Background and Objectives: The use of large language models and natural language processing (NLP) in medical education has expanded rapidly in recent years. Because of the documented risks of bias and errors, these artificial intelligence (AI) tools must be validated before being used for research or education. Traditional and novel conceptual frameworks can be used. This study aimed to validate the application of an NLP method, bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT) model, to identify the presence and patterns of sentiment in end-of-course evaluations from M3 (medical school year 3) core clerkships at multiple institutions.

Methods: We used the Patino framework, designed for the use of artificial intelligence in health professions education, as a guide for validating the NLP. Written comments from de-identified course evaluations at four schools were coded by teams of two human coders, and human-human interrater reliability statistics were calculated. Humans identified key terms to train the BERT model. The trained BERT model predicted the sentiments of a set of comments, and human-NLP interrater reliability statistics were calculated.

Results: A total of 364 discrete comments were evaluated in the human phase. The range of positive (30.6%–61.0%), negative (4.9%–39.5%), neutral (9.8%–19.0%), and mixed (1.7%–27.5%) sentiments varied by school. Human-human and human-AI interrater reliability also varied by school. Human-human and human-AI reliability were comparable.

Conclusions: Several conceptual frameworks offer models for validation of AI tools in health professions education. A BERT model, with training, can detect sentiment in medical student course evaluations with an interrater reliability similar to human coders.

The use of large language models (LLMs) and natural language processing in medical education has expanded rapidly in recent years.1,2 As artificial intelligence (AI) has become a more common and a more powerful tool, health professions educators find more applications for it, such as creating or editing content, personalization of learning, and data analysis.3,4 A 2023 guide from AMEE (International Association for Health Professions Education) identified several possible applications for artificial intelligence in health professions education (HPE) research, including literature review, data analysis, and qualitative text analysis.5-7

Available tools, such as ChatGPT, are easy for an inexperienced user to engage with, but their methods are opaque.5,8,9 This means that an HPE researcher can input data into an online tool and get an answer, but without knowing how the AI tool arrived at that answer. A lower level of expertise in a clinical content area has been associated with a higher level of trust in AI output, suggesting that a user with less knowledge is more likely to accept an AI response with lower face validity.8,10

AI output is not always reliable, and some errors, particularly hallucinations, can be convincing and difficult to detect.11,12 Fact-checking and triangulating data can validate the output of text generation.13 However, when using AI tools to perform data analysis, the methods and output must be validated if the intention is to use the results to make decisions.14

Validation of an LLM requires both internal validation and verification of the AI tool’s performance, as well as assessment of the validity of the tool’s output. The step of internal validation of the LLM results in an understanding of how accurately the LLM performs after training on a dataset and testing on a second dataset; internal validation measures whether the LLM produces output as expected.9 The assessment of validity for application is often reported as a sensitivity, specificity, or other measure of comparison; this step often uses an accepted gold standard. Various gold standards are used, but consensus exists in medicine that human-based validation is required due to the high stakes of the application of the output.9,15

HPE applications are analogous. The AMEE guide highlighted the importance of validating the AI model and tool being used for HPE research because of the risk of errors and bias.6,8,16-18 One place AI is used in HPE is student course and clerkship evaluations.1,19 Evaluation data are used to make decisions such as faculty promotion and course continuation, which hold substantial stakes for students, faculty, and institutions.

This study presents the validation of a natural language processor (NLP) to identify the presence and patterns of sentiment in end-of-course evaluations from M3 core clerkships at multiple institutions. This study also presents the gold standard analysis: the interrater reliability between human identification of sentiment and LLM identification of sentiment.

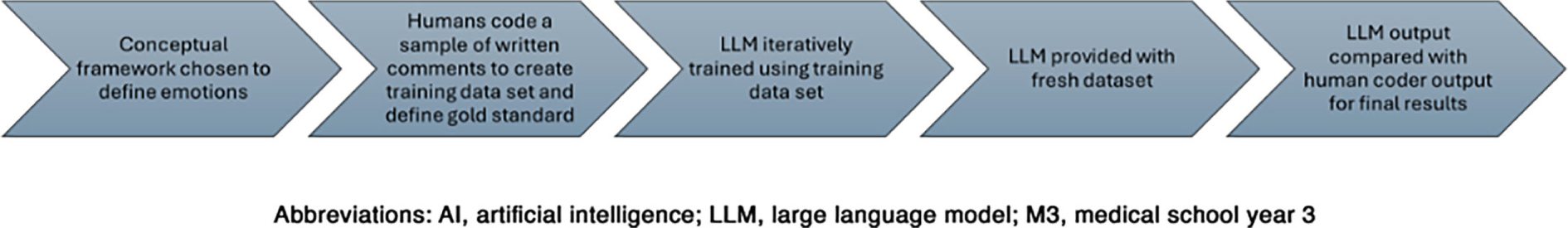

An overview of the steps in the validation of the LLM and its output appears in Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework for Validation

The Messick and Kane models are validation frameworks used in HPE that can be applied to assess the accuracy and reliability of LLM output for text analysis.20 A 2024 article offered a series of questions authors, editors, and readers should consider when approaching a study that uses an AI tool for data analysis.9 These frameworks describe validation of AI tools in the context of HPE (Table 1).

Theory |

Messicka |

Kaneb |

Patinoc |

Main focus |

Unified theory of validity encompassing evidence and consequences |

Argument-based approach to validation |

Data-driven validation focused on model behavior, bias, and robustness |

Key components |

|

|

Dataset provenance and labeling Bias and fairness analysis Generalization and robustness testing Explainability and model transparency |

Validation process emphasis |

Integration of evidence and theoretical rationale |

Construction of interpretive argument and evaluation of inferences |

Empirical evaluation through dataset audits, model performance analysis, error analysis, and interpretability assessments |

Challenges |

Broad; difficult to apply uniformly |

Can be complex to implement fully |

Not yet universally recognized; rapidly evolving field; standards still developing |

Application |

Requires translation from HPE terminology and background to AI-based applications |

Requires translation from HPE terminology and background to AI-based applications |

Requires translation from AI terminology to HPE applications |

Data Analysis

The research team was composed of members from nine US medical schools accredited by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education or the Commission on Osteopathic College Accreditation; each school contributed de-identified course evaluations from core M3 clerkships for the 2022–2023 academic year. The validation dataset included de-identified written comments from four medical schools. Research team members followed institution-specific requirements for obtaining data without identifiable student information. Institutional review board approval or a nonhuman subjects waiver was obtained from each site.

Identification of the Sentiment Framework

Based on a review of the literature, the research team determined three potential frameworks to identify sentiment in written text: the Feelings Wheel, Plutchik’s Wheel of Emotions, and the Emotoscope Feelings Chart.21-23 These were each assessed for completeness and accuracy of emotions in a sample of written comments from each school using a separate validation process not reported here. Based on this assessment, the Feelings Wheel was identified as the preferred framework.

Identification of the Gold Standard

A sample of written comments from each of the four pilot schools was included in the validation sample. Teams of two human coders completed two rounds of coding using the Feelings Wheel framework. Each team of two coders independently coded comments from two schools. Each round included comments from 20 respondents from each school. Different schools used different prompts, and students wrote responses of varying length and content. Thus, 20 written responses could result in multiple instances of sentiment, resulting in uneven numbers of comments identified from the responses. For example, the prompt “What was the best aspect of this clerkship?” generated a single response: “Resident clinic was a valuable learning experience, and community preceptors demonstrate a passion for teaching students.” This would be analyzed as two comments: Resident clinic was a valuable learning experience. And, separately, community preceptors demonstrate a passion for teaching students.

The coders independently identified a primary sentiment: positive, negative, neutral, or no sentiment, and, for comments with a positive or negative primary sentiment, a secondary sentiment (Table 2). The coders then discussed discrepancies with a goal of improving future consistency. During this process, coders also identified the specific words from the written comments that signaled sentiments. The intention with two human codings was twofold: to create a gold standard for the definition of the sentiment terms as applied to the dataset, and to provide specific information for training the LLM. Interrater reliability metrics were calculated between human coders using Fleiss’ κ.

Example |

Primary sentiment |

Secondary sentiment |

“Working in the … clinic was the best aspect of this clerkship where I feel like I learned the most practical and applicable material.” |

Positive |

Proud |

“Hit or miss rotations. Some students shadow, others perform procedures.” |

Neutral |

N/A |

“The amount of time provided to complete the OSCE. Specifically the note write-up was an issue for myself and every peer that I talked with.” |

Negative |

Angry |

“Really cool to learn about [skill], but sometimes I kind of zoned out.” |

Mixed |

Joyful

Disgusted |

Large Language Model

We used different generations and varying sizes of LLMs. These included the bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT) family of models, which are primarily trained using the masked language modeling paradigm, as well as generative language models trained auto-regressively. The generative language models showed more capabilities in zero-shot and few-shot in-context learning, which made them a strong basis for further modeling and domain-specific improvements. A traditional BERT model was selected because it is a pretrained model and lighter version. It can be run locally without using too many computer resources, while other models, such as RoBERTa, are reserved for large datasets and have longer training time. We opted against a generative AI model such as ChatGPT or Gemini in order to use a model compliant with the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA).

The results of the human-identified gold standard were then used to train the LLM to identify primary and secondary sentiments. We trained BERT for sentiment prediction with the following steps: (1) preparing labeled data, (2) tokenizing with BERT’s tokenizer, (3) fine-tuning a pretrained BERT model with a classification head, and (4) evaluating with accuracy/F1 metrics.

Validation of the Sentiment

After two human coders established the gold standard for the definition of the sentiment, the LLM was trained on the gold standard. The LLM then independently coded a separate validation sample of 20 responses per school. Two teams of two human coders each also coded the same validation dataset (20 responses per school, with each team responsible for two schools). Interrater reliability between the LLM and the human coders was quantified using Fleiss’ κ to evaluate the model’s performance relative to human raters.

A total of 364 discrete comments were evaluated. Significant variations existed in the total number of comments (range 40–162) per school and the number and percentage of sentiments identified by human coders. The range of positive (30.6%–61.0%), negative (4.9%–39.5%), neutral (9.8%–19.0%), and mixed (1.7%–27.5%) sentiments varied by school (Table 3). Human-human and human-AI interrater reliability also varied by school (range of Fleiss’s k: 0.658–1). In aggregate, human-human and human-AI agreement were comparable (range of Fleiss’s k: 0.640–0.945 (Table 4).

|

School

|

Total

N

|

Positive

n (%)

|

Neutral

n (%)

|

Negative

n (%)

|

Mixed

n (%)

|

N/A

n (%)

|

|

School 1

|

121

|

37 (30.6)

|

41 (33.9)

|

23 (19.0)

|

2 (1.7)

|

22 (18.2)

|

|

School 2

|

162

|

49 (30.2)

|

64 (39.5)

|

23 (14.2)

|

4 (2.5)

|

9 (5.6)

|

|

School 3

|

41

|

25 (61.0)

|

2 (4.9)

|

4 (9.8)

|

10 (24.4)

|

1 (2.4)

|

|

School 4

|

40

|

23 (57.5)

|

3 (7.5)

|

5 (12.5)

|

11 (27.5)

|

0

|

|

Combined

|

364

|

134 (36.8)

|

110 (30.2)

|

55 (15.1)

|

27 (7.4)

|

32 (8.8)

|

Primary sentiment |

Fleiss’ κ |

95% CIs |

Secondary sentiment |

Fleiss’ κ |

95% CIs |

Human-human |

School 1 |

1 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

School 1 |

0.732 |

0.620 |

0.843 |

School 2 |

0.658 |

0.536 |

0.779 |

School 2 |

0.352 |

0.265 |

0.439 |

School 3 |

0.904 |

0.686 |

1.121 |

School 3 |

0.431 |

0.243 |

0.618 |

School 4 |

0.960 |

0.753 |

1.166 |

School 4 |

0.352 |

0.181 |

0.522 |

All four schools |

0.845 |

0.773 |

0.917 |

All four schools |

0.537 |

0.476 |

0.597 |

AI vs annotator 1 (AN1) |

AI vs AN1

School 1 |

0.951 |

0.808 |

1.000 |

AI vs AN1-School 1 |

0.879 |

0.759 |

0.999 |

AI vs AN1

School 2 |

0.929 |

0.791 |

1.000 |

AI vs AN1-School 2 |

0.657 |

0.522 |

0.791 |

AI vs AN1

School 3 |

1 |

1.000 |

1.000 |

AI vs AN1-School 3 |

0.869 |

0.692 |

1.000 |

AI vs AN1

School 4 |

0.843 |

0.618 |

1.000 |

AI vs AN1-School 4 |

0.893 |

0.668 |

1.000 |

All four schools |

0.945 |

0.866 |

1.000 |

All four schools |

0.888 |

0.819 |

0.958 |

AI vs annotator 2 (AN2) |

AI vs AN2

School 1 |

0.951 |

0.808 |

1.000 |

AI vs AN2-School 1 |

0.697 |

0.576 |

0.817 |

AI vs AN2

School 2 |

0.864 |

0.752 |

0.976 |

AI vs AN2-School 2 |

0.478 |

0.359 |

0.597 |

AI vs AN2

School 3 |

0.904 |

0.686 |

1.000 |

AI vs AN2-School 3 |

0.475 |

0.282 |

0.668 |

AI vs AN2

School 4 |

0.794 |

0.570 |

1.000 |

AI vs AN2-School 4 |

0.640 |

0.407 |

0.872 |

All four schools |

0.845 |

0.766 |

0.923 |

All four schools |

0.640 |

0.566 |

0.714 |

We found that a trained LLM could identify sentiment in written comments from student end-of-clerkship evaluations with a similar interrater reliability to human coders. We observed considerable variability across institutions in sentiment distribution and interrater reliability, but the summary data showed acceptable validity. This study provides an example of the validation process for an AI tool from both the artificial intelligence and the human application perspectives.

Our approach started with determining human gold standard of sentiment identification through multiple rounds of coding before introducing an AI component. This initial step served as a benchmark to compare against the AI output, rather than assuming AI accuracy from the start. This approach to validation can be used as a framework for other educational researchers who plan to use AI tools.

AI Tools in HPE

One identified flaw of the use of LLMs is that the patterns of errors and biases in any given tool and dataset are unknown.24 When interpreting data created or analyzed using AI, the AI tool must be trained and validated on the dataset being analyzed. This step ensures that the inputs and analysis provide reproducible, predictable, and transparent results. Previous studies have shown heterogeneous evidence of validation prior to the use of LLMs in medical research.25

AI tools are particularly appealing when the volume of data is large and when existing methods for handling the data would be cumbersome.26 This savings is reasonable only if the output is also valid: if the results afford meaningful contributions to decision-making.27 The correct AI tool must also be selected. Our choice of LLM was based on factors including its ability to perform the analysis, use of computing resources, and FERPA compliance. FERPA compliance was a strong factor in the selection of BERT; we used an internal model that did not collect or share data. At the time of the analysis, this was not a universal feature on most generative LLMs, and for privacy and safety reasons, we considered it essential.

Course evaluation data often includes both numeric and written comment data, which is often copious in volume. Thus, these data are a tempting target for LLM application. Student course evaluations are used for faculty promotion and impact curriculum decisions.28,29 Given the stakes inherent in the process of course evaluation, ensuring reliable output is critical.

Validation

The goal of validation is high-quality decision-making, which requires a reliable tool and useful, accurate output.8,30 Our study demonstrated the use of several best practices for using LLMs in medical education research. Many purported uses of AI in medical education train the model but omit the step of testing the output, employing an empirical trust of the AI training process.9 The potential consequences of forgoing validation include a threat to the validity of both the method of analysis and the outcomes themselves.31,32 Human-based validation is essential in establishing the LLM’s reliability and generalizability when applied to high-stakes decisions.

Interdisciplinary Collaboration

Interprofessional collaboration is expected in HPE. This study required experience and expertise in a range of areas. HPE faculty have the background in theory and provide the conceptual foundation; clinical faculty support the practical interpretation and implementation; and statistics experts provide methodological and analytic direction. The research team included members with backgrounds in HPE, clinical medicine, and statistics, including expertise in LLMs. As AI becomes more mainstream and is integrated thoughtfully and rigorously into HPE research and practice, high-quality research will require more collaboration of this kind.33 Similarly, HPE researchers will need to be familiar with AI tools and techniques as they become more common in the literature and in practice.

Limitations

Our evaluation has several significant limitations. This study coded for the researchers’ interpretation of student comments. Because we were using a de-identified data set, we were not able to ask students directly what their emotions were at the time they completed the clerkship evaluations. That would be the true gold standard.

Future Directions

While our pilot study demonstrated the feasibility of using LLMs for emotional analysis in end-of-course evaluations, it also highlighted the need for more research on this topic. With the results of this pilot study, we intend to train the NLP models with human annotations to more precisely and accurately identify emotional language relevant to medical education, our dataset, and the chosen frameworks.

With training, AI tools detect sentiment in medical student course evaluations with an interrater reliability similar to human coders.

This work was presented at the Association of American Medical Colleges meeting, October 2024, Atlanta, Georgia.

References

-

Parente DJ. Generative artificial intelligence and large language models in primary care medical education.

Fam Med. 2024;56(9):534–540. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2024.775525

-

Jackson P, Ponath Sukumaran G, Babu C, et al. Artificial intelligence in medical education - perception among medical students.

BMC Med Educ. 2024;24(1). doi:10.1186/s12909-024-05760-0

-

Xu T, Weng H, Liu F, et al. Current status of ChatGPT use in medical education: potentials, challenges, and strategies.

J Med Internet Res. 2024;26(1). doi:10.2196/57896

-

Domrös-Zoungrana D, Rajaeean N, Boie S, Fröling E, Lenz C. Medical education: considerations for a successful integration of learning with and learning about AI.

J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2024;11. doi:10.1177/23821205241284719

-

Sallam M. ChatGPT utility in healthcare education, research, and practice: systematic review on the promising perspectives and valid concerns.

Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(6). doi:10.3390/healthcare11060887

-

Tolsgaard MG, Pusic MV, Sebok-Syer SS, et al. The fundamentals of artificial intelligence in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 156.

Med Teach. 2023;45(6):565–573. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2023.2180340

-

Gwon YN, Kim JH, Chung HS, et al. The use of generative ai for scientific literature searches for systematic reviews: ChatGPT and Microsoft bing AI performance evaluation.

JMIR Med Inform. 2024;12. doi:10.2196/51187

-

Nguyen T. ChatGPT in medical education: a precursor for automation bias?

JMIR Med Educ. 2024;10. doi:10.2196/50174

-

Patino GA, Amiel JM, Brown M, Lypson ML, Chan TM. The promise and perils of artificial intelligence in health professions education practice and scholarship.

Acad Med. 2024;99(5):477–481. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000005636

-

Gaube S, Suresh H, Raue M, et al. Do as AI say: susceptibility in deployment of clinical decision-aids.

NPJ Digit Med. 2021;4(1). doi:10.1038/s41746-021-00385-9

-

Zhou J, Zhang J, Wan R, et al. Integrating AI into clinical education: evaluating general practice trainees’ proficiency in distinguishing AI-generated hallucinations and impacting factors.

BMC Med Educ. 2025;25(1). doi:10.1186/s12909-025-06916-2

-

Burford KG, Itzkowitz NG, Ortega AG, Teitler JO, Rundle AG. Use of generative AI to identify helmet status among patients with micromobility-related injuries from unstructured clinical notes.

JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(8). doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.25981

-

DeVerna MR, Yan HY, Yang KC, Menczer F. Fact-checking information from large language models can decrease headline discernment.

Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024;121(50). doi:10.1073/pnas.2322823121

-

Májovský M, Černý M, Kasal M, Komarc M, Netuka D. Artificial intelligence can generate fraudulent but authentic-looking scientific medical articles: pandora’s box has been opened.

J Med Internet Res. 2023;25(1). doi:10.2196/46924

-

Tam TYC, Sivarajkumar S, Kapoor S, et al. A framework for human evaluation of large language models in healthcare derived from literature review.

NPJ Digit Med. 2024;7(1). doi:10.1038/s41746-024-01258-7

-

Celi LA, Cellini J, Charpignon M-L, et al. Sources of bias in artificial intelligence that perpetuate healthcare disparities-A global review.

PLOS Digit Health. 2022;1(3). doi:10.1371/journal.pdig.0000022

-

Hasanzadeh F, Josephson CB, Waters G, Adedinsewo D, Azizi Z, White JA. Bias recognition and mitigation strategies in artificial intelligence healthcare applications.

NPJ Digit Med. 2025;8(1). doi:10.1038/s41746-025-01503-7

-

-

Annan SL, Tratnack S, Rubenstein C, Metzler-Sawin E, Hulton L. An integrative review of student evaluations of teaching: implications for evaluation of nursing faculty.

J Prof Nurs. 2013;29(5):e10–24. doi:10.1016/j.profnurs.2013.06.004

-

Carrillo-Avalos BA, Leenen I, Trejo-Mejía JA, Sánchez-Mendiola M. Bridging validity frameworks in assessment: beyond traditional approaches in health professions education.

Teach Learn Med. 2025;37(2):229–238. doi:10.1080/10401334.2023.2293871

-

Willcox G. The feeling wheel: a tool for expanding awareness of emotions and increasing spontaneity and intimacy.

Transactional Anal J. 1982;12(4):274–276. doi:10.1177/036215378201200411

-

Plutchik R, Kellerman H. Theories of Emotion. Academic Press; 1980.

-

-

Akyon SH, Akyon FC, Camyar AS, Hızlı F, Sari T, Hızlı Ş. Evaluating the capabilities of generative AI tools in understanding medical papers: qualitative study.

JMIR Med Inform. 2024;12. doi:10.2196/59258

-

Siontis GCM, Sweda R, Noseworthy PA, Friedman PA, Siontis KC, Patel CJ. Development and validation pathways of artificial intelligence tools evaluated in randomised clinical trials.

BMJ Health Care Inform. 2021;28(1). doi:10.1136/bmjhci-2021-100466

-

Xu Y, Liu X, Cao X, et al. Artificial intelligence: a powerful paradigm for scientific research.

Innovation (Camb). 2021;2(4). doi:10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100179

-

-

Stroebe W. Student evaluations of teaching encourages poor teaching and contributes to grade inflation: a theoretical and empirical analysis.

Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2020;42(4):276–294. doi:10.1080/01973533.2020.1756817

-

Wahlqvist M, Skott A, Björkelund C, Dahlgren G, Lonka K, Mattsson B. Impact of medical students’ descriptive evaluations on long-term course development.

BMC Med Educ. 2006;6(1). doi:10.1186/1472-6920-6-24

-

Russell M. Clarifying the terminology of validity and the investigative stages of validation.

Educational Measurement. 2022;41(2):25–35. doi:10.1111/emip.12453

-

Marceau M, Young M, Gallagher F, St-Onge C. Eight ways to get a grip on validity as a social imperative.

Can Med Educ J. 2024;15(3):100–103. doi:10.36834/cmej.77727

-

Marceau M, Gallagher F, Young M, St-Onge C. Validity as a social imperative for assessment in health professions education: a concept analysis.

Med Educ. 2018;52(6):641–653. doi:10.1111/medu.13574

-

Lomis K, Jeffries P, Palatta A, et al. Artificial intelligence for health professions educators.

NAM Perspect. 2021;2021. doi:10.31478/202109a

There are no comments for this article.