Until recently, the future for medical school graduates seemed clear. Based on past experience, medical students and educators assumed that graduates would become valued authoritative physicians in a solid, stable health care system.1 That future, however, is no longer certain. With changes in health care and society at-large—including the rise of team care,2 corporate ownership,3 polarization, and increased complexity—professional roles have shifted and public trust in health care has declined. 4, 5 Little is known about what this changing environment means to medical students and their perceptions of their future profession. Therefore, we set out to understand medical students’ views of the future of health care and their place in it.

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

Medical Students’ Views of the Future in a Rapidly Changing World

Robin S. Gotler, MA | Bethany Snyder, MPH | C. Kent Smith, MD | Patricia Moore, MD | James Bindas, MBA | Rebecca S. Etz, PhD | William L. Miller, MD, MA | Kurt C. Stange, MD, PhD

Fam Med. 2024;56(9):541-547.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2024.918294

Background and Objectives: Physicians have long been considered valued members of a solid US health care system. Significant changes in medical education, health care, and society at-large suggest that current medical students may face a different future. To help guide educators and policy makers, we set out to understand medical students’ perceptions of the future of health care and their place in it.

Methods: In year one of a longitudinal study, we conducted in-depth interviews of Case Western Reserve University medical students. A multidisciplinary team performed iterative thematic analyses and sampling until reaching saturation on major themes.

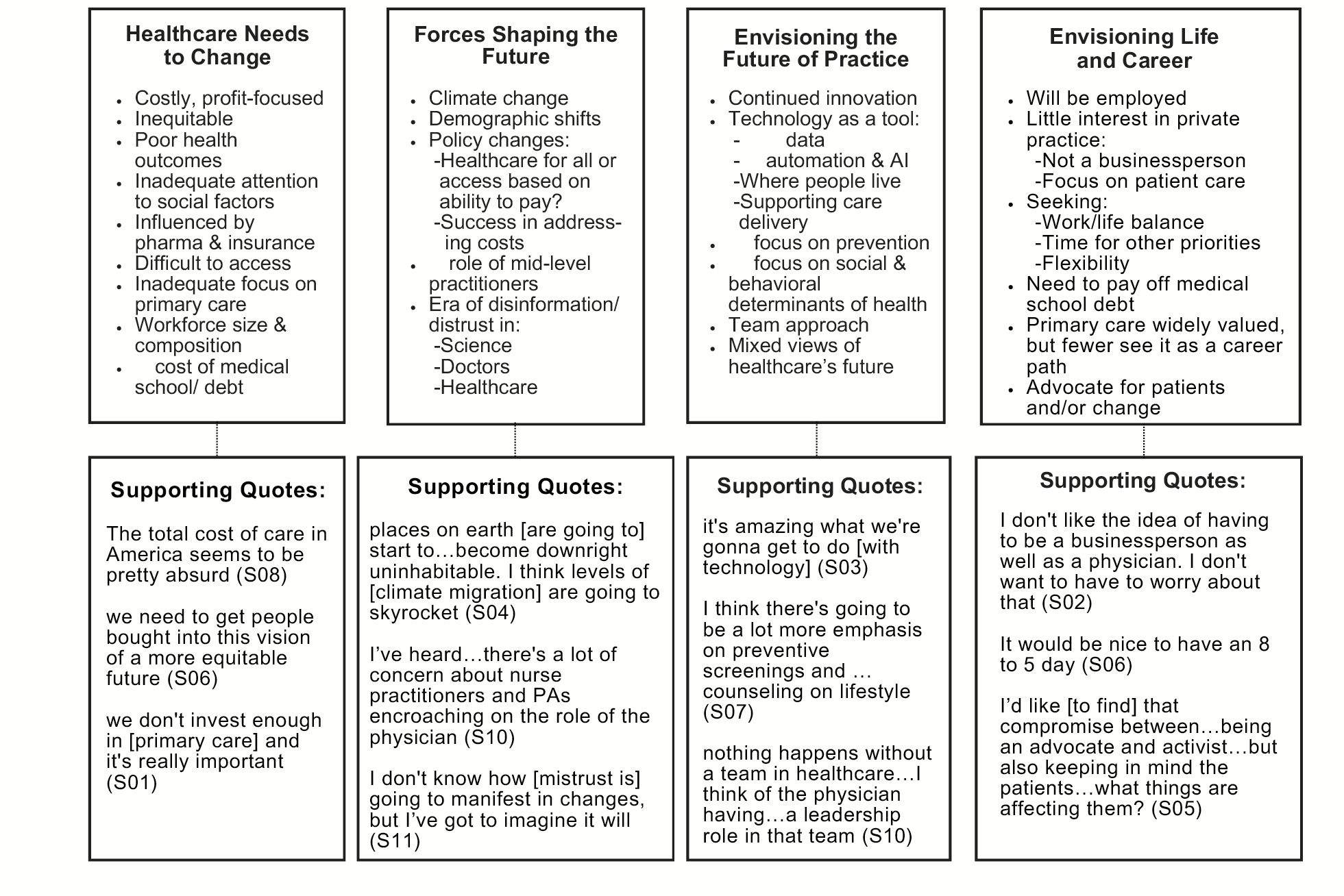

Results: Eleven medical student participants described social and health care issues as major influences on their professional futures. Concerns included health care system failings, unsustainable costs, climate change, demographic shifts, disinformation, and public distrust in health care. Students looked forward to team practice and using technology, data, and artificial intelligence in care delivery. They hoped for greater access and equity in health care, with a focus on prevention and social, behavioral, and environmental drivers of health. Most students expected to be employed rather than in private practice and sought time/flexibility for professional and personal interests. Paying off medical school debt and advocating for patients and change were priorities. Many saw primary care as important, but fewer envisioned it as their career path of choice.

Conclusions: Medical students envision a future shaped by health care systems and social issues. These findings can inform those helping students prepare for uncertainty and rapid change in their careers, their lives, and the lives of their patients.

In Spring 2021, we sent a blast email to Case Western Reserve University medical students inviting them to take part in an interview about their perceptions of health care’s future. Interested students contacted a nonfaculty investigator (R.G.). Word of mouth among students aided recruitment. Our goal was to obtain a robust, information-rich sample.6 Early in recruitment we added a longitudinal component to the study and, therefore, focused on recruiting first- and second-year students. We analyzed interviews, identifying major emergent themes until we reached saturation, 6- 9 that is, the point where substantial new information and new themes no longer emerged. To help diversify the sample, we recontacted two students who suggested additional interviewees with potentially divergent viewpoints; we interviewed the additional students and analyzed those data.

Interviews lasted approximately 60 minutes and were conducted by a staff member (R.G.) experienced in interviewing. Questions were semistructured, and follow-up for clarification and additional detail was solicited during the interview process (see Appendix). Interviews were videorecorded via Zoom and transcribed by the interviewer.

Two coders (B.S., R.G.) reviewed transcripts to develop a preliminary codebook using NVivo 12 (Lumivero) qualitative software. This included independently coding a subset of data, comparing coding to establish code definitions, and using a consensus process to mediate discrepancies. To verify the preliminary codebook, they coded a second round of data. An additional coder (K.S.) joined the analysis to provide adjudication support toward theme development. All coders independently analyzed the coded data to identify emergent themes using an immersion/crystallization process. 10 In this step, the analytic team allowed for emergent codes to develop organically from perspectives raised by participants. Once the data were fully coded, the team met to compare their coding and identify, synthesize, and refine topical themes that explained the apparent significance of the findings. This process continued until saturation was reached and no new emergent themes were apparent. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The team sought alternative interpretations throughout the analysis process, including refining themes through discussion and reexamining original transcripts for confirming/disconfirming text and representative quotations. 7 Study findings were validated using a two-step auditing process. In the first step, content experts in medical education (C.K.S., P.M.) and both medical education and qualitative research (R.S.E., W.L.M.) were given access to the coded data and asked to review the thematic findings based on their experience and practice. In the second step, thematic findings were shared with study participants to verify whether themes identified through analysis matched their perceptions as described.

The study protocol was reviewed and deemed exempt by the Case Western Reserve University Institutional Review Board.

We interviewed 11 medical students, with characteristics outlined in Table 1. Overall, students were acutely aware of the health care environment and its societal context. They were concerned about instability, uncertainties, evolving changes, and what change meant for their future. No one envisioned a cozy practice niche in a stable health care environment.

|

Characteristic |

N=11 |

|

Gender |

|

|

Female |

5 |

|

Male |

6 |

|

Medical s chool year |

|

|

Year 1 |

6 |

|

Year 2 |

4 |

|

Year 3 |

0 |

|

Year 4 |

1 |

|

Home (US region) |

|

|

Northeast |

4 |

|

Southeast |

1 |

|

Midwest |

4 |

|

Southwest |

0 |

|

West |

1 |

|

Multiple |

1 |

|

Rurality |

|

|

Urban |

5 |

|

Rural |

2 |

|

Suburban |

2 |

|

Unknown |

2 |

|

Specialties under consideration (multiple responses permitted) |

N=15 |

|

Surgery |

4 |

|

Primary care (unspecified) |

3 |

|

Family medicine/general internal medicine |

2 |

|

Emergency medicine |

1 |

|

Gastroenterology |

1 |

|

Infectious disease |

1 |

|

OB/GYN (high risk) |

1 |

|

Psychiatry |

1 |

|

Trauma/critical care |

1 |

In the following sections, we summarize our findings within four domains, with additional detail in Figure 1.

Health Care Needs to Change

Medical students had serious concerns about systemic issues in health care and society at-large, and they appealed for change at multiple levels. Concerns included profits, costs, and efficiency; interference and autonomy; and inequity.

Profits, Costs, and Efficiency

Health care’s profit orientation and focus on costs and efficiency were priority issues among interviewees. For some, profits were a moral/ethical issue:

S04

I can’t fathom why anyone would allow a sector like health care to be driven by profit motive. . . . People shouldn’t be . . . crowdfunding their cancer treatments. People shouldn’t be showing up in the emergency room to have a leg amputated because they couldn’t afford their insulin.

For many students, the resulting focus on costs and efficiency has negative effects on patients’ health and clinician satisfaction:

S01

Money is a huge issue in health care and the way reimbursement is done. . . . [Physicians] spend so much time charting and clicking boxes. . . . They don’t get to really spend time with patients.

Interference and Autonomy

Some students envisioned insurance and pharmaceutical company interference as a detriment to their professional autonomy and satisfaction and another area for change:

S02

[A physician] should be able to make a decision based on the patient that’s in front of him, not based on what their insurance company has to say.

S03

It will definitely take away from my fulfillment in life and my satisfaction with my job to have to spend hours fighting for my patients’ care with insurance reps.

Inequity

Health care’s inequities—at both patient care and institutional levels—were on the minds of many students. According to one student,

S03

[Racial disparities are] a huge issue. . . . It just really sickens me how little the health care system seems to care about people.

Another student described urban medical centers

S05

where the people who live right next to the hospital . . . aren’t the ones who are getting this amazing world-renowned care. . . . For me, having come from those people and living in those places, I think that I want to infiltrate that.

Forces Shaping the Future

Many students described urgent environmental, social, and policy issues shaping their futures. While most monitored public opinion and policy, they varied in their views of whether and how problems will be addressed.

Climate Change

Climate change was a top concern for many students:

S07

I hope that there’s going to be a focus on planetary health [in the future] . . . because if that continues to worsen . . . that’s going to contribute to . . . poor health outcomes for the poorest people.

One student described climate change in existential terms:

S09

A lot of us are saying . . . if the climate is supposed to get really bad within the next decade or two, why are we even in medical school? We’re spending our last few good years on earth in the library.

Health Policy

Many students recognized the role that policy, payment, and legislation will play in health care’s future:

S02

I hope . . . we will have policies that improve . . . social factors [like income and educational inequality] because I think that . . . will have a massive effect on people’s health.

Expectations for the future of health care payment varied from major change (single payer plan) to no change (continued payer mix). For several students, retaining the status quo meant a future with a two-tiered system of health care in which some people

S01

have access to more of the resources and . . . the physicians [while others receive] substandard . . . nonphysician care.

For students interested in policy, the need to eliminate special interests was paramount:

S05

Let’s get [insurance companies, pharmaceutical companies] out of the room and let’s get doctors, nurses, PAs, patients . . . to counsel the people who are making policies.

Disinformation and Trust

In a postpandemic era, students expressed concerns about the rise of disinformation and shifting regard for medicine:

S09

In the future . . . when I’m seeing patients . . . I have no idea if the education and the training that I’ve gone through will be respected, if patients will be listening to doctors.

Several students viewed trust with minoritized groups as a particularly important issue for health care’s future:

S02

If [medicine has] lost the trust of Black folks, of Native folks, of Latinx folks, what do we need to do differently and why haven’t we been?

The answer, according to one student, is a more diverse workforce:

S08

When you’re trying to shop for doctors and you see no Black male doctors . . . [y]ou start to assume the worst. . . . The solution is [to] make the job more marketable for Black male doctors.

Envisioning the Future of Practice

Students’ expectations for future practice were mixed, reflecting both problems in health care and hope for positive change.

Innovation

Innovation was widely seen as a strength of the US health care system:

S10

The fact that we put together a [COVID-19] vaccine in less than a year . . . I’m excited to be in a field that has so much potential.

Many students looked forward to using automation, artificial intelligence, and personal data collection technologies in their work:

S06

My future-future vision is for everybody to have access to some sort of concierge primary care artificial intelligence that would help people maintain good health, and then that could interface with actual doctors.

Prevention

Health care will increase its focus on preventing illness/disease to improve health and/or reduce costs, according to several students. One student envisioned

S07

more of a nutrition focus in primary care and teaching patients how to cook and . . . what they should be looking out for . . . in the grocery store.

Team Approach

Regardless of the setting in which they expected to work, students assumed they will be part of a health care team, as described in this comment:

S03

I really love the team approaches. . . . I want to be seeing people as an individual doctor, but also able to gather around with my colleagues and discuss what the best treatment options are.

The Future at-Large

In a health care environment facing internal and external pressures, students expressed mixed views of health care’s future overall. Some saw little hope for change:

S02

I think we’re still going to have a shortage of primary care physicians. I think that health care is going to be more expensive and harder to access.

Others looked for incremental change:

S11

My hope is that market pressure emerges out of . . . movements [like Direct Primary Care] and that forces bigger systems to allow their physicians more autonomy, . . . fewer visits, longer visits.

Still others felt that system-wide change was possible:

S01

I’m optimistic, so I think ultimately we’ll end up with a [health care] system like Canada’s.

Envisioning Life and Career

Even early in medical school, students actively considered their careers and lives within the US health care system.

Most students were unaware of private practice options and expected to be employed by a health care system, freeing them from running a business and allowing them to focus on patient care:

S01

I went into medicine because I don’t want to deal with administration and I don’t want to do business, so part of me likes the idea of being a salaried employee.

For these students, employment meant more time to pursue professional/personal interests:

S04

I do want my profession to be an important part of my life, and I think it’s an important profession, but I don’t want it to devour my life.

Student Debt

While students had mixed feelings about physician salaries, with some suggesting salary cuts to help offset high health care costs, most expressed concerns about their substantial medical school debt:

S10

I’m still working part-time . . . trying to . . . minimize how many loans I do have . . . because it is a minor background stress, like a thundercloud in the background of my mind.

Specialty Choice

Many students valued the critical role of primary care, but fewer envisioned it as a career path. According to one student, debt is a major factor:

S09

The student loan crisis will have to be addressed and medical school tuition will have to be addressed if we want a future for primary care. . . . There’s this immense pressure to specialize, so that way you can have financial independence soon enough to actually enjoy your life, build a retirement. . . . I think primary care [is] headed down a treacherous path unless something is done to address student loans.

Advocacy

Several students expressed a desire to advocate for patients, communities, and a better health care system. For one student, this meant making change from within:

S09

My experience . . . as a rural patient [was] when you travel an hour [to get care] . . . it’s so important to have physicians who understand . . . how important every minute is with their patient. . . . I’m going to have to be a part of the system in order to . . . effect change in a way that brings more equitable care to these people who don’t have access.

Others preferred to advocate at broader levels:

S04

I see myself . . . taking on legislative advocacy . . . participating in the system, but also trying to change it for the better.

In this study, medical students saw a direct line between health care, social, and environmental issues and their careers and lives. They focused not only on developing professional skills, a priority for previous generations, 11 but also on factors that will influence their ability to use those skills. Much prior research on student perceptions has focused on the value-added 12, 13 or hidden curriculum 14, 15 and development of professional identity 16, 17 and personal qualities 18 to meet future health care needs. 13, 19, 20, 21 Consistent with other recent research, we found that students are paying attention to health policy 22 and are committed to advocacy 23 and reform. 24 Medical school debt remains a stressor 25 for students and for workforce diversification efforts.

Issues raised by students, including deep concern about climate change 26 and social issues, enthusiasm for technology, 27 and desire to balance work, family, and other priorities reflect characteristics often attributed to the Gen Z and millennial generations. 28- 30 There is, however, tension within some of their stated goals and values, for example, the decision to be employed versus a desire for autonomy, an interest in advocacy but a desire for life balance, and excitement around technological change but skepticism about the ability to effect social/health care change. The frustration and helplessness expressed by some students is shared by their larger generational cohort. Given the high rate of mental health issues among millennials and Gen Zers, 31 these tensions may be noteworthy for medical educators and policy makers.

Our findings suggest the importance of curricular changes that address the multiple levels of students’ concerns. To address their broadest concerns, we recommend that curricula include a social and environmental context for health care delivery and a focus on health equity and community/population health. Opportunities to utilize emerging technologies and work in interdisciplinary teams will help prepare students for an evolving practice landscape. 13, 16, 19, 20 In an era of moral distress, educators also may consider addressing practical challenges facing employed physicians, for example, the challenges of advocating on behalf of patients while meeting organizational expectations. Addressing such issues as building communities of practice and speaking truth to power may be relevant. Given students’ concerns about rapid changes and instabilities in health care, society, and the world, continued attention to their stress levels and mental health, as well as efforts to normalize or at least acknowledge these stresses, are imperative. 12, 19, 20

This study is limited to a single private medical school, and students’ focus on the larger environment may have been enhanced by the COVID-19 pandemic. 32 We did not collect data on age and race and were therefore unable to consider the effects of those characteristics on students’ views. Our goal was to better understand students’ perceptions of the future, regardless of the accuracy of those perceptions.

This work offers a preliminary step in exploring how students’ path to medical practice can be reexamined and reimagined in a rapidly changing world. Our findings suggest the promise of future research integrating quantitative and qualitative data in broader samples across multiple institutions and examining how students’ views change over time during training and clinical practice. Our findings may provide timely topics of interest and specific questions for broadly distributed medical student survey studies.

Medical students are paying attention to the environment in which they will practice and the uncertainty shaping it. Understanding and supporting their interests in personal, system, societal, and environmental contexts is likely to foster the development of the kinds of flexible, connected, and aware physicians that the future calls for.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the University Suburban Health Center Foundation for its support and to the students who gave their time and insights to this study.

References

-

Starr P. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. Basic Books; 1982.

-

Smith CD, Balatbat C, Corbridge S, et al. Implementing optimal team-based care to reduce clinician burnout. NAM Perspectives. National Academy of Medicine; 2018. doi:10.31478/201809c

-

Furukawa MF, Kimmey L, Jones DJ, Machta RM, Guo J, Rich EC. Consolidation of providers into health systems increased substantially, 2016-18. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(8):1,321-1,325. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00017

-

Stolzenberg L, Huang A, Usman M, MacGregor G. A descriptive survey investigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the public’s perception of healthcare professionals. Cureus. 2023;15(7):e41703. doi:10.7759/cureus.41703

-

World Economic Forum. People have lost trust in healthcare systems because of COVID. How can the damage be healed? March 25, 2022. Accessed November 2, 2023. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/03/trust-health-economy-pandemic-covid19

-

Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Clinical research: a qualitative trail map within a mixed-methods world. In: Crabtree BF, Miller, WL, auths. Doing Qualitative Research. 3rd ed. SAGE; 2023:3-36.

-

Crabtree BF, Miller WL. The dance of interpretation and frustrations of Sisyphus. In: Crabtree BF, Miller, WL, auths. Doing Qualitative Research. 3rd ed. SAGE; 2023:183-200.

-

Sandelowski M. Sample size in qualitative research. Res Nurs Health. 1995;18(2):179-183. doi:10.1002/nur.4770180211

-

Miller WL, Crabtree BF. Qualitative analysis: how to begin making sense. Fam Pract Res J. 1994;14(3):289-297.

-

Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Immersion/crystallization organizing style of analysis. In: Crabtree BF, Miller, WL, auths. Doing Qualitative Research. 3rd ed. SAGE; 2023:237-252.

-

Haas J, Shaffir W. The professionalization of medical students: developing competence and a cloak of competence. Symbolic Interact. 1977;1(1):71-88. doi:10.1525/si.1977.1.1.71

-

Leep Hunderfund AN, Starr SR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Value-added activities in medical education: a multisite survey of first- and second-year medical students’ perceptions and factors influencing their potential engagement. Acad Med. 2018;93(10):1,560-1,568. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002299

-

Pershing S, Fuchs VR. Restructuring medical education to meet current and future health care needs. Acad Med. 2013;88(12):1,798-1,801. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000020

-

Karnieli-Miller O, Vu TR, Frankel RM, et al. Which experiences in the hidden curriculum teach students about professionalism? Acad Med. 2011;86(3):369-377. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182087d15

-

Karnieli-Miller O, Vu TR, Holtman MC, Clyman SG, Inui TS. Medical students’ professionalism narratives: a window on the informal and hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 2010;85(1):124-133. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c42896

-

Ross PT, Williams BC, Doran KM, Lypson ML. First-year medical students’ perceptions of physicians’ responsibilities toward the underserved: an analysis of reflective essays. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(9):761-765. doi:10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30672-6

-

Kay D, Berry A, Coles NA. What experiences in medical school trigger professional identity development? Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(1):17-25. doi:10.1080/10401334.2018.1444487

-

Hurwitz S, Kelly B, Powis D, Smyth R, Lewin T. The desirable qualities of future doctors—a study of medical student perceptions. Med Teach. 2013;35(7):e1332-e1339. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2013.770130

-

Maeshiro R, Johnson I, Koo D, et al. Medical education for a healthier population: reflections on the Flexner report from a public health perspective. Acad Med. 2010;85(2):211-219. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c885d8

-

Berwick DM, Finkelstein JA. Preparing medical students for the continual improvement of health and health care: Abraham Flexner and the new “public interest.” Acad Med. 2010;85(9,suppl):S56-S65. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ead779

-

Crandall SJ, Reboussin BA, Michielutte R, Anthony JE, Naughton MJ. Medical students’ attitudes toward underserved patients: a longitudinal comparison of problem-based and traditional medical curricula. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2007;12(1):71-86. doi:10.1007/s10459-005-2297-1

-

Dugger RA, El-Sayed AM, Messina C, Bronson R, Galea S. The health policy attitudes of American medical students: a pilot survey. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140656. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0140656

-

Chimonas S, Mamoor M, Kaltenboeck A, Korenstein D. The future of physician advocacy: a survey of U.S. medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):399. doi:10.1186/s12909-021-02830-5

-

Rook JM, Winkelman TNA, Fox JA, et al. Looking to the future: medical students’ views on health care reform and professional responsibility. Acad Med. 2019;94(9):1,361-1,368. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002621

-

Phillips JP, Wilbanks DM, Salinas DF, Doberneck DM. Educational debt in the context of career planning: a qualitative exploration of medical student perceptions. Teach Learn Med. 2016;28(3):243-251. doi:10.1080/10401334.2016.1178116

-

Tyson A, Kennedy B, Funk C. Gen Z, Millennials Stand Out for Climate Change Activism, Social Media Engagement With Issue. Pew Research Center; 2021. Accessed May 29, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2021/05/26/gen-z-millennials-stand-out-for-climate-change-activism-social-media-engagement-with-issue

-

Hopkins L, Hampton BS, Abbott JF, et al. To the point: medical education, technology, and the millennial learner. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(2):188-192. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2017.06.001

-

Twenge JM. Generations: The Real Differences Between Gen Z, Millennials, Gen X, and Silents—and What They Mean for America’s Future. Atria Books; 2023.

-

Deloitte. The Deloitte global 2022 Gen Z and millennial survey. 2022. Accessed May 29, 2023. https://www.deloitte.com/global/en/issues/work/genzmillennialsurvey-2022.html

-

Francis A. Gen Z: The workers who want it all. BBC. June 14, 2022. Accessed May 29, 2023. https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20220613-gen-z-the-workers-who-want-it-all

-

Lucero JE, Emerson AD, Bowser T, Koch B. Mental health risk among members of the millennial population cohort: a concern for public health. Am J Health Promot. 2021;35(2):266-270. doi:10.1177/0890117120945089

-

Tempski P, Arantes-Costa FM, Kobayasi R, et al. Medical students’ perceptions and motivations during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0248627. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0248627

Lead Author

Robin S. Gotler, MA

Affiliations: Center for Community Health Integration, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH | The Larry A. Green Center, Richmond, VA

Co-Authors

Bethany Snyder, MPH - Center for Community Health Integration, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH

C. Kent Smith, MD - Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH

Patricia Moore, MD - Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH

James Bindas, MBA - Center for Community Health Integration, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH | The Larry A. Green Center, Richmond, VA

Rebecca S. Etz, PhD - The Larry A. Green Center, Richmond, VA | Department of Family Medicine and Population Health, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA

William L. Miller, MD, MA - The Larry A. Green Center, Richmond, VA | Department of Family Medicine, Lehigh Valley Health Network, Allentown, PA | Department of Family Medicine, Morsani College of Medicine, University of South Florida, Allentown, PA

Kurt C. Stange, MD, PhD - Center for Community Health Integration, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH | The Larry A. Green Center, Richmond, VA | Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH | Departments of Population and Quantitative Health Sciences, Oncology, and Sociology, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH

Corresponding Author

Robin S. Gotler, MA

Correspondence: Center for Community Health Integration, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH

Email: rsh@case.edu

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.