Background and Objectives: With a projected primary care physician shortage, efforts must be made to increase the number of students choosing family medicine. Studies have explored what might influence student choice of family medicine, though questions remain about the impact of medical school policies and processes, including for admissions, as well as longitudinal tracks. This study explores some of these structural and institutional factors and how they are associated with rates of students entering into family medicine in subsequent years.

Methods: Responses from a 2016 survey of family medicine department chairs were matched to 2017–2019 institutional family medicine graduate rates to compare the rates of students entering family medicine with (a) inclusion of primary care or family medicine in the medical school’s mission statement; (b) perceived support of the dean’s office in increasing family medicine teaching and leadership presence in the medical school curriculum; (c) whether the admissions committee had a charge to seek out applicants interested in primary care; and (d) the presence of Liaison Committee on Medical Education designated tracks in primary care/family medicine.

Results and Conclusions: Overall, schools whose admissions committees had a specific charge to seek out applicants interested in primary care were consistently more likely than their peer institutions to match more students into family medicine. Other institutional factors may play a role, particularly school mission statements and rural longitudinal tracks. The results of this study have helped to identify where departments of family medicine might focus institutional advocacy to support learners in choosing and subsequently matching into family medicine.

Predictions suggest that the United States could experience a shortage of between 21,400 and 55,200 primary care physicians by 2033. 1 To meet the forecasted demand, efforts must be made to increase the number of students choosing primary care specialties like family medicine.

Studies have explored what might impact student choice of family medicine, including institutional factors, 2-4 and this evidence was summarized in a recent scoping review. 5 One major gap noted in the review was a lack of discussion around the development and impact of medical school policies, including admissions policies and procedures on student interest, as well as how student longitudinal exposure to primary care faculty throughout the medical school curriculum may influence student choice. This study adds to the literature on how structural and institutional factors are associated with match rates into family medicine in subsequent years. 5

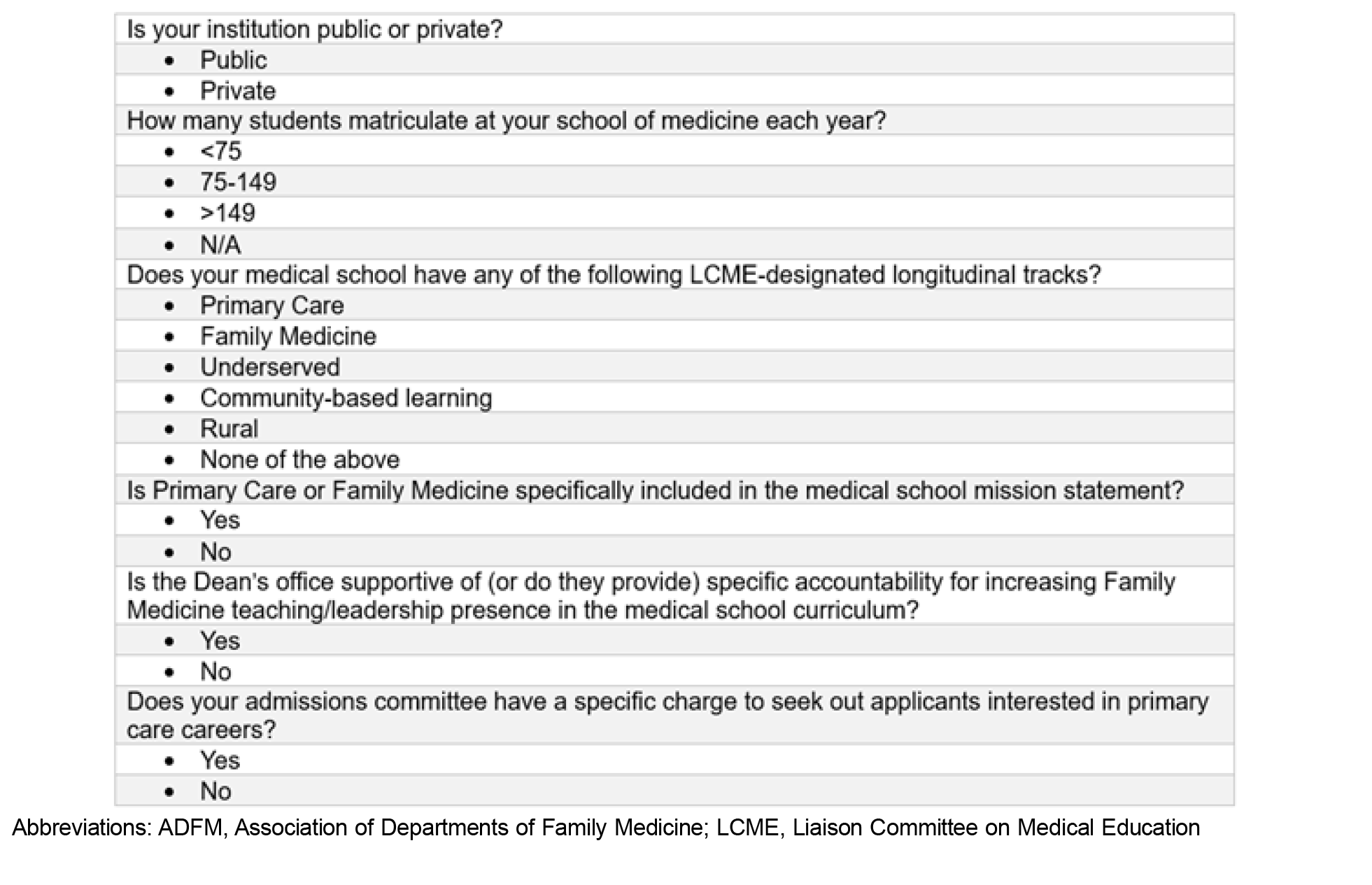

This study matched data from the 2016 Association of Departments of Family Medicine (ADFM) department chair annual survey with data from the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) residency census (referred to throughout as graduate data) to compare rates of students entering into family medicine residency programs from each medical school in 2017, 2018, and 2019. The ADFM membership includes nearly all family medicine department chairs from allopathic medical schools as well as some from osteopathic schools and large regional medical centers; these members are surveyed on an annual basis about key questions of interest for the organization. The 2016 survey asked about programmatic offerings with evidence for or hypotheses of correlation to higher rates of graduates entering family medicine, specifically, (a) the inclusion of primary care or family medicine in the medical school’s mission statement; (b) the chair’s perceived support of the dean’s office in providing accountability for increasing family medicine teaching and leadership presence in the medical school curriculum; (c) whether the admissions committee had a charge to seek out applicants interested in primary care; and (d) the presence of Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) designated tracks in primary care/family medicine (Figure 1).

We chose these data to have multiple years of pre-COVID-19 graduate data to connect to the survey data for longitudinal consideration. Data from the surveys and the graduate rates were combined using the following attribution logic: For institutions with a single location, a one-to-one match was applied; and for institutions with multiple campuses reporting a single institutional graduate rate, a one-to-many match was used. When multiple surveys were submitted by more than one individual at a particular institution (ie, branch campuses), preference was given to the main campus response. Surveys from large regional medical centers and those without complete data were excluded from the analysis. The Georgetown University Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this study as exempt, and a data use agreement was completed with AAFP for the census data.

The final matched dataset encompassed 92 medical schools. We compared the primary outcome variable, family medicine graduate rate, to the main variables of interest from the 2016 survey using a series of mixed-effects models. Each model assessed the effect of individual survey questions on the graduate rate, treating the response to each question as a predictor and accounting for school-level variability and temporal correlation across years. We treated the responses to each survey question (Yes, N/A, and No) as categorical fixed effects, and “No” was set as the reference category for all. We included a random intercept in each model to account for variations among schools. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

The 2016 ADFM survey had 112 responses from 152 members at the time, a 73.6% response rate. With 92 responses in the matched dataset, the study sample represents nearly two-thirds of all departments of family medicine. Institutional characteristics and offerings for this matched sample are shown in Table 1.

|

Response

|

N=92

n

(%)

|

|

Number of students matriculating (institution size)

|

|

|

<75

|

5 (5.4)

|

|

75–149

|

35 (38.0)

|

|

>149

|

52 (56.5)

|

|

School type

|

|

|

Public

|

67 (72.8)

|

|

Private

|

25 (27.2)

|

|

Primary care or family medicine is specifically included in the medical school mission statement.

|

21 (22.8)

|

|

Dean’s office is perceived to be supportive of/provide specific accountability for increasing family medicine teaching/leadership presence in the medical school curriculum.

|

64 (69.6)

|

|

Admissions committee has a specific charge to seek out applicants interested in primary care careers.

|

28 (30.4)

|

|

Does your medical school have any of the following LCME-designated longitudinal tracks?

|

|

|

Primary care

|

9 (9.8)

|

|

Family medicine

|

10 (10.9)

|

|

Underserved

|

8 (8.7)

|

|

Community-based learning

|

7 (7.6)

|

|

Rural

|

17 (18.5)

|

|

None of the above

|

59 (64.1)

|

Schools whose admissions committees had a specific charge to recruit students for primary care careers were significantly more likely to graduate students into family medicine (P=.04). We found no statistical differences in the percentage of students going into family medicine by the department chair’s perception of whether or not the dean’s office was supportive of primary care, whether or not primary care was included in the medical school mission statement, or across schools with LCME-designated longitudinal tracks (Table 2).

|

|

Parameter estimate for affirmative (Yes) response

|

Standard error for parameter

estimate

|

P

value model

N=92

|

|

Dean’s office is perceived to be supportive of/provide specific accountability for increasing family medicine teaching/leadership presence in the medical school curriculum.

|

0.008

|

0.115

|

.314

|

|

Primary care or family medicine is specifically included in the medical school mission statement.

|

0.023

|

0.012

|

.070

|

|

Admissions committee has a specific charge to seek out applicants interested in primary care.

|

0.039

|

0.011

|

.0004

|

|

Have a primary care longitudinal track

|

0.032

|

0.017

|

.163

|

|

Have a family medicine longitudinal track

|

-0.006

|

0.017

|

.791

|

|

Have an underserved track

|

-0.008

|

0.019

|

.773

|

|

Have a community-based learning track

|

-0.010

|

0.0198

|

.741

|

|

Have a rural track

|

-0.030

|

0.013

|

.063

|

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This study had the unique ability to pair family medicine graduate rates with responses from each school’s family medicine department chair about institutional structures that may increase the number of students choosing family medicine. Overall, we found that schools whose admissions committees had a specific charge to seek out applicants interested in primary care were more likely than their peer institutions to graduate more students into family medicine. Those with a primary care-specific mission statement and which offer rural tracks also may be more likely to graduate more students into family medicine, though our aggregated analysis was inconclusive. These data supplement a recent synthesis about admissions practices that support primary care 3 by highlighting the role of a committee’s intent, and they complement previous literature on the role of primary care-oriented tracks in medical school 6, 7 by looking nationally and adding in outcomes data.

Our results suggest that an opportunity exists for departments to increase their engagement with the admissions committee and advocate for the creation of a specific charge to seek out applicants interested in primary care careers. More than half of the respondents (64.9%) indicated that their school did not have any type of longitudinal track for students. Increasing the number of LCME-dedicated longitudinal tracks, particularly those focused on rural health, might be worth investigating further; additional studies are needed to assess which elements of a longitudinal track may influence family medicine specialty choice.

A major limitation of this study was that while we know that student choice of specialty is impacted by many variables, we did not have individual or additional institutional data to create more robust modeling to account for these other factors. Additionally, we opted to explore a pre-COVID-19 sample but know that much has changed in medical education in the last few years. Finally, many osteopathic medical schools are producing an increasing proportion of family medicine residents, 8 but few of these schools have a clinical department structure that includes the different specialties; so, without a department of family medicine, they are not members of ADFM and thus are acutely underrepresented in this study. Learning more about the institutional influences of osteopathic medical schools is a major opportunity for the discipline.

Overall, the results of this study have helped to identify where departments of family medicine might want to focus their advocacy at an institutional level to influence the outcomes of their learners in choosing family medicine. More work will need to be done to explore how these factors play out at an institutional level and what has worked for departments that have successfully advocated for changes; an opportunity may exist for peer sharing among departments, for example, within ADFM mechanisms such as their annual conference. Increasing student interest in family medicine requires a multipronged approach at the institutional, departmental, community, and individual level; this study adds to the growing body of evidence on what may help us move the discipline forward.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the American Academy of Family Physicians for partnering on the graduate data by institution and to Dr Valeriy Korostyshevskiy for his early biostatistical support of this project.

References

-

Association of American Medical Colleges. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2019 to 2034. AAMC; June 2021.

-

Seehusen DA, Raleigh MF, Phillips JP, et al. Institutional characteristics influencing medical student selection of primary care careers: a narrative review and synthesis.

Fam Med. 2022;54(7):522-530.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2022.837424

-

Raleigh MF, Seehusen DA, Phillips JP, et al. Influences of medical school admissions practices on primary care career choice.

Fam Med. 2022;54(7):536-541.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2022.260434

-

Wimsatt LA, Cooke JM, Biggs WS, Heidelbaugh JJ. Institution-specific factors associated with family medicine residency match rates.

Teach Learn Med. 2016;28(3):269-278.

doi:10.1080/10401334.2016.1159565

-

Phillips JP, Wendling AL, Prunuske J, et al. Medical school characteristics, policies, and practices that support primary care specialty choice: a scoping review of 5 decades of research.

Fam Med. 2022;54(7):542-554.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2022.440132

-

-

Ledford CJW, Guard EL, Phillips JP, Morley CP, Prunuske J, Wendling AL. How medical education pathways influence primary care specialty choice.

Fam Med. 2022;54(7):512-521.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2022.668498

-

Pristell C, Byun H, Huffstetler A. Osteopathic medical schools produce an increasing proportion of family medicine residents. Am Fam Physician. 2024;109(2):114-115.

There are no comments for this article.