Background and Objectives: Family medicine residency training emphasizes the importance of community medicine. Recent scholarship has helped to identify important elements of community partnerships, including bidirectionality and continuity. Given the importance of continuity in family medicine and community partnerships, this study explores the relationship between continuity in community medicine curricula, partnership quality, and residents’ community medicine competency.

Methods: Survey questions were included in the 2015-2016 Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) Family Medicine Program Director survey that probed community medicine curricular structures, partnership quality, and outgoing resident competency in community medicine. Multivariate logistic regression was used to test the impact of continuity on the outcomes of partnership quality and residents’ community medicine competency.

Results: Respondents represented 227 of 461 family medicine programs (49%). Block rotation, used in 150 (66%) programs, was the approach most commonly used to deliver community medicine curriculum. Eighty-five (45%) programs self-reported high quality partnerships and about one-third described outgoing residents as highly proficient in community medicine competencies. Program-level continuity in community partnerships was significantly correlated to high quality partnerships (odds ratio [OR] 3.51, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.79-6.89, P<0.001) and educational outcomes (OR 2.85, 95% CI 1.38-5.89, P=0.005), while resident-level continuity was not.

Conclusions: Our findings support the importance of continuity to the quality of family medicine residency community partnerships as well as resident education in community medicine. Further research is needed to understand the importance of continuity at the program level versus individual resident level.

Family medicine recognizes the impact of communities on the health of individuals and populations.1 Different approaches used by family medicine residency programs in community medicine (CM) training include episodic, block rotation, and longitudinal experience. These may include participating in nonclinical community events, ongoing community projects, scholarly community projects,2 and providing episodic or longitudinal patient care.

Despite the challenge of time limitations, family medicine program directors endorsed CM training as a high priority.3 Understanding constructs of community engagement is important in designing CM curricula. Key components of community engagement: clear mutual expectations, equity, open exchange of information and resources and “bidirectionality,” meaning mutual and shared commitments and benefits for both the academics and community members.4 Continuity of engagement facilitates the development of stronger partnerships through the fostering of mutual expectations, equity, and bidirectionality.

Prior research suggests a relationship between resident participation in a longitudinal CM experience and exceptional competency in community medicine.5 While a small number of residency programs developed longitudinal curricula, block rotations remain most prevalent,6 perhaps because the emphasis on continuity in family medicine residencies has focused on the outpatient continuity clinic experience.7

The objective of this study was to investigate the relationship between continuity in family medicine residency programs’ CM curricula two outcomes: (1) program directors’ (PDs) reports of high quality partnerships, and (2) graduating residents with exceptional CM competency.

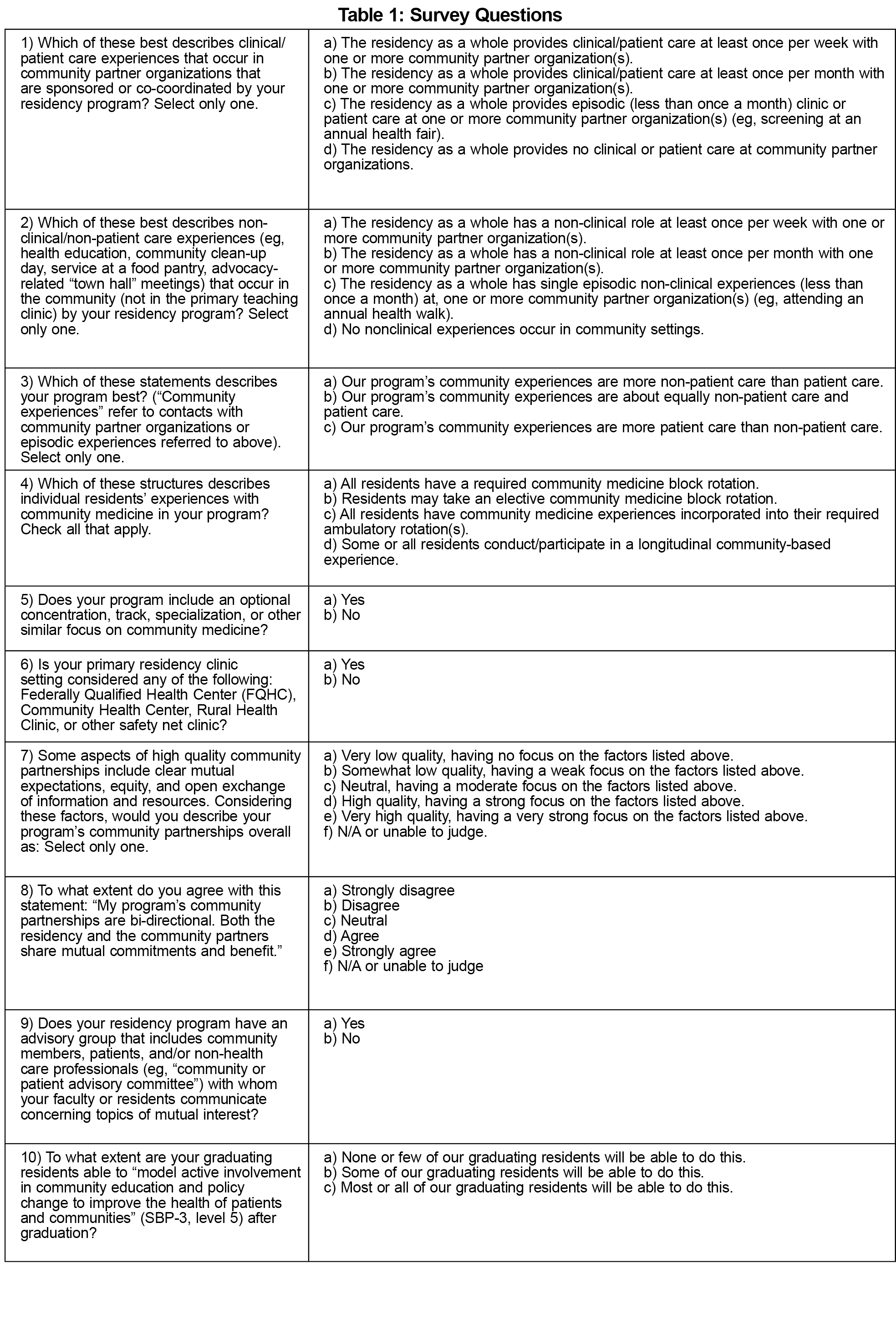

Survey questions were part of a larger omnibus survey of family medicine residency PDs conducted by the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA). We refined survey questions using expert feedback and pretesting with experienced family medicine residency educators. The American Academy of Family Physicians IRB approved the project in December 2015. Data were collected from December 2015 to January 2016.

Electronic surveys were sent to all ACGME-accredited US family medicine residency PDs as identified by the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors. Three follow-up reminder emails were sent, yielding an overall response rate for the survey of 49.2% (227/461).

Ten questions comprised the community medicine survey (Table 1). The study team operationalized key terms within the survey to support consistent interpretation, for example defining high quality partnerships (see question 7, Table 1). We used descriptive statistics to identify the types of experiences and extent of continuity in programs’ CM curricula. Using logistic regression, we tested the association between continuity of programs’ involvement with the community and the quality of community partnership. We created a dichotomous partnership quality outcome variable by combining high and very high quality responses compared to the other responses, then examined program and resident-level continuity as predictors of partnership quality. Program continuity was defined as performing clinical and/or nonclinical activities with community organizations at least monthly. Individual resident continuity was defined as participating in a longitudinal community-based experience. Our multivariate analysis adjusted for partnership bidirectionality and having a safety net family health center.

We also used logistic regression to examine the relationship between continuity in CM partnerships and PD-reported outgoing residents with exceptional CM competency.

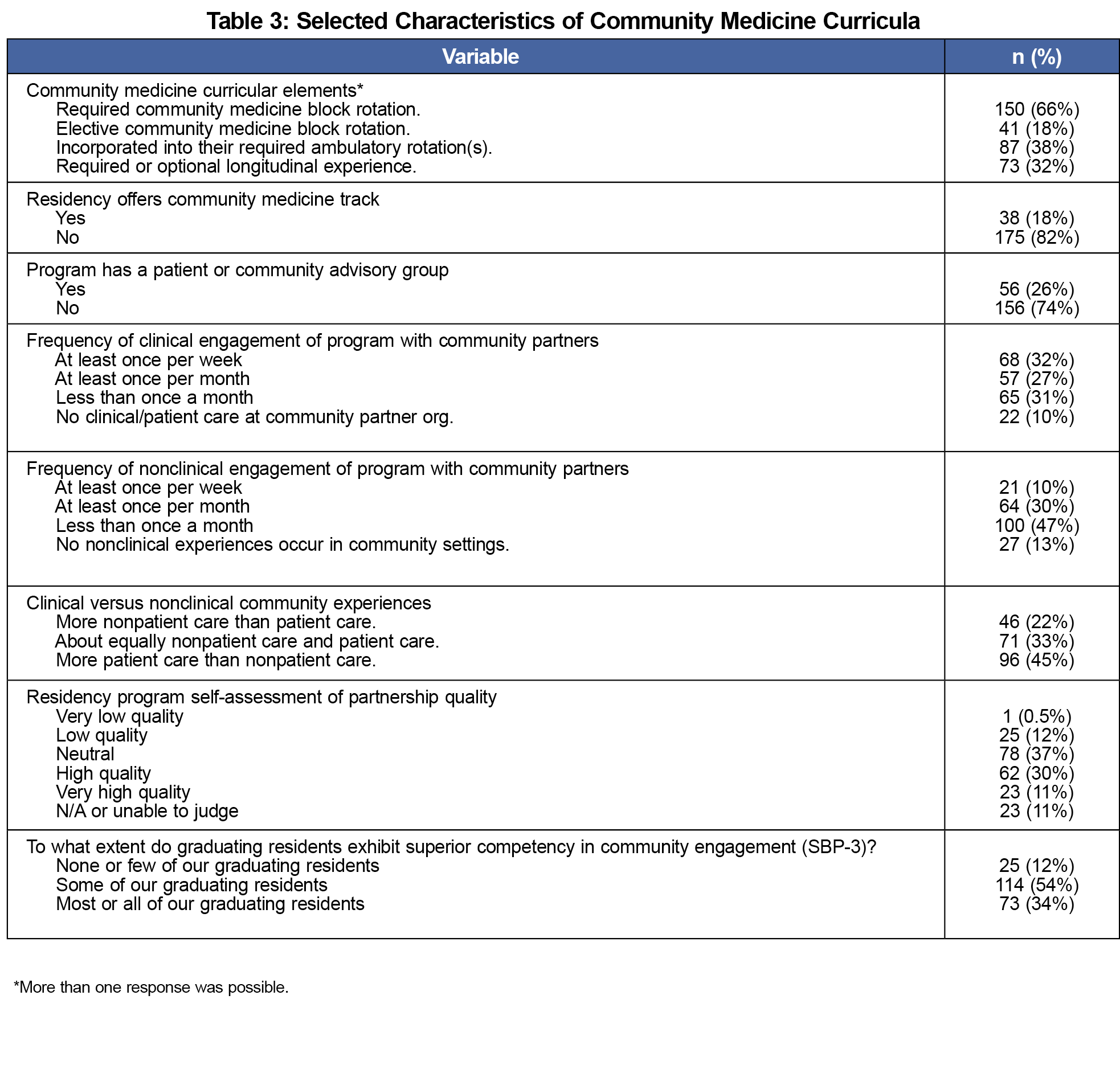

Survey respondents represented a well-mixed national sample of family medicine residency programs (Table 2). The most common CM curricular elements were required block rotations (66%) and incorporation of CM into required ambulatory rotations (38%). Thirty-two percent of PDs reported that some or all residents conducted longitudinal community-based experiences. A CM track or concentration was reported by 18% of programs. Overall, 67.1% of programs met the definition for continuity with community partnerships. Forty-five percent of PDs reported primarily patient care community experiences compared to 22% reporting primarily nonpatient care experiences. Forty-five percent of PDs reported high or very high quality community partnerships, and 61% described their partnerships as bidirectional. Thirty-four percent of PDs reported that most or all of their outgoing residents "model active involvement in community education and policy change to improve the health of patients and communities" (Systems Based Practice Family Medicine Residency Milestone 3e [SBP-3], level 5) after graduation (Table 3).

Continuity in community partnerships at the residency program level was found to be a significant predictor of high quality community partnerships (Odds ratio [OR] 3.51, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.79-6.89, P<0.001), while presence of a longitudinal resident experience was not. Programs with a safety net clinic family health center were less likely to report high quality community partnerships (OR 0.35, 95% CI 0.17-0.73, P=0.005).

The presence of continuity in community partnerships at the program level was positively associated with exceptional outgoing residents in CM competencies (OR 2.85, 95% CI 1.38-5.89, P=0.005). The presence of a longitudinal community experience was not correlated with a high proportion of outgoing residents meeting Level 5 on SBP-3. Further, the presence of a CM track was negatively associated with graduating highly proficient residents in CM (OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.22-0.98, P=0.045). These findings are summarized in Table 4.

Continuity in community partnerships at the program level was found to be a significant predictor of educational outcomes, while the presence of individual resident longitudinal experiences was not. Bidirectionality was confirmed as a strongly positive correlate to PDs assessment of high quality family medicine residency community partnerships.

We note several unexpected findings. PDs of programs located in safety net clinics reported lower quality community partnerships. Possible explanations include programs’ emphasis on clinical service over community partnerships, or a higher bar for rating community partnership quality. Future research evaluating community partnerships and educational outcomes of teaching health centers is needed, as training in these settings is correlated with future practice in underserved settings.8

The negative correlation between presence of a CM track and our educational outcome was also unexpected. We chose a Milestone as an educational outcome measure because this theoretically could be assessed consistently by PDs. However, the large proportion of residents rated at Level 5 suggests unintended or uneven application of the assessment.

Additional limitations include a moderate response rate, the potential bias in the use of PD self-assessment of partnership quality (which may not reflect the community partners’ perspectives), and the lack of consensus on community partnership related terms, limiting survey precision. While reporter bias by PDs is a limitation, we did attempt to mitigate this through the use of a universal Milestone and by providing definitions of key terms. Program directors are frequently utilized as key informants in residency surveys and allow for a national sample of residency programs.

This study specifically examined the role of continuity on the strength of residency community medicine partnerships and resident community medicine competency. Further research could explore additional contributing factors, including some of the other program and curriculum characteristics we gathered in this survey, such as the impact of the clinical versus nonclinical resident activities and the presence of a patient advisory committee.

Next steps would include investigating individual resident-level outcomes to clarify the importance of resident versus program-level continuity and directly evaluate community medicine expertise, identifying strategies to increase continuity in residency-community partnerships, and exploring the perspectives of community partners.

References

- Willard W, Johnson A, Wilson V. Meeting the Challenge of Family Practice. Chicago, Illinois: American Medical Association; 1966.

- Moushey E, Shomo A, Elder N, O’Dea C, Rahner D. Community partnered projects: residents engaging with community health centers to improve care. Fam Med. 2014;46(9):718-723.

- Vickery KD, Rindfleisch K, Benson J, Furlong J, Martinez-Bianchi V, Richardson CR. Preparing the Next Generation of Family Physicians to Improve Population Health: A CERA Study. Fam Med. 2015;47(10):782-788.

- Ahmed SM, Palermo A-GS. Community engagement in research: frameworks for education and peer review. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(8):1380-1387.

https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.178137.

- Plescia M, Konen JC, Lincourt A. The state of community medicine training in family practice residency programs. Fam Med. 2002;34(3):177-182.

- Reust CE. Longitudinal residency training: a survey of family practice residency programs. Fam Med. 2001;33(10):740-745.

- Bowen JL, Hirsh D, Aagaard E, et al. Advancing educational continuity in primary care residencies: an opportunity for patient-centered medical homes. Acad Med. 2015;90(5):587-593.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000589.

- Phillips RL, Petterson S, Bazemore A. Do residents who train in safety net settings return for practice? Acad Med. 2013;88(12):1934-1940.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000025.

There are no comments for this article.