Background and Objectives: Leadership roles may increase symptoms of loneliness that negatively impact health outcomes and job performance. This study examined loneliness among family medicine department chairs and explored mitigating factors.

Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional survey of family medicine chairs in the United States and Canada within the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey. The survey assessed loneliness symptoms in respondents’ professional lives, professional relationships, organizational engagement, and demographics. Loneliness scores ranged from 3 (least lonely) to 9 (most lonely), with scores of 6 or greater indicating loneliness.

Results: Of 227 eligible chairs, 114 (50.2%) responded. The mean loneliness score was 4.77, with 35.8% of respondents classified as lonely. While 56.1% reported no change in loneliness since becoming chair, 29.4% reported increased feelings of loneliness. The number of trusted colleagues within the chair’s institution was significantly correlated with decrease in loneliness symptoms. Chairs reporting no trusted institutional colleagues had a mean loneliness score of 7 compared to lower scores among those with one or more trusted colleagues. External professional relationships and organizational engagement were not significantly associated with loneliness. No significant differences in loneliness were found based on age, gender, or underrepresented in medicine status.

Conclusions: More than one-third of family medicine chairs experience loneliness in their professional lives. Having trusted colleagues within one’s institution is associated with less identified loneliness and may be a mitigating factor. This study demonstrates the importance of identifying and mitigating loneliness in family medicine chairs and other leaders in academic medicine.

Loneliness rates among Americans range from 44%–67%, with younger generations experiencing more loneliness.1 The impact of loneliness on health and well-being has been extensively documented in the literature, with negative effects noted for physical functioning2,3 and mental health.4 People who are lonely have higher overall mortality2 and higher rates of depression, sleep difficulty, and suicidality.4 Employees who are lonely are less engaged with their jobs, have lower commitment to the organization,5 exhibit higher stress-related absenteeism, and indicate higher intention to leave their job within 12 months.6

In general, those who assume a leadership position experience an increase in negative emotions, including loneliness.7 Research shows that rising to a higher position within an organization results in fewer perceived workplace friendships.8 Substantial loneliness is reported among family medicine clinicians, with a recent survey showing that 28% of family physicians scored high on a loneliness scale. This number was higher among women and underrepresented minorities.9

Loneliness in health care executives also has been described.9 Given the impending leadership crisis in family medicine, and the difficulty in filling vacant chair roles,10 promoting longevity and satisfaction in the role of chair is important. Loneliness and burnout have been cited as reasons for shorter terms in the chair position among anesthesiology chairs.10

The experience of loneliness is a common yet underrecognized challenge for many department chairs. Roundtable discussions were held on the “Loneliness of the Chair” at the Association of Departments of Family Medicine (ADFM) national conferences in 2020 and 2022. During these sessions, we explored shared challenges as chairs and strategies to overcome them, including how to find mentors, develop allies, and engage in regional or national collaboration. These sessions generated questions and prompted us to conduct a nationwide survey on loneliness among family medicine chairs.

The purpose of this study was to measure loneliness among family medicine department chairs and explore possible mitigating factors, such as internal and external relationships and participation in national organizations.

Recruitment

This binational survey invited all family medicine department chairs from both the United States and Canada. All family medicine department chairs, as identified by ADFM, were eligible to participate in this study. Email invitations to participate were delivered with the survey utilizing the online program SurveyMonkey (SurveyMonkey Inc). After the initial email invitation, five follow-up emails to encourage nonrespondents to participate were sent weekly, and a sixth reminder was sent the morning the survey closed.

Survey Design

We submitted 10 loneliness-related questions for the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) annual department chair survey (Appendix A). We used CERA’s survey framework and distribution methods to facilitate data collection. The methodology of a CERA survey has been described previously in detail.11

We assessed loneliness using three items from the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: relational connectedness, social connectedness, and self-perceived isolation.12 Respondents answered questions about their professional lives as department chairs and not their personal lives. Questions were rated on a 3-point scale: 1 = hardly ever; 2 = some of the time; and 3 = often. Items were summed to produce a total score ranging from 3 (least lonely) to 9 (most lonely). Some researchers have defined scores of 3 to 5 as “not lonely” and 6 to 9 as “lonely.”6-9 Additional questions were elucidated during our roundtable discussion about loneliness with chairs. The survey also assessed demographic characteristics, which were included in our analysis. This project was approved by the American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board in August 2023. Data were collected from August 8 to September 15, 2023.

Analysis Plan

We produced descriptive statistics (frequencies, means, and standard deviations) to summarize the study variables. We used independent samples t tests to determine associations between demographic variables and loneliness. We used analysis of variance to determine whether loneliness is mitigated by having trusted colleagues and/or engaging with national networks. Analysis of variance also determined relationships between the amount of loneliness experienced and intention to leave the role. We dichotomized loneliness and ran several logistic regression analyses. These analyses failed to provide additional insight into the experience of loneliness, nor did they shed new light on mitigating factors.

Participants

At the time of the survey, 213 US department chairs and 17 Canadian department chairs were identified. One US email was undeliverable. One person in the United States and one person in Canada indicated they were no longer a department chair, and no replacement chair was identified. The survey was delivered to 227 department chairs (211 US and 16 Canadian). A total of 114 department chairs responded to the survey invitation. The overall response rate for the survey was 50.22%.

Demographics

Participant demographics are shown in Table 1. Most participants were in their 50s (36.8%) or 60s (34.2%). The majority (71%) were White, located in New England (55.3%), and had spent less than 5 years in the role of department chair (49.1%).

|

Characteristic

|

n (%)

|

|

Age

|

|

30–39 years

|

4 (3.6)

|

|

40–49 years

|

17 (14.9)

|

|

50–59 years

|

42 (36.8)

|

|

60–69 years

|

39 (34.2)

|

|

70+ years

|

9 (7.9)

|

|

Missing

|

3 (2.6)

|

|

Gender

|

|

Male/man

|

70 (61.4)

|

|

Female/woman

|

38 (33.3)

|

|

Missing

|

6 (5.3)

|

|

Race/ethnicity

|

|

White

|

81 (71)

|

|

Asian

|

10 (8.8)

|

|

Hispanic/Latino

|

6 (5.3)

|

|

Black or African American

|

3 (2.6)

|

|

Other/chose not to disclose

|

3 (2.6)

|

|

Missing

|

11 (9.7)

|

|

Underrepresented in medicine statusa

|

23 (20.2)

|

|

Location of department

|

|

New England

|

63 (55.3)

|

|

Middle Atlantic

|

22 (19.3)

|

|

South Atlantic

|

11 (9.7)

|

|

West South Central

|

7 (6.1)

|

|

East South Central

|

2 (1.7)

|

|

Other

|

9 (7.9)

|

|

Total years served as department chair

|

|

Less than 5 years

|

56 (49.1)

|

|

5–15 years

|

36 (31.6)

|

|

15–25 years

|

13 (11.4)

|

|

25+ years

|

9 (7.9)

|

|

Participants considered lonely (score 6–9)

|

39 (34.2)

|

Survey Results

The overall mean loneliness score was 4.75 (SD: 1.70). Of the respondents, 34.2% were considered “lonely,” with loneliness scores greater than or equal to 6 out of 9. We noted a bimodal effect of the loneliness scale with rates of loneliness increasing from 11.9%–23.9% between a score of 5 (not lonely) and a score of 6 (lonely). Distributions of responses to each question on the UCLA Loneliness Scale are shown in Figure 1.

Most (56.1%) respondents experienced no change in feelings of loneliness since becoming a chair. Of the 43.9% who did report a change, 29.4% reported that their feelings of loneliness increased, compared to 11.9% who reported a decrease and 58.7% who reported that their feelings stayed the same. Loneliness was not found to be associated with intention to leave the role of chair.

We found no significant differences in loneliness scores by age, gender, or among respondents who self-identified as underrepresented in medicine versus those who did not.

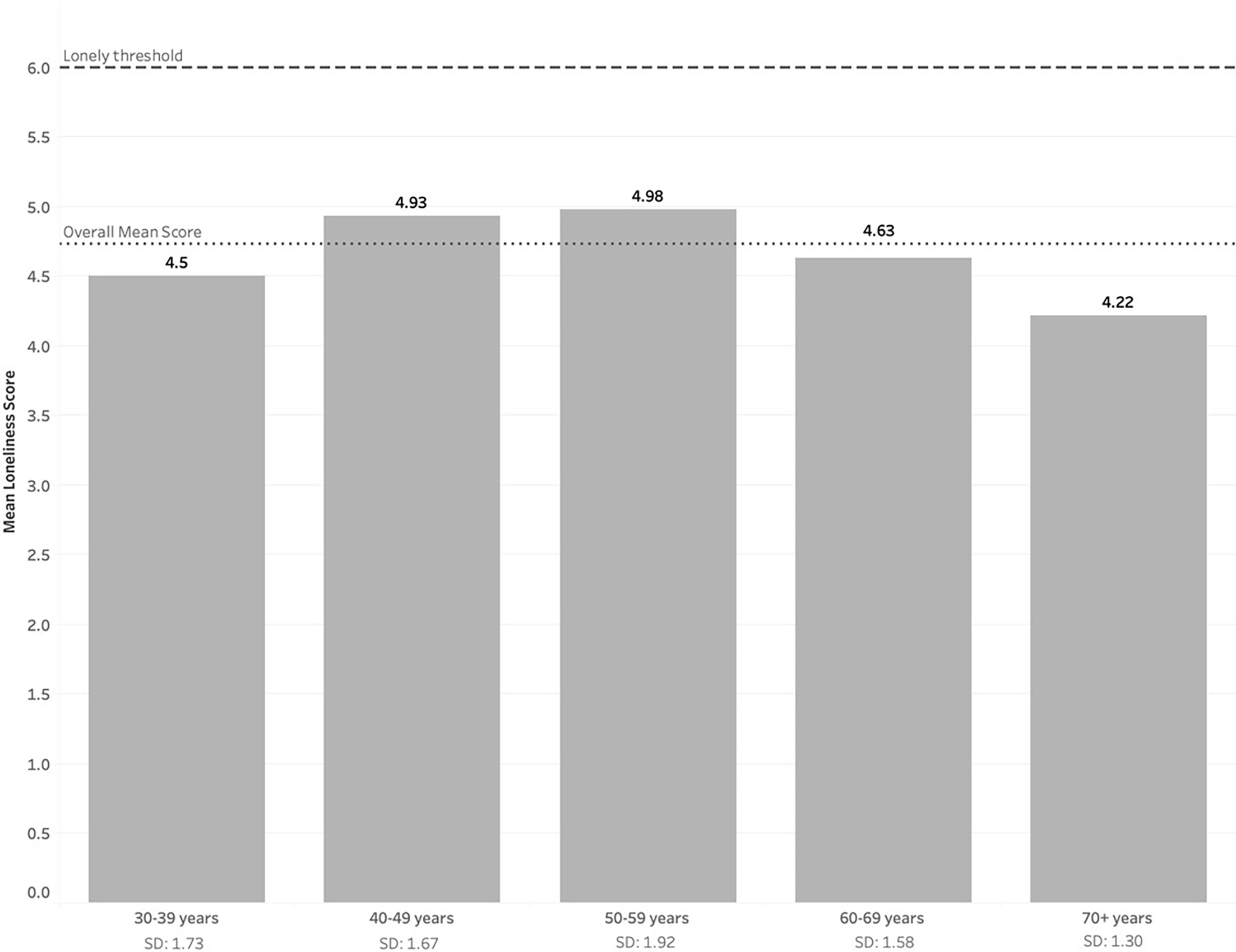

However, the distribution of loneliness scores by age bracket were positively skewed (Figure 2.

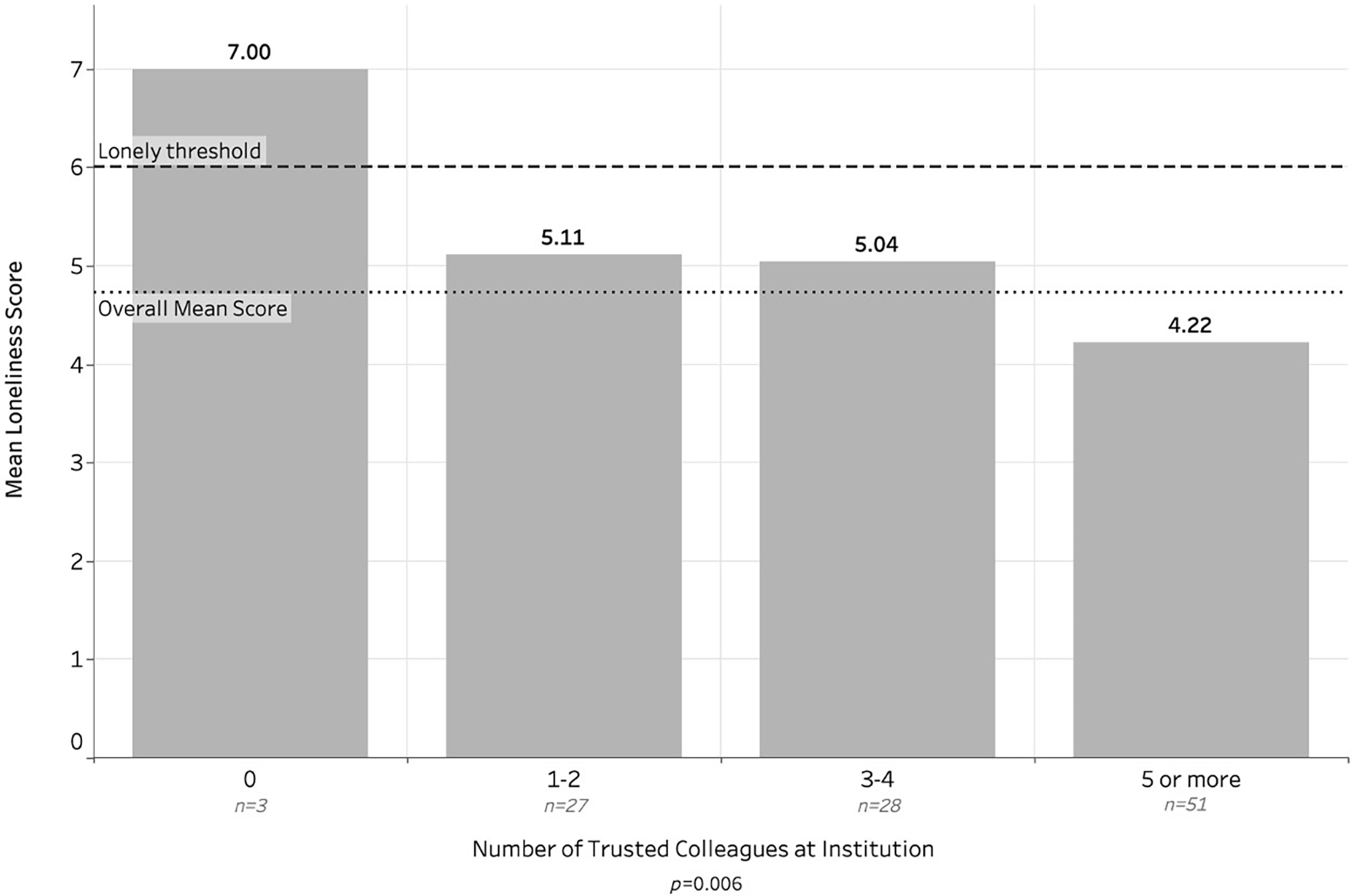

Mean loneliness scores were significantly negatively correlated with the number of trusted colleagues that respondents reported as part of their institution (Figure 3). No such correlation was found for trusted colleagues outside of the respondent’s institution, participation in professional organizations or meetings, or active engagement in ADFM.

This study found that more than half of family medicine department chairs are experiencing at least one symptom of loneliness, and more than one-third are lonely in their professional lives. The study also found that having trusted colleagues at their home institutions helped to mitigate symptoms of loneliness. In contrast, having trusted colleagues outside the institution or attending national conferences did not mitigate loneliness. Enhancing opportunities for chairs to network locally and strengthen relationships with colleagues at their institution may be a helpful strategy to combat loneliness and its negative consequences. Given the well-studied connection between social isolation and poor health outcomes,13 these opportunities may be especially important for chairs who have no contacts.

We found no differences in loneliness based on gender or self-reported underrepresented in medicine status (Table 2). This finding is in contrast to a similar study9 that showed higher rates of loneliness among women and underrepresented minorities. However, that study did not include physicians in positions of leadership. A future study might explore whether women and underrepresented minorities who rise to positions of leadership are less vulnerable to loneliness, or whether they find resources to lessen loneliness.

|

Characteristic

|

n

|

Mean (SD)

|

P

|

|

Overall mean loneliness score

|

108

|

4.75 (1.70)

Range: 3–9

|

N/A

|

|

Mean loneliness score by age

|

.739

|

|

30–39 years

|

4

|

4.50 (1.73)

|

|

|

40–49 years

|

15

|

4.93 (1.67)

|

|

|

50–59 years

|

41

|

4.98 (1.92)

|

|

|

60–69 years

|

38

|

4.63 (1.58)

|

|

|

70 + years

|

9

|

4.22 (1.30)

|

|

|

Mean loneliness score by gender

|

.165

|

|

Male/man

|

70

|

4.57 (1.66)

|

|

|

Female/woman

|

38

|

5.051 (1.79)

|

|

|

Mean loneliness score by underrepresented in medicine status

|

.266

|

|

No

|

83

|

4.84 (1.71)

|

|

|

Yes

|

23

|

4.39 (1.75)

|

|

This study found that loneliness is highest in the 40 to 49 and 50 to 59 age groups, with lower rates after age 60 (Table 2). In contrast to population trends, which show increasing loneliness with age,1 the implication is that a more experienced chair may fare better than their younger colleagues. The decrease in loneliness with age may reflect that with increasing professional experience, chairs gain more trusted colleagues and therefore are better able to mitigate symptoms of loneliness.

In this study, we found no relationship between loneliness and intention to leave the chair role. Intention to leave the role of chair may be better indicated by burnout.14 The rates of burnout are high among family physicians,15,16 and the syndrome of burnout shares several characteristics with loneliness, especially feelings of isolation. Therefore, studying the unique characteristics of loneliness, which are not already accounted for by studying burnout, may be helpful.

Limitations

This study is based on a fixed number of questions (10) added to the CERA survey. Our capacity to fully explore the impact of loneliness and mitigating factors was therefore limited. To explore potential outcomes, we asked about intention to leave the role, a question that could have been difficult to answer for chairs with term-limited appointments. We did not ask about whether chairs were recruited from their own institutions or externally, a distinction that could impact the experience of loneliness. External factors may exist that mitigate feelings of loneliness, such as whether this is their first chair position, they were recruited locally or nationally, they have immediate family members with them, and they identify personal support from friends or colleagues. Distinctions between friends and colleagues, and the relationship of loneliness to burnout require further investigation.

In this study, we found that the majority of family medicine chairs who participated in the CERA survey were experiencing at least one symptom of loneliness in their professional lives and that having trusted colleagues at their home institutions was associated with the mitigation of those symptoms. Further exploration of loneliness in family medicine chairs is warranted and could impact how professional organizations support and develop family medicine leaders (Appendix A).

References

-

Cigna Group. Loneliness in America 2025: A Pervasive Struggle Requires A Communal Response. Cigna Group; 2025.

-

Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):227–237.

-

Hawkley LC, Capitanio JP. Perceived social isolation, evolutionary fitness and health outcomes: a lifespan approach. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2015;370(1669).

-

Park C, Majeed A, Gill H, et al. The Effect of loneliness on distinct health outcomes: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;294:113514.

-

Jung YS, Jung HS, Yoon HH. The effects of workplace loneliness on the psychological detachment and emotional exhaustion of hotel employees. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(9):5228.

-

Bowers A, Wu J, Lustig S, Nemecek D. Loneliness influences avoidable absenteeism and turnover intention reported by adult workers in the United States. J Organ Eff People Perform. 2022;9(2):312–335.

-

Rokach A. Leadership and loneliness. Int J Leadership Change. 2014;2(1):6.

-

Mao H-Y. The relationship between organizational level and workplace friendship. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2006;17(10):1819–1833.

-

Müller F, Charara AK, Holman HT, Achtyes ED. Loneliness among family medicine providers and its impact on clinical and teaching practice. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):15988.

-

Deutch Z, Zvara DA. Lonely at the top? The life of an anesthesia chair. ASA Monitor. 2022;86(11):33–34.

-

Seehusen DA, Mainous AG III, Chessman AW. Creating a centralized infrastructure to facilitate medical education research. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):257–260.

-

Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A Short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: results from two population-based studies. Res Aging. 2004;26(6):655–672.

-

Stokes AC, Xie W, Lundberg DJ, Glei DA, Weinstein MA. Loneliness, social isolation, and all-cause mortality in the United States. SSM Ment Health. 2021;1:1.

-

Ligibel JA, Goularte N, Berliner JI, et al. Well-being parameters and intention to leave current institution among academic physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(12).

-

Freedy JR, Staley C, Mims LD, et al. Social, individual, and environmental characteristics of family medicine resident burnout: a CERA Study. Fam Med. 2022;54(4):270–276.

-

Doe S, Coutinho AJ, Weidner A, et al. Prevalence and predictors of burnout among resident family physicians. Fam Med. 2024;56(3):148–155.