Over the past 2 decades, the growing need to strengthen primary care in southern Africa has fueled a rising interest in the specialty of family medicine. Given the region’s heavy burden of both communicable and noncommunicable diseases, along with restricted health care resources and limited access to care, family physicians may play a key role in improving health care access and quality in these settings. The development of family medicine in Zambia began in 2013 as a working group of committed clinical and public health academics, and progressed to the launch of that country’s first family medicine residency in 2019. Despite enormous challenges, the program has flourished since that time, growing rapidly from the inaugural two residents in 2019 to 45 residents and recent graduates by 2025. While this growth has allowed the residency to become a leader in family medicine education in the region, it also has brought a new set of challenges. In this narrative, we describe the health care context of Zambia, the introduction of family medicine as a specialty to a new health care landscape, and the launch of that country’s first ever and rapidly growing family medicine residency, as well as unique challenges, strategies employed, and lessons learned along the way. We conclude the article by looking ahead at new challenges and recommendations for the program’s continued growth. The experiences and lessons learned may be used by future family medicine residency start-ups throughout sub-Saharan Africa.

Over the past 2 decades, the growing need to strengthen primary care in southern Africa has fueled a rising interest in the specialty of family medicine. Traditionally, health care systems in the region have relied heavily on large urban hospitals staffed by specialists—a model that has proven inefficient in addressing the evolving health landscape. 1, 2 In this highly centralized system, specialists are rare outside of major cities, and rural health care is largely delivered by generalists with minimal postgraduate training or other nonphysician clinicians who are expected to provide care with minimal resources or support. 3 As the burden of both communicable and noncommunicable diseases has surged, and the necessity of decentralizing care—particularly in rural areas—has become more pressing, the urgency of reinforcing primary care has never been clearer. In response, family medicine has emerged as a cornerstone strategy for a more effective and equitable health care system in this region.

The unique role of family physicians in providing care in southern Africa is highlighted by the region’s high disease burden, limited resources, and fractured care delivery, as well as significant access to care obstacles, especially in rural areas. Family medicine as practiced in many settings in Africa has a broad scope, is more surgically oriented than family medicine in most global north settings, and includes core areas of internal medicine, pediatrics, general surgery, and obstetrics and gynecology. In the African health care context, family physicians trained to provide comprehensive, continuous, and community-oriented care have an opportunity to provide holistic, patient-centered care closer to the patients’ home—a benefit rarely offered by other specialties in this setting.

For these reasons family medicine has experienced significant growth in southern Africa over the past few decades. South Africa was among the first countries on the continent to integrate family medicine into postgraduate training programs across multiple universities, and today its programs remain the most well-established on the continent. Meanwhile, universities in Botswana, Malawi, Zambia, and Zimbabwe have developed family medicine training programs at various stages of maturity, reflecting a broader commitment to strengthening primary care in the region.

Alongside these academic advancements, national family medicine professional associations and regional networks have expanded, supported by donors and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). In 2024, this momentum led to the establishment of the College of Family Physicians of East, Central, and Southern Africa (ECSA-CFP), a key initiative aimed at unifying and standardizing the specialty while fostering knowledge exchange and resource sharing across the region.

As family medicine training programs expanded and early challenges were addressed, governments across the region increasingly recognized the specialty as a strategic investment in building a high-quality primary care workforce. In response, several national regulatory bodies formally recognized family medicine as a distinct specialty, and its integration into government human resources for health strategic plans gained momentum. In Zambia, for instance, the Ministry of Health’s (MoH’s) 2019 Operational Training Plan marked a significant milestone by calling for the rapid establishment of three family medicine training programs nationwide—an important step toward institutionalizing and scaling up the specialty.

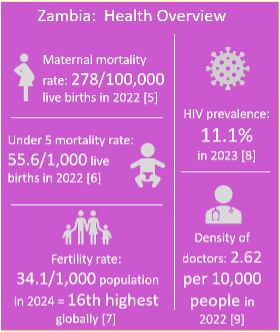

Despite significant progress in recent years, Zambia, located in the southern Africa region, shares many of the significant health burdens of its neighbors (Figure 1, Figure 2). In 2022, the country’s mortality rate for children under 5 years of age was 55.6/1,000 live births, and its maternal mortality rate was 278/100,000 live births (as compared to 6.3/1,000 and 22.3/100,000, respectively, in the United States). 4-6 Zambia still carries one of the highest birth rates globally. 7 In this health care context, Zambia has been at the forefront of family medicine growth, making significant strides in integrating family medicine into postgraduate and undergratuate training. The Zambian government’s commitment to strengthening primary care is reflected in policy frameworks that prioritze family medicine in health care delivery.

DEVELOPMENT OF FAMILY MEDICINE IN ZAMBIA

Early Development: Challenges and Progress

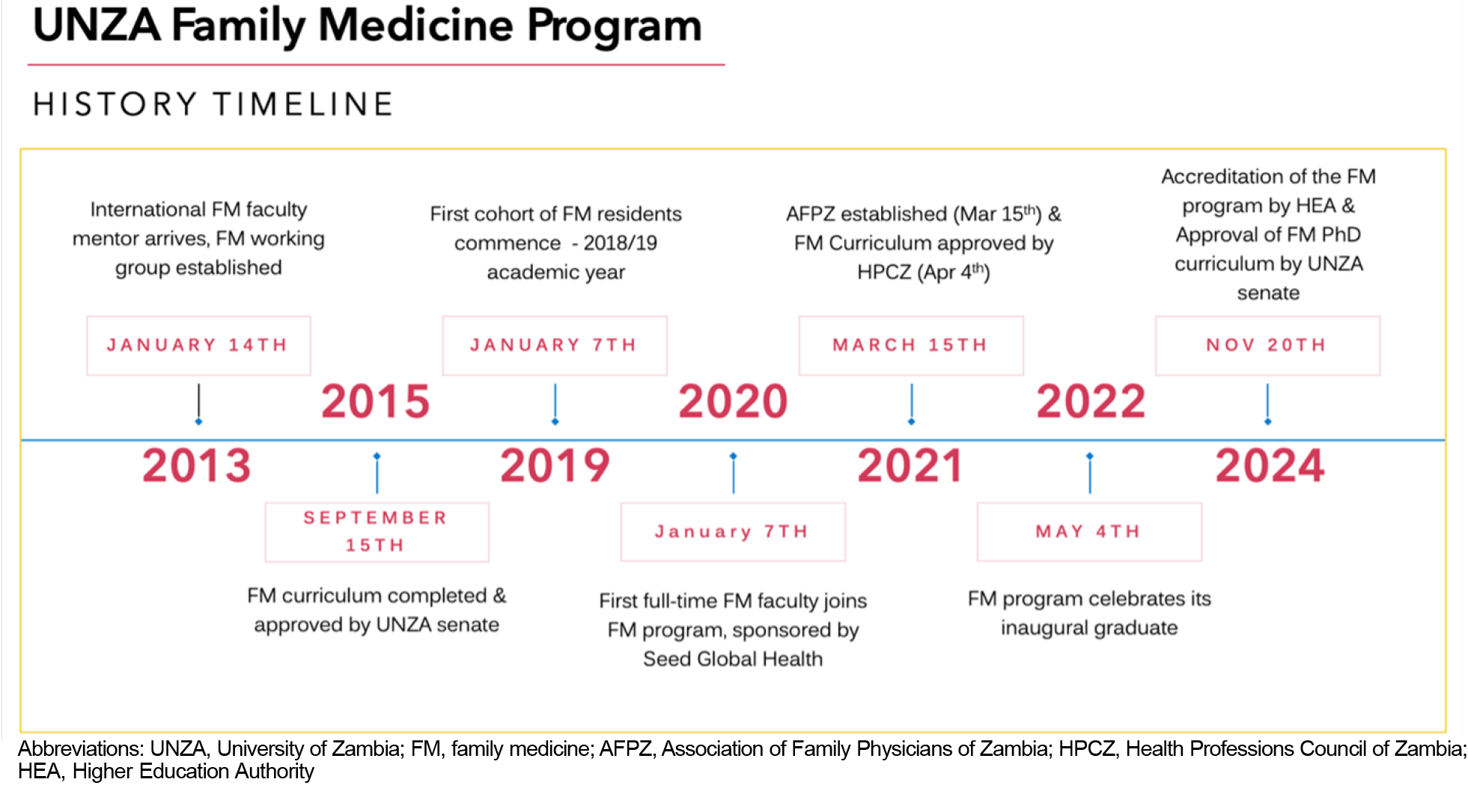

Recognizing the need for improved primary care services and the unique role family medicine could play, the University of Zambia (UNZA) introduced primary care training at the graduate level in the early 1990s. 8 This initial attempt was brief. Given that the specialty was not yet recognized by Zambia’s MoH, while also not being linked to the internationally recognized specialty of family medicine, career aspects were dim, and many of the original residents left the program, which subsequently collapsed. In 2012, the idea of a family medicine training program resurfaced, and in 2013 UNZA formed a family medicine working group. An early obstacle was the complete lack of any preexisting expertise in the specialty of family medicine or its development; so the working group invited an academic family physician from the United States, sponsored by a Fulbright Scholarship, to travel to Zambia for 12 months to chair the group. Under this mentorship, initial strategies were developed and implemented, including an initial needs assessment—which reaffirmed the need for a family medicine program in Zambia—while also initiating curriculum development and advocating for recognition of the specialty at the Zambian MoH. 3, 8, 9 Because this latter body had no previous experience with family medicine, the working group chose to introduce basic concepts of family medicine first while also highlighting family medicine’s successful introduction into other African countries’ health care landscapes. In seeking additional support for its advocacy efforts, the working group also chose to collaborate with the Primary Care and Family Medicine Network for sub-Saharan Africa (PRIMAFAMED), a network of academic family physicians that strengthens family medicine education throughout Africa, which offered mentorship and support during this critical time. The climax of its advocacy efforts came in 2014, when a stakeholder meeting was held in Lusaka, bringing together physicians, representatives from Zambia’s Health Professions Council of Zambia (HPCZ), and the Zambian MoH. In this meeting, the definition of a Zambian family physician was detailed, their role in the Zambian health care system was defined, and an initial family medicine residency curriculum was proposed. 1 This meeting led to full recognition of family medicine as a specialty by the Zambian MOH in 2014. A full description of the working group’s activities has been published previously. 3, 9

Residency Launch: New Obstacles and Strategies

In 2015, the inaugural family medicine residency curriculum was submitted to and approved by UNZA’s University Senate. In 2019, the Zambian MoH established training goals for Zambian family medicine residents. The program’s first two residents were recruited and started the program in early 2019. While initial faculty included two part-time, internationally trained family physicians working in private practice in Lusaka, in 2019 UNZA partnered with Seed Global Health (Seed), a US-based, philanthropically funded NGO committed to the growth of Africa’s human resources for health by sending educators to strengthen medical education in that region. Seed sponsored the program’s first full-time faculty, who arrived on-site in January 2020, and hired its first Zambian country director the same year. In 2022, Seed expanded its support by sponsoring two full-time family medicine faculty for the program.

In these initial years, similar to other new family medicine programs in Africa, the fledgling program faced enormous obstacles. 10 Its existing curriculum was found to be more theoretical than practical. In response, faculty met regularly with the program’s two residents in 2020 to rework the curriculum, combining elements of family medicine curricula from South Africa and the United States and contextualizing to the health care landscape of Zambia. The program initially had no dedicated facilities, so faculty advocated for a classroom at UNZA School of Public Health and eventually garnered funds from Seed to revitalize this space. The program had no administrative support, so initially faculty managed all administrative needs while also advocating for funds for a part-time administrative position, which Seed later funded. Family medicine wasn’t recognized as a specialty by many colleagues at the program’s clinical sites, so faculty prioritized in-person meetings and collegial relationships with hospital leaders to advocate for the family medicine residents and the program’s needs. Recognizing the quality of education the family medicine residents were receiving and their health care delivery, hospital colleagues began to view family physicians as the go-to specialists when complicated patient cases arose. The program was housed in the UNZA School of Public Health, which had no previous experience managing a clinical residency, so faculty met with leaders from the UNZA School of Medicine and adapted some of their strategies for program management. In 2020, faculty discovered the existence of two separate medical education credentialing bodies in Zambia—HPCZ and the Zambian Higher Education Authority (HEA), and which credentialing body was more appropriate for the residency was unclear. Family medicine faculty sought advice from other Zambian residencies and chose to submit to HPCZ first, while later submitting to HEA as well in 2022. COVID-19 struck Zambia in April 2020, and UNZA family medicine’s main clinical site was transitioned to a COVID-19 isolation hospital later that year. In response, family medicine faculty continued regular program didactics virtually, shifted some rotations to other facilities so the residents’ education could continue, and committed a rotating cohort of family medicine residents to the COVID-19 isolation unit. Amazingly, the program’s didactics continued seamlessly throughout the thrust of COVID-19, and none of the residents’ progress was delayed. However, with growth of both the program and its patient population, faculty were stretched thin. In response, several part-time faculty (both family medicine and other specialties) were utilized, a resident-led didactic series was implemented, and family medicine faculty advocated for Seed to support a second full-time faculty position, which was granted in 2022. Throughout all of this, family medicine faculty learned that regular meetings with a small group of committed colleagues—in this case, a group of the program’s inaugural faculty and residents—as well as flexibility and persistent advocacy were invaluable components of the program’s success in overcoming this array of obstacles.

Recent Growth: Expanding Boundaries

Since its launch, UNZA family medicine has seen unprecedented growth and achieved multiple significant milestones. Its pool of residents has grown immensely, from the original two to a current total of 45 residents, either in training or recently graduated, over the last 6 years—growth exceeding that of many other African family medicine programs. 11 UNZA family medicine has quickly become one of UNZA’s most popular residency programs, and the program now has to turn away applicants during its annual recruitment season. Residents regularly cite the quality of education (specifically the high-yield nature of didactics, ample face-to-face time with faculty, and positive learning environment/approachability of faculty—all of which they report as rare among Zambia’s residency programs) and versatility of the specialty as major draws to the program. In addition, 2021 was a notable year for the program, which saw its curriculum approved by HPCZ and the founding of Zambia’s first family medicine professional society, the Association of Family Physicians of Zambia (AFPZ). In 2022, the program established Zambia’s first family medicine medical school rotation with students from Levy Mwanawasa Medical University, while also celebrating its first-ever resident graduate. In 2024, UNZA family medicine’s curriculum was approved by Zambia’s HEA, UNZA School of Public Health created its first funded family medicine faculty position, and a curriculum for a PhD in family medicine was approved by UNZA’s University Senate (Figure 3).

At the time of this writing, UNZA family medicine has 40 family medicine residents distributed throughout its 4-year program, with a total of five graduates—all of which are still involved with the program as faculty to varying degrees (Figure 4). Residents get 6 hours of didactics per week, taught by a mix of family medicine faculty, speakers from other specialties, and the residents themselves. Didactics occur at a recently refurbished classroom allotted to the program by UNZA School of Public Health, while clinical duties occur at one of two community hospitals in Lusaka. Given its rapid growth, the program now faces a new set of challenges, including upkeep of education quality, the need for additional faculty, mentorship of graduates as they transition to faculty, and employment prospects for new graduates. Nonetheless, the program is emerging as a family medicine leader in the region, with plans to host a PRIMAFAMED conference, provide leaders to the recently formed ECSA-CFP, and host cross-country collaborations with the family medicine program in neighboring Malawi. While family medicine as a specialty is now recognized by the Zambian MoH, and its role has been defined historically,3 uncertainty remains as to what role family medicine will play in the larger Zambian health care system in the coming years.

Considering this growth, many challenges remain. Growing numbers of residents may compromise education quality. Indeed, growth in resident numbers has far outpaced that of faculty positions, diluting the resident-to-faculty ratio and spreading faculty thin. This same growth is problematic in other ways, including congested rotations and inadequate meeting space. Another challenge is one experienced by most family medicine residencies in resource-limited settings, namely the discrepancy between what is taught (the textbook standard) and what can practically be performed with such limited health care resources. Also, while the program has graduated its first residents and would seek to recruit them as faculty, a need for faculty development has emerged that is not easy to fill. Finally—and perhaps most existentially—the question of whether the Zambian MoH will fund positions for family physicians and exactly what capacity those positions will entail are yet to be seen.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PROGRESS

Multiple strategies may be considered to ensure that the specialty of family medicine will thrive in the Zambian health care context. First, as mentioned earlier, faculty development is an emerging need. Ideally, this would involve mentorship—either in person, remotely, or both—by another, more experienced family medicine educator; and its components would be consistent with previously published guidelines. 12 In addition, faculty development could be integrated into the program for faculty-bound residents even prior to graduation.12 For UNZA family medicine, next steps toward faculty development may include implementing a schedule of virtual sessions with a seasoned family medicine educator experienced in faculty development, or potentially looking to hire such a candidate through one of its partnerships, such as Seed.

To be more widely recognized in Zambia, family medicine also will need to expand its footprint to additional health care facilities. Recently, MoH leaders have expressed interest in the possibility of expanding the UNZA family medicine program to other district-level health care facilities in Lusaka, a move likely necessary for the growth of the specialty. 13 If this growth were to occur, UNZA family medicine would attempt to have new graduates posted at these facilities so that faculty supervision would be available in-house, while residents would still meet at the program’s central location for didactics and other program meetings. Given family medicine’s suitability for rural contexts in Africa, 14 the program has a newly established rural training site where residents will begin rotating in 2025. All expansion must be handled in a way that allows for growth without compromising faculty oversight and education quality.

Ongoing discussions with Zambia’s health care leadership will be needed to further define family medicine’s role in the Zambian health care context. Family physicians have been recognized as the ideal leaders of an African district-level hospital, 13 but family medicine’s role in this setting—despite being defined historically 3—will need to be clarified. 15 Further advocacy also will be required for the creation of future family medicine positions at district-level hospitals, as has been achieved elsewhere in the region. 16

In 2024, faculty from UNZA family medicine met for the first time with family medicine faculty from Malawi’s Kamuzu University of Health Sciences for a 2-day conference of knowledge sharing and problem-solving. This experience was highly beneficial to both groups, and UNZA family medicine realized the value of cross-country family medicine collaborations. As with previous South-South collaborations, 17, 18 UNZA family medicine likely will be pursuing collaborations with other regional family medicine programs for knowledge sharing, research collaborations, and possibly away electives for its residents.

To better integrate family medicine into the Zambian medical education system—and improve long-term recruitment of trainees—UNZA family medicine likely will seek to expand family medicine’s footprint in the country’s medical schools. To promote widespread recognition of family medicine as an established medical specialty in Zambia, UNZA family medicine will need to expand its clerkship offerings to all of Zambia’s major medical schools, including UNZA’s own school of medicine. Given the number of schools and large class sizes, UNZA family medicine will have to approach this expansion strategically to avoid overwhelming faculty and diluting education quality.

AFPZ has grown significantly and continues to advocate for family medicine’s wider recognition in Zambia’s health system. UNZA family medicine will need to continue to collaborate closely with AFPZ and encourage residents’ early involvement and ascent to leadership. 16 By fostering the value of advocacy among its trainees early on, UNZA family medicine hopes to inspire a pattern of lifelong advocacy for the specialty of family medicine among its graduates.

Finally, UNZA family medicine will continue to expand its research footprint. Primary care literature in the Zambian context is scarce, and the program has the opportunity to be an academic leader in this field. The program already has integrated research into its curriculum, with training in research methods and a required research project for all residents; next steps will include seeking external funding for projects and collaborations with other academic family medicine programs in the region. Research is urgently needed to better enable family medicine to meet Zambia’s current health care needs, demonstrate family medicine’s impact on the Zambian health system, and optimize family medicine education in the Zambian context. 15, 19

Although still in its infancy, Zambia’s first family medicine residency has grown dramatically. Evolving priorities will need to emphasize education quality in the face of program expansion, mentorship of locally trained faculty, and persistent advocacy to better integrate family medicine into the wider Zambian health care context.

The authors thank Seed Global Health and University of Zambia for their continuing support of the UNZA Family Medicine program.

Presentations

This study was presented at the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference, May 1, 2023, in Tampa, Florida.

References

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Makasa M, Nzala S, Sanders J. Developing family medicine in Zambia.

Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2015;7(1):909.

doi:10.4102/phcfm.v7i1.909

-

Sanders J, Makasa M, Goma F, Kafumukache E, Ngoma MS, Nzala S. A quick needs assessment of key stakeholder groups on the role of family medicine in Zambia.

Afr J Health Prof Educ. 2017;9(3):94.

doi:10.7196/AJHPE.2017.v9i3.831

-

Gossa W, Wondimagegn D, Mekonnen D, Eshetu W, Abebe Z, Fetters M. Key informants’ perspectives on development of family medicine training programs in Ethiopia.

Adv Med Educ Pract. 2016;7:261-269.

doi:10.2147/AMEP.S94522

-

Momanyi K, Dinant GJ, Bouwmans M, Jaarsma S, Chege P. Current status of family medicine in Kenya; family physicians’ perception of their role.

Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2020;12(1):e1-e4.

doi:10.4102/phcfm.v12i1.2404

-

-

Moosa S, Downing R, Essuman A, Pentz S, Reid S, Mash R. African leaders’ views on critical human resource issues for the implementation of family medicine in Africa.

Hum Resour Health. 2014;12(1):2.

doi:10.1186/1478-4491-12-2

-

Makwero M, Lutala P, McDonald A. Family medicine training and practice in Malawi: history, progress, and the anticipated role of the family physician in the Malawian health system.

Malawi Med J. 2017;29(4):312-316.

doi:10.4314/mmj.v29i4.6

-

Flinkenflögel M, Sethlare V, Cubaka VK, Makasa M, Guyse A, De Maeseneer J. A scoping review on family medicine in sub-Saharan Africa: practice, positioning and impact in African health care systems.

Hum Resour Health. 2020;18(1):27.

doi:10.1186/s12960-020-0455-4

-

-

Flinkenflögel M, Essuman A, Chege P, Ayankogbe O, De Maeseneer J. Family medicine training in sub-Saharan Africa: South-South cooperation in the PRIMAFAMED project as strategy for development.

Fam Pract. 2014;31(4):427-436.

doi:10.1093/fampra/cmu014

-

-

Von Pressentin KB, Besigye I, Mash R, Malan Z. The state of family medicine training programmes within the primary care and family medicine education network.

Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2020;12(1):e1-e5.

doi:10.4102/phcfm.v12i1.2588

There are no comments for this article.