The current political and social climate is directly and indirectly impacting the work-life wellness of family medicine faculty who are underrepresented in medicine (URiM). Furthermore, issues of social justice are an intimate part of the lived experience of URiM faculty physicians and cannot be ignored. Institutional programs and offices that have traditionally served to support URiM faculty—namely diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) offices and programs—are actively being dismantled through anti-DEI legislation across the country. Where do such changes leave URiM faculty in terms of career advancement and support? Studies show that mentorship is necessary and effective in URiM faculty development. Despite the gains through mentorship, gaps in the support of URiM faculty are obstacles to their reaching their highest potential. Obstacles such as pseudoleadership, scholarship delay, minority taxation, and income inequality make succeeding at their institution more difficult for these faculty members. These hurdles confound the reality that URiM faculty physicians tend to have value systems surrounding their own self-actualization, family structure, and professional development that differ from institutional priorities. Lack of awareness of these differences in mentorship needs has negative consequences for the growth and advancement of both URiM faculty and their institutions. Prioritization of effective mentorship strategies is necessary to bridge the value differences and overcome the obstacles that will ultimately benefit both the institutions and their URiM faculty. This article defines the gaps in mentorship of URiM faculty, introduces strategies for closing the mentorship gaps, and summarizes how doing so produces gains on a systemic level.

As has been well established, URiM faculty need specialized mentorship in academic medicine. 1-4 For the purposes of this manuscript, we refer to URiM faculty as those who identify as Black or African American, Latinx (Hispanic or Latino), American Indian and Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, and Southeast Asian. Addressing cultural diversity is important and necessary in mentoring and creating successful mentoring relationships, 5, 6 particularly those that are cross-cultural or across different ethnic backgrounds of mentors and mentees. In a cross-sectional study evaluating mentorship practices in military family physicians, where only 10% of the study participants identified as URiM, approximately half of the respondents had not mentored a URiM faculty member in a scholarship project within the past 3 years or were not able to recognize and confidently address the minority tax, racism, and isolation that URiM faculty commonly face. 6 The minority tax, a key deterrent to actualizing academic advancement, is defined as the extra burden of roles and responsibilities disproportionately assigned to URiM faculty solely because of their ability to fulfill minority representation goals or mandates. 7-9

Despite the mounting evidence of the importance of mentorship in attaining academic success of URiM faculty physicians, a dearth of literature names the gaps in mentorship that URiM family physicians face and addresses how to fill these gaps in a culturally competent manner. Many of the published studies focus on elements of effective mentorship and strategies for implementation, such as structured and tailored faculty development, fellowships, and optimal models of mentorship. The cross-sectional mentorship study previously cited appears to be the only study to date that begins to define the problems surrounding mentoring URiM family medicine faculty, which include lack of URiM mentors, the burdens of the minority tax, and the inexperience of non-URiM faculty in addressing these issues.

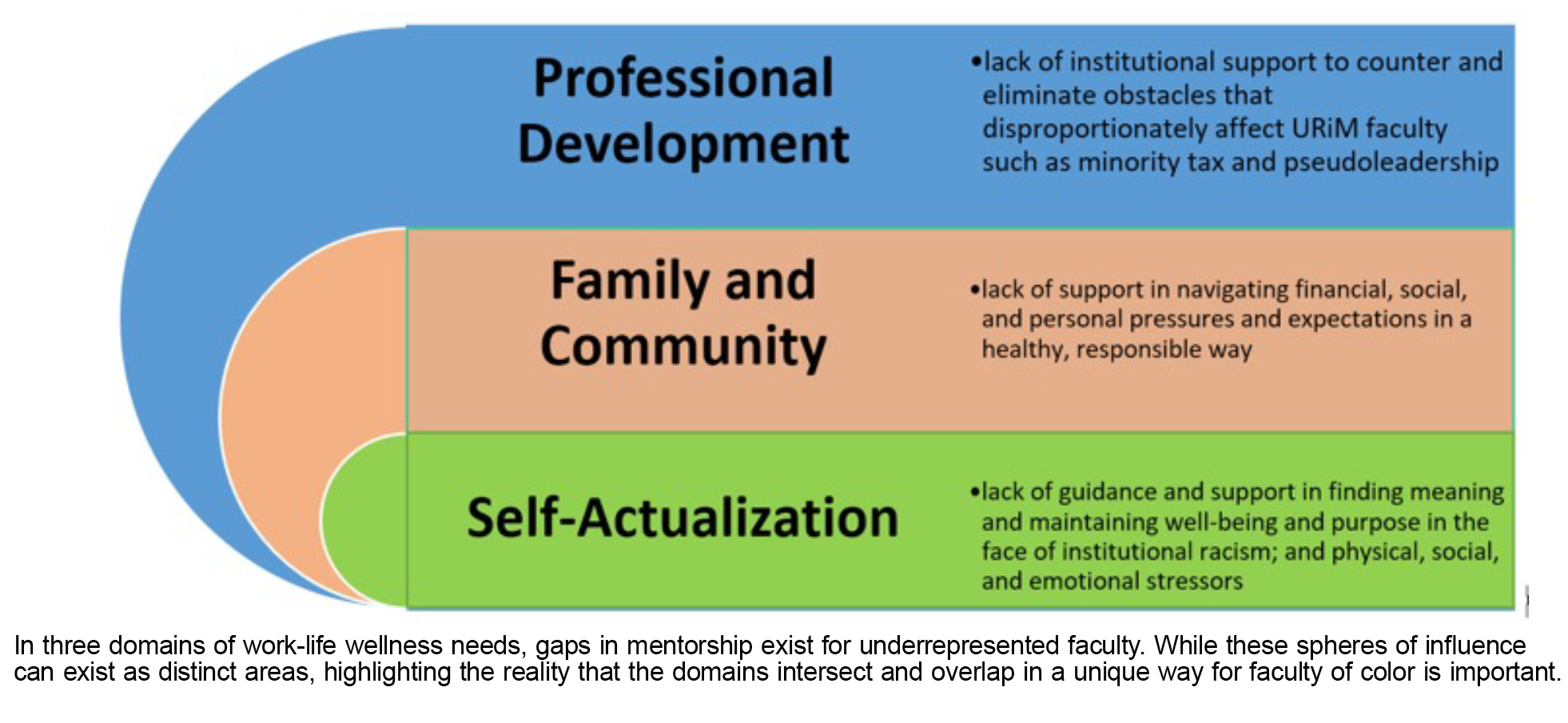

Despite some advances, gaps in mentorship remain that have yet to be addressed in family medicine faculty who are URiM. These gaps include mentorship for issues that occur mostly outside of the realms of education, clinical care, and research but that have direct impacts on faculty growth and success. Family medicine has proven to be a leader in developing URiM faculty, with the most diverse department chairs of any specialty and programing to promote the success of underrepresented faculty groups. 10-12 Because of our diversity gains and the comprehensive and detailed approach to our work, 13 academic family physicians are natural leaders to address mentorship gaps. While work exists on addressing mentorship surrounding work-life balance in the broader academic health care professions such as psychiatry, surgery and nursing, 14-18 comparable literature on such topics focused on underrepresented minorities in academic family medicine does not seem to exist to date. In this article, we aim to define three key gaps in mentorship that occur for underrepresented faculty in promoting work-life wellness. In addition, we provide a table of action items to address these barriers and promote effective and impactful mentorship. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to describe what is missing in mentorship of URiM faculty and to identify a systemic approach to close these gaps (Figure 1).

Gap 1: Mentorship for Self-Actualization

The mentorship gap in self-actualization relates to supporting URiM faculty in pursuing their ideals in their work and can be subdivided into various domains such as physical, mental, spiritual, and financial. 19 Mentorship on how to address these personal wellness domains includes building in time for personal fitness and mental wellness activities along with centering spirituality and financial security in a busy work schedule. Lack of guidance on how to address faith and spirituality make addressing work life well-being and professional growth difficult for any faculty member. 20, 21 The medical community is increasingly recognizing the importance of mentoring for well-being in general. The surgical department at Massachusetts General Hospital used a model of combining mentoring with wellness coaching for early career faculty members, who in turn found the program beneficial and desired to pursue further wellness coaching. 22 While the role of spirituality impacting wellness is acknowledged, the specifics of how to support physicians regarding their spirituality is lacking in the literature. 20 Whenever a faculty member finds their practice and institutional values in conflict with their faith-based practices, challenges may arise that can create dissonance and isolation, and contribute to burnout. 23

Initiatives to promote faculty wellness address some of these gaps globally but are geared to respond to the direct stressors brought about by pajama time 24 to address patient messages, respond to labs, and complete clinic notes after the clinic day has ended, as well as meet other administrative demands linked to patient care. 25 Inequities for underrepresented faculty, such as acquiring more personal and family debt than well-represented colleagues 26 and experiencing the generational wealth gap, 27 do not just exist in the work environment; therefore, mentorship in these areas is critical to this group’s success on a daily basis. 26, 28 Financial well-being plays a critical role in self-actualization for URiM faculty. With the known income disparities among physicians of color compared to their white counterparts, 29 not surprisingly, this group may grapple more with financial challenges, including managing higher medical school debt and new income while struggling to combat the chronic and pervasive burdens of generational poverty. 30 A scenario that exemplifies this situation is a URiM early career faculty who was awarded a small institutional grant for an endeavor with a reimbursement of funds requirement. The expectation of the institution is that this faculty member has the personal finances or credit to assume the responsibility of funding the needs of their project with the space and time to await reimbursement. The financial burden this situation unconsciously places on the URiM faculty poses a threat to executing the grant-related tasks in a timely fashion and may hinder their professional advancement down the line.

Lack of mentorship in how to manage personal income, including income security and growth, generational wealth building, and investment strategies, inevitably leads to significant imbalances in work-life wellness that can impact health outcomes. 26 With the rising hostile political environment geared at banning diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives in US academic institutions, these imbalances in juggling career demands and prioritizing well-being likely will be magnified. Downstream effects will inevitably threaten productivity, career growth, and retention of URiM faculty. Mentorship can help change this narrative if mentors can provide guidance on available resources, goal setting, and accountability around navigating financial well-being as central components of development for URiM faculty. Furthermore, as supported in the literature, mentors who can incorporate the principles of logotherapy into how they engage mentees can facilitate mentees finding meaning and purpose in their current situations and making decisions from a place of choice rather than feeling forced or pressured. 31, 32

Gap 2: Mentorship for Family and Community Responsibilities

The second mentorship gap relates to issues that impact caring for family and managing community responsibilities, including pressures and expectations, for URiM family medicine faculty. Castaneda et al discussed the diverse definitions of family within the community, which encompass variations in race, ethnicity, spirituality, and life stages. 33 Underrepresented minority faculty may find themselves accountable not just for their own children and aging parents but also for other relatives, friends, and even members of their community. 34, 35

Meeting these demands can be complex when families are large and family support needs are expansive and include financial and other supports that extend beyond their immediate household. Simple everyday tasks such as family meal preparation, childcare/parenting demands, housekeeping, home maintenance needs, and transportation demands become complicated when accounting for all who depend on a person. Family health navigation plays a role as well, dealing with health insurance coverage, managing copays, and finding time to meet health care needs, including those of extended family like grandparents or children who may have special needs. 18 URiM faculty, who are often first-generation physicians, are perceived by their family members as financially stable and thus are expected to carry the financial burden of their family. This caring for family can leak over into their community, moving from the personal family to the community family. Studies have shown that underrepresented faculty frequently serve vulnerable patient populations, 36 which may result in longer clinic hours that further encroach upon family and community responsibilities, making fulfilling parental duties like attending after-school events and parent-teacher conferences more difficult. 37, 38

Underrepresented minority faculty may experience heightened pressures related to childcare responsibilities and the need to balance personal commitments with career advancement. They may hesitate to utilize institutional work-family policies, fearing potential negative repercussions on their tenure or career progression. Furthermore, women often bear the weight of childcare and household responsibilities within the family, known as the “child tax” exacerbating the struggle for work-life balance, 39 This tax highlights the disproportionate burden placed on women in caring for dependents compared to their male counterparts. These challenges can impede the career advancement of women faculty, exemplified by the finding that those with young children are 28% less likely to secure tenure-track positions, thus adding more pressure on underrepresented female faculty. 39 Duties of service to the family and community all play into the minority tax as well as pseudoleadership and the scholarship delay.

Mentors can try to minimize meetings outside of business hours. 40 They also can provide a space for URiM faculty to explore old and new norms of work-life balance by sharing their own approach as well as other approaches that faculty members have utilized. Furthermore, mentors can raise the gaps or challenges within their institution to explore system-based solutions. Institutional efforts can help offset these challenges to improve the retention of underrepresented minority faculty; however, the recent threat to institutional DEI initiatives may jeopardize efforts geared toward addressing barriers that disproportionately affect underrepresented minority faculty.

Gap 3: Mentorship for Professional Development

In light of legislation to dismantle and defund DEI programming, 41-43 and the Embracing Anti-Discrimination, Unbiased Curricula, and Advancing Truth in Education (EDUCATE) Act banning race-based mandates that promote DEI at medical schools and their accrediting bodies, 44, 45 having effective mentors and mentoring relationships is now more important than ever for underrepresented faculty. Sixty-six percent of chairs of family medicine departments across the country stated that they felt their institution had infrastructure for diversity and inclusion that was working well, and approximately 45% had a diversity/inclusion officer as part of that infrastructure. 46 The emerging federal mandates effectively banning DEI efforts across the nation create yet another challenge in promoting equitable environments where URiM faculty can thrive.

The disparity in clinical professors of color 47 is because of the systemic challenges that URiM academic physicians are navigating and having to overcome. Systemic solutions are necessary to address systemic challenges. One systemic solution was institutions recognizing the value of DEI roles and efforts and allowing URiM contributions in this area to be utilized for their academic promotion. 46 However, because of the current legislative ban on DEI efforts in certain states, institutions are having to work with URiM faculty to determine a new plan for how their time and work is valued and promoted. In addition, institutions must rethink how they will address the challenges in scaling effective efforts to have a larger impact on addressing their institutional challenges that predominately impact URiM faculty. Underrepresented faculty are more likely to mentor faculty from similar cultures and diverse backgrounds and are well-equipped to address issues such as institutional racism and the minority tax that undoubtedly threaten their academic appointment and advancement. 48 Thus, with few clinical professors of color, early and mid-career URiM faculty may have more challenges in finding a mentor, with limited protected time to learn how to navigate their institution’s specific culture and the minority tax. Moreover, URiM faculty serving as mentors will be further taxed with the burden of balancing increased institutional workload with their own personal well-being and responsibilities. The legislative removal of DEI programs and roles will inevitably propagate the mentorship gap.

Mentorship on how to avoid being made a pseudoleader in the academic medical environment is also needed. Pseudoleadership occurs when faculty are placed in leadership roles due to their identities without being provided the support, training, resources, and institutional preparation and equity to excel in the leadership role. 8, 49 Only half of the departments with a diversity officer stated that the role had a pathway for promotion and career advancement in their department or institution, and only half of those departments with career advancement opportunities provided their diversity officer with protected time and resources to perform the duties of the role. 46 This reality creates a challenge in maintaining work-life wellness and poses a threat to professional growth and success in several ways. If someone is promoted to a role without the proper training and resources, they have a lower likelihood of achieving success in the leadership role, recognizing their own weaknesses, or mentoring someone else effectively for the role. Moreover, other junior faculty may be discouraged from pursuing leadership due to the observed physical, emotional, and personal toll their colleagues experienced.

We encourage mentors to develop awareness of nationally funded programs, such as the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Leadership Through Scholarship Fellowship, that have already built in protected time, reducing the burden on the scholar to advocate and fund time away from clinical duties. 50, 51 Programs such as these not only provide targeted faculty development for URiM faculty, but also provide a safe space to explore old and new norms of work-life balance, while hearing firsthand experience of how senior faculty mentors navigated the inevitable challenges that arise. Furthermore, a group can troubleshoot the discovery of gaps or challenges within these protected settings, while simultaneously mitigating the mentee’s fear of retaliation at their home institution.

This manuscript serves as a call to action to share recommendations on how to address the three gaps that we have defined that impact the recruitment, retention, advancement, and wellness of faculty underrepresented in medicine. Mentors and mentees remain subject to navigating institutional barriers; therefore, stakeholders must be involved in creating a system that facilitates mentors and mentees working together to close the gaps identified. For example, Johns Hopkins University made an institutional commitment to implement various gender equity initiatives, which resulted in a reduction in the salary gap and time to promotion for all faculty. In Table 1 , we identify the mentorship gap, key stakeholders who should close the gap, and specific actions that have been recommended or should be explored to close the gap.

|

Mentorship gap

|

Key stakeholders

|

Actions

|

|

Self-actualization

|

- Human Resources

- Faculty Affairs and Development

- Deans and health system leaders

- Extramural and national organizations

|

- Provide ongoing funding for outside behavioral health professionals to provide faculty mentorship, training in cultural humility, and support for racially or ethnically concordant clinicians. 18

- Pay for and provide gym membership and personal trainers for all interested faculty.

- Fund cultural and spiritual wellness spaces for faculty along with a spiritual mentor or chaplain for faculty support beyond hospital- or patient-focused services.

- Promote salary equity as essential to the mission of the institution and have a continued review process for faculty salary analyses, with leadership directing actions toward departments with salary disparities to narrow the gap. 40

- Dedicate financial resources such as a financial advisor for financial planning, mentorship, and wealth building advice beyond that of retirement planning. 18, 40

- Integrate a culture of promoting well-being by providing opt-out opportunities to financially support URiM faculty time in accessing national conferences, career coaches, and extramural resources focused on cultivating wellness and self-care. 52

|

|

Family and community responsibilities

|

- Human Resources

- Faculty Affairs and Development

|

- Pay for and provide a personal mentor to provide mentorship on how to access flexible work hours and when to use special leave. Further develop, fund, and expand employer-sponsored childcare programs. 53

- Pay for and provide a home care mentor who will give advice on meeting meal preparation needs for a busy family, childcare and parenting demands, housekeeping and home maintenance needs, and transportation demands such as car repairs.

- Include mentorship on how to align and stack clinical and academic responsibilities so that time is created or reserved to address health care needs that arise for family and extended family. 54

- Form faculty-focused resource groups that can speak to cultural and background differences of families and provide standardized expectations of activity engagement and the protected nonclinical time necessary to effectively engage in those activities. 55-57

|

|

Professional development

|

- Faculty Affairs and Development

- Extramural and national organizations

- Office of Graduate Medical Education

- Department chairs, deans, and health system leaders

|

- Ensure equitable experiences for those who are underrepresented and make sure that they receive necessary support for advancement and career success through institutional and national programs. 50, 51

- Provide resources and assume responsibility for faculty success and advancement, including making sure that underrepresented faculty have access to needed resources and equitable experiences for promotion.

- Require them to know the literature regarding how to promote the success of underrepresented faculty. 18, 58, 59

|

In this article, we have defined and provided recommendations to address three mentorship gaps perceived for faculty who are underrepresented in medicine: mentorship for self-care and well-being, mentorship for family and community responsibilities, and mentorship for thriving in environments that are hostile to DEI efforts and do not provide an equitable environment for promotion and tenure. While paying for the actions recommended in this manuscript may seem challenging given tight budgets, we believe these to be investments in faculty that will not only promote faculty wellness but also increase faculty retention and productivity. resulting in enhancements to the education, research, and clinical care missions of our academic health centers. Funding for these actions could be from clinical revenues, endowments or foundation accounts, or state budgets that value the importance of such actions. It’s time for radical thinking, exploring new paths, and working in different ways to promote the retention, advancement, and career success of faculty who are underrepresented in medicine.

References

-

Fishman J. Mentorship in academic medicine: competitive advantage while reducing burnout?

Health Sci Rev (Oxf). 2021;1:100004.

doi:10.1016/j.hsr.2021.100004

-

Bhatnagar V, Diaz S, Bucur PA. The need for more mentorship in medical school.

Cureus. 2020;12(5):e7984.

doi:10.7759/cureus.7984

-

Fraser K, Dennis SN, Kim C, et al. Designing effective mentorship for underrepresented faculty in academic medicine.

Fam Med. 2024;56(1):42-46.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2023.186051

-

Bonifacino E, Ufomata EO, Farkas AH, Turner R, Corbelli JA. Mentorship of underrepresented physicians and trainees in academic medicine: a systematic review.

J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(4):1,023-1,034.

doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06478-7

-

Byars-Winston A, Butz AR. Measuring research mentors’ cultural diversity awareness for race/ethnicity in STEM: validity evidence for a new scale.

CBE Life Sci Educ. 2021;20(2):ar15.

doi:10.1187/cbe.19-06-0127

-

Harris LM, Pierre EF, Almaroof N, Cimino FM. Cross-cultural mentorship in military family medicine: defining the problem.

Fam Med. 2023;55(9):607-611.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2023.794972

-

Robles J, Anim T, Wusu MH, et al. An approach to faculty development for underrepresented minorities in medicine.

South Med J. 2021;114(9):579-582.

doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000001290

-

Amaechi O, Foster KE, Tumin D, Campbell KM. Addressing the gate blocking of minority faculty.

J Natl Med Assoc. 2021;113(5):517-521.

doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2021.04.002

-

Alhassan AI. Implementing faculty development programs in medical education utilizing Kirkpatrick’s model.

Adv Med Educ Pract. 2022;13:945-954.

doi:10.2147/AMEP.S372652

-

Meadows AM, Skinner MM, Hazime AA, Day RG, Fore JA, Day CS. Racial, ethnic, and sex diversity in academic medical leadership.

JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(9):e2335529.

doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.35529

-

Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Rayburn WF. Diversity of department chairs in family medicine at US medical schools.

J Am Board Fam Med. 2022;35(1):152-157.

doi:10.3122/jabfm.2022.01.210298

-

Stubbs B, Krueger P, White D, Meaney C, Kwong J, Antao V. Mentorship perceptions and experiences among academic family medicine faculty: findings from a quantitative, comprehensive work-life and leadership survey. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(9):e531-e539.

-

Theobald M. STFM launches initiative to position academic family medicine in health systems.

Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(5):470-471.

doi:10.1370/afm.2595

-

-

Alegría M, Fukuda M, Lapatin Markle S, NeMoyer A. Mentoring future researchers: advice and considerations.

Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2019;89(3):329-336.

doi:10.1037/ort0000416

-

Crawford RP, Barbé T, Troyan PJ. A national qualitative study of work-life balance in prelicensure nursing faculty.

Nurs Educ Perspect. 2023;44(1):30-35.

doi:10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000001046

-

Greenberg N, Lawrence E, Myers O, Sood A. Factors related to faculty work life balance as a reason to leave a school of medicine. Chron Mentor Coach. 2021;5(14):353-359.

-

Kalet A, Libby AM, Jagsi R, et al. Mentoring underrepresented minority physician-scientists to success.

Acad Med. 2022;97(4):497-502.

doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004402

-

Del Castillo FA. Self-actualization towards positive well-being: combating despair during the COVID-19 pandemic.

J Public Health (Oxf). 2021;43(4):e757-e758.

doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdab148

-

Liu CJ, Pi SH, Fang CK, Wu TY. Development and evaluation of psychometric properties regarding the whole person health scale for employees of hospital to emphasize the importance of health awareness of the workers in the hospital.

Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(5):610.

doi:10.3390/healthcare9050610

-

Fang CK, Li PY, Lai ML, Lin MH, Bridge DT, Chen HW. Establishing a ‘physician’s spiritual well-being scale’ and testing its reliability and validity.

J Med Ethics. 2011;37(1):6-12.

doi:10.1136/jme.2010.037200

-

Frates B, Cron D, Lubitz CC, et al. Incorporating well-being into mentorship meetings: a case demonstration at Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Surgery a Harvard Medical School affiliate.

Am J Lifestyle Med. 2022;17(2):213-215.

doi:10.1177/15598276221105830

-

Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Thanh NX, Jacobs P. How does burnout affect physician productivity? a systematic literature review.

BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):325.

doi:10.1186/1472-6963-14-325

-

Rotenstein LS, Holmgren AJ, Horn DM, et al. System-level factors and time spent on electronic health records by primary care physicians.

JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(11):e2344713.

doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.44713

-

Saag HS, Shah K, Jones SA, Testa PA, Horwitz LI. Pajama time: working after work in the electronic health record.

J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(9):1,695-1,696.

doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05055-x

-

Hamil-Luker J, O’Rand AM. Black/White differences in the relationship between debt and risk of heart attack across cohorts.

SSM Popul Health. 2023;22:101373.

doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2023.101373

-

Pfeffer FT, Killewald A. Generations of advantage. multigenerational correlations in family wealth.

Soc Forces. 2018;96(4):1,411-1,442.

doi:10.1093/sf/sox086

-

Phillips J. The impact of debt on young family physicians: unanswered questions with critical implications.

J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(2):177-179.

doi:10.3122/jabfm.2016.02.160034

-

Sanders K, Phillips J, Fleischer S, Peterson LE. Early-career compensation trends among family physicians.

J Am Board Fam Med. 2023;36(5):851-863.

doi:10.3122/jabfm.2023.230039R1

-

Dugger RA, El-Sayed AM, Dogra A, Messina C, Bronson R, Galea S. The color of debt: racial disparities in anticipated medical student debt in the United States.

PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74693.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0074693

-

Riethof N, Bob P. Burnout syndrome and logotherapy: logotherapy as useful conceptual framework for explanation and prevention of burnout.

Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:382.

doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00382

-

Sheykhi M, Naderifar M, Firouzkohi M, Abdollahimohammad A. Effect of group logotherapy on death anxiety and occupational burnout of special wards nurses. Med Sci. 2019;23:532-539.

-

Castañeda M, Zambrana R, Marsh K, Vega W, Becerra R, Pérez D. Role of institutional climate on underrepresented faculty perceptions and decision making in use of work–family policies.

Fam Relat. 2015;64(5):711-725.

doi:10.1111/fare.12159

-

Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Woodward AT, Brown E. Racial and ethnic differences in extended family, friendship, fictive kin and congregational informal support networks.

Fam Relat. 2013;62(4):609-624.

doi:10.1111/fare.12030

-

Nguyen AW, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ. African American extended family and church-based social network typologies.

Fam Relat. 2016;65(5):701-715.

doi:10.1111/fare.12218

-

Jetty A, Hyppolite J, Eden AR, Taylor MK, Jabbarpour Y. Underrepresented minority family physicians more likely to care for vulnerable populations.

J Am Board Fam Med. 2022;35(2):223-224.

doi:10.3122/jabfm.2022.02.210280

-

Brown JB, Reichert SM, Boeckxstaens P, Stewart M, Fortin M. Responding to vulnerable patients with multimorbidity: an interprofessional team approach.

BMC Prim Care. 2022;23(1):62.

doi:10.1186/s12875-022-01670-6

-

DePuccio M, McClelland L, Vogus T, Mittler J, Singer S. Team strategies to manage vulnerable patients’ complex health and social needs: considerations for implementing team-based primary care. J Hosp Management Health Policy. 2021;5:2,523-2,533.

-

Cardel MI, Dhurandhar E, Yarar-Fisher C, et al. Turning chutes into ladders for women faculty: a review and roadmap for equity in academia.

J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2020;29(5):721-733.

doi:10.1089/jwh.2019.8027

-

Rao AD, Nicholas SE, Kachniarz B, et al. Association of a simulated institutional gender equity initiative with gender-based disparities in medical school faculty salaries and promotions.

JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(8):e186054.

doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6054

-

Karra L, Johnson M, Piggott C. Defunding of diversity and inclusion programs in undergraduate and graduate medical education.

PRiMER. 2020;4:11.

doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2020.971896

-

Diaz J. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signs a bill banning DEI initiatives in public colleges. NPR. May 15, 2023.

-

-

-

-

Jacobs CK, Douglas M, Ravenna P, et al. Diversity, inclusion, and health equity in academic family medicine.

Fam Med. 2022;54(4):259-263.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2022.419971

-

Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Pololi LH. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax?

BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):6.

doi:10.1186/s12909-015-0290-9

-

Hassouneh D, Lutz KF, Beckett AK, Junkins EP Jr, Horton LL. The experiences of underrepresented minority faculty in schools of medicine.

Med Educ Online. 2014;19(1):24768.

doi:10.3402/meo.v19.24768

-

Santiago-Delgado Z, Rojas DP, Campbell KM. Pseudoleadership as a contributor to the URM faculty experience. J Natl Med Assoc. 2023;115(1):73-76.

-

-

Nolte T. STFM launches interprofessional leading change fellowship.

Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(6):593.

doi:10.1370/afm.1879

-

Sevelius JM, Harris OO, Bowleg L. Intersectional mentorship in academic medicine: a conceptual review.

Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024;21(4):503.

doi:10.3390/ijerph21040503

-

-

Durbin DR, House SC, Meagher EA, Rogers JG. The role of mentors in addressing issues of work-life integration in an academic research environment.

J Clin Transl Sci. 2019;3(6):302-307.

doi:10.1017/cts.2019.408

-

Bartlett MJ, Arslan FN, Bankston A, Sarabipour S. Ten simple rules to improve academic work-life balance.

PLOS Comput Biol. 2021;17(7):e1009124.

doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009124

-

Griesbach S, Theobald M, Kolman K, et al. Joint guidelines for protected nonclinical time for faculty in family medicine residency programs.

Fam Med. 2021;53(6):443-452.

doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.506206

-

-

-

Keating JA, Jasper A, Musuuza J, Templeton K, Safdar N. Supporting midcareer women faculty in academic medicine through mentorship and sponsorship.

J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2022;42(3):197-203.

doi:10.1097/CEH.0000000000000419

There are no comments for this article.