evaluation. 2 Basic MI education covers awareness content (eg, patient-centered care, goal-setting); intermediate MI education teaches core components of MI (eg, OARS [open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, summaries], importance/confidence [readiness] rulers); and advanced MI education incorporates skill-building (eg, eliciting change talk, using ambivalence to provoke change, integrating MI within the clinical visit). 2, 6 Basic MI education includes passive learning modalities (eg, didactics, readings, video demonstrations, online modules) to introduce MI concepts and techniques to learners; intermediate MI education adds limited active learning modalities (eg, role plays, type-in responses); and advanced MI education adds real and/or standardized patients to allow learners to practice MI techniques and receive feedback about learners’ performance.2, 6, 17-20 Basic MI education programs are typically brief in duration (<2 hours) while intermediate and advanced MI education programs are typically longer in duration (≥2 hours).2 Evaluation can be aligned with instructional approaches. For example, for basic MI education, instructors might use measures such as surveys, self-reported efficacy, multiple-choice questions, or essays; while for intermediate MI education, they might use faculty observation of patient encounters with personalized feedback or an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) with standardized patients. For advanced MI education, validated assessment tools such as the Behaviour Change Counselling Index (BECCI) or Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) might be used. 16, 18, 21, 22

The specialty of family medicine (FM) emphasizes disease prevention, health promotion, and the biopsychosocial approach to patient care. 23 MI is part of the National Clerkship Curriculum created by the Society for Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) and is considered a core training component in the FM clerkship. 23 As such, FM clerkships may play a pivotal role in developing MI competencies in the future physician workforce. While studies and systematic reviews detailing heterogeneous MI curricula in UME, GME, and clinical settings exist, a paucity of literature focuses on the state of MI education in North American FM clerkships and the status of UME MI training after the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have impacted attitudes and educational time for MI. The purpose of this study was to describe the current landscape of MI education in North American FM clerkships, including identification of programmatic characteristics associated with implementation and expansion of MI education in FM clerkships and exploration of how FM clerkship director (CD) attitudes about MI and personal interest in MI training might impact MI education in their clerkships.

We analyzed data gathered as part of the 2022 Council of Academic Family Medicine’s Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of FM CDs. 24 This cross-sectional survey is distributed annually to CDs at accredited medical schools located within the United States of America and Canada. The survey was distributed via email invitation to 148 US and 16 Canadian FM CDs between June 7, 2022, and July 8, 2022. Five clerkships were removed from the sample due to incorrect email contact information, resulting in 159 delivered invitations. The study was approved by the American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board in June 2022.

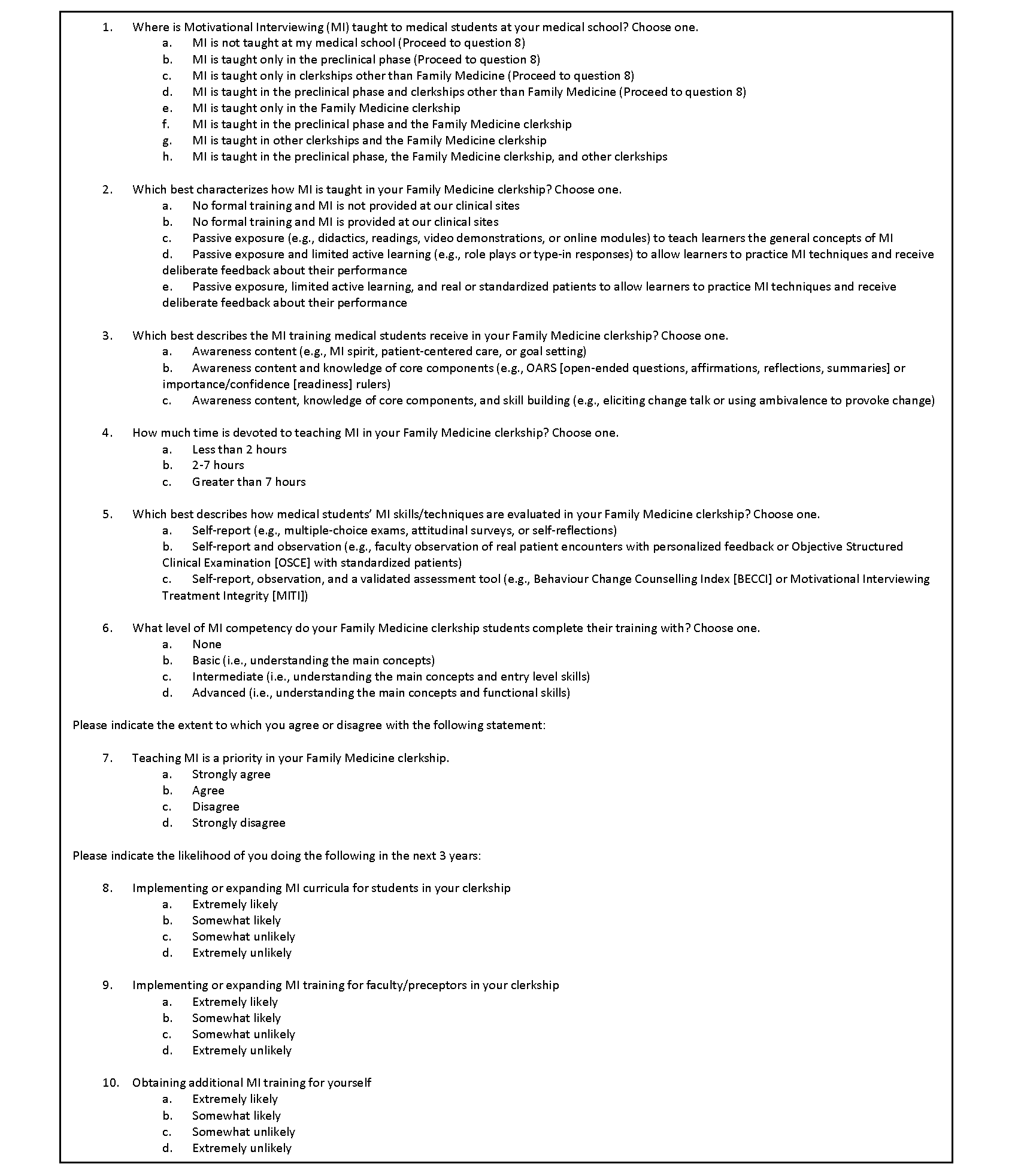

Core items included in the CERA survey included variables characterizing the medical school, the FM clerkship, and the CD. Medical school variables included the school’s classification as public versus private and location (aggregated into nine US regions and Canada). Variables describing the FM clerkship included class size (dichotomized to ≤150 or >150), block versus longitudinal structure, duration of the clerkship (dichotomized to ≤4 weeks or >4 weeks), and amount of time students spent with community preceptors (dichotomized to ≤50% or >50%). Our team developed CERA items (Figure 1) to describe UME MI training in the FM clerkship, including characterizing how MI was taught (if at all) to medical students. We used skip logic so that only programs that answered response options e–h in question 1 were then offered questions 2–7.

We collected content validity evidence through literature review and the survey development team’s content expertise in MI. We demonstrated response process validity and internal consistency by pilot testing among the research team and including survey design experts on the team. Survey items describing the timing and placement of MI curricula were presented in categories, including preclinical, non-FM clerkship, and FM clerkship (as well as overlapping combinations).

FM clerkship MI teaching methods were categorized in an ordinal manner into passive (eg, didactics, readings, video demonstrations, or online modules) to teach learners the general concepts of MI, passive with limited active learning (eg, role plays or type-in responses), and passive with limited active learning along with real and/or standardized patients. MI curricula were further characterized ordinally across awareness, knowledge, and skill-building approaches. The duration of FM clerkship MI curricula time was dichotomized into <2 hours or ≥2 hours.

Importantly, we examined FM clerkship MI evaluation methods, which were dichotomized into self-report (eg, multiple-choice exams, attitudinal surveys, self-reflections) or observation/use of validated instruments by an external observer. Variables related to the CD’s attitudes and opinions of MI included whether MI was identified as a training priority; response options were dichotomized into agreement (strongly agree/agree) compared to disagreement (disagree/strongly disagree). Our survey captured the CDs’ likelihood of implementing or expanding MI training for FM clerkship students, faculty, and themselves with responses of extremely likely/somewhat likely compared to somewhat unlikely/extremely unlikely. We provided univariate descriptive statistics to illustrate frequencies and proportions of the described variables. We assessed bivariate associations using the tabulate function in Stata version 17 (StataCorp) to calculate χ2 statistics and expected values for categorical variables. We used a P value of .05 as the level of statistical significance.

Of the 159 FM CDs, 94 (59%) responded to the CERA survey. Demographic characteristics are noted in Table 1. Fifty-seven CDs (61%) indicated that MI was taught in their FM clerkship. Twenty-seven CDs (29%) reported that MI was taught only in the preclinical phase of their medical school curriculum. Only sixteen (29%) of the FM clerkships teaching MI allotted ≥2 hours toward MI instruction. Slightly less than half (45%) of FM clerkships that offered MI education incorporated robust teaching methods (passive exposure, limited active learning, and real or standardized patients). Seventy-three percent of FM clerkships with MI training programs reported incorporating observation as a method of MI evaluation. FM clerkship MI curricula characteristics are detailed in Table 2. Not all respondents answered all the questions.

Several significant associations between medical school/FM clerkship characteristics and FM clerkship MI training are highlighted in Appendix Table A.

|

Measure

|

Frequency (%)

|

|

Medical school characteristics

|

|

Type

|

|

Public

|

65 (70)

|

|

Private

|

28 (30)

|

|

Location

|

|

New England

|

8 (9)

|

|

Middle Atlantic

|

10 (11)

|

|

South Atlantic

|

20 (21)

|

|

East South Central

|

6 (6)

|

|

East North Central

|

10 (11)

|

|

West South Central

|

8 (9)

|

|

West North Central

|

8 (9)

|

|

Mountain

|

7 (7)

|

|

Pacific

|

4 (4)

|

|

Canada

|

13 (14)

|

|

Class size

|

|

≤150

|

47 (50)

|

|

>150

|

47 (50)

|

|

FM clerkship characteristics

|

|

Design

|

|

Block

|

65 (69)

|

|

Longitudinal

|

5 (5)

|

|

Block and Longitudinal

|

24 (26)

|

|

Block-only length

|

|

≤4 weeks

|

21 (32)

|

|

>4 weeks

|

44 (68)

|

|

Block-only or b lock and longitudinal length

|

|

≤4 weeks

|

28 (31)

|

|

>4 weeks

|

61 (69)

|

|

Student time spent with community preceptors

|

|

≤50%

|

37 (40)

|

|

>50%

|

55 (60)

|

|

FM clerkship director characteristics

|

|

Current y ears in role

|

|

≤5

|

42 (45)

|

|

6-10

|

28 (30)

|

|

>10

|

24 (26)

|

|

Training period

|

|

>10 years ago

|

67 (73)

|

|

6-10 years ago

|

20 (22)

|

|

≤5 years ago

|

5 (5)

|

|

Measure

|

Frequency (%)

|

|

MI taught in medical school (N=94)

|

|

Not taught

|

1 (1)

|

|

Only in preclinical phase

|

27 (29)

|

|

Only in non-FM clerkship

|

2 (2)

|

|

Only preclinical phase and non-FM clerkship

|

7 (7)

|

|

Only in FM clerkship

|

3 (3)

|

|

Preclinical phase and FM clerkship

|

25 (27)

|

|

FM and other clerkships

|

3 (3)

|

|

Preclinical phase, FM, and other clerkships

|

26 (28)

|

|

MI taught in F M clerkship (N=94)

|

|

No

|

37 (39)

|

|

Yes

|

57 (61)

|

|

MI teaching method in FM clerkship (N=57)

|

|

Passive exposure

|

10 (18)

|

|

Passive exposure and limited active learning

|

17 (31)

|

|

Passive exposure, limited active learning, and real or standardized patients

|

25 (45)

|

|

No formal training; provided at clinical sites

|

3 (5)

|

|

MI skills training in FM clerkship (N=57)

|

|

Awareness content

|

14 (25)

|

|

Awareness content and knowledge of core components

|

17 (31)

|

|

Awareness content, knowledge of core components, and skill-building

|

24 (44)

|

|

FM clerkship time devoted to MI (N=57)

|

|

<2 hours

|

39 (71)

|

|

≥2 hours

|

16 (29)

|

|

MI evaluation method in FM clerkship (N=57)

|

|

Self-report

|

14 (27)

|

|

Self-report and observation

|

38 (73)

|

|

MI competency in FM clerkship (N=57)

|

|

Basic or less

|

19 (35)

|

|

Intermediate or more

|

36 (65)

|

|

MI priority in FM clerkship (N=57)

|

|

Disagree

|

12 (21)

|

|

Agree

|

44 (79)

|

|

Expanding student MI training (N=94)

|

|

Unlikely

|

54 (59)

|

|

Likely

|

37 (41)

|

|

Expanding FM faculty MI training (N=94)

|

|

Unlikely

|

58 (64)

|

|

Likely

|

33 (36)

|

|

Expanding CD MI training (N=94)

|

|

Unlikely

|

54 (59)

|

|

Likely

|

37 (41)

|

Medical School Type, Class Size, and Location

FM CDs at public medical schools were more likely to agree that MI training was a priority in their clerkship. MI training was more likely to be offered in FM clerkships with larger medical school class sizes. FM clerkships in the United States were more likely to spend <2 hours on MI training than FM clerkships in Canada; among the US FM clerkships, there were no geographical differences in MI training duration.

Student MI Skill Training in FM Clerkship

FM clerkships that incorporated skill-building into their MI training were more likely to provide ≥2 hours of MI education, and the CD was more likely to agree that MI training is a priority in the clerkship.

Clerkship Director Experience

FM CDs who were newer to their roles were more likely to have <2 hours of MI training in their clerkships than CDs with more experience in the role.

MI Competency in FM Clerkship

More than half of students’ time being spent with community preceptors during the FM clerkship was associated with a higher self-report of student MI competency by the CD. Also, CDs were more likely to self-report a higher level of student MI competency when the CD endorsed MI training as a priority, and when the educational program incorporated real or standardized patients to teach MI.

Predictors of MI training expansion in FM clerkships are detailed in Table 3.

|

Measure

|

Frequency (%)

|

|

Unlikely

|

Likely

|

|

Expanding student MI training

|

|

MI teaching method (N=55) ; P =.031

|

|

|

Passive

|

3 (9)

|

7 (33)

|

|

Passive and limited

|

9 (26)

|

8 (38)

|

|

Passive, limited, and patients

|

19 (56)

|

6 (29)

|

|

No training but clinical

|

3 (9)

|

0 (0)

|

|

Expanding FM CD MI training (N=91); P <.0001

|

|

|

Unlikely

|

44 (81)

|

10 (27)

|

|

Likely

|

10 (19)

|

27 (73)

|

|

|

Expanding FM faculty MI training

|

|

Class size (N=91) ; P =.041

|

|

|

≤150

|

24 (41)

|

21 (64)

|

|

>150

|

34 (59)

|

12 (36)

|

|

Expanding student MI training (N=91); P <.0001

|

|

|

|

Unlikely

|

47 (81)

|

7 (21)

|

|

Likely

|

11 (19)

|

26 (79)

|

|

Expanding FM CD MI training (N=91); P <.0001

|

|

|

Unlikely

|

45 (78)

|

9 (27)

|

|

Likely

|

13 (22)

|

24 (73)

|

|

|

Expanding FM CD MI training

|

|

Current years as FM CD (N=91) ; P=.058

|

|

|

≤5 years

|

19 (46)

|

22 (54)

|

|

6-10 years

|

17 (65)

|

9 (35)

|

|

>10 years

|

18 (75)

|

6 (25)

|

|

Expanding student MI t raining (N=91); P <.0001

|

|

|

Unlikely

|

44 (81)

|

10 (27)

|

|

Likely

|

10 (19)

|

27 (73)

|

|

Student MI skill-building level in FM clerkship (N=55) ; P =.014

|

|

|

Awareness

|

7 (21)

|

7 (33)

|

|

Awareness and core

|

7 (21)

|

10 (48)

|

|

Awareness, core, and skill

|

20 (59)

|

4 (19)

|

|

MI evaluation method (N=52) ; P =.030

|

|

|

Self-report

|

12 (38)

|

2 (10)

|

|

Self-report and observation

|

20 (63)

|

18 (90)

|

Expanding Student MI Training

FM CDs were more likely to expand MI training for students if the education program had passive or limited instructional methods and if the CDs were looking to expand their own training on MI.

Expanding FM Faculty MI Training

FM CDs were more likely to expand MI training for faculty within the clerkship if the class size was ≤150 students and if they were likely to expand MI training for both students and themselves.

Expanding Clerkship Director MI Education

FM CDs were more likely to expand MI training for themselves if they had been in the CD role for ≤5 years, were likely to expand MI training for their students, were not using skill-building in the MI training program, and were using more rigorous evaluation techniques in the MI training program.

This study characterized the current state of MI education in North American FM clerkships and added to the literature on MI by informing how medical schools have implemented MI training specifically within FM clerkships. Interestingly, despite worsening US mortality statistics, evidence of the important role of MI in health outcomes, and the inclusion of MI as a core training component in STFM’s National Clerkship Curriculum, 23 we found that not all FM clerkships were implementing MI training, and a fair number of FM CDs reported that MI was taught only in the preclinical years at their school. Additionally, our study found that variability remained in how MI was taught and evaluated within FM clerkships and how critical feedback on MI performance—an important component to improving MI skill—was provided to FM clerkship students. We also learned that relatively little time was spent providing MI training in US FM clerkships regardless of their geographical location compared to FM clerkships in Canada. Our team hypothesized that this trend could be influenced by the clinical requirements US medical students must satisfy for graduation and ongoing accreditation requirements of US medical schools, which may take higher priority than MI training. In addition, we discovered that FM CDs who were newer to their roles were more likely to provide MI education programs that were brief in duration (<2 hours) compared to FM CDs with more experience in the role; our team hypothesized that differences in expertise with MI instructional and evaluation methods may have contributed to this finding. Because self-reported student MI competency by CDs was positively associated with characteristics of advanced MI training programs, which naturally require more programmatic time to deliver, devoting more time to MI training in FM clerkships will be important for strengthening medical students’ ability to effectively use MI in their clinical work.

This study also uniquely examined the attitudes and opinions of current FM CDs and may spur CDs to reflect on how their attitudes toward MI and personal interest in MI training could impact their clerkship’s MI curricula. We found that slightly more than half of respondents indicated that their FM clerkship offered MI training for students, suggesting that important opportunities are available to implement and expand MI training in more FM clerkships across North America. In addition, our study suggested that when CDs endorsed MI training as a priority in the FM clerkship, the MI educational programming in the clerkship tended to be more advanced and CDs self-reported higher student MI competency. CDs’ interest in expanding their own personal MI training tended to come with an inclination to expand student and faculty training in MI.

An intriguing finding in our study was that the more time students spent working with community preceptors during the FM clerkship, the higher the level of perceived student MI competency indicated by CDs. This finding may reflect the reality of primary care visits in community-based practices where behavioral health concerns are frequently encountered and MI skill is needed. This finding also suggests that FM clerkships desiring to achieve high levels of perceived student MI competency may be able to identify and/or develop community preceptors who model this behavior for students. Thus, implementing strong MI curricula in FM clerkships may be enhanced by training and retraining community preceptors over time. Minimal MI training may be all that is necessary for community preceptors; a study by Strayer et al exploring relationships between MI, behaviors of primary care clinicians, and patient attempts to quit smoking found that brief MI training interventions (1-2 hours) in the primary care office resulted in higher smoking cessation rates 6 months after the counseling took place. 25 In addition, physicians in that study already were performing MI global skills at recommended levels prior to training.25 This finding underscores that community preceptor MI skills training can be brief and focused while still being effective.

This work has several potential limitations. There may be more nuanced approaches to teaching MI that could not be explored through this survey mechanism. In some schools, strong partnerships may exist between one or more clerkships (eg, family medicine, internal medicine, psychiatry) with limited MI training within the FM clerkship but offered elsewhere in the medical school. The data were self-reported and based on CDs’ assessments, which may be subject to social desirability and limited to the opinion of a single individual. For example, CDs reported on overall student MI competency, which is comprised of several different skills. More objective methods to assess MI competency in FM clerkships exist, such as the BECCI 21 or the MITI 22; such assessment was beyond the scope of this survey but warrants further study. The data were cross-sectional, potentially missing changes and trends in MI education related to curricular priorities driven by the COVID-19 pandemic; some programs may have implemented more MI education due to more widespread telehealth implementation, while others may have limited MI education due to other educational priorities. Finally, our study did not examine the availability of financial resources or local expert MI trainers to provide additional teaching support to clerkships that incorporated MI education, and this may be an area for additional study.

Future research is needed to better characterize MI frequency and techniques used in FM practices, which could be helpful to CDs in their efforts to better map MI education among faculty preceptors and students. Developing and building faculty (including community preceptors) who are MI champions can be important to expanding training efforts. Identifying US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines, where MI interventions may be most helpful (eg, obesity, smoking cessation), and providing continuing medical education credit for MI training for faculty may also be important. To strengthen their MI skills, providing students, faculty, and CDs with detailed feedback on their MI performance is critical. In-the-moment coaching may be best, such as can occur in integrated care practices where medical clinicians are paired with mental/behavioral health providers 26; partnering with allied providers (eg, therapists, psychologists, pharmacists) who extensively use MI may also be optimal because such partnerships may also yield informal training to FM preceptors. 26 Determining factors that influence MI education priority and CD decisions about MI instructional and evaluation methods would provide insight into the variations that exist among FM clerkship MI educational offerings and are potential areas for future research. Identifying MI educational resources that are feasible for CDs’ busy schedules is an important and necessary next step in building advanced MI training programs in FM clerkships.

In conclusion, while MI education is occurring in slightly more than half of FM clerkships in North America, opportunities are available to enhance the volume, content, and rigor of MI training as well as to improve self-reported student MI competency within those clerkships. Given the pivotal role primary care clinicians have in effectively using MI to positively influence health behaviors associated with chronic disease, FM clerkships are particularly relevant and ideal spaces for student MI skill mastery.

Society of Teachers of Family Medicine 2023 Annual Spring Conference, April 29, 2023- May 3, 2023, Tampa, Florida, poster presentation.

University of Cincinnati receives funding for Dr Santen as a consultant for the American Medical Association.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sharon Kaufer Flores, MS, for assistance in creating the data tables and manuscript critique, the CERA Steering Committee and the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine staff for their assistance with data collection, and the CDs who responded to the survey.

References

-

Strayer SM, Martindale JR, Pelletier SL, Rais S, Powell J, Schorling JB. Development and evaluation of an instrument for assessing brief behavioral change interventions.

Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83(1):99-105.

doi:10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.012

-

Kaltman S, Tankersley A. Teaching motivational interviewing to medical students: a systematic review.

Acad Med. 2020;95(3):458-469.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003011

-

Vodovotz Y, Barnard N, Hu FB, et al. Prioritized research for the prevention, treatment, and reversal of chronic disease: recommendations from the lifestyle medicine research summit.

Front Med (Lausanne). 2020;7:585744.

doi:10.3389/fmed.2020.585744

-

Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959-2017.

JAMA. 2019;322(20):1,996-2,016.

doi:10.1001/jama.2019.16932

-

Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd ed. Guilford Press; 2012.

-

Kaltman S, WinklerPrins V, Serrano A, Talisman N. Enhancing motivational interviewing training in a family medicine clerkship.

Teach Learn Med. 2015;27(1):80-84.

doi:10.1080/10401334.2014.979179

-

Lundahl B, Moleni T, Burke BL, et al. Motivational interviewing in medical care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93(2):157-168.

doi:10.1016/j.pec.2013.07.012

-

Ling J, Wen F, Robbins LB, Pageau L. Motivational interviewing to reduce anthropometrics among children: A meta-analysis, moderation analysis and grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation assessment.

Pediatr Obes. 2022;17(8):e12896.

doi:10.1111/ijpo.12896

-

Ghizzardi G, Arrigoni C, Dellafiore F, Vellone E, Caruso R. Efficacy of motivational interviewing on enhancing self-care behaviors among patients with chronic heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

Heart Fail Rev. 2022;27(4):1,029-1,041.

doi:10.1007/s10741-021-10110-z

-

Bilgin A, Muz G, Yuce GE. The effect of motivational interviewing on metabolic control and psychosocial variables in individuals diagnosed with diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis.

Patient Educ Couns. 2022;105(9):2,806-2,823.

doi:10.1016/j.pec.2022.04.008

-

Marker I, Norton PJ. The efficacy of incorporating motivational interviewing to cognitive behavior therapy for anxiety disorders: A review and meta-analysis.

Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;62:1-10.

doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2018.04.004

-

Barrett S, Begg S, O’Halloran P, Kingsley M. Integrated motivational interviewing and cognitive behaviour therapy for lifestyle mediators of overweight and obesity in community-dwelling adults: a systematic review and meta-analyses.

BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1,160.

doi:10.1186/s12889-018-6062-9

-

Steele DW, Becker SJ, Danko KJ, et al. Brief behavioral interventions for substance use in adolescents: a meta-analysis.

Pediatrics. 2020;146(4):4.

doi:10.1542/peds.2020-0351

-

Befort CA, Nollen N, Ellerbeck EF, Sullivan DK, Thomas JL, Ahluwalia JS. Motivational interviewing fails to improve outcomes of a behavioral weight loss program for obese African American women: a pilot randomized trial.

J Behav Med. 2008;31(5):367-377.

doi:10.1007/s10865-008-9161-8

-

Grobe JE, Goggin K, Harris KJ, Richter KP, Resnicow K, Catley D. Race moderates the effects of motivational Interviewing on smoking cessation induction.

Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(2):350-358.

doi:10.1016/j.pec.2019.08.023

-

Dunhill D, Schmidt S, Klein R. Motivational interviewing interventions in graduate medical education: a systematic review of the evidence.

J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(2):222-236.

doi:10.4300/JGME-D-13-00124.1

-

Reger GM, Norr AM, Rizzo AS, et al. Virtual standardized patients vs academic training for learning motivational interviewing skills in the US Department of Veterans Affairs and the US military: a randomized trial.

JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2017348.

doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17348

-

Mitchell S, Heyden R, Heyden N, et al. A pilot study of motivational interviewing training in a virtual world.

J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(3):e77.

doi:10.2196/jmir.1825

-

Gecht-Silver M, Lee D, Ehrlich-Jones L, Bristow M. Evaluation of a motivational interviewing training for third-year medical students. Fam Med. 2016;48(2):132-135.

-

Herbst R, Rybak T, Meisman A, et al. A virtual reality resident training curriculum on behavioral health anticipatory guidance: development and usability study.

JMIR Pediatr Parent. 2021;4(2):e29518.

doi:10.2196/29518

-

Lane C, Huws-Thomas M, Hood K, Rollnick S, Edwards K, Robling M. Measuring adaptations of motivational interviewing: the development and validation of the Behavior Change Counseling Index (BECCI).

Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56(2):166-173.

doi:10.1016/j.pec.2004.01.003

-

Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Hendrickson SM, Miller WR. Assessing competence in the use of motivational interviewing.

J Subst Abuse Treat. 2005;28(1):19-26.

doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2004.11.001

-

-

Seehusen DA, Mainous AG III, Chessman AW. Creating a centralized infrastructure to facilitate medical education research.

Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):257-260.

doi:10.1370/afm.2228

-

Strayer S, Ingersoll K, Pelletier S, Conaway M, Wells K, Tanabe, K. Motivational interviewing in primary care: current practices and mechanisms of action for successful smoking cessation counseling. Poster presentation at: North American Primary Care Research Group Annual Meeting; December 1-5, 2012; New Orleans, LA. Session P215.

-

Pollak KI, Nagy P, Bigger J, et al. Effect of teaching motivational interviewing via communication coaching on clinician and patient satisfaction in primary care and pediatric obesity-focused offices.

Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(2):300-303.

doi:10.1016/j.pec.2015.08.013

There are no comments for this article.