Background: Integrating behavioral and primary care practices improves quality of care, but limited data exists regarding the extent or attributes of such integration. We conducted a baseline evaluation of the level and characteristics of integrated practices in Rhode Island.

Methods: The Rhode Island Department of Health 2015 Statewide Health Inventory Behavioral Health Survey was sent to behavioral health clinics and outpatient psychiatry and psychology practices. Survey questions assessed indicators of integration, including colocation, shared electronic medical records (EMRs), and shared communication systems.

Results: Only 19%, 9%, and 17% of behavioral health clinics, psychiatrists, and psychologists, respectively reported any integration with primary care practices. Compared to psychology (3.5%) and psychiatry (0.0%) practices, behavioral health clinics reported the highest level of practice colocation (10.4%, P<0.05). Compared to non-colocated practices, colocated behavioral health clinics reported higher levels of integration by other indicators, including shared EMRs (33.0% vs 0.0%, P=0.01).

Conclusion: This statewide survey demonstrated that limited integration exists between behavioral health and primary care practices in Rhode Island, and that such integration has a range of characteristics and levels. More practice integration is needed to ensure the delivery of high-quality, evidence-based care to the millions of individuals living with cooccurring behavioral and physical health needs.

About 18% of US adults—over 44 million people—have a diagnosable behavioral health condition.1 The majority are treated by primary care rather than behavioral health clinicians, yet primary care clinicians may not have the time, support, or expertise to care for these patients alone.2 Conversely, patients with behavioral health conditions treated primarily at behavioral health practices often have poor physical health outcomes.3 Integrating primary and behavioral health care, in either setting, has been shown to improve both physical and mental health outcomes for complex patients, reduce the overall cost of their care, and enhance patient and clinician satisfaction.2,4-6

Behavioral health integration is defined as care provided by both primary and behavioral health clinics, working together to address medical and mental health disorders, substance use, and chronic illness self-management.7 Models of integration are variable in practice, but may include factors such as colocation,7,8 shared communication systems, and shared electronic medical records (EMRs).3 Some practices may define integrated care as consults between geographically distinct clinicians while others may define integration as colocated care with behavioral health and primary care clinicians working together in teams.9-11 Colocation has many benefits associated with close proximity of multidisciplinary team members, including improved clinician communication and ease of services for patients. However, colocation itself does not necessarily indicate fully integrated primary care and behavioral health services.11

Integrating behavioral and primary care has proven benefits, but limited data exists regarding where and how practices are integrating,12,13 which hinders efforts at planning and executing interventions. We conducted an evaluation of behavioral health practices on the number and characteristics of integrated practices in Rhode Island to both establish a baseline and to help inform efforts to expand integrated care to Rhode Islanders in need.

Study Design

The Rhode Island Department of Health (DOH) 2015 Statewide Health Inventory was legislatively mandated in 2014 to “establish and maintain an inventory of all health care facilities, health services, and institutional health services” in Rhode Island, and consisted of health inventory surveys across 12 components of the health care system, including behavioral health care.14 The Behavioral Health Survey (available on the STFM Resource Library)15 was included in the Statewide Health Inventory to evaluate the availability of mental health and substance use services in the state, including practice integration. Survey questions were modeled after those in the World Health Organization’s Service Availability and Readiness Assessment, and the Mountainview Consulting Group’s Primary Care Behavioral Health Integration Tool (PCBH-IT).16,17 Feedback was solicited from stakeholders including the Rhode Island Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals (BHDDH).

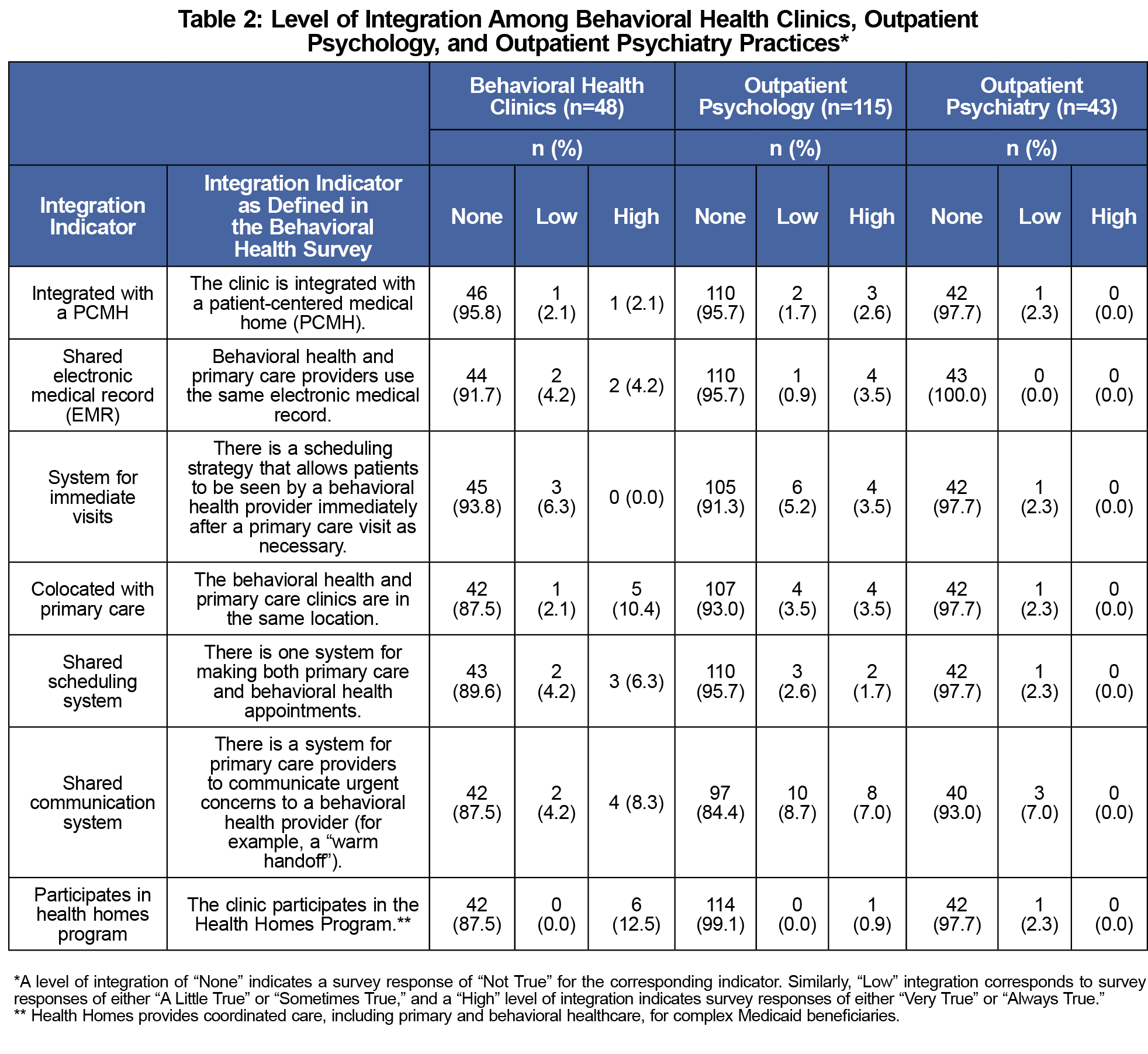

The survey targeted practice administrators at licensed behavioral health clinics, outpatient psychiatry practices, and outpatient psychology practices. When practice administrators were unavailable, clinicians responded to the survey. Licensed behavioral health clinics were defined as clinics that provide mental health and/or substance use services and are staffed by multidisciplinary clinicians including social workers, nurses, and psychologists. Survey questions assessed indicators of integration including colocation, shared electronic medical records (EMRs), integration with a PCMH, shared scheduling and communication systems, and participation in a Health Homes program. Medicaid Health Homes are practices that coordinate care for Medicaid enrollees with complex illnesses, including cooccurring physical and behavioral health needs.18 Survey definitions of integration indicators are included in Tables 2 and 3. Response choices included, Not True, A Little True, Sometimes True, Very True, or Always True for each indicator. Additional details on survey methodology can be found in the Statewide Health Inventory.14

Data Collection

Prior to survey distribution, licensed behavioral health clinics were identified via the BHDDH and psychiatry and psychology practices were identified via publicly available Rhode Island licensure data.

Analysis

The John Snow Research and Training Institute, Inc standardized the data. Survey results for multisite practices that completed a single survey were counted once for each site. Responses were collapsed into three categories indicating no (defined as Not True for the indicator), low (A Little true, or Somewhat True), or high integration (Very True, Always True). We reviewed descriptive data of the number of integrated practices by integration indicator. To test for significant differences in high integration between practice types, we compared high integration groups using Fisher exact tests. Lastly, we compared integration indicators between colocated and non-colocated behavioral health clinics using Fisher exact tests. Analyses were conducted using SAS (Cary, NC). The Rhode Island Department of Health Institutional Review Board deemed this study exempt.

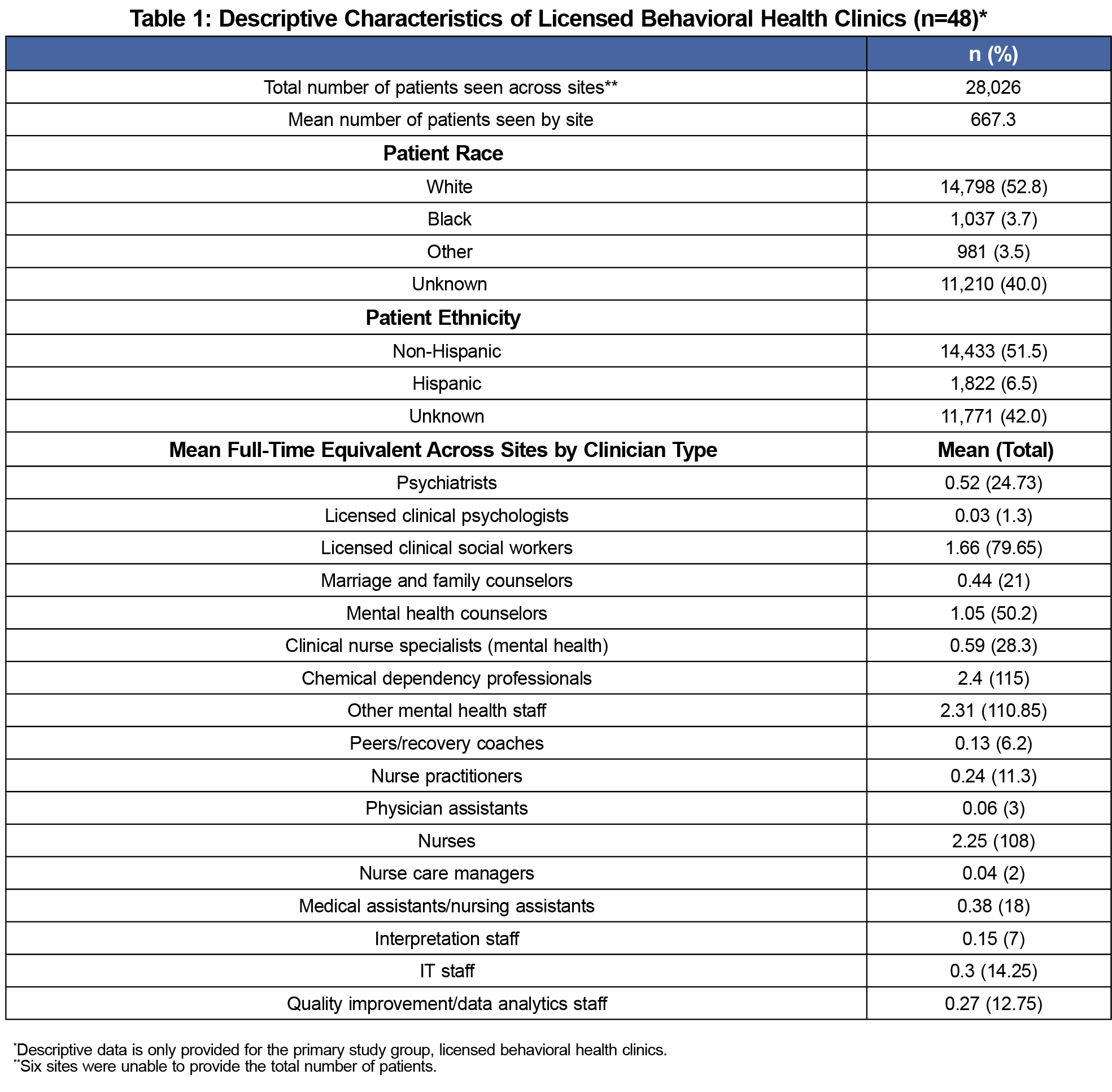

The survey response rate was 48 of 52 behavioral health practices (92%), 43 of 130 outpatient psychiatry practices (33%), and 115 of 480 (24%) outpatient psychology practices. Licensed behavioral health clinics provided care for 28,026 patients. The majority of patients (52.8%) were non-Hispanic white, and 40% of race/ethnicity data was unknown. See Table 1 for characteristics of behavioral health clinics.

Among respondents, 19% of behavioral health, 17% of psychology, and 9% of psychiatry practices reported any integration, indicated by a response of “A Little True,” “Somewhat True,” “Very True” or “Always True” to any variable. All reports of integration by psychiatry practices were marked “Somewhat True.”

More behavioral health clinics reported high integration by colocation with primary care (10.4%) than psychology (3.5%) or psychiatry practices (0.0%, P=0.05; Table 2). Similarly, more behavioral health clinics reported high integration by participation in a Health Homes program (12.5%) than psychology (0.9%) or psychiatry practices (0.0%, P=0.002). More behavioral health clinics also reported high integration by shared EMR, shared scheduling system, and shared communication system, than psychology or psychiatry practices, but these results were not significant.

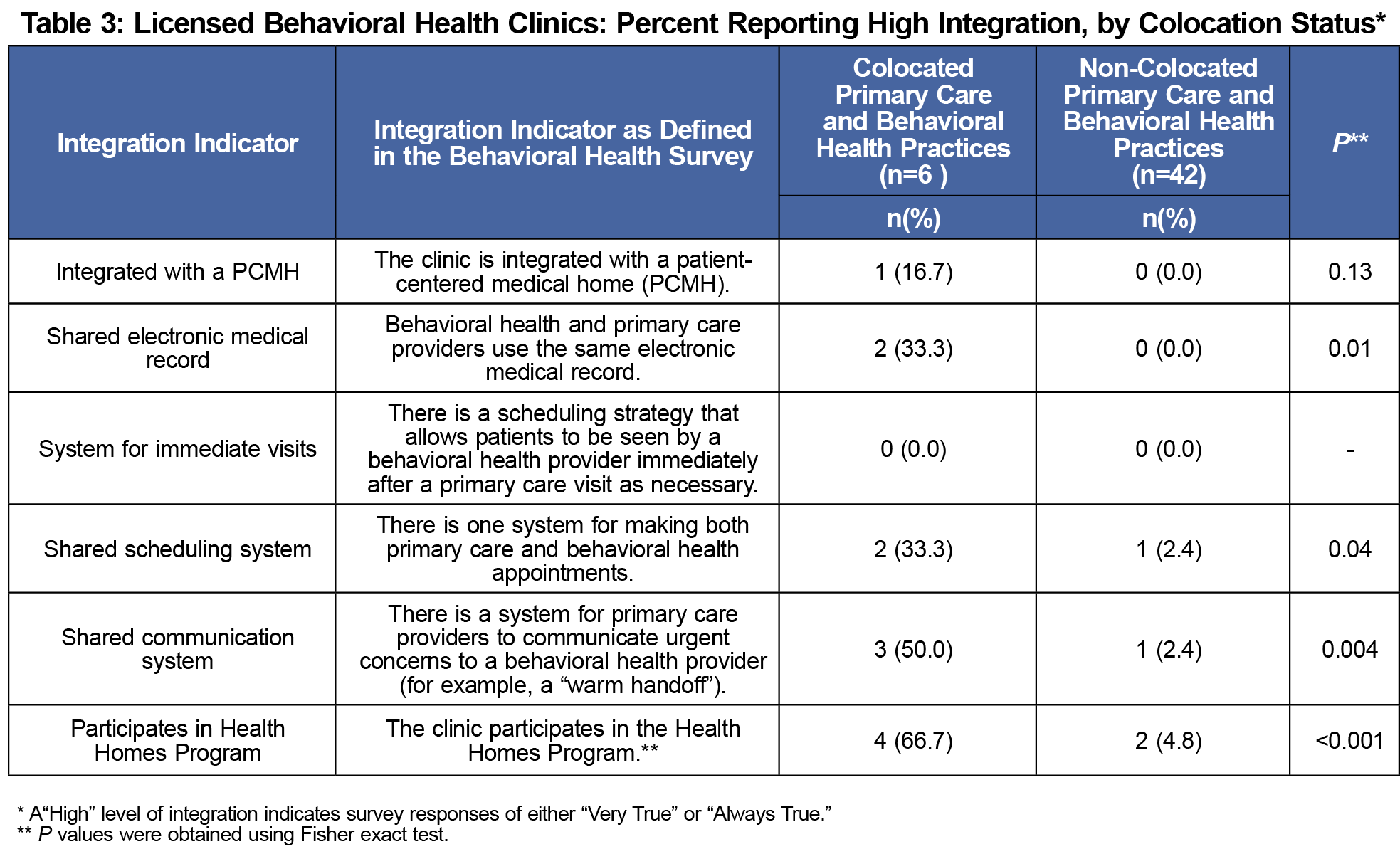

Compared to non-colocated behavioral health clinics, colocated clinics had a greater number of integrated characteristics by most other indicators than did non-colocated clinics, including shared EMRs (33.0% vs 0.0%, P=0.01; Table 3). More colocated than non-colocated clinics reported high integration by shared scheduling systems (33.3% vs 2.4%, P=0.04), and shared communication systems (50.0% vs 2.4%, P=0.004; Table 3).

Rhode Island has limited behavioral health and primary care integration across all three types of behavioral health practices. Nineteen percent, 17%, and 9% of behavioral health clinics, psychology, and psychiatry practices respectively reported some level of integration with primary care practices. Compared to psychology and psychiatry practices, more behavioral health clinics reported high integration across integration indicators.

Colocated behavioral health clinics exhibited higher levels of integration across all other indicators than their non-colocated counterparts. The definition of colocation ranges broadly from separate collaborative practices to fully integrated primary and behavioral clinician teams.7,11 While the exact meaning of colocation was not defined to survey respondents in this study, our findings suggest that colocated practices may be more likely to exhibit other characteristics of integration than non-colocated practices, which agrees with suggestions in prior literature that physical proximity can facilitate further practice integration.11

In this study, higher percentages of Rhode Island behavioral health clinics, compared to psychiatry and psychology practices, report any integration with primary care. Further studies are needed to determine why such differences exist, and to assess which indicators of integration are most important to improving outcomes.3

Although there are proven benefits to practice integration, integration is only happening at a low level in Rhode Island. More practice integration is needed to provide high-quality care to the millions of individuals living with cooccurring behavioral and physical health conditions. The lack of integration that we found calls for a deeper understanding of the barriers to integration, including siloed funding for physical and behavioral health care,19 and solutions to address these barriers, such as alternative payment models.

Limitations

The survey responses were self-reported, categorical, and subjective in nature and thus can be expected to vary in meaning across practices. Additional detail on integration indicators, including colocation or definition of primary care clinicians, was not provided to survey respondents. Variations in response rates between practice types as well as low response rates for psychiatry and psychology practices may also affect the results. These findings may not be generalizable to other states. Additionally, we studied integration from the behavioral health practice perspective instead of from the primary care perspective.3 Although integration may occur in either setting, it is possible that surveying primary care practices may yield different results from those found in this study. Lastly, race/ethnicity data was incompletely collected by study subjects, with 40% of race/ethnicity data unknown, which could hinder service evaluation for vulnerable populations that are already less likely to receive integrated care.8

Behavioral health and primary care integration is beginning to occur in Rhode Island, with a higher degree of integration in licensed behavioral health clinics than in psychology or psychiatry practices, but the overall level of integration remains low. Follow-up studies that track trends in integration, including changes in the number of integrated practices and analysis of which integration indicators are most important to improved physical and behavioral health outcomes, are warranted. We also recommend further study into integration from the primary care practice perspective.

Acknowledgments

This study was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine's 2016 Annual Meeting, May 11, 2016 in Hollywood, FL.

References

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. In: Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2017: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/. Accessed December 6, 2018.

- Ward MC, Miller BF, Marconi VC, Kaslow NJ, Farber EW. The role of behavioral health in optimizing care for complex patients in the primary care setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(3):265-267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3499-8

- Bulter M, Kane R, McAlpine D, et al. Integration of mental health/substance abuse and primary care No. 173 (Prepared by the Minnesota Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-02-0009). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); 2008.

- Petterson S, Miller BF, Payne-Murphy JC, Phillips RL. Mental health treatment in the primary care setting: patterns and pathways. Fam Syst Health. 2014;32(2):157-166. https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000036

- Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2611-2620. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1003955

- Katon W. Collaborative depression care models: from development to dissemination. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(5):550-552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.017

- Peek CJ; National Integration Academy Council. Lexicon for Behavioral Health and Primary Care Integration: Concepts and Definitions Developed by Expert Consensus. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013.

- Wielen LM, Gilchrist EC, Nowels MA, Petterson SM, Rust G, Miller BF. Not near enough: racial and ethnic disparities in access to nearby behavioral health care and primary care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26(3):1032-1047. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2015.0083

- Cohen DJ, Davis M, Balasubramanian BA, et al. Integrating behavioral health and primary care: Consulting, coordinating and collaborating among professionals. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(suppl 1):S21-S31. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2015.S1.150042

- Cohen DJ, Balasubramanian BA, Davis M, et al. Understanding care integration from the ground up: five organizing constructs that shape integrated practices. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(suppl 1):S7-S20. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2015.S1.150050

- Collins C, Hewson D, Munger R, Wade T. Evolving Models of Behavioral Health Integration in Primary Care. New York: Millbank Memorial Fund; 2010. https://www.milbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/EvolvingCare.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2018.

- Kessler R, Miller BF, Kelly M, et al. Mental health, substance abuse, and health behavior services in patient-centered medical homes. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27(5):637-644. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2014.05.140021

- Miller BF, Petterson S, Brown Levey SM, Payne-Murphy JC, Moore M, Bazemore A. Primary care, behavioral health, provider colocation, and rurality. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27(3):367-374. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2014.03.130260

- Long T, Powell S, Dexter M, et al. Rhode Island Department of Health 2015 Statewide Health Inventory Utilization and Capacity Study. 2018. http://www.health.ri.gov/publications/reports/2015HealthInventory.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2018.

- The Rhode Island Department of Health. Rhode Island Behavioral Health Inventory Survey. STFM Resource Library. 2015. https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/rhode-island-behavioral-health-inve?CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a&tab=librarydocuments.

- World Health Organization. Service Availability and Readiness Assessment (SARA): An annual monitoring system for response delivery. 2015. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/systems/sara_introduction/en/.

- Mountainview Consulting Group. Primary Care Behavioral Health-Integration Tool (PCBH-IT). 2008. http://www.massleague.org/Calendar/LeagueEvents/BehavioralHealthConference/Blount-UMassPCBH-IT.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2018.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicaid Health Homes: An Overview. 2015. https://www.medicaid.gov/state-resource-center/medicaid-state-technical-assistance/health-homes-technical-assistance/downloads/hh-overview-fact-sheet-dec-2015.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2018.

- Kathol RG, Butler M, McAlpine DD, Kane RL. Barriers to physical and mental condition integrated service delivery. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(6):511-518. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181e2c4a0

There are no comments for this article.