Introduction: Decreased vaccination rates in children have played a role in the deaths of several children in the United States over the last decade. Interventions to date have been ineffective at changing vaccination patterns. No studies have evaluated a conciliatory patient-centered approach where parent concerns were acknowledged and addressed in a group setting.

Methods: Vaccine-averse parents with incompletely vaccinated children were recruited from a family medicine practice. These parents attended three group visit sessions centered on vaccine safety and efficacy. Pre and post surveys were given at each session. The children’s vaccination records were examined in the year prior and the year following the groups. One year after the group visits, parents were interviewed about their attitudes toward vaccination.

Results: There were no significant attitude changes in parents attending the group visits. In the year following the visits, the percentage of recommended vaccines that children had received did not increase. Interviews with parents revealed a broad range of concerns about vaccines and a widespread desire for a longer-term study designed to address these concerns.

Conclusions: Surveys and vaccination records revealed no significant change in attitudes or behavior after three group visit sessions, consistent with other research on interventions with vaccine-averse parents. The phone interviews demonstrated a desire for further research into long-term effects of vaccines, with most parents stating that they would consider changing their beliefs if the research was free from commercial bias, addressed their concerns, and was extended out over a long period of time.

Vaccinations are one of the most successful public health interventions, saving an estimated 2 to 3 million lives every year.1 Despite this, there has been an increase in parental concern regarding childhood vaccines in the United States.2,3 This has led to reduced vaccination rates in certain communities, which has played a role in recent disease outbreaks resulting in several deaths.4,5 The vaccination rate nationwide for seven common vaccines (DTaP, MMR, polio, Hib, varicella, and PCV) for children aged 19 to 35 months was 72.2% in 2015, and was 78.5% in Massachusetts.6

Parental reasons for vaccination nonadherence include concerns about the risk of adverse effects, chemicals used in vaccines, use of fetal stem cell lines in vaccine production, and others.7 Though many studies have tried to address vaccine hesitancy, a meta-analysis in 2013 found no evidence that interventions had any positive effect.8 In fact, directly challenging parents’ viewpoints can lead to reduced intent to vaccinate.9

To date, no studies have tried a conciliatory approach in which patients’ specific concerns were not dismissed and were the focus of the discussion. We hypothesized that the increased rapport associated with this approach might make patients more likely to modify their stance on vaccination.

Subjects were recruited by creating a registry of children who were behind on their vaccines and who were patients at Family Practice Group (FPG) in Arlington, Massachusetts. Parents of these children were invited to participate in a three-session group visit series. This process yielded six mothers with a total of 12 children from 2 months to 6 years old. Two additional children were born the following year. These parents attended some or all of three 1-hour group sessions, which were held at FPG on a weekday evening.

During each session, participants received handouts addressing specific vaccines.10 Participants were given a chance to read each handout, and to voice concerns they had about each vaccine. Their questions were answered, followed by discussion on vaccine-preventable diseases and the vaccines themselves. Anticipated concerns of the parents regarding each vaccination were addressed.7 Before and after each group session, participants completed a Likert-scale survey on safety and efficacy of the vaccines discussed and intent to vaccinate.

Participants were given letter codes to protect identity. Participant codes were the same for pre and post surveys in each individual session, but each participant’s code was not the same across sessions.

Responses to the 40 questions in the pre- and post-session surveys were analyzed, with the average, standard deviation, and P-value calculated for each question. The average, standard deviation, and P-value of the pooled answers were calculated also.

One year after the completion of the three monthly group sessions, we accessed the vaccination records of the participants’ children. Percentages of vaccines recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that were administered at the start of the sessions, as well as 1 year later, were calculated for each child. The recommended total for each child was calculated using the CDC vaccination schedule.11

Four of the six participants completed a 30-minute phone interview about attitudes toward vaccination 1 year after the group visit sessions. We also interviewed one parent who was invited to attend the group visits but could not. The interviews were recorded and coded by a member of the research team using the interview guide as a template.

Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained from the Tufts University IRB.

Survey response rates at each session were 100%, although not every parent was able to come to every session.

Only two out of 40 survey questions showed a statistically significant difference in response between the pre- and post surveys (P < 0.05). These questions were “Do you trust doctors’ information on vaccines?” (P=0.03) and “Is the Hepatitis A vaccine safe?” (P=0.03). The post-survey responses for these two questions displayed a more favorable attitude regarding vaccines. Pooled responses to all questions also revealed more favorable attitudes toward vaccines, with the average increasing from 4.02 to 4.39 (P=0.04).

The average number of vaccines given per child modestly increased from 6.14 before the groups to 7.00 one year after, but the number of recommended vaccines increased substantially. As such, the percentages of recommended vaccines that the average child received decreased from 36% to 33%.

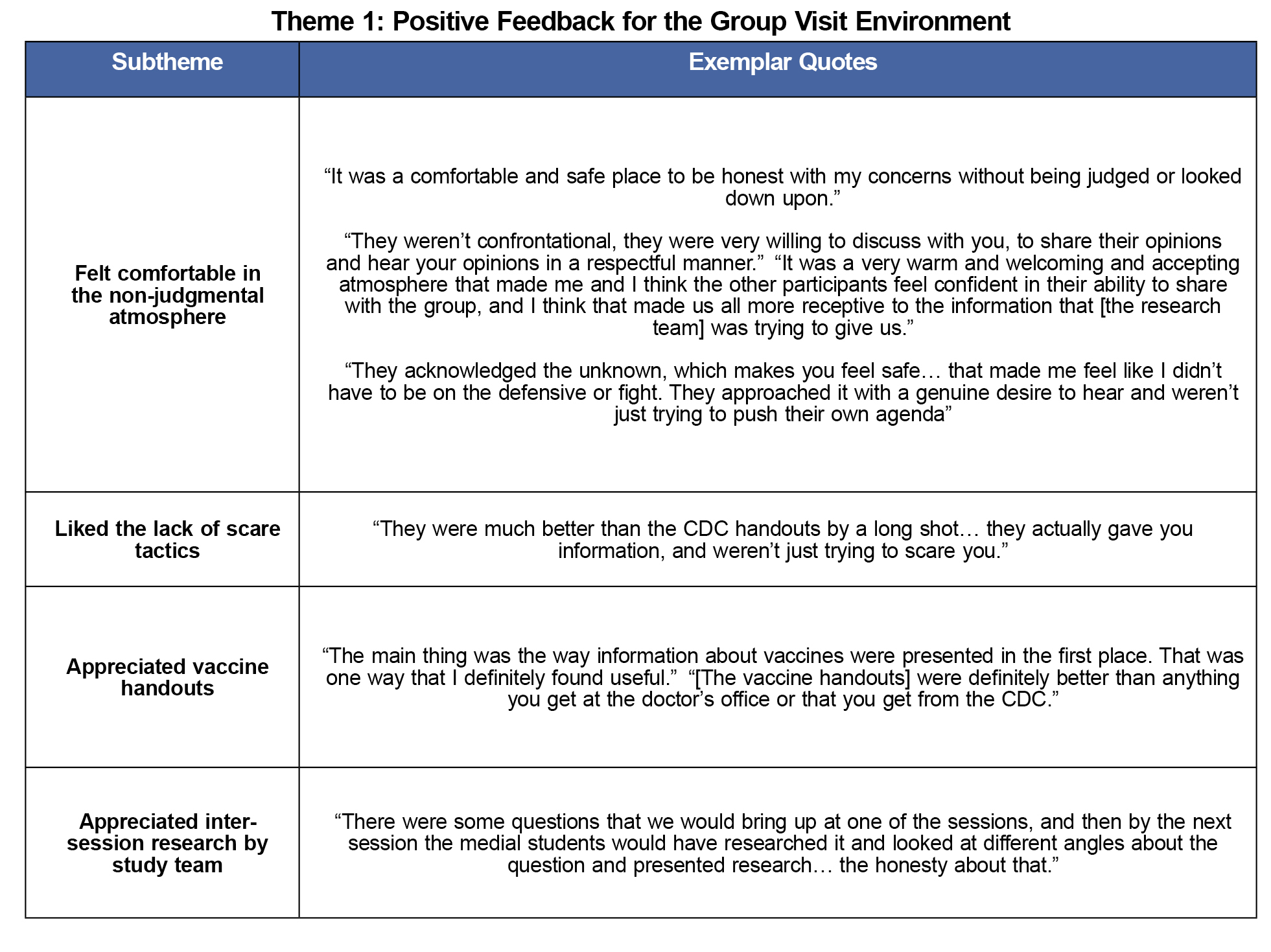

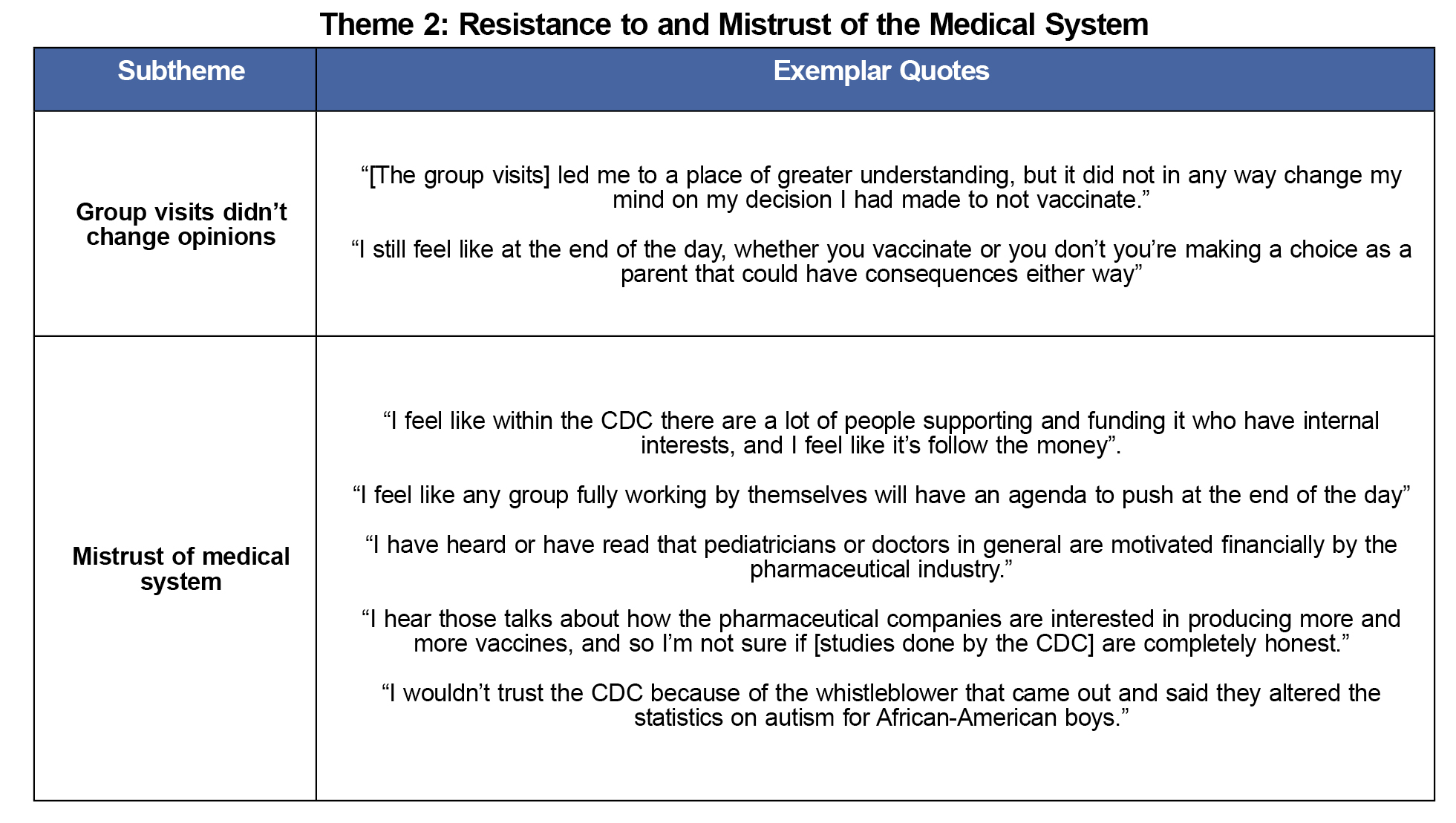

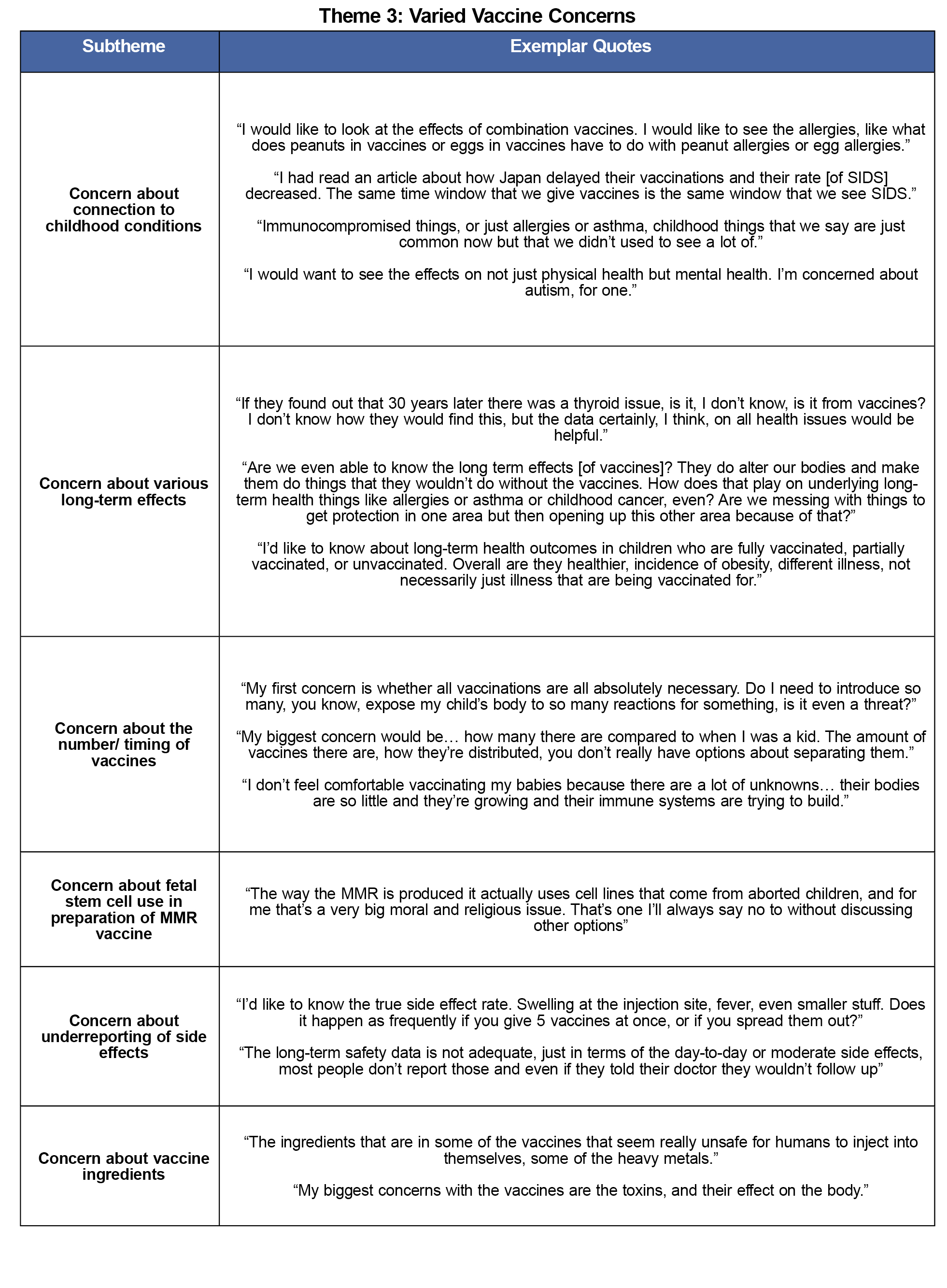

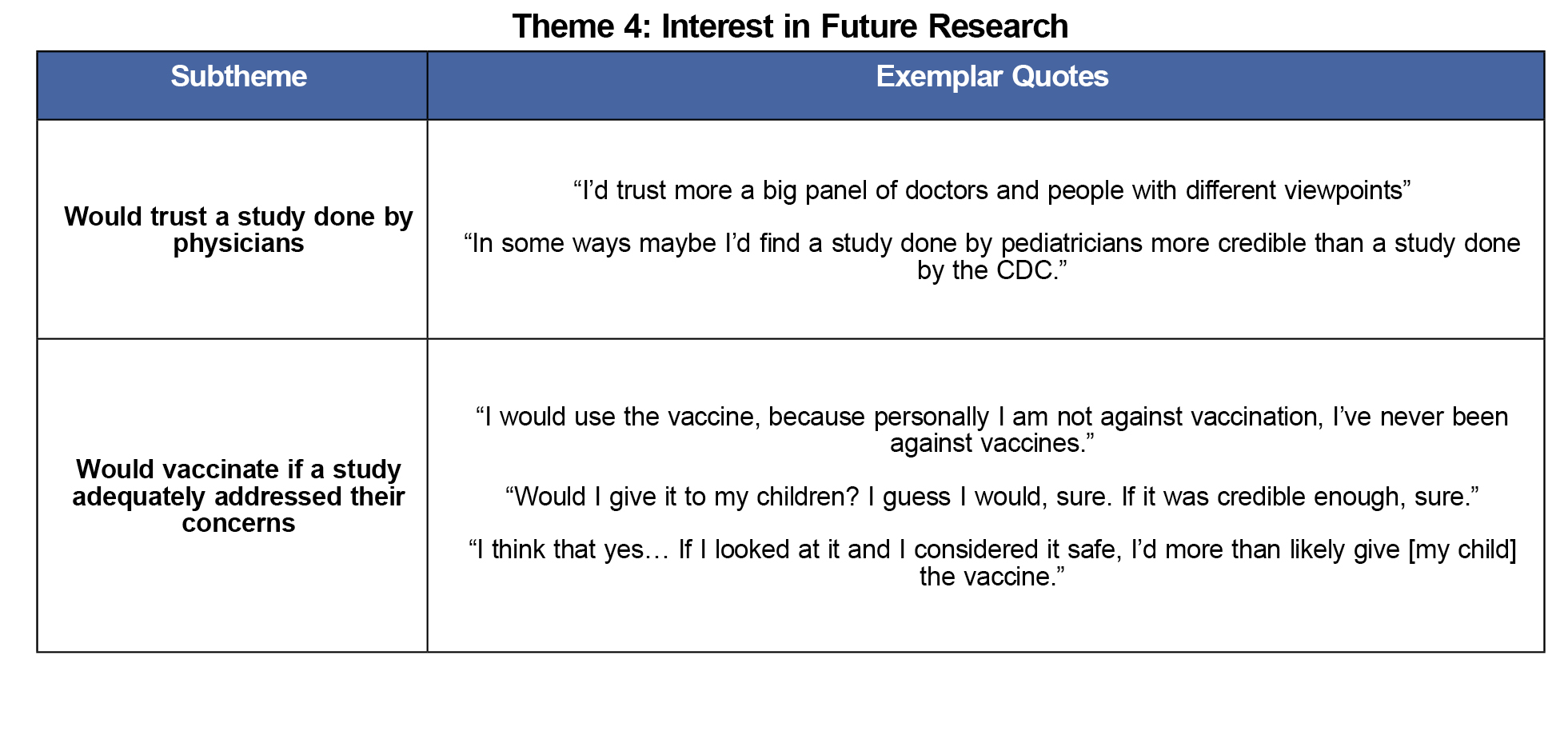

The majority of participants were appreciative of the group visits, but left with similar concerns to when they arrived. All parents expressed a desire for further research addressing a wide variety of concerns about vaccine safety or efficacy. Four themes emerged from the phone interviews, which are outlined in Tables 1 through 4 below.

Theme 1: Positive Feedback for the Group Visit Environment

There was universal expression of appreciation for the creation of a safe place for parents to discuss their concerns about vaccines without fear of judgment. Parents also spoke highly of the vaccine handouts and the efforts by research staff to answer any questions parents had between group visits.

Theme 2: Resistance to and Mistrust of the Medical System

Most participants expressed concern that current scientific literature on vaccines could not be trusted, as much of it was conducted by researchers with ties to the pharmaceutical industry. Most also said that while they appreciated the group visits, they did not intend to change their vaccination behavior as a result.

Theme 3: Varied Vaccine Concerns

Parents cited a wide variety of concerns with vaccines. These ranged from unknown short-term and long-term effects to religious concerns over the use of fetal stem cells in vaccines. Some parents were concerned that vaccine side effects are underreported and expressed a desire for more accurate data.

Theme 4: Interest in Future Research

All participants expressed an interest in obtaining further data on vaccines, with most saying that they would trust a study done by physicians without pharmaceutical ties and that they would follow the results of such a study if it addressed their most pressing concerns.

The qualitative section of the study failed to demonstrate any change in vaccination behavior over the course of the study, though there was a statistically significant increase in overall favorability toward vaccines. The two individual questions with statistically significant responses were likely due to Type I error, given that 5% of the 40 questions had P-values under 0.05, the same number as expected by chance.

There are several possible reasons for lack of an observed effect. The study was underpowered, with a sample size of six. It’s also possible that this type of intervention, like many others in the literature, is not effective in changing vaccination behaviors in this population. Further, it could be that holding the vaccine counseling in a group visit setting as opposed to one-on-one increased the sense of community and resolve across the participants, and negated any effect that the nonconfrontational atmosphere had. Additionally, responses over time could not be linked within each individual respondent, due to the need to preserve anonymity. The quantitative analysis, therefore, violates statistical assumptions of independence of measurements, which should be considered as an additional limitation of the study.

The qualitative portion of the study revealed that there was great appreciation for health professionals who worked to hear the concerns of vaccine-averse parents and listen to what they had to say. While this approach may not change opinions on vaccines, it does seem to increase feelings of trust and rapport with parents.

The interviews also showed that there was a strong desire among this group for research addressing their specific concerns about potential vaccine side effects. At the same time, it showed that many of the sources for data that physicians rely on might not be viewed as reliable by this population. There was widespread skepticism about studies funded solely by the CDC or National Institutes of Health (NIH), with four of the five mothers expressing concerns that such research would be subject to bias due to perceived CDC and NIH ties to the pharmaceutical industry. All of the parents expressed interest in a large, longitudinal study designed with input from vaccine-averse parents as well as pediatricians and family physicians. Additionally, the funding sources would have to be free from perceived pharmaceutical ties.

Future studies conducted in line with these criteria (without industry, CDC or NIH funding, and with parent engagement) may be better received by vaccine-averse parents, and could potentially change the vaccination patterns of vaccine-averse parents and reduce morbidity and mortality related to vaccine aversion. More research is needed to explore this possibility in detail.

References

- World Health Organization. World Immunization Week 2012. http://www.who.int/immunization/newsroom/events/immunization_week/2012/further_information/en/. Published April 21, 2012. Accessed November 19, 2015.

- Chen RT, DeStefano F, Pless R, Mootrey G, Kramarz P, Hibbs B. Challenges and controversies in immunization safety. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2001;15(1):21–39.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-5520(05)70266-X.

- Chen RT, Hibbs B. Vaccine safety: current and future challenges. Pediatr Ann. 1998;27(7):445–55.

https://doi.org/10.3928/0090-4481-19980701-11.

- Feikin DR, Lezotte DC, Hamman RF, Salmon DA, Chen RT, Hoffman RE. Individual and community risks of measles and pertussis associated with personal exemptions to immunization. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;284(24):3145–50.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.24.3145.

- Salmon DA, HaberM, Gangarosa EJ, Phillips L, Smith NJ, Chen RT. Health consequences of religious and philosophical exemptions from immunization laws. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;282(1):47–53.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.1.47.

- "Combined 7-vaccine Series Vaccination Coverage among Children 19-35 Months by State, HHS Region, and the United States, National Immunization Survey (NIS), 2015." 2015 Childhood Combined 7-vaccine Series Coverage Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/childvaxview/data-reports/7-series/reports/2015.html. Published 6, 2016. Accessed March 31, 2017.

- Systematic review of qualitative studies exploring parental beliefs and attitudes toward childhood vaccination identifies common barriers to vaccination. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2005; 50: 1081-1088.

- Sadal, A., Richards, J., Glanz, J., Salmon, D., & Omer, S. (2013). A systematic review of interventions for reducing parental vaccine refusal and vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine, 31(40), 4293-4304.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.07.013.

- Nyhan B, Reifler J, Richey S, & Freed GL. Effective Messages in Vaccine Promotion: A randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2014; 1098-4275.

https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-2365.

- Altman W, Quinn M, Potter N. Immunization Handouts, Tufts University School of Medicine TUSK. (2014). http://tusk.tufts.edu/view/content/Medical/3052/2035243. Accessed October 5, 2016.

- Birth-18 Years & "Catch-up" Immunization Schedules. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/child-adolescent.html. Published April 20, 2016. Accessed August 1, 2016.

There are no comments for this article.