Introduction: Residency training is a peak time of physician distress, but also a venue in which residents can learn skills to thrive in a high-risk career. The goal of this study was to examine residents’ perceptions of the value of teaching wellness as an integrated component of a residency program.

Methods: Researchers at the University of Utah Family Medicine Residency Program conducted a focus group with graduating family medicine residents regarding their perception of wellness and wellness skills, after having completed an intentional wellness curriculum integrated through their 3 years of residency. We used open coding to identify themes of the residents’ perceptions of the wellness curriculum.

Results: Four interconnected themes emerged: (1) describing the relevance of wellness to a medical career; (2) the wellness curriculum as prioritized and intentional; (3) The value of wellness skills learned through the curriculum; and (4) the role of community ethos in maintaining wellness.

Conclusions: Residents consider wellness to be a critical facet of being an effective physician. Our results suggest that a culture of wellness can be created through deliberate and transparent curricular design, helping residents to view wellness as a priority.

Medicine is a high-risk career, and residency training is a peak time of physician distress. Rates of burnout and depression are as high as 50%, and higher than the general population at all stages of medical training.1 Medical residency is an ideal time to teach skills for coping with a high-stress profession, and evidence suggests that training programs can actively promote an environment that protects against burnout.2-4 The goal of this study was to understand how family medicine residents view wellness, and what they value from a wellness curriculum.

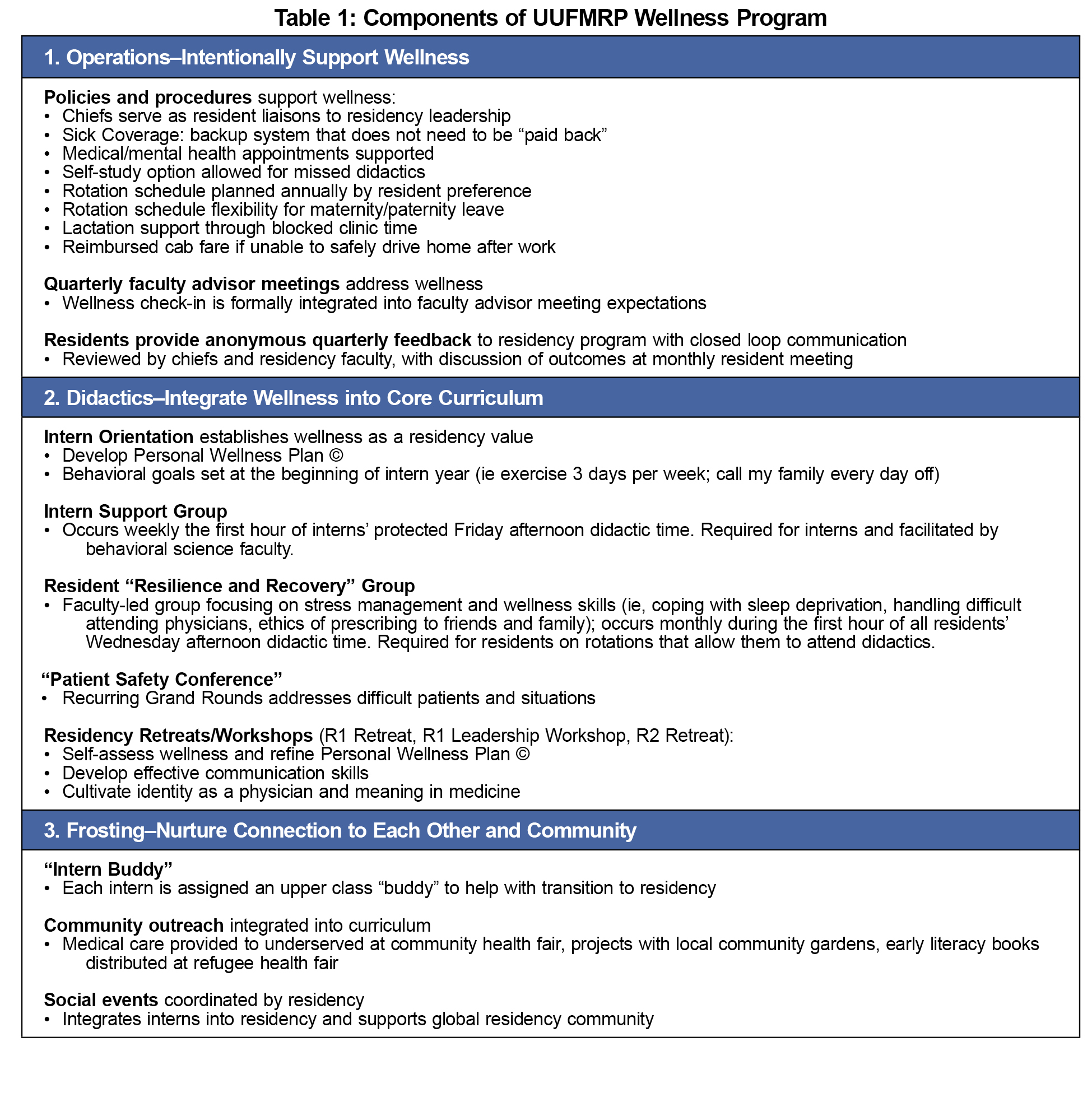

At the University of Utah Family Medicine Residency Program (UUFMRP), we have integrated wellness across training, utilizing principles of positive psychology.5 The UUFMRP is a community-based, university-affiliated family medicine residency program with 24 residents (eight residents per year). The wellness curriculum includes: weekly support groups for interns during half the year, and a monthly skills-based support group for all residents integrated into weekly didactics; dedicated wellness time at retreats; a resident “buddy” system; frequent wellness check-ins; and protected time for health appointments for residents. The curriculum focuses on: (1) self-assessment skills and goal-setting regarding wellness; (2) managing stresses of residency and future career; and (3) opportunities for enjoyment, engagement and meaning in work through programmatic structured activities. See Table 1 for a description of program components.

To evaluate residents’ perception of the value of an integrated wellness program, including their understanding of wellness and skills that they find useful for future careers, we conducted a focus group with outgoing third-year family medicine residents.

This study sought to understand perceptions of a wellness curriculum and its applicability during a family medicine residency by conducting a focus group with third-year family medicine residents, using phenomenology principles to describe “what [residents] experienced and how they experienced it”.6,7 The eight graduating residents were invited to participate in this optional group, and all eight consented to participate. Dinner was provided, and residents were thanked for their time with a small gift card. We obtained approval from the University of Utah Institutional Review Board, and followed appropriate participant consenting.

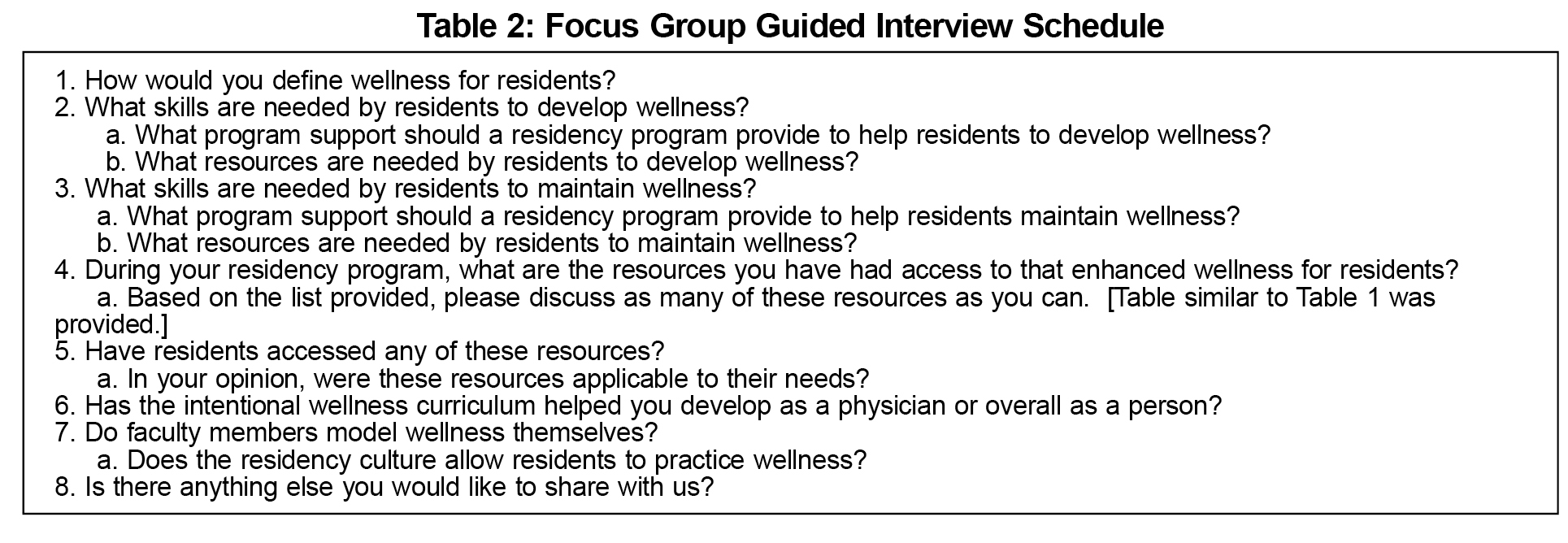

One of the authors (CJF) and a research analyst moderated the focus group using a guided interview schedule (see Table 2); these moderators are not faculty within the department where the residency is located, and are not involved in the wellness curriculum. We asked residents about definitions of wellness, skills needed to promote wellness, and activities they participated in to promote and maintain wellness. A 45-minute audio-recorded focus group was transcribed by a professional transcription service, and the research team checked the transcript twice for accuracy. All three authors independently coded the transcripts, and met twice to co-identify themes from the transcript, resolving any conflicts among codes through in-depth discussion. We used open coding initially for analysis, and moved to selective coding around themes from the transcript.

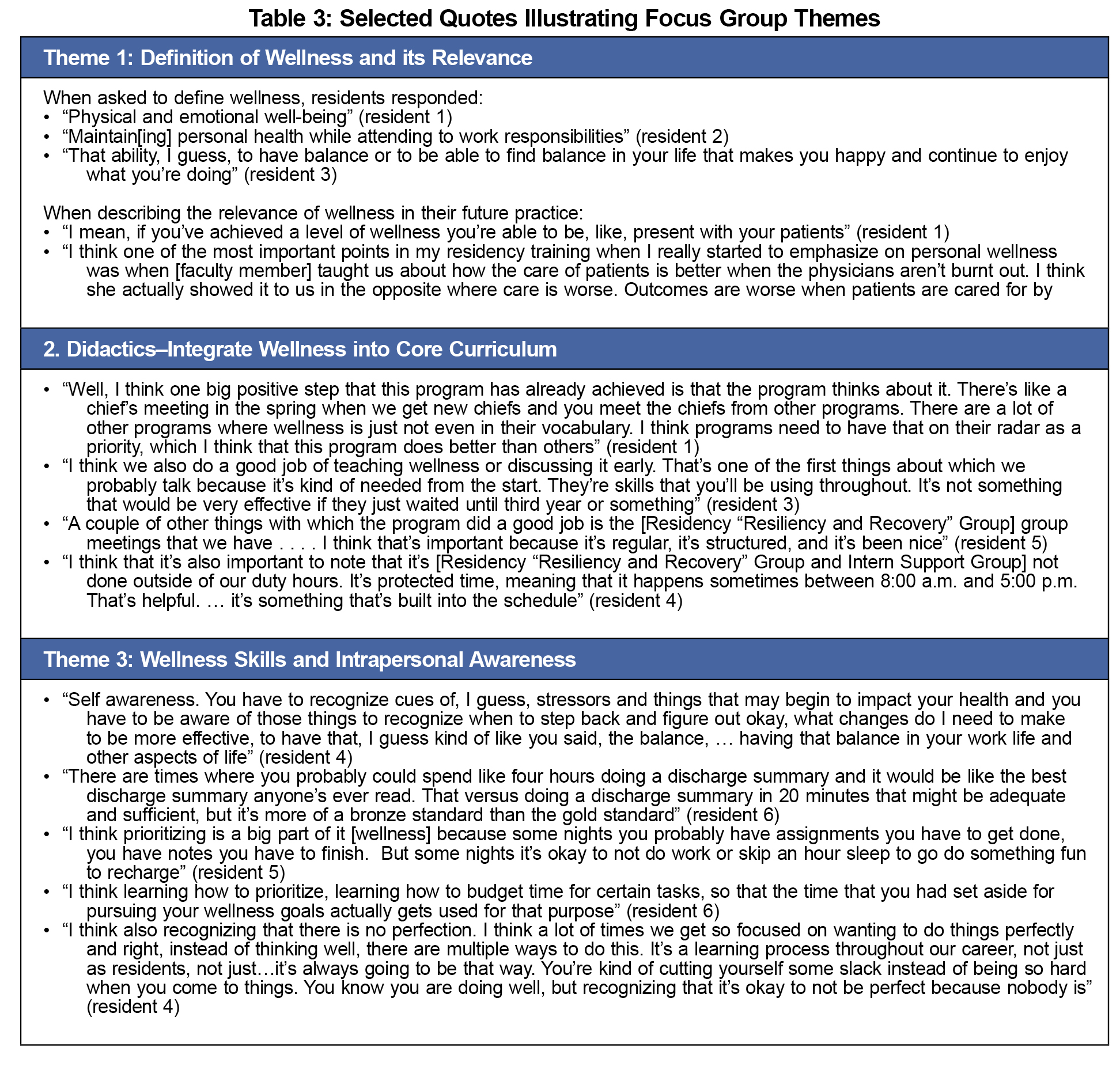

Four interconnected themes emerged from the focus group: (1) residents’ view of wellness, and their understanding of its impact on their current behavior and future career, summarized under “definition of wellness and its relevance”; (2) residents’ perception of how wellness was promoted through the residency curriculum, including the extent to which the program prioritized wellness intentionally (ie, dedicated programmatic and faculty time), summarized under “wellness curriculum is prioritized and intentional”; (3) wellness skills that residents identified as having learned through the wellness program, such as techniques for maintaining personal and professional resiliency, effective coping, and maintaining optimal patient care through difficult times, summarized under “wellness skills and intrapersonal awareness”; and 4) role of the community and interpersonal relationships in wellness, including health of the overall group, summarized under “interpersonal culture of wellness”

Example quotes from focus group participants are shown in Table 3 to illustrate these themes and highlight how they connect to the program's wellness curriculum and link to residents' view of their own wellness behaviors.

This qualitative study examined family medicine residents’ perceptions of the value of an integrated wellness program. First, wellness is considered a critical facet of an effective physician. The residents described how attention to wellness was relevant to personal and professional satisfaction, improved patient outcomes, and continuing as a physician. Second, a culture of wellness can be created through deliberate, transparent curricular design. Many facets of this wellness program are commonplace; however, the focus group emphasized the importance of making wellness a program priority by allocating time (our most precious resource) to wellness. Optional after-hours activities are not sufficient; rather, including wellness into the overall curriculum structure highlights wellness as a program priority. Third, residents identified intrapersonal skills of self-awareness and self-management as paramount in cultivating their own wellness. Our curriculum is heavily skills based, and participant comments suggested that they have integrated these skills into their lives. Role-modeling, peer and faculty support, and a sense of responsibility to one another were important factors in creating an ethos of wellness.

This study is limited by small sample size and reflects the views of residents at a single institution. Focus group responses may have been biased by primarily positive framing of questions, or by knowledge that residency faculty were organizing the study; however questions were open ended and the focus group was led by individuals unaffiliated with the residency. It will be critical to understand how residents in different programs with various curricula view wellness. Despite these limitations, the residents’ descriptions demonstrated the value ascribed to an intentional wellness component embedded within training. The themes described provide a framework that can be employed by other programs intent on understanding the value of wellness activities.

In conclusion, residency training is the primary venue for teaching wellness as a foundational skill for a successful medical career. To create a culture of wellness, residencies should be intentional about integrating wellness curricula from the first day of training. Residents view wellness as a priority when program time is dedicated to the curriculum, and when it is part of the program vocabulary. Components of a wellness curriculum are relatively simple to implement, and many residency programs have many components already in place. Focus group participants articulated that introducing wellness early and reinforcing wellness longitudinally is likely an effective means to cultivate long-term provider wellness.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Lisa Gren, PhD, MSPH, for her thoughtful comments on the manuscript.

Financial Support: This study was supported by Health Studies Fund, Department of Family and Preventive Medicine, University of Utah.

Presentations: The content of this manuscript was presented at the Forum for Behavioral Science in Family Medicine, Chicago, IL, September 2016.

References

- Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele, D et al. Burnout among US medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014; 89: 443-451.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134.

- Olson K, Kemper KJ, Mahan JD. What factors promote resilience and protect against burnout in first-year pediatric and medicine-pediatric residents? J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2015; 20: 192-198.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2156587214568894.

- Prins JT, Hoekstra-Weebers JEHM, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, et al. The role of social support in burnout among Dutch medical residents. Psychol Health Med. 2007;12:1-6.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500600782214.

- Ripp J, Babyatsky M, Fallar R, et al. The incidence and predictors of job burnout in first-year internal medicine residents: A five-institution study. Acad Med. 2011; 86: 1304-1310.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822c1236.

- Seligman MEP, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology: an introduction. Am Psychol. 2002; 55: 5-14.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5.

- Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2013.

- Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 4th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage; 2009.

There are no comments for this article.