Background and Objectives: A significant portion of medical education takes place in primary care settings with family medicine clinician teachers that have variable backgrounds in teaching. Ernest Boyer’s concept of education scholarship calls on faculty to systematically study and innovate their teaching practices. This meta-ethnographic review synthesizes the literature on primary care clinician teachers’ perspectives and experiences of integrating education scholarship in practice.

Methods: We conducted an electronic database search in PubMed/Medline, Scopus, ERIC, and Web of Science for primary research articles published between January 2000 and August 2021. In the included articles, researchers studied primary care physicians’ and/or residents’ perspectives of clinical teaching and reported qualitative results (eg, interviews, focus groups). Of the 1,454 articles found in the search, we included 33 in the final synthesis. We used line-by-line descriptive coding of the qualitative data to develop analytical themes.

Results: Four main themes emerged from our synthesis: (1) perceptions of clinical teaching (lack of confidence, presumed teaching competency, lack of formal recognition); (2) clinical teaching strategies (learner-centered teaching, ad hoc teaching, role modeling, mentorship); (3) benefits of clinical teaching (shared learning experience, networking, personal interest, career satisfaction); and (4) challenges of clinical teaching (inadequate time, compensation, conflicting responsibilities).

Conclusions: Clinician teachers identified several common factors regarding their scholarly roles but had difficulty describing them in relation to education scholarship. Institutional support, resources, and awareness are needed to assist family medicine clinician teachers to further implement Boyer’s concept of education scholarship in practice—specifically, to study, evaluate, and innovate current clinical teaching strategies.

Family medicine physicians play critical community-based roles in providing and coordinating interdisciplinary care, health promotion, and patient advocacy. Many also take on additional scholarly responsibilities, such as teaching, mentorship, and research. In fact, scholarship is formally recognized as a significant component of family physicians’ core professional competencies. 1, 2 This strength is acknowledged in the Four Pillars for the Primary Care Physician Workforce model proposed by the Council of Academic Family Medicine (CAFM) and since adopted by the broader primary care community. 3-5

In 1990 Ernest Boyer introduced a model elaborating on the traditional meaning of scholarship—a model that goes beyond the usual primary focus on research and publication. 6, 7 Boyer suggested that scholarship involves actively engaging with one’s work, considering it in broader contexts, and going beyond the basic duties of a faculty member. He proposed four key domains (Table 1): the scholarship of discovery (formal research), integration, application, and teaching (education scholarship). 6 The scholarship of teaching challenges the historical view that teaching is a priority secondary to research and publication, or something that is done as an adjunct to research and publication. In this model, teaching is described as a scholarly enterprise: carefully planned, continuously examined, and involving the transformation of teaching practices to stimulate active learning. 6, 7

|

Domain

|

Description

|

|

Scholarship of discovery

|

To build new knowledge through traditional peer-reviewed research

What is to be known and what is yet to be found?

Examples: Peer-reviewed publishing, producing new knowledge

|

|

Scholarship of integration

|

To interpret knowledge produced by original research, make connections across the disciplines, and synthesize the knowledge in a broader context

What do the findings mean?

Examples: Literature review, writing a textbook

|

|

Scholarship of application

|

To apply theory to practice, and service to the needs of the community

How can knowledge be responsibly applied to consequential problems?

How can it be helpful to individuals as well as institutions?

Examples: Consulting, assuming leadership roles

|

|

Scholarship of teaching

|

To communicate knowledge to others while also transforming and extending teaching practices in order to achieve optimal learning

To mentor others and preserve the continuity of knowledge

To systematically study the teaching and learning processes

Examples: Research in education and learning theory, curriculum development, design and development of instructional material

|

A significant portion of undergraduate medical education as well as primary care residency programs takes place in primary care settings. Accordingly, much of the teaching responsibility falls on faculty primarily trained as family medicine clinicians. While these clinicians take on acknowledged academic teaching roles, their backgrounds in clinical education can vary widely from introductory faculty development to a formal postgraduate degree. 8 Medical schools are accountable to rigorous accreditation standards, and the influence of clinician teachers on learners is important to recognize. These clinician teachers embody the delivery of the formal (eg, lectures), informal (eg, ad hoc clinical teaching), and hidden (eg, role-modeling and mentorship) curricula. High-quality teaching by clinical faculty in family medicine is critical to the success of medical students and to the legitimacy of associated institutions. 9, 10

While scholarship and teaching as core competencies in family medicine are well documented in the literature, understanding how clinician teachers integrate education scholarship in practice is not. We asked this research question: What are the experiences of primary care physicians regarding clinical teaching, and how do their practices relate to education scholarship based on Boyer’s definition? Our review aims to provide a fuller understanding of the qualitative literature on the key facilitators, barriers, and experiences of primary care physicians’ implementation of education scholarship in their clinical teaching practices.

We based our study on the premise that we would find applied grounded theory in medical education in the perceptions and activities described by primary care clinical educators. 11 We conducted a qualitative data synthesis using a meta-ethnographic approach. This interpretive method involves comparison of primary studies to obtain a clearer theoretical understanding of a particular phenomenon. The final objective of a meta-ethnography is to develop novel interpretations and conceptual insights based on the primary data. 12 The method involves a literature search, abstract selection, quality appraisal, data extraction, and synthesis of key concepts and themes. 13, 14 The research team consisted of a family medicine physician and clinical teacher, an education scientist, and a medical student.

Search Protocol

We conducted an electronic database search to identify primary qualitative studies involving primary care clinician teachers. Developed with guidance from an education librarian, the search strategy captured four main search concepts: primary care, clinician teachers, professional competencies, and qualitative research (Appendix 1). The overlap of these four concepts best describes our area of focus for this synthesis. In August 2020, one reviewer (L.L.) searched the following databases: PubMed/Medline, Scopus, ERIC, and Web of Science. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and text word synonyms were used with Boolean operators to combine the four main search concepts.

Selection of Eligible Studies

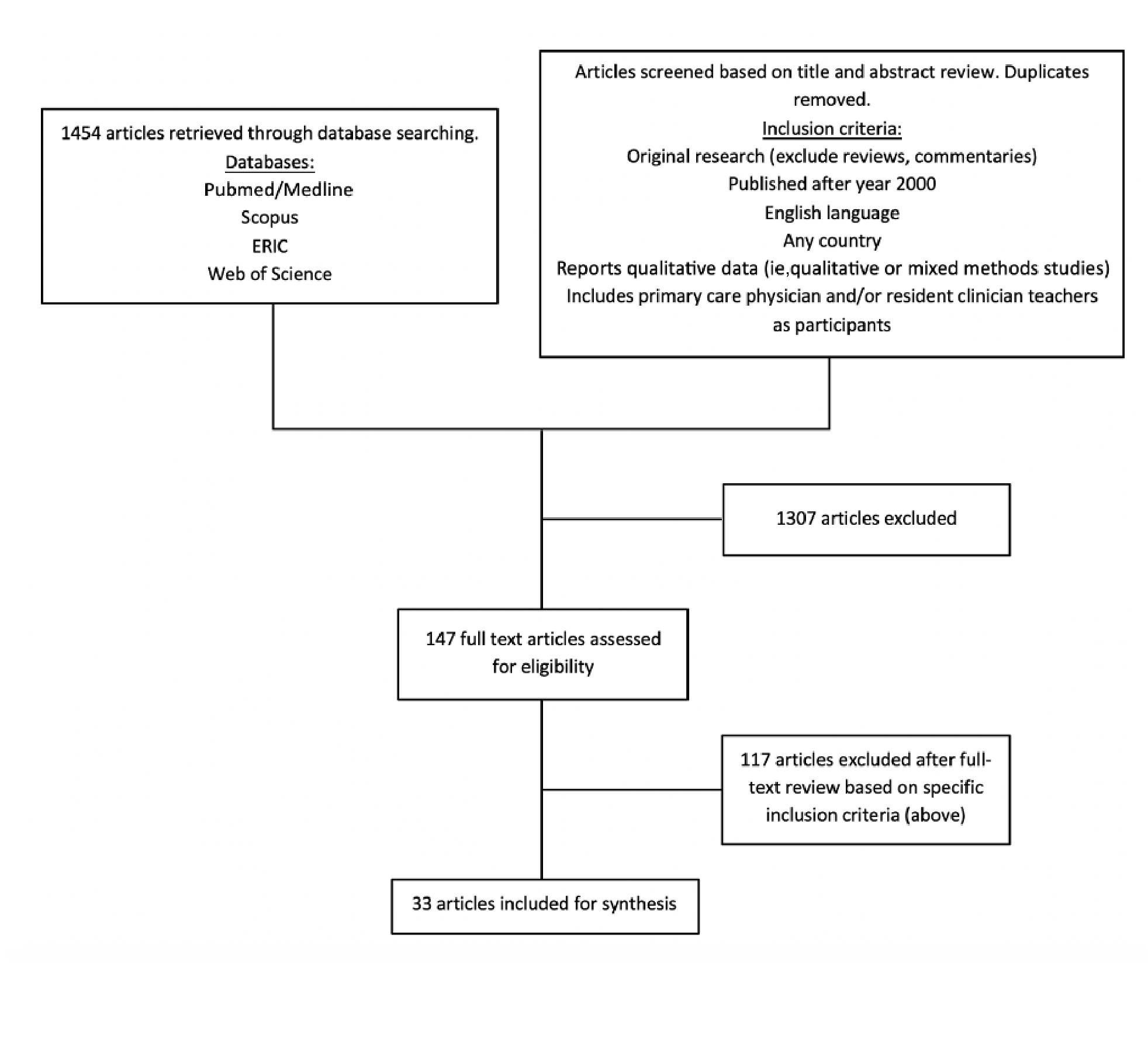

One reviewer (L.L.) screened the retrieved abstracts for relevance. Then the full article texts of selected abstracts were retrieved and reviewed (by L.L.) for potential inclusion based on specific criteria (Figure 1). Articles with the following key concepts were included: primary care (family medicine, community pediatrics, ambulatory internal medicine) physicians and residents, and perspectives on clinician teacher roles. Due to the subjective, experiential nature of our study objective, we focused on studies reporting qualitative results.

We excluded articles if they lacked qualitative results, were not original research (ie, reviews, commentaries), unavailable in full text articles (eg, conference abstracts), or focused on other health care professions, medical student perspectives, or topics other than clinical teaching in primary care. We lacked capacity to assess non-English articles. We searched literature published after the year 2000, 10 years after Boyer proposed his concept of education scholarship, 6 to allow time for dissemination, acceptance, and possible implementation of his concept. A total of 1,454 articles were retrieved in the initial search in 2020, of which 30 met inclusion criteria. The search was repeated in 2021, resulting in three additional articles. Ultimately, 33 articles were retained for inclusion in the synthesis (Figure 1 ).

Data Extraction and Critical Appraisal

Data extraction and critical appraisal of full text articles were done by two reviewers (L.L. and B.C.) independently. We used the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool for qualitative studies to evaluate the quality of the included studies. We chose the CASP tool because it provided a systematic process for critical appraisal and focused on assessing the study validity and relevance of the results to our study questions. One reviewer (L.L.) used the CASP tool to evaluate the quality of each selected study. No articles adhering to the inclusion criteria were rejected based on the CASP tool. 15

Data were extracted using a data extraction tool we developed based on the Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group guidelines. We piloted the tool on five articles, and we discussed discrepancies among reviewers until consensus was reached. 16 The following information was extracted from each article: bibliographic information, study objectives, design and data collection methods, sample size, participant characteristics, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and qualitative data. We extracted primary data, as well as the primary studies authors’ conceptual interpretations, in the synthesis because the latter offered additional descriptive and conceptually rich data relevant to the aim of our synthesis.

Our thematic analysis involved inductive coding of the primary study concepts and comparison of the codes across articles. We used codes generated from previously reviewed articles to aid in the extraction of similar codes. Related codes were organized into groups to generate overarching themes. To preserve the structure and context of the qualitative data, data were extracted verbatim. Qualitative data were considered to be study findings as well as all text labeled as “results” or “findings.” 17 Discrepancies related to coding and theme generation were resolved through team discussion until reaching consensus. The diversity of the research team enabled potential alternative interpretations in the synthesis of the aggregated results.

We compared themes and concepts across articles. We found similarity across article themes, and no contradictory concepts were identified in our synthesis. We did not conduct a refutational synthesis because no concepts were strongly contested across papers.

Characteristics of Included Studies

A total of 33 articles were included. About half were conducted in North America (33.3% United States [n=11], 15.2% Canada [n=5]), 18.2% in the United Kingdom (n=6), 15.2% in Africa (n=5), and 18.1% in other countries (Asia, Australia, New Zealand, Sweden, South America [n=6]). The majority (69.7% [n=23]) used semistructured interviews for data collection. Focus groups were used in 18.2% (n=6) and qualitative questionnaires in 12.1% (n=4).

Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 display the four main themes from the synthesis and illustrate selected narrative data from both the primary study authors and participants. Table 2 illustrates the themes that represented a commonality among multiple articles. The majority of articles studied the perspectives of attending primary care physicians, with only a minority focused on residents. Themes pertaining to attending and resident clinician teachers were similar, with one exception. Residents felt they had additional responsibilities (eg, exams) and were formally evaluated on their teaching performance.

|

Perceptions of clinical teaching

|

|

Theme and subthemes

|

References

|

Illustrative quotes

|

|

Teaching is a skill to be continuously developed.

|

18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29,

30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39

|

Researcher comments “One participant noted how formalized training programs might improve their teaching and scholarship skills in medical education, ‘If I got some more formal training, I can take this skill to the next level. I can make it more rigorous.’” (Triemstra 2020) 40 “Learning to teach was described as a dynamic and evolving process influenced by multiple life experiences.” (Hartford 2017) 23 “Preceptors wanted to become more successful, innovative teachers. They also desired to learn how to improve their efficiency and how to use students effectively in actual clinical settings.” (Paul 2020) 31 “Participants reported a desire for formal training and wanted to learn how to be more aware of themselves as role models, give appropriate feedback, and motivate students.” (Sternszus 2016) 36

|

|

Lack of confidence in teaching

|

18, 20, 22, 23, 24,

26, 27, 29, 41, 30, 33, 34, 35, 37, 40, 38

|

Researcher comments “Trainers worried about the ability of [residents] to teach effectively, often citing their lack of training in teaching.” (Harrison 2019) 22 “They [clinician teachers] also describe how insecure they feel, and how they feel the need to have more teaching tools.” (Moore 2020) 41 Participant quotes “Have I learned enough? Feels like I could use at least another year of residency before teaching.” (Lin 2018) 29 “I think that we are all learning, I mean we all do the best we can, basically using our intuition, but really I don’t have the skills yet.” (Moore 2020) 41

|

|

Competence in clinical teaching is often presumed by institution.

|

19, 23, 26, 27, 41, 33, 40

|

Researcher comments “The respondents thought that the medical school was not really recognising the magnitude of what it was asking of them and was not offering them support to do the job.” (Blitz 2018) 20 “These institutional characteristics were felt to perpetuate a ‘presumption of competence’ that doctors are inherently good (or ‘good enough’) teachers.” (Larson 2017) 27 Participant quotes “They (university academics) come to your door and say ‘Can you just have this person with you?’ . . . I like to have the objectives beforehand, but they don’t respond or don’t tell me, so I feel uncomfortable.” (Moore 2020) 41 “One educator noted that a supervisor had observed, ‘We need someone to do this . . . you look like a good person [to take on the role of clinician teacher].’” (Triemstra 2020) 40

|

|

Lack of formal recognition and perceived value in teaching (eg, compared to conducting research)

|

19, 20, 21,

26, 27, 29, 31

|

Researcher comments “Participants expressed frustrations with lack of incentives mainly on career path and recognition.” (Besigye 2019) 19 “Rejection of the ‘presumption of competence’ belief is required by individuals and institutional or professional licensing bodies. There should be respect for teaching as an important skill set distinct from clinical acumen.” (Larson 2017) 26 “[Participants] expressed concern that teaching competency was not emphasized or valued highly at their institution.” (Larson 2017) 27 “Preceptors expressed concerns over a lack of recognition or acknowledgment of their efforts. Whether compensation consisted of financial gain or continuing medical education credits, most preceptors thought that these factors were insufficient to overcome the financial and time realities in their clinic.” (Paul 2020) 31

|

|

Clinical teaching strategies

|

|

Theme and subthemes

|

References

|

Illustrative quotes

|

|

Clinician teachers focus on learner-centered teaching.

|

20, 23, 24, 30, 31, 33, 42, 43, 37, 38, 44

|

Researcher comments “Exploration of learners’ needs versus rigidity of teaching.” (Morrison 2005) 30 “Many supervisors attempt to ‘tailor’ the time in general practice to the trainees’ interests, helping them to get the most out of the time, with clear appreciation of trainees’ motivations and needs.” (Sabey 2015) 33 “Physicians try to adapt their teaching to the learner’s level of knowledge, what they believe they need to know, and a way of communicating that suits each learner.” (Stenfors-Hayes 2015) 43

|

|

The clinician teacher is the coordinator of the learning environment.

|

18, 20, 22, 23, 45,

31, 32, 33, 42, 43, 44

|

Researcher comments “Trainers expressed a sense of personal responsibility and accountability for the quality of teaching provided to medical student teaching.” (Harrison 2019) 22 “The majority of medical teachers referred to the importance of creating learning environments in which trainees felt comfortable and safe to answer questions.” (Hartford 2017) 23 “The teaching and learning environment was key and this was shaped by enthusiastic teachers.” (Jones 2020) 45 Participant quotes “I think the teacher sets the framework in which that person can experiment and learn safely.” (Blitz 2018) 20

|

|

Informal ad hoc teaching is valued.

|

18, 20, 23, 33, 42, 37

|

Researcher comments “Access to immediate advice through ad hoc supervision encounters was important to ensure questions could be addressed and that registrars felt supported and confident.” (Morrison 2015) 46 “The immediacy of ad hoc encounters provided the information that the [resident] needed at that moment to progress patient care. This way, immediacy supported safety and education.” (Morrison 2015) 46 Participant quotes “It’s quite informal . . . there are different places I teach, so I’ll teach them on the ward, at the bedside. I think that’s the best learning experiential.” (Hartford 2017) 23

|

|

Diversity in clinical teaching techniques is valued.

|

18, 23, 28, 41, 30, 33, 42, 34, 43, 44, 39

|

Researcher comments “The use of interactive skills such as small group techniques, audience participation techniques, including participant feedback in teaching, using a range of teachings aids . . . in clinical teaching were reported widely.” (de Villiers 2014) 38 “They teach using common sense, intuition and by being flexible in the way they teach. They try different ways to motivate the students and to create a good teaching atmosphere.” (Moore 2020) 41 Participant quotes “Teaching trainees [is] context and environment dependent, case based, and patient orientated.” (Hartford 2017) 23 “I think it’s just adding to your [education] toolkit, so you have more things that you can go and grab and say, I’m going to use this here, use that there.” (Zipkin 2020) 39 “Engaging in those mentorship and teaching programs earlier in my career was about competency and versatility with the learner in front of me.” (Zipkin 2020) 39

|

|

Role modeling and informal mentorship are important parts of the student-teacher relationship.

|

18, 20, 23, 25, 45, 26, 27, 29, 41, 30, 46, 31,

33, 42, 34, 43, 36, 37, 44

|

Researcher comments “Informants described the importance of being a mentor as well as an educator in order to impact the learner in areas such as skills and attitudes.” (Larson 2017) 26 “They seemed to learn about role modeling in an implicit fashion, simply by watching their attending physicians and residents perform.” (Sternszus 2016) 36 “With trainees, the physicians also role model both as a person and as a professional, with the role modeling being both explicit and implicit.” (Stenfors-Hayes 2015) 43

|

|

Near-peer teaching and mentorship with resident teachers is valued.

|

25, 45, 30, 34, 36, 37

|

Researcher comments “All residents reported the experience of near-peer teaching as primarily a positive one.” (Ince-Cushman 2015) 25 “Near peer teaching was felt to confer advantages with [residents] having experiences and learning agendas closely aligned with students, leading to student-centered teaching. [Residents] did this by having a non-hierarchical learning environment meeting students’ learning agendas.” (Jones 2020) 45 “Learning was potentially improved through social and cognitive congruence between the learners and learner-teacher.” (Silberberg 2013) 34 “Registrars considered they were more in tune with what medical students needed to know, and medical students reported feeling more comfortable with people closer to themselves in age.” (Silberberg 2013) 34

|

|

Benefits of clinical teaching

|

|

Theme and subthemes

|

References

|

Illustrative quotes

|

|

Clinical teaching can be a shared learning experience.

|

18, 20, 23,

47, 25, 45, 30,

32, 33, 42, 34, 43, 44

|

Researcher comments “Clinicians enjoyed the intellectual exercise of having students with them, expressing enjoyment at being challenged and having the opportunity to update their knowledge (either with information from students, or from being provoked into checking on latest evidence by a student’s question).” (Blitz 2017) 20 “The act of supervising confirmed the cognitive gains that had been made in residency and helped the senior resident feel ready to practice.” (Ince-Cushman 2015) 25 “Supervisors value the fresh ideas and ‘just out of medical school’ knowledge.” (Sabey 2015) 33 Participant quotes “Whatever I have learnt 35 years ago at medical school has changed, so it is a great opportunity for me to learn.” (Ramanayake 2015) 32

|

|

Experience as a clinical teacher can positively impact career trajectory.

|

18, 23, 45, 26, 27, 28,

33, 42, 35, 48, 39

|

Researcher comments “It was perceived to be career enhancing and may impact on [residents’] employability.” (Jones 2020) 45 “Educational scholarship was considered a mode of career advancement rather than practice improvement.” (Law 2016) 28 “Colleagues at their home institution recognized and valued them as educators and scholars, and they were given new opportunities to mentor and lead.” (Turner 2021) 48 “[Clinician teacher training] can be helpful in ways beyond the program’s content, including in obtaining leadership roles, in having the opportunity to establish a relationship with a mentor/advocate, in building a valuable toolkit of resources for teaching and scholarship, and in participating in networking and community building.” (Zipkin 2020) 39

|

|

Clinical teaching can be personally rewarding.

|

18, 20, 21, 23,

25, 45, 26, 27,

30, 33, 34,

40, 48, 38, 44

|

Researcher comments “Informants expressed their task as tutor as interesting and exciting and described commitment and inspiration.” (Von Below 2015) 44 “Internal motivations to teach such as feelings of joy, passion, and a love of learning and teaching. Informants stated that they continue as teachers because of these motivations, despite barriers of inadequate time and compensation” (Larson 2017) 26 “It offers a contrast to the rest of their work and brings satisfaction from sharing expertise, as well as from seeing someone learning and developing in their career.” (Sabey 2015) 33 Participant quotes “Teaching is something that does kind of restore your batteries.” (Jones 2020) 45

|

|

Clinical teaching is a means of networking and forming professional relationships.

|

18, 20, 23, 47,

49, 30, 46, 31,

33, 42, 43, 40, 39

|

Researcher comments “Supervisors emphasized the importance of a supportive practice team and good relationships in helping to manage the workload of supervision.” (Sabey 2015) 33 Participant quotes “I think the networking amongst other educators and finding kind of birds of a feather was really important, because you found other allies in the institution to move forward your educational goals and projects and ideas.” (Zipkin 2020) 39

|

|

Challenges of clinical teaching

|

|

Theme and subthemes

|

|

Illustrative quotes

|

|

Inadequate time for teaching

|

19, 21, 22, 23,

45, 26, 27, 29, 41, 49, 30,

31, 42, 38, 39

|

Researcher comments “Many residents complained that time constraints made teaching difficult and frustrating at times, especially when competing clinical demands left little time for supervision and teaching.” (Morrison 2005) 30 Participant quotes “We just have so many patients and it’s so busy clinically that you really just don’t have the time to sort of sit down for half an hour and chat about this particular topic.” (Hartford 2017) 23 “It takes at least an hour of extra time per day to devote to them the time [the students] need. This usually means leaving later from work or not giving them the time they deserve in being taught.” (Paul 2020) 25 “If you want to do teaching and learning there must be protected time and the facility is responsible to create that time and to protect it.” (de Villiers 2014) 38

|

|

Conflicting responsibilities

|

19, 22, 23, 47, 45, 27,

28, 29, 41,

30, 31, 42, 40,

38, 44, 39

|

Researcher comments “Almost all the participants were involved in the management and administration in their respective workplaces. These roles were performed along with their clinical roles.” (Besigye 2019) 19 “The negatives for [residents] were around increased stress, particularly near exams.” (Jones 2020) 45 “Given their strong sense of identity as clinicians, community faculty participants consistently described conflict between clinical work and scholarship. They described the difficulty of fulfilling all professional roles (ie, clinical, teaching, scholarly) without sacrificing professional time, income, or personal life.” (Law 2016) 28 “Participants described a tug of war between clinical responsibilities and teaching, and the challenges of carving out time for education activities.” (Zipkin 2020) 39 Participant quotes “Taking on too many residents for sure will slow down our practice. And then we suffer financially.” (Hartford 2017) 23 “It’s hard for us to make sure that we’re doing all the documentation we’re supposed to do. . . . You throw a student in the room, and that’s a third thing to distract from your work.” (Scott 2014) 42

|

|

Inadequate communication from medical school regarding learning objectives and expectations

|

20, 24, 29, 41, 31, 43, 39

|

Researcher comments “Many felt disconnected from the clerkship office and academic faculty.” (Paul 2020) 31 “Participants desired clear direction from the clerkship with regard to goals and objectives. . . . However, they also wanted to ensure that these goals and teaching methods were realistic in the community practice setting.” (Paul 2020) 31 Participant quotes “I didn’t feel any support at all from the university. I did get a lot of jobs from the university, but I felt no support.” (Blitz 2018) 20 “Learning objectives at present are written up by students but I feel there should be a general framework from the department.” (Hawken 2011) 24 “Keeping up with constant changes in accreditation requirements.” (Lin 2018) 29

|

|

There are logistical barriers to teaching in the clinical environment.

|

21, 22, 23, 24,

28, 31, 33, 42, 34,

38

|

Researcher comments “Difficulty timetabling, which trainers felt was compounded by pre-existing trainee and practice capacity issues.” (Harrison 2019) 22 “Reduced the number of patient consultations, reduced income, increased costs, such as operating room expenses, and had an impact on consultation and medical procedure wait lists.” (Hartford 2017) 23 “EMR implementation had significantly affected provider efficiency, leaving these preceptors with less time to accommodate the added burden of educating students.” (Paul 2020) 31 “Lack of administrative support and suitable venues were also mentioned as constraints.” (de Villiers 2014) 38

|

Perceptions of Clinical Teaching

Instructing medical students was perceived as a skill to be continuously developed, though some studies reported a lack of confidence in teaching abilities. 29, 41 While some articles investigated residents’ clinical teaching experiences, many described practicing physicians who started teaching only when they became attending physicians. 31, 40 Without prior experience or formal teacher training, many reported acquiring the skills by learning experientially. 36 A need for resources for teacher development was identified, and workshops were considered particularly useful. However, to access such professional development, participants reported, they had to take the initiative to seek opportunities while balancing other clinical responsibilities. 50

Many reported that clinical teaching competency often was presumed by institutions. 20, 23, 27 Primary care clinicians practicing at academic centers, as reported, were expected to take on learners, regardless of their formal background in teaching or precepting trainees. Some studies that focused on residents made a different claim because residents who took on teaching roles were supervised and evaluated on how well they could teach. 25, 34

Studies described the lack of formal institutional recognition and value perceived in teaching compared to other academic pursuits (eg, published research). 19, 20, 29 Some institutions reported having criteria for academic promotion on the basis of teaching or education scholarship, but the specific steps were not as established as they were for research. 9

Clinical Teaching Strategies

A strong focus on learner-centered clinical teaching existed across the articles, with learning objectives being heavily influenced by trainee needs, knowledge gaps, and level of training, making the process relatively personalized to each student.

Clinician teachers’ educational approaches and teaching strategies were diverse. 23, 41, 39 Informal or ad hoc teaching was frequently used to address student-directed learning objectives. Some taught with an observation-and-feedback approach, in which students were given autonomy and subsequently were evaluated on their performance. Didactic teaching was rarely discussed.

Role modeling was one of the most discussed clinical teaching techniques. 26, 27, 43, 36 While described as intentionally modeling a skill or behavior for the learner, clinician teachers were aware that role modeling often occurred passively. It was described as an inherent part of being a clinician teacher due, in part, to the hierarchical structure of medicine. Many clinician teachers reported to have learned through role modeling. The enterprise of clinical teaching appears to be as much about transmitting the culture of medical training as an apprenticeship. As such, certain skills, behaviors, and teaching techniques have trickled down the medical hierarchy.

Building longitudinal mentor-mentee relationships was considered important for effective teaching. Mentorship often was multimodal across domains and included developing clinical skills competencies, career planning, well-being, and creating a collegial environment. 25, 45, 34 Near-peer teaching and mentorship by resident teachers were uniquely valued. Residents were considered more relatable to, and cognitively and socially congruent with students, thereby enhancing the learning experiences of a mentor-mentee relationship. 25, 45, 30, 36

Benefits of Clinical Teaching

A common benefit of clinical teaching is that it is often a shared learning experience. Attending physicians appreciated a wider range of perspectives and updated knowledge as well as an opportunity to reflect on their practices through student feedback. 20, 32 Residents noted that teaching can help them become better learners themselves because teaching reinforces one’s knowledge, skills, and knowledge gaps. 30 Resident teachers are evaluated by their supervisors and thereby gain invaluable feedback on their teaching skills. 25, 34

Clinical teaching experience was perceived to positively impact physicians’ career trajectory. 45 While teaching contributions were not perceived to hold the same prestige in academic institutions compared to publishing, teaching was still viewed as a professional asset because it was a means of networking and forming professional relationships. 28, 48, 39

Clinical teaching was reported to be personally rewarding. 45, 27 The majority of included studies involved participants personally interested in teaching, wherein teaching was protecting them from burnout. 33 Other studies cited altruism as a reason for enjoying teaching; it was a way to give back. 30, 33, 40 Much satisfaction was taken from seeing students improve. Having enthusiastic trainees boosted morale in the clinical environment. 33, 34

Challenges of Clinical Teaching

Inadequate time, often due to competing clinical demands, was a common challenge cited for clinical teaching. Some study participants reported taking more time with patients if they had a student, resulting in decreased clinical productivity and financial losses. 23 Also, ensuring safe practice while teaching was reported as time-consuming. Some attending physician participants noted that near-peer teaching by residents reduced their clinical teaching burdens. From the residents’ perspective, they also faced the challenge of time constraints. 45, 30

Other clinical teaching challenges were the learning objectives and competency expectations of the teaching institution. 20 Those expectations were often broad, and a lack of communication with the students’ academic institutions was a key barrier. 31 Clinician teachers often expressed concern that there was too much content to cover. In practice, learning objectives mainly were directed by the students themselves. 24

Logistical barriers in the clinical environment included lack of space in a practice for students as well as practice patterns that limited teaching (ie, use of electronic medical records during patient interactions). 22, 38 Lack of funding for adequate compensation for clinician teachers’ instructional time was also of concern. 23

This qualitative synthesis explored the experiences and perspectives of primary care clinician teachers regarding teaching and education scholarship in the clinical setting. Four main themes emerged from the literature: perceptions of clinical teaching, clinical teaching strategies, benefits of clinical teaching, and challenges of clinical teaching.

Primary care clinician teachers often lacked formal training in precepting, as well as confidence in their teaching abilities. Studies reported physicians having learned their teaching methods through role modeling by their former preceptors 43, 36 while others described teaching as an experiential skill that they accrued once they became attending physicians. 27, 41 As such, the most common teaching techniques were informal or ad hoc because those approaches were perceived to be intuitive and flexible. 23, 46 While the literature described a desire to become skilled clinician teachers, logistical barriers existed, such as time constraints, lack of compensation, and lack of direction from the academic institutions themselves. Clinician teachers also perceived that academic institutions tended to presume teaching competency while simultaneously holding other scholarly pursuits, such as research, in higher esteem. Excellence in clinical teaching was not viewed as an effective route for achieving academic promotion. 28

Our findings showed that primary care clinician teachers recognized the potential for career satisfaction derived from clinical teaching, in part related to the networking and collaborative aspects of this role. Clinician teachers often reported having a personal interest in teaching and being keen to contribute to students’ learning. Contributing to curriculum development and otherwise engaging in the research or innovation of clinical education rarely were cited as advantages of clinical teaching. The research revealed an overall lack of awareness of education scholarship as a complement to practical teaching experiences.

A disconnect seems to exist between the experiences and perceptions described in the literature and Boyer’s definition of education scholarship, which described teaching practices informed by educational theory, peer-review, and advancement of the field. 6 Addressing this disconnect requires support to build the skills and confidence of clinician teachers. Primary care clinician teachers, particularly those based in community settings, possibly have limited opportunities to advance their diverse skills and teaching experiences. A first institutional step may include increasing awareness of education scholarship as an opportunity to study and improve existing teaching practices, which in turn would benefit both learners and patients. 28 Support may include providing formal education scholarship training, compensation, and protected time to participate in faculty development, as well as institutional recognition for clinician teachers as scholars. Institutions can leverage the existing desire of clinician teachers to improve their skills to develop the capacity to advance teaching practices and educational theory. This synthesis highlighted a need for institutional support in the development of strong education scholars, which could include effective leadership, allocation of resources, and a strong commitment to education scholarship.

Our synthesis had limitations. Education scholarship is currently an underdeveloped area of study in medical education, and few existing articles directly address the issue of education scholarship and Boyer’s framework in primary care. As such, we included geographically diverse studies and recognize that primary care clinical education may vary among sites. Our approach did, however, permit greater applicability of our conclusions across different primary care settings. We included articles that studied clinical teaching in both undergraduate and graduate medical education because the teaching skill set applied to teach clerks and residents is similar but with a graduated difference in the level of responsibility and autonomy. 51 While study inclusion criteria were determined by team consensus, only one author completed the abstract review for final inclusion in the study. We did not supplement our database searches by directly searching relevant journals and reference lists. We did not review articles in chronological order, as is commonly done in meta-ethnographic reviews. 12, 13 A strength of this synthesis was the multidisciplinary research team; each author brought a different perspective in the realm of clinical education, which enhanced the richness of our synthesis and conclusions.

This is the first known synthesis of the qualitative literature on the experiences and perspectives of primary care physicians on clinical teaching. Our research revealed a perceived lack of guidance, resources, and awareness of education scholarship in clinical teaching settings in primary care. Findings from this synthesis could support the development of interventions tailored to address the needs of family medicine clinical teachers. To this end, the implementation of a sustained source of education scholarship support would be an asset to most family medicine departments. Establishing stronger linkages between community-based and academic clinician teachers may be one strategy, as well as bringing opportunities and expertise in education scholarship into the clinical teaching environment. In our own context, we are studying the impact of embedding a part-time medical education scientist (JNY) in the clinical environment of the Women’s College Hospital Academic Family Health team. 52 This education scientist role supports local family medicine clinical teacher engagement in education scholarship by providing individually tailored faculty development mentorship and support in areas such as program development and evaluation, and writing skills. Such contextually tailored institutional responses could be an essential part of ongoing efforts to support the scholarly pursuits of family medicine clinical teachers as they strive to meet the education challenges of their clinical teaching roles and advance their engagement in education scholarship.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Heather Sampson and the John Bradley Summer Research Program for mentorship and support; and Kaitlin Fuller, University of Toronto Education and Liaison Librarian, for the MD Program and Institute of Medical Science, for her assistance in producing the literature search strategy. The Women’s College Hospital Peer Support Writing Group provided valuable insights and support in manuscript preparation.

References

-

-

Sherbino J, Frank JR, Snell L. Defining the key roles and competencies of the clinician-educator of the 21st century: a national mixed-methods study.

Acad Med. 2014;89(5):783-789.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000217

-

Hepworth J, Davis A, Harris A, et al. The four pillars for primary care physician workforce reform: a blueprint for future activity.

Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(1):83-87.

doi:10.1370/afm.1608

-

-

-

Boyer E. Highlights of the Carnegie report: the scholarship of teaching from “scholarship reconsidered: priorities of the professoriate.”

Coll Teach. 1991;39(1):11-13.

doi:10.1080/87567555.1991.10532213

-

Garnett F, Ecclesfield N. Towards a framework for co-creating Open Scholarship.

Res Learn Technol. 2011;19(1):7795.

doi:10.3402/rlt.v19s1/7795

-

Srinivasan M, Li ST, Meyers FJ, et al. “Teaching as a competency”: competencies for medical educators.

Acad Med. 2011;86(10):1,211-1,220.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822c5b9a

-

Van Melle E, Lockyer J, Curran V, Lieff S, St Onge C, Goldszmidt M. Toward a common understanding: supporting and promoting education scholarship for medical school faculty.

Med Educ. 2014;48(12):1,190-1,200.

doi:10.1111/medu.12543

-

-

-

-

Campbell R, Pound P, Morgan M, et al. Evaluating meta-ethnography: systematic analysis and synthesis of qualitative research.

Health Technol Assess. 2011;15(43):1-164.

doi:10.3310/hta15430

-

France EF, Cunningham M, Ring N, et al. Improving reporting of meta-ethnography: the eMERGe reporting guidance.

BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):25.

doi:10.1186/s12874-018-0600-0

-

-

Noyes J, Booth A, Flemming K, et al. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance series-paper 3: methods for assessing methodological limitations, data extraction and synthesis, and confidence in synthesized qualitative findings.

J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;97:49-58.

doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.06.020

-

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews.

BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45-52.

doi:10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

-

Ahluwalia S, Spicer J, Patel A, Cunningham B, Gill D. Understanding the relationship between GP training and improved patient care - a qualitative study of GP educators.

Educ Prim Care. 2020;31(3):145-152.

doi:10.1080/14739879.2020.1729252

-

Besigye IK, Onyango J, Ndoboli F, Hunt V, Haq C, Namatovu J. Roles and challenges of family physicians in Uganda: a qualitative study.

Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2019;11(1):e1-e9.

doi:10.4102/phcfm.v11i1.2009

-

Blitz J, De Villiers M, Van Schalkwyk S. Implications for faculty development for emerging clinical teachers at distributed sites: a qualitative interpretivist study.

Rural Remote Health. 2018;18(2):4482.

doi:10.22605/RRH4482

-

Clark JM, Houston TK, Kolodner K, Branch WT Jr, Levine RB, Kern DE. Teaching the teachers: national survey of faculty development in departments of medicine of U.S. teaching hospitals.

J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(3):205-214.

doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30334.x

-

Harrison M, Alberti H, Thampy H. Barriers to involving GP Speciality Trainees in the teaching of medical students in primary care: the GP trainer perspective.

Educ Prim Care. 2019;30(6):347-354.

doi:10.1080/14739879.2019.1667267

-

Hartford W, Nimmon L, Stenfors T. Frontline learning of medical teaching: “you pick up as you go through work and practice”.

BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):171-171.

doi:10.1186/s12909-017-1011-3

-

Hawken SJ, Henning MA, Pinnock R, Shulruf B, Bagg W. Clinical teachers working in primary care: what would they like changed in the medical school?

J Prim Health Care. 2011;3(4):298-306.

doi:10.1071/HC11298

-

Ince-Cushman D, Rudkin T, Rosenberg E. Supervised near-peer clinical teaching in the ambulatory clinic: an exploratory study of family medicine residents’ perspectives.

Perspect Med Educ. 2015;4(1):8-13.

doi:10.1007/S40037-015-0158-Z

-

-

-

Law M, Wright S, Mylopoulos M. Exploring community faculty members’ engagement in educational scholarship. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(9):e524-e530.

-

Lin S, Nguyen C, Walters E, Gordon P. Residents’ perspectives on careers in academic medicine: obstacles and opportunities.

Fam Med. 2018;50(3):204-211.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.306625

-

Morrison J, Clement T, Nestel D, Brown J. Perceptions of ad hoc supervision encounters in general practice training: A qualitative interview-based study. Aust Fam Physician. 2015;44(12):926-932.

-

Paul CR, Vercio C, Tenney-Soeiro R, et al. The decline in community preceptor teaching activity: exploring the perspectives of pediatricians who no longer teach medical students.

Acad Med. 2020;95(2):301-309.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002947

-

Ramanayake RP, De Silva AH, Perera DP, Sumanasekera RD, Athukorala LA, Fernando KA. Training medical students in general practice: a qualitative study among general practitioner trainers in Sri Lanka.

J Family Med Prim Care. 2015;4(2):168-173.

doi:10.4103/2249-4863.154623

-

Sabey A, Harris M, van Hamel C. ‘It gave me a new lease of life … ’: GPs’ views and experiences of supervising foundation doctors in general practice.

Educ Prim Care. 2016;27(2):106-113.

doi:10.1080/14739879.2015.1113725

-

Silberberg P, Ahern C, van de Mortel TF. ‘Learners as teachers’ in general practice: stakeholders’ views of the benefits and issues.

Educ Prim Care. 2013;24(6):410-417.

doi:10.1080/14739879.2013.11494211

-

Smith CC, McCormick I, Huang GC. The clinician-educator track: training internal medicine residents as clinician-educators.

Acad Med. 2014;89(6):888-891.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000242

-

-

Thampy H, Agius S, Allery L. Clinical teaching: widening the definition.

Clin Teach. 2014;11(3):198-202.

doi:10.1111/tct.12113

-

de Villiers MR, Cilliers FJ, Coetzee F, Herman N, van Heusden M, von Pressentin KB. Equipping family physician trainees as teachers: a qualitative evaluation of a twelve-week module on teaching and learning.

BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):228-228.

doi:10.1186/1472-6920-14-228c

-

Zipkin DA, Ramani S, Stankiewicz CA, et al. Clinician-educator training and its impact on career success: a mixed methods study.

J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(12):3,492-3,500.

doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06049-w

-

Triemstra JD, Iyer MS, Hurtubise L, et al. Influences on and characteristics of the professional identity formation of clinician educators: a qualitative analysis.

Acad Med. 2021;96(4):585-591.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003843

-

Moore P, Ortigoza A, Grant E, Pirazzoli A. Educational expectations of professionals who teach in primary health care in Chile.

Educ Prim Care. 2020;31(2):81-88.

doi:10.1080/14739879.2019.1710863line

-

Scott SM, Schifferdecker KE, Anthony D, et al. Contemporary teaching strategies of exemplary community preceptors—is technology helping? Fam Med. 2014;46(10):776-782.

-

Stenfors-Hayes T, Berg M, Scott I, Bates J. Common concepts in separate domains? family physicians’ ways of understanding teaching patients and trainees, a qualitative study.

BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):108-108.

doi:10.1186/s12909-015-0397-z

-

Von Below B, Haffling AC, Brorsson A, Mattsson B, Wahlqvist M. Student-centred GP ambassadors: perceptions of experienced clinical tutors in general practice undergraduate training.

Scand J Prim Health Care. 2015;33(2):142-149.

doi:10.3109/02813432.2015.1041826

-

Jones M, Kirtchuk L, Rosenthal J. GP registrars teaching medical students—an untapped resource?

Educ Prim Care. 2020;31(4):224-230.

doi:10.1080/14739879.2020.1749531

-

Morrison J, Clement T, Nestel D, Brown J. Perceptions of ad hoc supervision encounters in general practice training: A qualitative interview-based study. Aust Fam Physician. 2015;44(12):926-932.

-

-

Turner TL, Zenni EA, Balmer DF, Lane JL. How full is your tank? A qualitative exploration of faculty volunteerism in a national professional development program.

Acad Pediatr. 2021;21(1):170-177.

doi:10.1016/j.acap.2020.06.140

-

Morzinski J, Simposon D, Marcdante K, Meurer LA, Gilligan MA, Chandler T. Evaluating the career impact of faculty development using matched controls.

Fam Med. 2019;51(10):841-844.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.195240

-

-

-

Chen B, Nyhof-Young J, Fernando O, Heisey R, Freeman R. Building education scholarship capacity in family medicine: a pilot study. Work in Progress poster presented at the 2019 Family Medicine Forum in Vancouver, CAN.

There are no comments for this article.