Introduction: Medical training could not occur without the contributions of patients. Few programs are available that recognize patients for their essential role in medical education, and even fewer explore their impact. The Patients as Teachers (PaT) program was developed to provide an opportunity for medical students to formally honor patients for their contributions and to evaluate their effect on students’ medical education.

Methods: This qualitative study involved the evaluation of transcripts of audiotaped interviews conducted with students and their honorees following participation in the PaT program in 2015 and 2016. Two different sets of authors independently examined transcripts from each year utilizing a descriptive coding strategy. Consensus was reached on theme selection and relationships between themes explored for theory development. A third author ensured grounding of the concepts in the data analyzed.

Results: Four themes emerged: (1) appreciating humanism in medicine, (2) expressing gratitude, (3) connecting patients and students, and (4) experiencing a unique event.

Conclusion: The Patients as Teachers program provides meaningful benefits to both students and patients and has the potential to infuse elements of humanism into medical training.

Patients are central to medical training. They have been teachers regarding their own specific disease processes,1 standardized patients2 and instructors for physical exam skills, patient-centeredness and interprofessionalism.3,4 Students learn from each patient encounter in ways that cannot be replicated in the classroom. These essential contributions are rarely recognized or appreciated.

Many medical schools have a forum for expressing gratitude to cadaver donors and their families.5 Some schools include patient-oriented reflective pieces and personal narratives, patient letters, and thank-you notes within their curriculum.6-8 It is uncommon, however, to directly honor patients for their contributions.9 We initiated a Patients as Teachers (PaT) project at our institution, Tufts University School of Medicine-Maine Medical Center (TUSM-MMC),10 derived from the Legacy Teacher program9 at the University of Missouri School of Medicine. Information about Legacy Teachers was shared by its creator, Dr Betsy Garett, in a 2014 plenary presentation at the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Conference for Medical Student Education. One of the authors in attendance brought the concept back to Maine Medical Center, and a proposal was supported at a departmental and institutional level to pilot a scaled-down version.

Our program is similar to Legacy Teachers in that third-year medical students are encouraged to submit an essay, artwork, or poem nominating for recognition a patient who impacted their training in a meaningful way. Several of the organizers serve as a committee to review deidentified nominations for appropriateness. Upon selection, students and honorees are notified and release forms (media and medical) are obtained. Selected patients and their families are then honored in a celebration. The University of Missouri program has expanded since its inception in 2005 to involve patient nominations by up to 40% of their students and a luncheon that includes hundreds of supporters.9 Our ceremony was conducted on a much smaller scale, providing an informal yet festive forum for the students, honorees and their families to meet and share their stories over brunch. Additional attendees included the students’ preceptors and other physicians involved in the patients’ care, selected faculty and staff, medical student liaisons from upcoming classes, invitees with links to potential funding sources and hospital administrators. The ceremony itself consists of a series of speakers who provide a description of the Maine Track Medical School Program and overview of the Patients as Teachers program, followed by the nominating students’ introduction of their patient selectees and sharing of their nominating essay or artwork. The honorees (or relatives in the case of deceased patients) are invited to speak, contributing a very moving and meaningful part of the program. The honorees have historically spoken eloquently about the impact of the medical students’ involvement in their loved ones’ care. Honorees are provided with a gift and a certificate of appreciation. Other attendees are invited to speak and the official celebration is closed with a final expression of gratitude, followed by time for informal gathering.

We hypothesized that the opportunity to personally reflect on the patient-student relationship and then experience it through the authentic environment of an honoring ceremony would have the capacity to contribute to students’ learning in a personal and more humanistic way than would normally occur. We conducted interviews of participating students and patients after the event in order to explore PaT’s value to medical education and to take the opportunity to improve aspects of the program moving forward.

Design

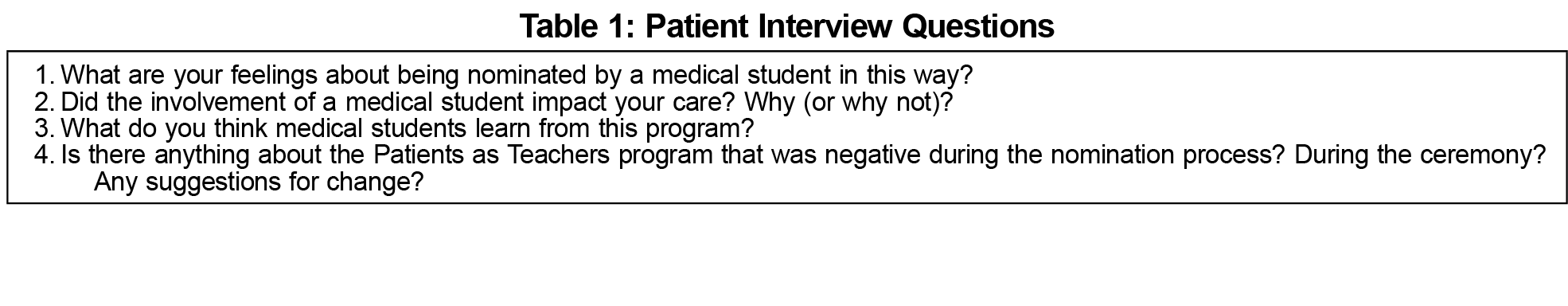

This qualitative study11,12 involved interviews conducted with patients (Table 1) and students (Table 2) in 2015 and 2016. The interview questions were designed by the authors with a humanist theory framework in mind, allowing for the exploration of human behavior through the eyes of the patient.13 Three medical students (n=3 per class, total of 38, 8%) submitted nominations in 2015 and six (n=6 per class, total of 40, 15%) the following year. Nine students and seven patient honorees (or relatives of deceased) were interviewed within 2 weeks of the event by one of the authors (DP) or medical student volunteers. Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed. The Maine Medical Center Institutional Review Board exempted this study from review.

Analysis

Two sets of authors independently examined transcripts (VH and DP, 2015; VH and LM, 2016) through a descriptive coding strategy11 utilizing NVivo10 software. Collaborators discussed codes and emerging themes. Constant comparison14 was utilized to identify emerging themes from both years. In light of the small numbers, the study’s focus on medical education and the emergence of similar overarching themes, the student and patient transcripts were evaluated in combination. Theme consensus was reached and relationships were explored to extract theories. A third author (BBY) ensured grounding of concepts in the data by first independently reviewing the data and subsequently comparing and affirming the appropriateness of the concepts developed by the first two authors.

Four themes emerged: (1) appreciating humanism in medicine, (2) expressing gratitude, (3) connecting patients and students, and (4) experiencing a unique event.

Appreciating Humanism in Medicine

The PaT program served as a reminder of the values that originally attracted students to medicine, such as compassion, empathy, respect, and emotional connections with their patients. The honorees appreciated the acknowledgment of their contributions and the opportunity to leave a legacy.

I think this experience will help remind me of why I went into medicine in the first place. (Student #7)

His medical course taught me many principles of care, but his journey showed me how to navigate them, and his spirit rekindled a love for walking with patients when I needed it most. (Student #1)

I think she [student] learned that the patient isn’t just a patient. They are a human with emotions. That my mom wasn’t just a project. She learned about the emotions involved in a whole realm of things instead of just how do you treat it. (Patient #6)

Expressing Gratitude

PaT provided students with the structure to reflect on their patients’ contributions, a process described as cathartic. Witnessing directly the effects of saying thank-you led to vows to be more grateful going forward. Honorees expressed surprise at the impact they had on their students and appreciation for being recognized.

If I had never thanked him for his participation in my education, I don’t think he’d ever have considered the impact he had in shaping a future physician. (Student #5)

I think that I would be less afraid to say thank you to a patient or to express the impact that they had on me after this experience. (Student #6)

I felt touched and honored…surprised that myself and my story could have any sort of impact to anyone. (Patient #7)

Connecting Patients and Students

Students reflected on the privilege of serving as someone’s doctor and what the physician role meant for them personally. They resolved to adopt behavioral changes: taking more time with patients, self-reflection and appreciating the role of families. The honorees enjoyed sharing the benefits of having a student advocate and the positive impact on their care.

It provided a structured opportunity for reflecting on my experiences with patients rather than focusing on the sheer medical knowledge I acquired from them…I’m a lot less driven by time and efficiency. (Student #2)

…this experience of recognizing the importance and strength of the patient-doctor relationship and celebrating it will be something that helps ground me when I’m struggling. (Student #7)

…the main thing is they have the opportunity to talk to the patient instead of sitting in a large lecture hall. This is much more beneficial to the student than sitting in front of an instructor. (Patient #5)

Experiencing a Unique Event

Students commented on the unique experiential aspects of this program: witnessing first-hand the power of gratitude and the emotional celebration. Patients benefited from connecting with other honorees and hearing their stories. All commented on the novelty and value of PaT and the hope that it would continue.

With PaT, I knew that my words would be shared with the person I was writing about. I was much more reflective and thoughtful. (Student #5)

I decided to participate in PaT because it is a unique event that is unlike other medical school events. (Student #4)

It was very special to see that I wasn’t the only one who had such a great experience with this program. (Patient #5)

This study was viewed through the lens of a humanist theory framework, in which learning is viewed as an intrinsic act garnered through individual experiences13 (such as that exemplified by the PaT program), a principle that can be utilized to incorporate humanistic values into medical education curricula in a variety of settings.15 PaT engages learners in an exploration of the values, autonomy, and culture of patients in an intense and personal way. As concerns are increasingly expressed about medicine evolving into a discipline that focuses more on the disease than the person,16,17 PaT places the patient prominently in the center.

The four themes that emerged (appreciating humanism in medicine, connecting patients and students, expressing gratitude, and experiencing a unique event) identify realms in which the PaT program has the potential to contribute to enhancing humanistic elements in medical student education. Not only do the students benefit from this program, but the patients experience rewards as well through sharing their stories, contributing to medical education, leaving a legacy, and connecting with other patient honorees.

Participation in the second year of the program increased from three students to six, which we considered to be a notable improvement for a class size of forty. Our expectations are that the program and its impact will continue to expand in the years ahead.

Limitations of this study include the involvement of only one site, the small number of participants and the lack of long-term follow-up.

The PaT program provides meaningful benefits to both students and patients and has the potential to infuse elements of humanism into medical training. Hopefully, this program will spread to other institutions, where its value and impact on students and patients can be assessed and celebrated over time.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to recognize the Legacy Teachers program at the University of Missouri School of Medicine for their inspiration. Parts of this paper were presented as a poster at the Maine Medical Center Faculty Development Day, 2015.

References

- Towle A, Brown H, Hofley C, Kerston RP, Lyons H, Walsh C. The expert patient as teacher: an interprofessional Health Mentors programme. Clin Teach. 2014;11(4):301-306.

https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12222.

- McLean M, Johnson P, Sargeant S, Green P. Simulated patients’ perspectives of and perceived role in medical students’ professional identity development. Simul Healthc. 2015;10(2):85-91.

https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0000000000000082.

- Wykurz G, Kelly D. Developing the role of patients as teachers: literature review. BMJ. 2002;325(7368):818-821.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7368.818.

- Cheng PT, Towle A. How patient educators help students to learn: an exploratory study. Med Teach. 2017;39(3):308-314.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1270426.

- Talarico EF Jr. A change in paradigm: giving back identity to donors in the anatomy laboratory. Clin Anat. 2013;26(2):161-172.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.22103.

- Law S. Using narratives to trigger reflection. Clin Teach. 2011;8(3):147-150.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-498X.2011.00446.x.

- Mrduljaš Đujić N, Žitnik E, Pavelin L, et al. Writing letters to patients as an educational tool for medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13(1):114-122.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-13-114.

- White T. Student project thanks the often-unsung teachers of medical school: the patients. Stanford Medicine News Center. May 19, 2014. http://med.stanford.edu/news/all-news/2014/05/student-project-thanks-the-often-unsung-teachers-of-medical-school-the-patients.html. Accessed May 16, 2015.

- University of Missouri School of Medicine. Legacy Teachers. Accessed September 6, 2015.

- Bing-You RG, Bates PW, Epstein SK, Kuhlik AB, Norris SE. Using decentralized medical education to address the workforce needs of a rural state: a partnership between Maine Medical Center and Tufts University School of Medicine. Rural Remote Health. 2010;10(2)1494. https://www.rrh.org.au/journal/article/1494. Accessed January, 2018.

- Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2013.

- O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245-1251.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388.

- Rostami K, Khadjooi K. The implications of behaviorism and humanism theories in medical education. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;3(2):65-70.

- Watling CJ, Lingard L. Grounded theory in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 70. Med Teach. 2012;34(10):850-861.

https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.704439.

- Cohen LG, Sherif YA. Twelve tips on teaching and learning humanism in medical education. Med Teach. 2014;36(8):680-684.

https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.916779.

- Chou CM, Kellom K, Shea JA. Attitudes and habits of highly humanistic physicians. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1252-1258.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000405.

- Birden H, Glass N, Wilson I, Harrison M, Usherwood T, Nass D. Teaching professionalism in medical education: a Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) systematic review. BEME Guide No. 25. Med Teach. 2013;35(7):e1252-e1266.

https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.789132.

There are no comments for this article.