Background and Objectives: Comprehensive sexual reproductive health care (SRH) in the United States, including abortion, is siloed from primary care, making it more difficult to access. The crisis in access has drastically worsened following the overturning of Roe v Wade, 410 US 113 (1973). Primary care clinicians (PCC) are well-positioned to protect and expand SRH access but do not receive sufficient training or support. The Reproductive Health Access Network (“Network”) was created to connect like-minded clinicians to engage in advocacy, training, and peer support to enhance access to SRH in their communities and practices. This evaluation explores PCC leaders’ experiences within this SRH organizing network.

Methods: In 2021, we conducted 34 semistructured phone interviews with a purposive sample of current (n=27) and former (n=7) PCC leaders in the Network (N=87). The program’s theory of change and network evaluation framework guided reflexive thematic analysis.

Results: Participants viewed Network support as critical to ending isolation through three mechanisms: connecting to a supportive community of like-minded peers, empowering leadership, and providing infrastructure for local organizing. They viewed mentorship as critical in building a sustainable and equitable pipeline of PCC leaders. Participants identified challenges to engaging fully, such as burnout and discrimination experienced both within and outside the Network.

Conclusions: Community-building, peer support, and mentorship are critical to building and sustaining PCC leadership in SRH-organizing communities. Efforts are needed to mitigate burnout, support SRH education and mentorship for PCCs, and transform into a truly inclusive community. The Network structure is promising for amplifying efforts to enhance SRH access through clinician leadership.

Early pregnancy loss, abortion, and contraception are essential and common sexual and reproductive health care (SRH) services that can be provided safely and effectively in outpatient and primary care settings. 1-4 Yet, these services are often difficult to access due to the historic siloing of SRH to specialty settings. 5, 6 Accessing SRH is more challenging for those with limited financial and social resources, especially those in Black, brown, and low-income communities that are most impacted by persistent health care inequities.7, 8, 9-14 The overturning of Roe v Wade in June 2022 via Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 597 US 215 (2022) and subsequent abortion bans across the United States have only worsened this access crisis.15-19

Primary care clinicians (PCCs), particularly family physicians and advanced practice clinicians (nurse practitioners, certified nurse-midwives, physician assistants), are well-positioned and trusted to improve SRH access in their communities. 2, 20-24 However, many PCCs do not receive adequate training or support to provide comprehensive SRH. Even among trained family physicians and advanced practice clinicians, few provide abortion or early pregnancy loss management in primary care due to institutional and structural barriers, including administrative resistance, lack of knowledge to navigate federal funding restrictions, stigma around provision, and state and federal regulations.4, 25-31 Professional associations, such as the Society of General Internal Medicine and the American Academy of Family Physicians, play important roles in setting scope of practice, providing clinical education, and representing PCCs’ priorities. However, these organizations historically have not prioritized proactive SRH advocacy and education.

In 2000, the Reproductive Health Access Project (RHAP) was founded in New York to train, support, and mobilize PCCs to ensure equitable access to SRH, including abortion. In response to challenges in accessing and providing SRH, RHAP’s Reproductive Health Access Network (“Network”) launched in 2007 to organize PCCs to protect and expand SRH nationally and in their localities and institutions. Beginning as a family physician-specific program, the Network expanded in 2012 to include PCCs broadly. As of 2023, the Network connects more than 7,700 clinicians from diverse personal and professional backgrounds and collaborates with reproductive health, rights, and justice organizations to advance the priorities of communities most impacted by barriers to SRH.32 The Network partners with SRH training and advocacy programs like Reproductive Health Education in Family Medicine, Medical Students for Choice, and others to build a community of like-minded clinicians. RHAP staff facilitate opportunities for Network members to connect, engage in clinical and leadership training, participate in advocacy, and receive peer support. The Network builds power among PCCs to integrate comprehensive SRH into primary care and clinical education, hold professional associations accountable for ensuring that SRH is an organizational priority, and engage in advocacy for policies and practices that improve reproductive autonomy.

While some studies have explored perspectives on SRH clinician advocacy, programs that build PCC leadership in SRH remain under-researched. 33-35 Therefore, we aimed to qualitatively explore the Network’s effectiveness in empowering clinicians to expand SRH access and to understand barriers and opportunities to strengthen the program’s ability to meet SRH needs. With 42 independent clinics forced to close in the first 5 months following the Dobbs decision, clearly, evidence-informed strategies to expand SRH access are urgently needed. 36 While this evaluation was conducted prior to the Dobbs decision and, therefore, does not reflect specific legal concerns that have emerged following the overturning of Roe, this study illuminates priorities and recommendations for improving clinician organizing, leadership, and advocacy to respond to ongoing inequities and threats to reproductive autonomy.

Program Description

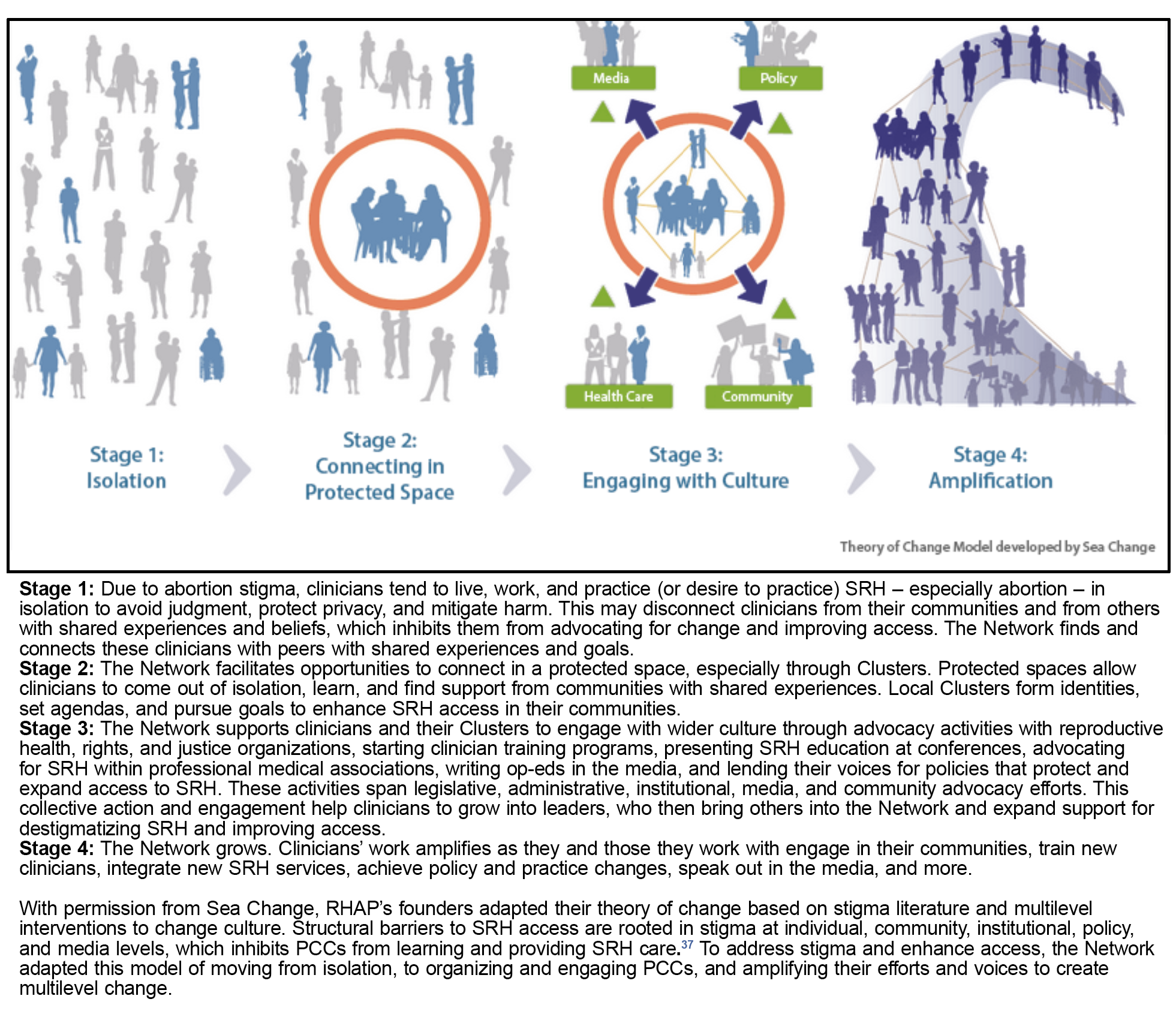

Figure 1 illustrates the Network’s theory of change to protect and expand SRH by training, supporting, and mobilizing PCCs.

Clinicians may join the Network by registering online, attending a RHAP-sponsored event, or being recommended by an existing member. All members are vetted to ensure safety. The Network’s clinicians are organized into “clusters,” state-based and professional chapters led by local clinician leaders: cluster leaders and professional association advocates (PAA). Cluster leaders represent various disciplines and lead clusters; PAAs are active in professional associations and amplify opportunities for their cluster. As of 2023, the Network has 27 clusters in 26 states, as well as three professional cohort clusters for advanced practice clinicians, internists, and emergency medicine. RHAP staff members provide cluster leaders and PAAs with leadership training, logistical support for recruitment and organizing, community partner connections, mentorship to empower leaders to develop and work toward goals, and stipends. Each cluster has one or two cluster leaders; each state-based cluster has one or two PAAs. Each cluster has an annual budget for events, education, and advocacy activities.

Sample and Data Collection

In 2021, we conducted a phenomenological qualitative evaluation, which seeks to uncover individuals’ lived experiences and how they understand those experiences.37 We conducted semistructured phone interviews to explore clinician leaders’ lived experiences in the Network, including how they believed the Network supported their leadership to engage in SRH advocacy. We interviewed current and former Network leaders, rather than general members, due to their high involvement with Network activities. We excluded current and former leaders who (a) entered their first formal Network leadership role within 3 months of initiating the study, (b) stepped down from their formal leadership role(s) more than 1 year prior, or (c) informed staff of their temporarily stepping away due to life circumstances. We identified 87 current and former leaders as eligible participants: 45 cluster leaders, 27 PAAs, and 20 former leaders (five held both cluster leader and PAA positions).

In June and July 2021, we emailed all 87 potential participants, with a reminder to nonresponders after 3 weeks. Thirty-eight (43.7%) agreed to interviews, but four canceled due to unexpected schedule conflicts and did not respond to our attempts to reschedule. The interview guide (Appendix A) was informed by the Network’s theory of change and the Center for Evaluation Innovation’s model for evaluating networks: connectivity, health, and results.38 Connectivity refers to participants’ relationships with one another, Network members, and partner organizations. Health includes the resources, staff, and infrastructure that sustain the program and the value these add to participants; results reflects the Network’s achievements. We queried on participants’ introduction to the Network, including stories of Network involvement and relationships (connectivity); journeys to leadership, resources, and infrastructure that supported leaders (health); and effects on participants’ practice, advocacy, and communities (results). These domains reflected participants’ movement through the theory of change.

At the beginning of each interview, interviewers described the study and obtained verbal consent. Demographics were collected through a self-reporting form before or after the interview. Demographic questions assessed the sample’s professional, racial, geographic, and income diversity because these characteristics reflect lived experiences brought to their Network involvement. Participants received a $50 check for their time. The team iteratively reflected on the interviewing process and determined that conceptual saturation (considering potential themes and balance in the proportion of cluster leaders, PAAs, and former leaders interviewed) was reached after 34 interviews. 39 So, recruitment ended. On average, interviews lasted 31.2 minutes (range: 20–52 min). The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, and transcripts were quality checked and anonymized by the interviewers. The Institutional Review Board of the Institute for Family Health deemed the study exempt from approval.

Analysis

We conducted reflexive thematic analysis using Braun and Clarke’s iterative, six-stage protocol.40 The analysis team independently read and annotated 15 to 20 transcripts and then discussed them to form an initial codebook of inductive and deductive codes informed by the theory of change and pillars of network evaluation. We hand-coded four identical transcripts to test the codebook, then met to discuss discrepancies and refine the codebook. Each team member then coded four to nine transcripts using Dedoose version 9.0.46 (SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC). After coding, the team met frequently to discuss excerpts and memos to identify themes. Excerpts were sorted into data matrices to facilitate analysis and depict interconnections between and across themes. After 2 weeks to consider the themes individually, the team met to validate results through discussion and to check results against data. 40

Reflexivity

Authors H.V.M. and S.S. conducted recruitment and interviews. H.V.M. was a public health graduate student and intern at RHAP. S.S. was a Master of Public Health-trained researcher and evaluator with experience in qualitative methods and a RHAP staff member. H.V.M. and S.S. did not work on the Network. Both had personal and professional backgrounds in expanding access to abortion through research, advocacy, and public health practice. Participants were aware of their interviewer’s positionality. S.S. did not interview anyone with whom she had prior working relationships.

All authors participated in coding and analysis. L.R., H.B.J., and L.T. worked directly with the Network and reviewed only anonymized transcripts to protect respondents’ privacy. H.B.J., L.R., and L.T. identified as organizers, advocates, and conspirators in the reproductive health, rights, and justice movements. Throughout all analysis stages, the team sent memos and conversed to practice reflexivity, acknowledging and mitigating the biases they brought to this evaluation as SRH professionals and RHAP staff.

We conducted 34 interviews with Network leaders. The majority (82.3%) were family physicians. Nearly one-third identified as Black, Indigenous, or Person of Color (28.1%). Table 1 depicts participants’ demographics.

|

Demographic

characteristics

|

n (%)

|

|

Identified as Black, Indigenous, or Person of Colora

|

9 (28.1)

|

|

Self-reported as low-income in childhood/adolescenceb

|

9 (26.5)

|

|

Network leader typec

|

|

Cluster leader

|

22 (64.7)

|

|

Professional association advocate

|

10 (29.4)

|

|

Former leader

|

7 (20.6)

|

|

Time in network

|

|

<2 years

|

3 (8.8)

|

|

2-5 years

|

20 (58.8)

|

|

6+ years

|

11 (32.4)

|

|

Geography

|

|

|

Northeast/mid-Atlantic

|

10 (29.4)

|

|

Southeast

|

5 (14.7)

|

|

Midwest

|

8 (23.5)

|

|

West

|

11 (32.3)

|

|

Primary clinical practice

|

|

Federally qualified health center or community health center

|

13 (38.2)

|

|

Hospital

|

6 (17.6)

|

|

Independent abortion clinic

|

3 (8.8)

|

|

Private practice

|

3 (8.8)

|

|

Other

|

9 (26.5)

|

Network Support of Clinicians’ Journeys and Leadership

Overall, participants described the Network as pulling them out of isolation into a journey of connectedness, engagement, and community involvement to enhance SRH access. The Network supported participants in three ways: connecting them with a supportive community of like-minded peers, empowering leadership, and providing infrastructure for local organizing. Table 2 illustrates themes with quotes from participants.

|

Theme

|

Excerpt #

|

Illustrative

quote

|

|

Connecting with a supportive community of like-minded peers that empowered leadership and offered solidarity, learning opportunities, and energy.

|

Excerpt 1

|

When you’re an abortion provider, you’re like an N of 1. There’s no abortion clinic that has more than one doctor there or one provider on any given day. That’s just how the work is done. (PAA)

|

|

Excerpt 2

|

[I feel] empowered to be out . . . as an abortion provider because that’s something I felt like I had to hide for a long time. Just having the support makes it a lot less stigmatized and scary . . . it gives me that inner sense it’s going to be okay. (Cluster leader & PAA)

|

|

Excerpt 3

|

I always knew about mife[pristone] as an option for [early pregnancy loss] . . . so I worked my butt off for almost 3 years trying to get the residency to obtain the mifepristone. . . . Being a part of [the Network] gave me resources because other people had done this ahead of me, so I had direct access to people who had gone through this process. (Cluster leader)

|

|

Excerpt 4

|

The text chain of the first year at [professional medical association conference] was five people, and now we have a WhatsApp of like a hundred people. So, it’s just—a hundred people isn’t one-on-one support and encouragement, but it’s a lot of support and encouragement. People walked into that [conference] space feeling unwelcome, but found each other and are finding a way to make it more welcoming. (Cluster leader & PAA)

|

|

Challenges to fully engaging within the Network and their communities centered on time, overcommitment, burnout, and power dynamics within and outside the Network.

|

Excerpt 5

|

We’ve done such incredible work in the state. I’m really proud of us; it’s just we’re all just tired. (Cluster leader & PAA)

|

|

Excerpt 6

|

I always feel like I’m not doing enough. I’m employed. I have three little kids. I have my partner. I’m constantly feeling like in everything in life I’m not doing enough. I just have to remind myself that showing up is enough and continuing even if you’re just chipping away at an iceberg, you’re still making progress. (Cluster leader)

|

|

Excerpt 7

|

I mean, that’s primary care . . . we’re over-committed. (Cluster leader)

|

|

Excerpt 8

|

There are people in this type of work who have many different outlooks on life. . . . It’s really important to make sure that people are somewhat on the same page because it lessens chances . . . for harmful dialogue. (Cluster leader)

|

|

Excerpt 9

|

The clinical connections of getting folks out and working and supporting them seems like the most feasible thing that we are set up to do, rather than changing the politics of the state. I think really being able to have the cluster identify its own needs, and listen to those [is important]. (Former leader)

|

|

The Network also served as a source of strength to navigate some external challenges, like power dynamics in the medical field.

|

Excerpt 10

|

When you’re working primarily with Ob/Gyns and . . . they make you feel like you don’t know what you're doing . . . It feels good to be like, ‘oh, well there’s a whole group of people who also do the same crazy thing.’ I am qualified to do this, I am trained to do this, and I’m part of a group of people who can back me up. (Cluster leader)

|

|

In reflecting on their pathways to leadership, participants felt that building mentorship ladders was a critical and sustainable strategy for building future leadership.

|

Excerpt 11

|

You’re making such a difference, not only for patients but for other learners too. It’s full circle. . . . I’m now covering an [abortion clinic] that is really close to where I went to medical school. . . . Now I’m on the other side . . . trying to help other people who are interested. (Cluster leader & PAA)

|

|

Excerpt 12

|

I got to be a national lecturer because . . . this amazing system of . . . teach one and then reach back and grab somebody else and pull them in. They teach one with you, [and] now they can teach one by themselves or . . . pull somebody in who hasn’t taught before. . . This concept that good mentorship means you never present alone, you always reach back, you always try to get someone else in the group for that speaking opportunity or a writing opportunity. . . It just feels very supportive and empowering. (Former leader)

|

They discussed providing SRH as isolating work (Excerpt 1, Table 2). Participants came to the Network feeling like the sole SRH provider and/or advocate in their community, while experiencing the burdens of working in an environment constantly under threat. However, participants expressed how becoming "part of a community of like-minded, enthusiastic, engaged individuals, all fighting for this cause, gave them resources, solidarity, and strength to break through isolation and engage confidently in their communities" (Excerpt 2). While the sense of isolation never completely disappeared, the Network provided a community of support. And the peer-support infrastructure connected participants to informal mentors who engaged in similar advocacy to which they aspired (Excerpt 3).

The community offered participants "solidarity," opportunities for "learning," the "fire" to create change, and the capacity to amplify efforts by mentoring others to do the same. Similarly, PAA participants shared how the Network community and peer support empowered them to elevate SRH education, training, and provision as core components of primary care through professional association engagement (Excerpt 4).

The Network provided infrastructure to enable advocacy in participants’ communities. Participants valued the staff’s provision of mentorship, stipends, and logistical support, which enabled clusters to partner, learn, and engage with grassroots organizations, policymakers, and media. For example, one participant discussed the Network’s support in developing a partnership between the cluster and a state advocacy coalition that resulted in “a power hour . . . to expose the fact of [stores] hiding emergency contraception behind the pharmacy counter, rather than having it at the consumer level on the shelf” (Cluster leader & PAA). Another described starting a coalition that the Network “helped us sponsor . . . to bring at least 30 different organizations . . . to figure out how to protect abortion access in our state, [and] other reproductive needs” (Cluster leader). Participants viewed Network support as critical to moving them out of isolation and into leadership and advocacy opportunities.

Challenges to Network Engagement

Participants also identified challenges to fully engaging within the Network and their communities. They named "time to be really engaged" as a major limiting factor that contributed to burnout. They pointed to having busy schedules, being "over-committed" with "competing interests professionally and personally," and just being "tired" (Excerpts 5, 6, 7). Burnout was further exacerbated by external challenges, like stigma and ongoing fights for "human rights and social justice." While all shared time and energy-related barriers, those living in states with greater abortion restrictions more frequently commented on external challenges.

Participants of color and advanced practice clinicians reflected on interpersonal and structural tensions and discrimination. As the Network grew beyond its founding group of family physicians, a new mix of perspectives and identities clashed with long-standing power dynamics. Some discussed a "sense of not belonging." They felt othered in these White and "woman/female-language-heavy" spaces that implicitly excluded Black, Indigenous, People of Color, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender clinicians. One participant described the need for values clarification to connect the community and prevent further interpersonal harm (Excerpt 8).

Similarly, tensions emerged around decisions about Network organizing strategies. Long-term leaders often lived in East- and West-coast cities and projected strategies well-suited for liberal urban settings but that were not attuned to the nuances of newer leaders’ more conservative communities in the country’s interior. These groups disagreed with the Network’s deep focus on abortion at the time, rather than on SRH broadly. Newest leaders described the need to understand local priorities (Excerpt 9).

Institutional power dynamics in medicine also perpetuated othering across clinician disciplines. For example, family physician participants reflected on feeling marginalized by false perceptions that they were not skilled enough to provide SRH compared to Ob/Gyns. Yet, participants noted peer support as a source of strength to navigate these challenges (Excerpt 10). Some, including physicians, commented on perceptions of bias toward physicians within the Network:

There has always been . . . a bias toward MDs. . . The way in which things are pursued and also some of the opportunities . . . are sometimes only available for MDs, and sometimes their language isn’t inclusive for all health care providers. . . It would be nice if they explicitly welcomed all primary care health providers. . . I think everybody would feel more included and welcome. And, we’d end up with a group that was more reflective of who’s providing the care—all of these people.

Despite the frustration, participants appreciated Network staff working to make the community a more "welcoming space" for all primary care professions, perspectives, and backgrounds. They cited the Network’s alignment with their values as crucial for keeping them connected.

Pathways to Leadership

Several participants noted that they became Network leaders by being “voluntold” by former leaders. Some reported conflicting feelings about this, citing it as a push they needed to build confidence and a potential contributor to burnout:

I was at the point where I was thinking about stepping back from my roles in my state academy and [former leader] was like, “Nope, now is the time you put your time in. Now you need to do something more and . . . use the momentum.” So, [they were] kind of the encouragement I needed.

Participants recognized that they could not remain in leadership indefinitely and reflected on mentorship ladders as a strategy to build sustainable leadership. Participants described their experiences as mentees receiving support in teaching, advocacy, and networking. They continued the cycle by becoming mentors and supporting others (Excerpt 11). They pointed to clinician trainees as future potential leaders and asserted the importance of incorporating more trainees into Network activities (Excerpt 12). By maintaining a mentorship ladder and helping trainees grow into Network leaders, they could sustain and positively impact the community and movement.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This evaluation explored the ways in which PCC leaders engaged in an organized community for SRH access. Participants reported journeys consistent with the theory of change, progressing from isolation to connection, engagement, and empowerment that drives amplification of efforts to address SRH access barriers. They viewed Network support as critical to moving them out of isolation and into leadership and active engagement in their communities.

Community-building and peer support were key in developing leadership and sustaining Network engagement. Studies on clinician advocacy in SRH similarly have concluded that community-building is critical due to its role in providing emotional support, information, motivation, and strength.33, 35 Our findings on the importance of peer support and community became even more critical after Dobbs, as antiabortion protesters and politicians have grown emboldened to further undermine SRH and attack those who advocate for or provide abortion.19 The hostility and uncertainty amplified by Dobbs may contribute further to clinician burnout, pointing to the need for a strong and sustainable community that provides motivation and resources, assists in setting boundaries, and shares in the physical and emotional burdens of this work to ultimately enhance leaders’ resiliency. 35, 41-44

Furthermore, participants shared experiences of tension and discrimination within the Network, which may reflect structural discrimination and power in the medical system and reproductive health and rights movements.45, 46, 47, 48, 49 The Network had a history of hand-selecting future leaders through personal connections, which limited its ability to develop diverse, inclusive leadership that enables innovation and problem-solving and reflects the lived experiences of patient communities.50 Therefore, the Network has prioritized integrating a reproductive justice approach into its work by centering the expertise of communities most impacted by barriers to SRH, formalizing processes to meaningfully recruit diverse clinician leadership, and participating in grassroots coalitions that have long been organizing for structural change.47, 51, 52 Each component is crucial for dismantling harm and meeting the SRH needs of underserved communities.53-55 However, ongoing work within the Network and within reproductive health and rights movements is needed to transform into a community that is truly inclusive.

Our study had several limitations. The sample included only Network leaders, not the entire membership. Therefore, we did not hear from less engaged individuals who may have had different perceptions. As such, findings may not be generalizable to all clinicians or informal leaders. Participation bias was possible because interviewees may have self-selected to deeply engage and consent to interviews. Although participants were unfamiliar with the interviewers, some may have felt pressured to share positive experiences and minimize negative ones due to their ongoing involvement with the Network. Furthermore, our study took place prior to the Dobbs decision, which has significantly altered the abortion access landscape and clinicians’ abilities to legally provide comprehensive SRH in many states.16 Participants are likely experiencing novel challenges as a result. Future evaluations should assess ongoing interpersonal and structural challenges and how support for leaders has adapted to respond to the increasingly tumultuous environment. Strengths of our study included our rigorous and iterative qualitative analysis with frequent and intentional reflexivity. We explored a unique, under-researched phenomenon of PCC leadership and organizing for SRH.

These findings indicate a critical need to strengthen clinician organizing for SRH access by dedicating resources to peer support and community-building, leadership and advocacy training, and mentorship. As access to comprehensive SRH further wanes following Dobbs, we must develop novel, evidence-based strategies for mitigating the resulting harm. The Network structure is promising for amplifying efforts to enhance SRH access through clinician leadership.

Financial Support

The Reproductive Health Access Network is grant-funded by an anonymous donor. The funding source was not involved in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit this article for publication.

Presentations

The content of this manuscript was presented as an oral virtual presentation for the American Public Health Association’s Annual Meeting in November 2021.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the work of the Reproductive Health Access Project staff to manage, grow, and sustain the Network, as well as the efforts of all clinicians representing members and leaders within the Network.

References

-

Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Board on Health Care Services; Committee on Reproductive Health Services: Assessing the Safety and Quality of Abortion Care in the U.S.

The Safety and Quality of Abortion Care in the United States. National Academies Press; 2018.

doi:10.17226/24950

-

Summit AK, Casey LMJ, Bennett AH, Karasz A, Gold M. “I don’t want to go anywhere else”: patient experiences of abortion in family medicine. Fam Med. 2016;48(1):30-34.

-

Beaman J, Schillinger D. Responding to evolving abortion regulations: the critical role of primary care.

N Engl J Med. 2019;380(18):e30.

doi:10.1056/NEJMp1903572

-

Dennis A, Fuentes L, Douglas-Durham E, Grossman D. Barriers to and facilitators of moving miscarriage management out of the operating room.

Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2015;47(3):141-149.

doi:10.1363/47e4315

-

Jones RK, Witwer E, Jerman J.

Abortion Incidence and Service Availability in the United States, 2017. Guttmacher Institute; 2019. Accessed November 16, 2022.

doi:10.1363/2019.30760

-

-

Roberts DE. Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty. Vintage Books; 2017.

-

Nosek MA, Simmons DK. Sexual and reproductive health disparities experienced by people with disabilities: myth versus reality.

Californian J Health Promot. 2007;5(SI):68-81.

doi:10.32398/cjhp.v5iSI.1201

-

Prather C, Fuller TR, Marshall KJ, Jeffries WL IV. The impact of racism on the sexual and reproductive health of African American women.

J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2016;25(7):664-671.

doi:10.1089/jwh.2015.5637

-

Sutton MY, Anachebe NF, Lee R, Skanes H. Racial and ethnic disparities in reproductive health services and outcomes, 2020.

Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137(2):225-233.

doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004224

-

Hall KS, Moreau C, Trussell J. Determinants of and disparities in reproductive health service use among adolescent and young adult women in the United States, 2002-2008.

Am J Public Health. 2012;102(2):359-367.

doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300380

-

-

Everett BG, McCabe KF, Hughes TL. Sexual orientation disparities in mistimed and unwanted pregnancy among adult women.

Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2017;49(3):157-165.

doi:10.1363/psrh.12032

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Grumbach K, Hart LG, Mertz E, Coffman J, Palazzo L. Who is caring for the underserved? A comparison of primary care physicians and nonphysician clinicians in California and Washington.

Ann Fam Med. 2003;1(2):97-104.

doi:10.1370/afm.49

-

-

-

Logsdon MB, Handler A, Godfrey EM. Women’s preferences for the location of abortion services: a pilot study in two Chicago clinics.

Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(1):212-216.

doi:10.1007/s10995-010-0722-4

-

Godfrey EM, Rubin SE, Smith EJ, Khare MM, Gold M. Women’s preference for receiving abortion in primary care settings.

J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19(3):547-553.

doi:10.1089/jwh.2009.1454

-

Srinivasulu S, Yavari R, Brubaker L, Riker L, Prine L, Rubin SE. US clinicians’ perspectives on how mifepristone regulations affect access to medication abortion and early pregnancy loss care in primary care.

Contraception. 2021;104(1):92-97.

doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2021.04.017

-

Razon N, Wulf S, Perez C, et al. Family physicians’ barriers and facilitators in incorporating medication abortion.

J Am Board Fam Med. 2022;35(3):579-587.

doi:10.3122/jabfm.2022.03.210266

-

Srinivasulu S, Maldonado L, Prine L, Rubin SE. Intention to provide abortion upon completing family medicine residency and subsequent abortion provision: a 5-year follow-up survey.

Contraception. 2019;100(3):188-192.

doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2019.05.011

-

deFiebre G, Srinivasulu S, Maldonado L, Romero D, Prine L, Rubin SE. Barriers and enablers to family physicians’ provision of early pregnancy loss management in the United States.

Womens Health Issues. 2021;31(1):57-64.

doi:10.1016/j.whi.2020.07.003

-

-

Stulberg DB, Monast K, Dahlquist IH, Palmer K. Provision of abortion and other reproductive health services among former Midwest Access Project trainees.

Contraception. 2018;97(4):341-345.

doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.01.002

-

Summit AK, Lague I, Dettmann M, Gold M. Barriers to and enablers of abortion provision for family physicians trained in abortion during residency.

Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2020;52(3):151-159.

doi:10.1363/psrh.12154

-

-

Carroll S, Joshi D, Espey E. Physicians and healthcare professionals as advocates for abortion care and reproductive choice.

Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2022;34(6):367-372.

doi:10.1097/GCO.0000000000000833

-

Joffe CE, Weitz TA, Stacey CL. Uneasy allies: pro-choice physicians, feminist health activists and the struggle for abortion rights.

Sociol Health Illn. 2004;26(6):775-796.

doi:10.1111/j.0141-9889.2004.00418.x

-

Manze M, Romero D, Kwan A, Ellsworth TR, Jones H. Physician perspectives of abortion advocacy: findings from a mixed-methods study.

BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2023;49(1):7-11.

doi:10.1136/bmjsrh-2021-201394

-

-

Ritchie J, ed. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. Vol 2. Sage; 2014.

-

-

Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, Marconi VC. Code Saturation versus meaning saturation: how many interviews are enough?

Qual Health Res. 2017;27(4):591-608.

doi:10.1177/1049732316665344

-

Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis?

Qual Res Psychol. 2021;18(3):328-352.

doi:10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

-

Grant A. In the company of givers and takers. Harv Bus Rev. 2013;91(4):90-97,142.

-

Ruisoto P, Ramírez MR, García PA, Paladines-Costa B, Vaca SL, Clemente-Suárez VJ. Social support mediates the effect of burnout on health in health care professionals.

Front Psychol. 2021;11:623587.

doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.623587

-

Murayama H, Nonaka K, Hasebe M, Fujiwara Y. Workplace and community social capital and burnout among professionals of health and welfare services for the seniors: A multilevel analysis in Japan.

J Occup Health. 2020;62(1):e12177.

doi:10.1002/1348-9585.12177

-

-

Dimant OE, Cook TE, Greene RE, Radix AE. Experiences of transgender and gender nonbinary medical students and physicians.

Transgend Health. 2019;4(1):209-216.

doi:10.1089/trgh.2019.0021

-

Loftin C, Newman SD, Dumas BP, Gilden G, Bond ML. Perceived barriers to success for minority nursing students: an integrative review.

ISRN Nurs. 2012;806543.

doi:10.5402/2012/806543

-

Ross L, ed. Radical Reproductive Justice: Foundations, Theory, Practice, Critique. The Feminist Press at The City University of New York; 2017.

-

Serafini K, Coyer C, Brown Speights J, et al. Racism as experienced by physicians of color in the health care setting.

Fam Med. 2020;52(4):282-287.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.384384

-

Odom KL, Roberts LM, Johnson RL, Cooper LA. Exploring obstacles to and opportunities for professional success among ethnic minority medical students.

Acad Med. 2007;82(2):146-153.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31802d8f2c

-

Page S.

The Difference: How the Power of Diversity Creates Better Groups, Firms, Schools, and Societies. Rev. ed

. Princeton University Press; 2008.

doi:10.1515/9781400830282

-

Wilbur K, Snyder C, Essary AC, Reddy S, Will KK, Saxon M. Developing workforce diversity in the health professions: a social justice perspective.

Health Prof Educ. 2020;6(2):222-229.

doi:10.1016/j.hpe.2020.01.002

-

-

Karani R, Varpio L, May W, et al. Commentary: racism and bias in health professions education: how educators, faculty developers, and researchers can make a difference.

Acad Med. 2017;92(11S):S1-S6.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001928

-

Gilliam ML, Neustadt A, Gordon R. A call to incorporate a reproductive justice agenda into reproductive health clinical practice and policy.

Contraception. 2009;79(4):243-246.

doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2008.12.004

There are no comments for this article.