Patient trust in the health care system—including the physician, health care team, hospital, and government experts—is critical to the provision of quality health care. The patient-physician relationship is particularly important in the provision of health care. That relationship has been linked not only to better patient outcomes but also to greater adherence to treatment recommendations. 1-3 Patients look to their physician to act in their best interest, provide accurate interpretation of tests and signs and symptoms, and make appropriate treatment recommendations. The physician is the medical expert, and patients trust the physician to provide accurate information and advice to improve their health. This patient-physician bond even extends to compliance with physician recommendations that are inconsistent with national guidelines. 4

Unfortunately, trust in government health agencies like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has been falling in some patient groups. 5 Among these groups is a measured rise in distrust of government experts and their corresponding health care advice. 6

The disregard for the expertise and recommendations from government health institutions can have deadly consequences. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed this distrust in government expertise and health care recommendations and the concomitant impact on health outcomes. Geographic regions with low trust in the CDC recommendations toward COVID-19 vaccination had low vaccine coverage and correspondingly high COVID-19 mortality. 7-9

Further, information embraced by the public from less reliable sources can create confusion, particularly as experts from the FDA and the CDC emphasize an opposite approach. Though the use of social media helps to disseminate messages in a very concise way, little room is left for nuance and scientific background. The messaging about the value of ivermectin as a treatment for COVID-19, for example, left some people confused. Although the FDA recommends against it on its consumer web page, some segments of the population have a strong level of support for it. 10, 11

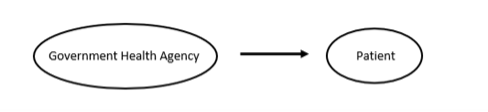

A primary messaging strategy used during the COVID-19 pandemic was to have the CDC director and individuals like Dr Anthony Fauci of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases market recommendations directly to the public. The agency director or government health figure was featured on television or in the media telling the public what to do. The message was that the health agency had reviewed all the scientific evidence, and the recommendation therefore was based on expert opinion. This strategy was built on the assumption that the expertise of these government health agencies was respected for presenting evidence-based recommendations in the best interest of patients and the public (Figure 1).

An analogy to this strategy is the direct-to-consumer marketing of pharmaceuticals. This type of advertising is somewhat controversial because the marketing by the pharmaceutical company bypasses the patient’s physician to directly influence the patient’s decision-making on treatment. These appeals complicate the patient-physician relationship because the information in the advertisements is limited and the patient lacks scientific expertise. The physician then must manage the patient’s request for a particular drug by educating the patient, explaining the drug in the context of the patient’s condition, and making a recommendation, which may be inconsistent with the advertising. In this way, the physician applies knowledge and expertise to match the patient’s values, needs, and health situation to the appropriate treatment option.

Similarly, the marketing strategy of having the government health agency director interpret evidence and make recommendations on prevention and treatment directly to the public essentially bypasses the patient-physician relationship and the role of the physician in recommendation of treatment. This strategy of direct messaging from the government health agency to the patient has become less and less effective in influencing patients and treatment, which has led to devastating public health consequences.

Primary care physicians are constantly acting as interpreters of complicated information for their patients. Think of a hub-and-spoke model with the primary care physician as the center hub and with radiology, laboratory services, and subspecialists as the spokes sharing information about the patient. Primary care physicians interpret the laboratory data, images, and information from the cardiologist for their patient, putting the findings in the context of what they know about the patient and the patient’s family, values, and comorbidities. The primary care physician then discusses the test results and treatment plan with the patient. Patients are not expected to receive and interpret all that technical information on their own.

Providing recommendations to a general population that is not skilled in medicine, science, and evaluation of scientific data seems to be a pathway that is easily influenced by misinformation from opinion leaders, celebrities, and others; those individuals also may not be knowledgeable in medicine or science but are seen as trustworthy and are experts in communicating data as fact. 9 A new strategy needs to be considered to improve the health of patients who may have low trust in government health agencies. This new strategy would build on a known way of providing medical information to patients: through the power and trust inherent in the patient-physician relationship. 12

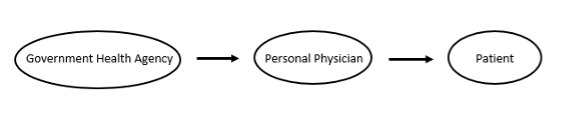

Figure 2 illustrates a pathway for information to travel from the government health agency through the physician and on to the patient.

In this way, the personal physician, in most cases a primary care physician, is the interpreter of scientific information and provider of recommendations for the patient. Patients trust their doctors, and likely trust their advice more than that of a celebrity, to look out for their best interests regarding their health. For patients without a primary care physician, or access to one, issues become more complicated; data show that continuity with a specific provider has advantages that continuity with a practice doesn’t have. 13, 14

A model with a similar pathway that has demonstrated success is that of recruiting patients into clinical trials. For some types of conditions, the investigator builds trust with community physicians, who already are trusted by their patients. 14, 15 Thus, rather than sending complicated information to the patient, the scientific information about the clinical trial is conveyed to the community physician who then interprets it for the patient. Patients trust their physician to look out for their best interest, interpret information for them, and provide a recommendation.

The current strategy of direct appeals to the public by government health agencies and their directors seems to be creating more opportunities for misinformation and confusion regarding health recommendations than was ever expected. In a crowded marketplace of voices, experts such as the director of the CDC are competing with celebrities such as Joe Rogan on treatment recommendations. A segment of the population does not value the scientific and medical expertise of government officials nor trust those experts. Patients do trust their doctors and their doctors’ advice.

To achieve the pathway that puts the physician as the primary interpreter of health information and recommender of treatment requires two elements. First, physicians—family physicians, in particular—need to actively take on the role of recommending evidence-based and guideline-based treatments to their patients. Rather than waiting for a question from the patient, the physician needs to recommend the appropriate therapy and explain it to the patient, thereby building on their relationship. The physician is in a key trusted position to provide accurate information to counteract misinformation. If physicians aren’t able to provide the information in a face-to-face encounter for every question, providing their patients with an endorsement of certain sources of health information is an option.

Second, government health agency directors need to deemphasize their role as the face of health information for the public. A change in strategy for disseminating health information is clearly needed and would help to defuse these leaders as lightning rods of public anger. The agencies need to continue to provide patient education, which is an integral part of public health. However, they need to focus more on letting individual physicians, rather than the agency director, be the ones to disseminate agency recommendations to patients. In this way, the central role of the patient-physician relationship can help ensure better health and restore trust in governmental health agencies.

References

-

Piette JD, Heisler M, Krein S, Kerr EA. The role of patient-physician trust in moderating medication nonadherence due to cost pressures.

Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(15):1,749-1,755.

doi:10.1001/archinte.165.15.1749

-

Altice FL, Mostashari F, Friedland GH. Trust and the acceptance of and adherence to antiretroviral therapy.

J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;28(1):47-58.

doi:10.1097/00042560-200109010-00008

-

Kerse N, Buetow S, Mainous AG III, Young G, Coster G, Arroll B. Physician-patient relationship and medication compliance: a primary care investigation.

Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(5):455-461.

doi:10.1370/afm.139

-

Mainous AG III, Rooks BJ, Mercado ES, Carek PJ. Patient provider continuity and prostate specific antigen testing: impact of continuity on receipt of a non-recommended test.

Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:622541.

doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.622541

-

SteelFisher GK, Findling MG, Caporello HL, et al. Trust in US federal, state, and local public health agencies during COVID-19: responses and policy implications.

Health Aff (Millwood). 2023;42(3):328-337.

doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2022.01204

-

-

Suthar AB, Wang J, Seffren V, Wiegand RE, Griffing S, Zell E. Public health impact of COVID-19 vaccines in the US: observational study.

BMJ. 2022;377:e069317.

doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-069317

-

-

-

-

-

-

Mainous AG III, Xie Z, Dickmann SB, Medley JF, Hong YR. Documentation and treatment of obesity in primary care physician office visits: the role of the patient-physician relationship.

J Am Board Fam Med. 2023;36(2):325-332.

doi:10.3122/jabfm.2022.220297R1

-

Mainous AG III, Kelliher A, Warne D. Recruiting Indigenous patients into clinical trials: a circle of trust.

Ann Fam Med. 2023;21(1):54-56.

doi:10.1370/afm.2901

-

Thakur N, Lovinsky-Desir S, Appell D, et al. Enhancing recruitment and retention of minority populations for clinical research in pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine: an official American Thoracic Society research statement.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204(3):e26-e50.

doi:10.1164/rccm.202105-1210ST

There are no comments for this article.