Background and Objectives: The family medicine clerkship has been found to influence medical students’ decision-making regarding specialty choice. Understanding how the family medicine clerkship has changed over the past decade may assist in recruitment efforts. Our study explored trends in family medicine clerkship design, length, and format and correlated these characteristics with high proportions of medical school graduates choosing family medicine.

Methods: We performed a secondary analysis of the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance annual family medicine clerkship director surveys from 2012 to 2023. We analyzed standard family medicine clerkship structure questions that were asked in each survey. We analyzed trends using Pearson’s correlation coefficient test and correlations with χ2 test for independence.

Results: Over the past 10 years, a transition from traditional block-style clerkships toward longitudinal-style clerkships has been increasing. Both block-style and longitudinal-style clerkships have decreased in length, with most clerkships lasting 4 weeks or less. A change also has taken place in the composition of clinical experiences, with reduced use of community preceptors as the primary source of clinical experiences. In 2021, schools with a higher percentage of students working with community preceptors were associated with higher percentages of medical students choosing to pursue family medicine.

Conclusions: Alterations in the family medicine clerkships have led to medical students getting decreased and intermittent exposure to family medicine. Most clerkship experiences are not with community preceptors, a major change following the COVID-19 pandemic. The repercussions of recent changes to the family medicine clerkship on the rate of matching medical students into family medicine remains unclear.

Family medicine clerkships traditionally occur during the third year of medical school, in a block format in which students are assigned a preceptor or clinic for a continuous period. Preceptors for these core clerkship rotations can be faculty members of the students’ medical school or community physicians who have agreed to teach and mentor students.

This traditional format, however, is now changing in some settings. Due to external factors that require an increased focus on clinical practice, community preceptors are becoming less likely to engage in teaching.1 Another recent change is the movement from a continuous block clerkship to longitudinal formats.2 A longitudinal clerkship may provide a longer experience with greater continuity of patient care, while a block clerkship may allow for a more intensive experience in family medicine.3

We describe the trends in family medicine clerkships over the past decade and correlate these characteristics with medical schools with higher percentages of graduates choosing family medicine.

Data were obtained from the publicly available data clearinghouse of the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA), whose surveys were approved by the American Board of Family Physicians’ Institutional Review Board prior to initial-administration. 4 CERA has conducted annual cross-sectional surveys of all allopathic and osteopathic family medicine clerkship directors from Canada and the United States. 5 These surveys began with standardized questions regarding the demographic data of the respondents and characteristics of the family medicine clerkship they oversaw. In those surveys, all family medicine clerkship directors received an email invitation to participate, followed by two email reminders before the survey closed. The data were made publicly available 90 days following the closing of each survey on the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine website.

Clerkship characteristic data in each survey from 2012 to 2023 were abstracted for trend line analysis (Appendix 1). Individual survey response rates ranged from 48.8% (in 2021 [78/160]) to 85.8% (in 2016 [121/141]). We analyzed clerkship design, clerkship length, completion year, use of regional campuses, use of community preceptors, need for overnight stays, and need to return to campus. We used descriptive statistics to describe trends in the data. Data were analyzed using R statistics software version R-4.2.2 (R Foundation). Trend line analysis was performed using linear logistic regression and Pearson’s correlation coefficient test.

We also incorporated the 2023 clerkship director survey question about institution location and the 2021 clerkship director survey question about the percentage of medical students matching into family medicine (a question added only to that specific survey) to examine the associations among clerkship, design, structure, and experiences to matching into family medicine. To evaluate these bivariate relationships, we used Pearson’s χ2 tests of independence, employing a level of statistical significance set at α=0.05.

Family Medicine Clerkship Design and Structure

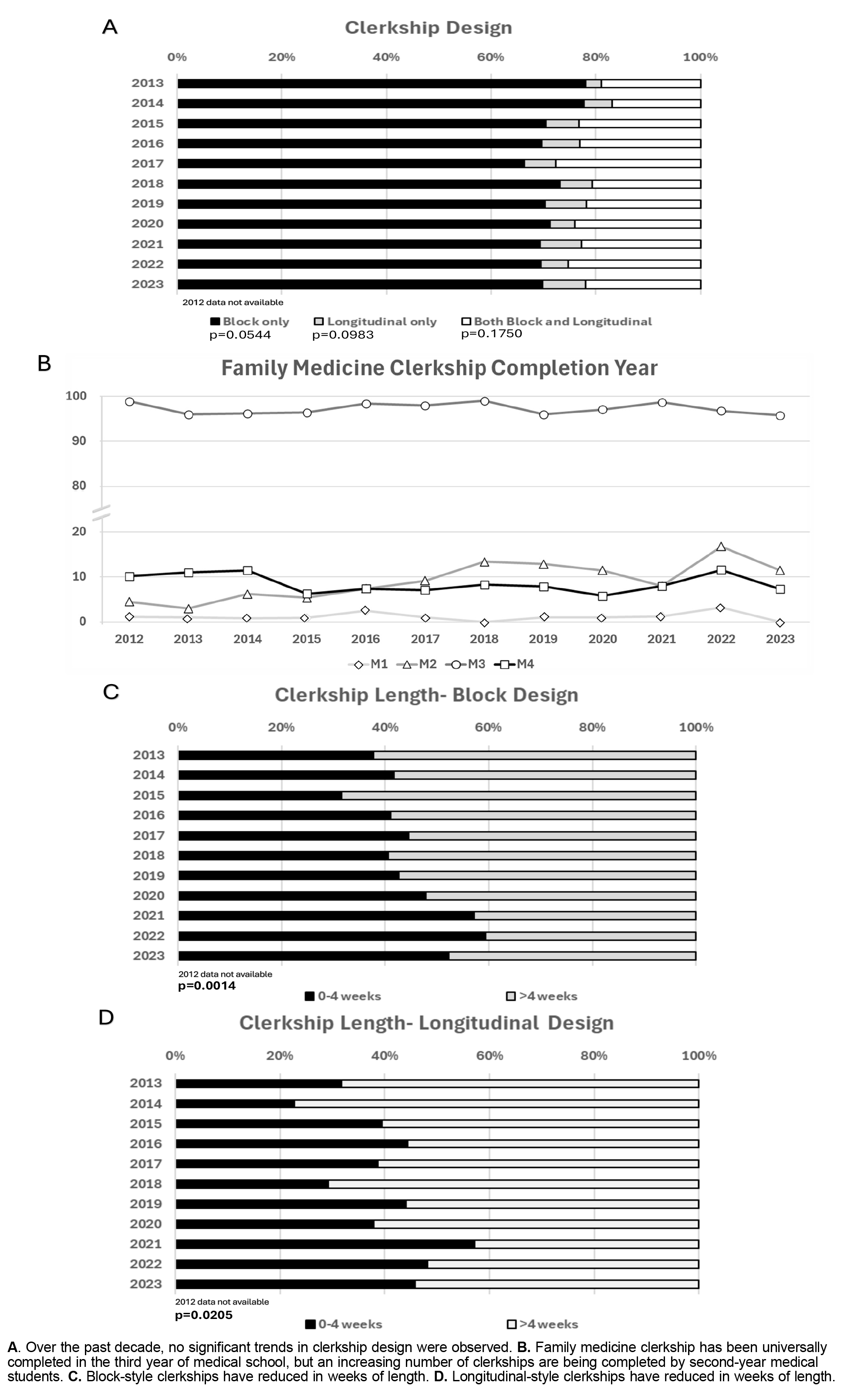

From 2012 to 2023, the family medicine clerkship was almost universally mandatory at the clerkship director’s institution (98%–100%). The family medicine clerkship format can be described as block design, longitudinal design, or a combination of the two.

This increase occurred from 2012 to 2017 and has since leveled off, with approximately 30% of family medicine clerkships having a longitudinal or combination design. Medical students almost always complete the family medicine clerkship during their third year of training (Figure 1B). The increase in numbers of longitudinal clerkships has led some institutions that were utilizing the fourth year for completion of training to shift to earlier during medical school, sometimes as early as the second year of training. In fact, 11.2% of respondents reported a family medicine clerkship occurring in the second year. Over the past decade, both the block and longitudinal clerkships have been reduced in total time (Figure 1 C Figure 1D). Block clerkships have reduced in length, with 37.7% being 4 weeks or less in 2012 to 52.2% being 4 weeks or less in 2023 (P=.0014). Likewise, from 2012 to 2023, the proportion of schools using longitudinal clerkships consisting of 4 weeks or less increased from 31.8% to 45.8% (P=.0205).

Regional Differences in the Family Medicine Clerkship Structure

Given the changes in clerkship design and length over the past decade, we next explored whether these characteristics had regional differences within the United States (Table 1). We used the data in 2023 (response rate 56.8% [96/169]) to analyze regional differences in family medicine clerkships. We found no significant differences in family medicine clerkship design, with equal proportions having either block design or some aspect of longitudinal design. We did find significant regional differences in clerkship length. These differences included East North Central (WI, MI, OH, IN, or IL) having a significantly higher proportion of clerkships of 4 weeks or less in length. In contrast, New England (NH, MA, ME, VT, RI, or CT) and Mountain (MT, ID, WY, NV, UT, AZ, CO, or NM) regions had significantly higher proportions of clerkships lasting more than 4 weeks in length (P=.012). We also analyzed differences between the United States and Canada in terms of structure of the family medicine clerkship. We found no statistically significant differences in clerkship design or clerkship length.

|

|

Clerkship design

|

Clerkship length

|

|

Block, n (%)

|

Longitudinal, n (%)

|

1–4 weeks, n (%)

|

>4 weeks, n (%)

|

|

Region

New England

Middle Atlantic

South Atlantic

East South Central

East North Central

West South Central

West North Central

Mountain

Pacific

Country

United States

Canada

|

3 (4.8)

12 (19.0)

13 (20.6)

2 (3.2)

12 (19.0)

6 (9.5)

6 (9.5)

4 (6.3)

5 (7.9)

63 (94.0)

4 (6.0)

|

4 (16.0)

3 (12.0)

4 (16.0)

0

5 (20.0)

2 (8.0)

2 (8.0)

3 (12.0)

2 (8.0)

(P=.067)

25 (86.2)

4 (13.8)

(P=.203)

|

0

8 (19.1)

7 (16.7)

1 (2.4)

11 (26.2)

6 (14.3)

3 (7.1)

1 (2.4)

5 (11.9)

42 (97.7)

1 (2.3)

|

6 (14.6)

6 (14.6)

9 (22.0)

1 (2.4)

5 (12.2)

2 (4.9)

5 (12.2)

5 (12.2)

2 (4.9)

(P =.012)

41 (87.2)

6 (12.8)

(P=.065)

|

Family Medicine Clerkship Experiences

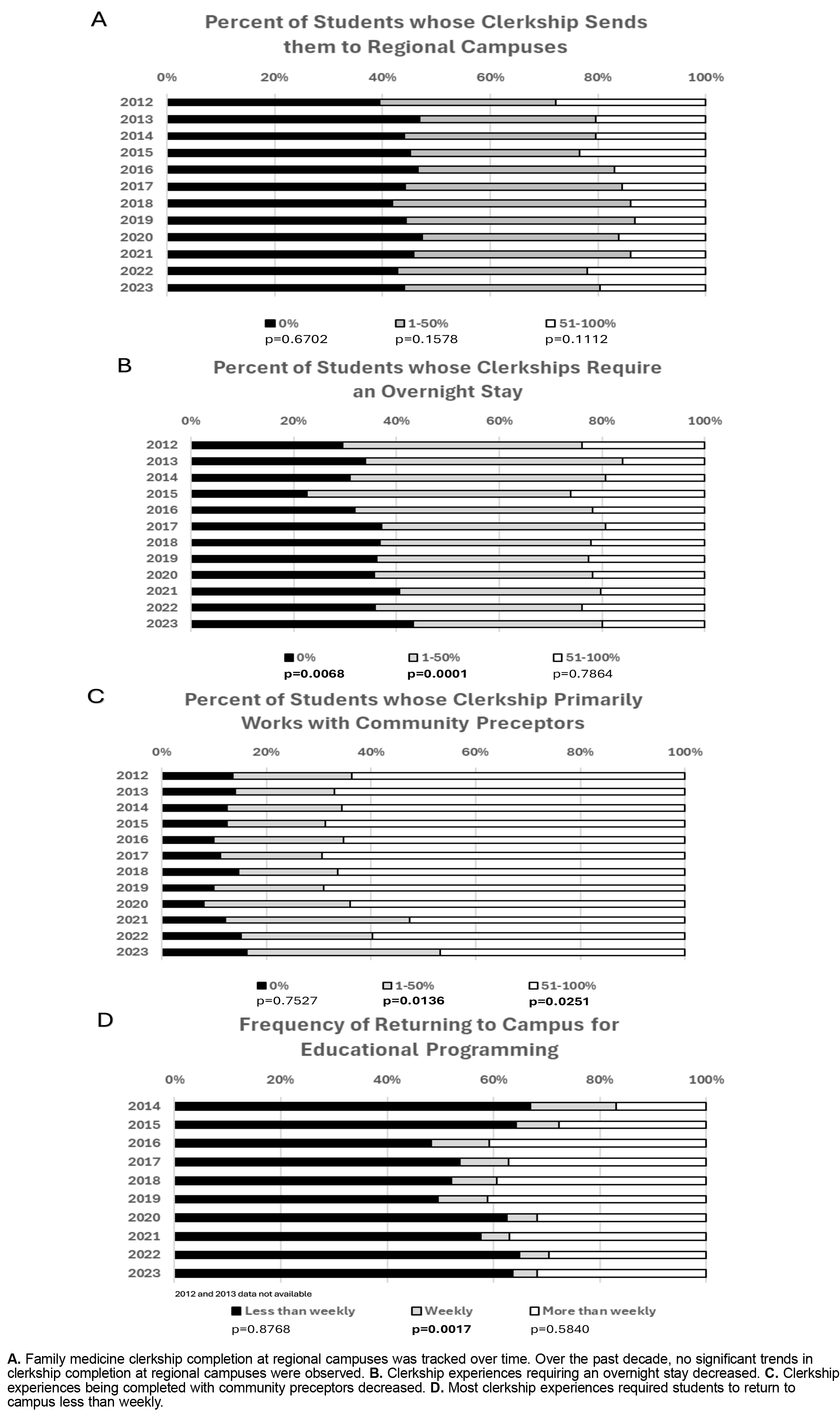

Family medicine clerkships can be completed at local institutions, regional campuses, or with community preceptors. Over the past decade, the proportion of students completing the clerkship at regional campuses has not changed (Figure 2A). Approximately 60% of medical students complete their clerkship at regional campuses. The proportion of students completing the family medicine clerkship with community preceptors has been decreasing since 2019 (Figure 2B). In 2012, 63.7% of clerkships had more than 50% of their medical students primarily with community preceptors. The proportion of clerkships with more than 50% of their medical students working primarily with community preceptors decreased to 46.8% in 2023 (P=.0251). The proportion of students needing to have overnight stays to complete their family medicine clerkship has decreased, indicating that more medical students are staying local for their learning (Figure 2C). In 2012, 70.5% of clerkships had some of their medical students requiring overnight stays, which decreased to 56.7% in 2023. Requiring students to return to campus more than weekly originally increased in frequency until 2019 before subsequently decreasing (Figure 2D). This U-shaped pattern correlates with the timing of the COVID-19 pandemic and the transition to virtual learning.

Family Medicine Clerkship Characteristics Associated With Matching Into Family Medicine

We next sought to identify characteristics of the family medicine clerkship that were associated with higher proportions of medical students matching into family medicine. We used data from 2021 (response rate 48.8% [78/160]) to analyze associations among clerkship design, clerkship length, and rotation with a community preceptor (Table 2). We found no association between clerkship design nor clerkship length and proportion of students matching into family medicine. Primary clerkship experiences with community preceptors were associated with more than 10% of medical students within an institution matching into family medicine (P<.0001).

|

|

Percentage of graduates pursuing family medicine, n (%)

|

χ2 value

|

P value

|

|

|

0%–10%

|

>10%

|

|

Family medicine clerkship design

Block only

Some longitudinal

|

.32 (42.7)

11 (14.7)

|

20 (26.7)

12 (16.0)

|

1.2

|

.268

|

|

Length of family medicine clerkship

1–4 weeks

>4 weeks

|

26 (35.1)

17 (23.0)

|

15 (20.3)

16 (21.6)

|

1.1

|

.302

|

|

Percentage of students working primarily with community preceptors

0%

1%–24%

25%–49%

50%–74%

75%–100%

|

7 (9.6)

9 (12.3)

8 (11.0)

8 (11.0)

10 (13.7)

|

2 (2.7)

5 (6.8)

4 (5.5)

3 (4.1)

17 (23.3)

|

37.7

|

<.0001

|

Family physicians are in short supply in the United States. As of November 20, 2023, approximately 102 million people lived in a primary care health professional shortage area; the goal of producing more family physicians is crucial to the success of our health care system. 6, 7 To provide for the health of our nation, US medical schools have a societal obligation to train competent physicians ready for indirect supervision of practice. Central to this tenet is ensuring that our medical education foundation is grounded in primary care and the development of this workforce is well-supported. Medical schools must promote family medicine as a discipline. Institutional support to pursue family medicine is important to students choosing family medicine as a specialty.8 Having access to quality, full-spectrum family medicine community preceptors during the family medicine clerkship positively influences students to choose primary care. 8

Our results revealed four main themes. First, an increasing number of family medicine clerkships have incorporated longitudinal design, and clerkship completion timing of medical students is shifting from the fourth year of training to earlier during the second year of training. Second, more programs are reducing the length of their clerkships to 4 weeks or less. Third, the quantity of students completing third year clerkships with community preceptors and/or away from their home medical schools has decreased. Finally, in the 2021 survey data, clerkships with more than 75% use of primary experiences with community preceptors were associated with more than 10% of medical students within an institution matching into family medicine. We recognize thata medical students’ specialty choice is a complex decision, and COVID-19 pandemic-related restrictions may have impacted medical student engagement with community preceptors. Our data suggest that primary use of community preceptors during the family medicine clerkship is associated with students choosing primary care, but additional longitudinal data to reinforce this observation is needed.

Our data were limited by the family medicine clerkship directors who were surveyed and completed the survey. Previous methodology manuscripts have shown that the clerkship director survey does not have significant differences between respondents and nonresponders in terms of demographic data.5 Other limitations of our study included use of survey data that were not originally deployed for the objectives we sought to answer in this study. Additionally, one survey in 2021 had a response rate that was less than 50% of clerkship directors; overall, the response rate has declined over time. Finally, the use of the term “community preceptor” could be interpreted differently by survey respondents due to newer Liaison Committee on Medical Education requirements that all medical student preceptors have a faculty appointment at their college of medicine. Because of this change, respondent confusion in the use of the term may have impacted the survey results.

More medical schools are shifting family medicine clerkship format and length, but these changes were not associated with the choice to pursue family medicine. Family medicine clerkship experiences that occurred primarily with community preceptors was the only characteristic associated with the choice to pursue family medicine. The decline in access to community preceptors over the last 10 years may portend recruitment challenges for our specialty. Further studies are needed to assess why students have less access to community preceptors. One explanation may be that community preceptors are experiencing financial pressures from the lack of support from health systems. The proportion of community-based practitioners is declining as more family physicians entering practice are now employed. A review of current American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) data revealed that only 9% of physicians are self-employed.9 Similarly, community preceptors who enjoyed teaching may be transitioning their practice to fill shortages in academic positions. Our data showed that the large reductions in primary experiences with community preceptors occurred following the COVID-19 pandemic. During that time, community preceptors possibly paused acceptance of medical students and never restarted.

Preceptor shortages have been a reality at many institutions, and creative solutions are being sought. 10, 11 Continuing to educate community preceptors on the benefits of working with medical students, such as the reduction of burnout, personal fulfilment, and not significantly impacting productivity, is important.12 AAFP continues to advocate for increased time within family medicine core clerkship experiences to increase the number of students choosing family medicine as a specialty. Specifically, AAFP has called for a required third-year clerkship, a required fourth-year clerkship, elective rotation options, accelerated tracks, and longitudinal programs that together allow students to experience continuity of care.11 Despite these calls, medical schools have not made family medicine clerkship decisions in alignment with these goals. The current evolution of the family medicine clerkship could significantly harm the future of the family medicine workforce if current trends continue.

Over the past decade, the family medicine core clerkship has changed in structure, length, and experiences. Family medicine clerkship experiences with community preceptors are associated with a greater percentage of a medical school’s graduates matching into a family medicine residency program. The changes to the family medicine clerkship may decrease the proportion of medical students choosing family medicine as a career. Exploring incentives to encourage community preceptors’ participation in teaching clerkship students may be critical to maintaining the US family medicine workforce.

Acknowledgment

These data were collected as part of multiple surveys conducted by the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA). These projects were approved by the American Academy of Family Physician’s Institutional Review Board.

Presentations

Ringwald B, Banas D, Bruce E, Farrell M, Macerollo A. Evolution of the Family Medicine Clerkship: A CERA Secondary Analysis. Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Conference for Medical Student Education, January 30–February 2, 2025, San Antonio, TX.

References

-

Minor S, Huffman M, Lewis PR, Kost A, Prunuske J. Community preceptor perspectives on recruitment and retention: the CoPPRR study.

Fam Med. 2019;51(5):389-398.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.937544

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Longitudinal integrated clerkships at US medical schools. Accessed October 16, 2024. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/curriculum-reports/data/longitudinal-integrated-clerkships-us-medical-schools

-

Lee AL, Erlich DR, Wendling AL, et al. The relationship between medical school clerkships and primary care specialty choice: a narrative review.

Fam Med. 2022;54(7):564-571.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2022.857719

-

Seehusen DA, Mainous AG III, Chessman AW. Creating a centralized infrastructure to facilitate medical education research.

Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):257-260.

doi:10.1370/afm.2228

-

-

-

-

Alavi M, Ho T, Stisher C, et al. Factors that influence student choice in family medicine: a national focus group.

Fam Med. 2019;51(2):143-148.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.927833

-

-

Robinson SK, Meisnere M, McCauley L, Phillips RL Jr, et al, eds; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee on Implementing High-Quality Primary Care. Implementing High-Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care. National Academies Press; 2021.

-

-

Sairenji T, Griffin S, Keen M. The effect of teaching family medicine clerkship students on preceptor productivity.

PRiMER. 2020;4:8.

doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2020.550339

There are no comments for this article.