Introduction: Inadequate training of medical students in palliative care has been identified as a barrier to its universal provision. Family medicine physicians frequently provide these services, yet the extent of palliative care training in the family medicine clerkship has been unknown. This study describes the status of palliative care training in the family medicine clerkship, as well as clerkship director perceptions of this training.

Methods: Data were attained through a cross-sectional survey of 141 US and Canadian family medicine clerkship directors administered in fall 2016. Survey items included clerkship director perceived value, interest, and background in palliative care education; presence of educational objectives; hours of training provided; and perceived barriers to palliative care instruction.

Results: Of the clerkship directors who responded (120/141, 81.5%), 31 (25.8%) reported providing no palliative care education and 75 (62.5%) reported palliative care competencies were not specifically assessed. Background in palliative care and explicit educational objectives were associated with more hours of training in palliative care. Clerkship director training in palliative care correlated with value of teaching it in the clerkship.

Conclusion: Palliative care education in the family medicine clerkship is prevalent but a large portion of clerkships do not offer it, and the majority of clerkship directors do not evaluate this learning. Our study found a positive correlation between clerkship director training in palliative care and value placed on palliative training in the family medicine clerkship. Assessing this training in the family medicine clerkship and pursuing additional clerkship director training in the subject could improve the overall quality of education provided.

As an interdisciplinary specialty, palliative care focuses on relieving suffering and maximizing quality of life for patients with serious, life-threatening illness.1 In the next decade, primary care physicians will be expected to play crucial roles in the provision of palliative services. One-third of family medicine physicians completing the 2013 American Board of Family Medicine recertification reported providing palliative care.2

Despite recommendations from the Association of American Medical Colleges endorsing undergraduate medical competencies,3 current educational efforts are inconsistently applied.4 Studies evaluating student palliative care clerkship experiences reveal informal teaching correlates with lower perceived educational value.5,6 Moreover, students’ perceptions of preparedness demonstrate consistent improvement with formal educational experiences.7,8

Formal, structured palliative education in the family medicine clerkship represents an opportunity to teach foundational palliative care skills. However, the current state of palliative care educational practices in family medicine clerkships is unknown. Therefore, the purpose of this national study was to describe palliative education within the family medicine clerkship.

We collected data as part of the 2016 Council of Academic Family Medicine’s (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of family medicine clerkship directors.9,10 The cross-sectional survey is distributed annually to the clerkship directors at the main campus of the school or their designee. Qualifying medical schools are located within the United States and Canada and accredited by either the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) or Committee on Accreditation of Canadian Medical Schools (CACMS). In 2016, 125 unique US and 16 Canadian individuals were identified as family medicine educators directing a family medicine or primary care clerkship. The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board approved this study.

The final survey included questions about the clerkship director, the school, and the clerkship program. Individual-level questions included gender, years practice, years in clerkship role, and training in palliative care. Clerkship questions included medical school class size and length of clerkship. Using Likert scale items, we assessed clerkship director attitudes toward palliative care teaching with two items: the value of its placement in the clinical stage of medical student education, and in the family medicine clerkship. Program questions included presence of stated palliative care-related objectives for the clerkship, total instructional time (hours), assessment methods of palliative care, and barriers to teaching palliative care.

SPSS 2411 software was used for descriptive and associative statistical tests. In associative tests, Spearman ρ correlation was used to test the hypothesized relationship between the ordinal variable of clerkship director training and each of the clerkship director attitude items. Then, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for an association between the presence of stated objectives and (1) attitude toward palliative care placement in the family medicine clerkship, and (2) total instructional hours. Lastly, χ2 was used to test the relationship between presence of stated objectives and palliative care education assessment.

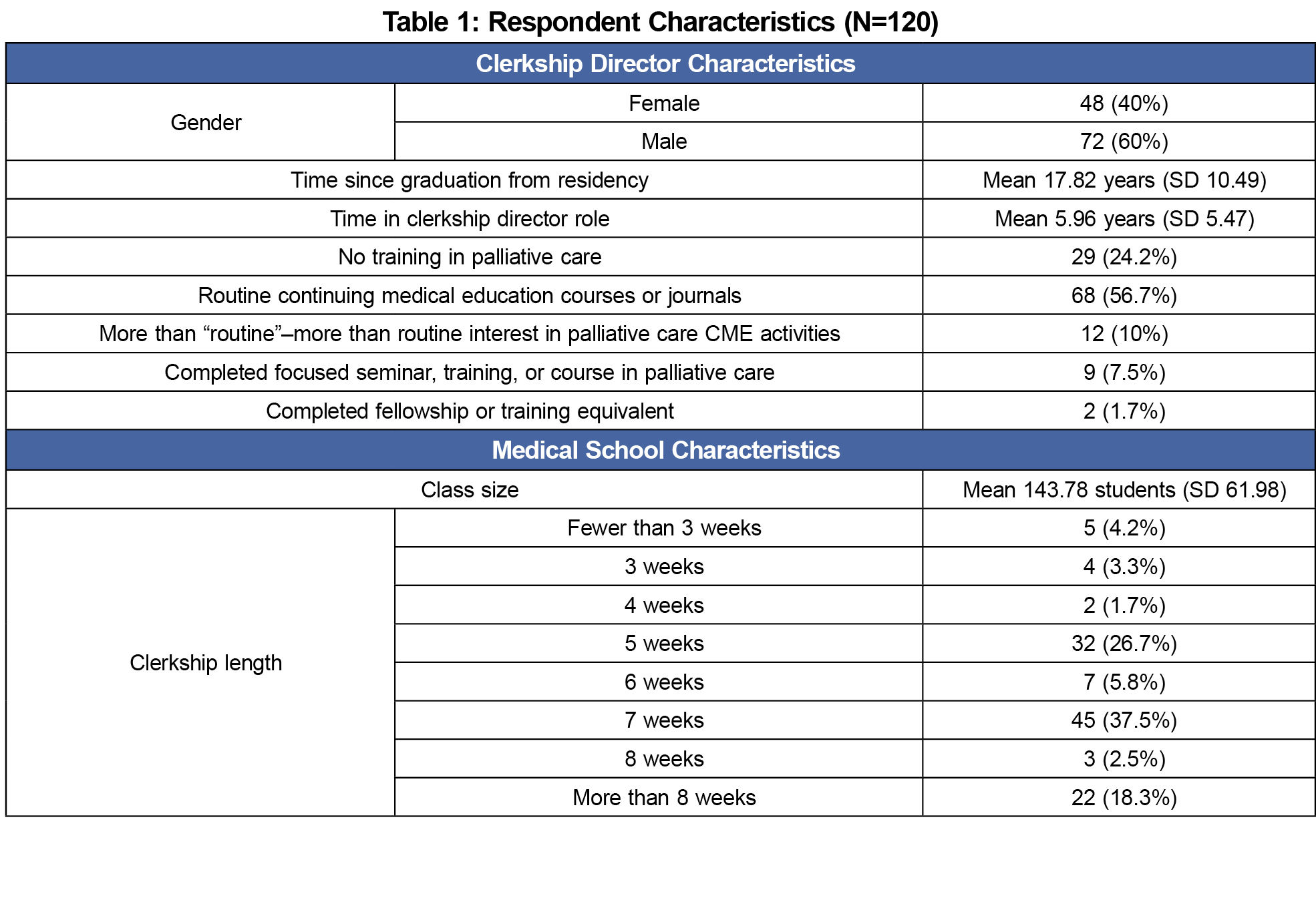

Of the 141 clerkship directors surveyed, 120 (85.1%) responded. Table 1 presents respondent characteristics. Statistical tests demonstrate no significant differences between years practiced or gender and clerkship director training in palliative care. Class size was shown to be unrelated to whether or not the clerkship had stated objectives in palliative care education or whether competencies are assessed. However, class size was negatively correlated with hours of instruction (Pearson R (115)= -.19, P<.05).

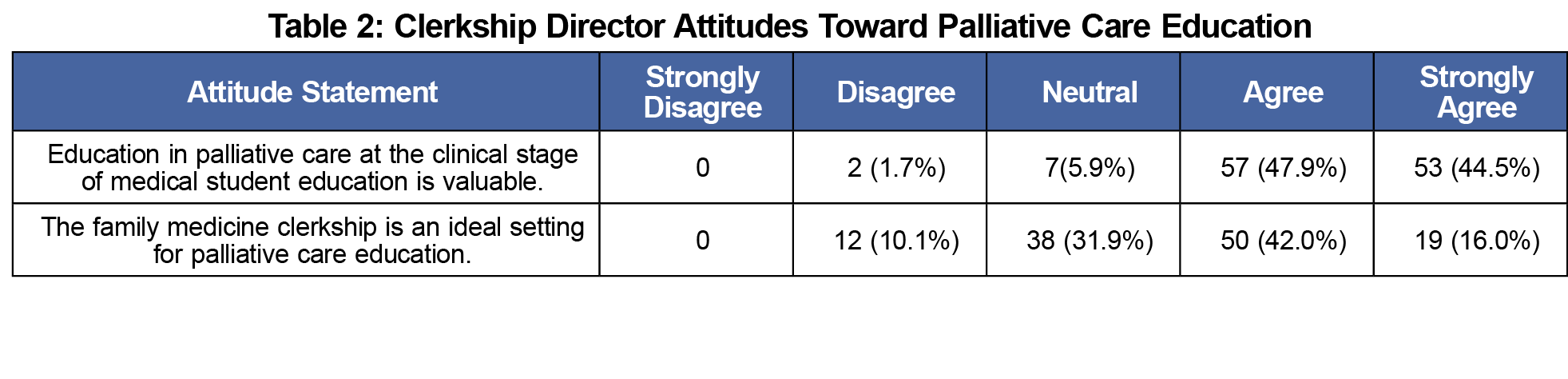

Table 2 presents responses to the attitudinal items. Clerkship director training in palliative care was positively correlated to perceived value in palliative care education (Spearman ρ [119]=0.411, P=0.001) and identification of clerkship as an ideal palliative education setting (Spearman ρ [119]=0.2881, P<.005).

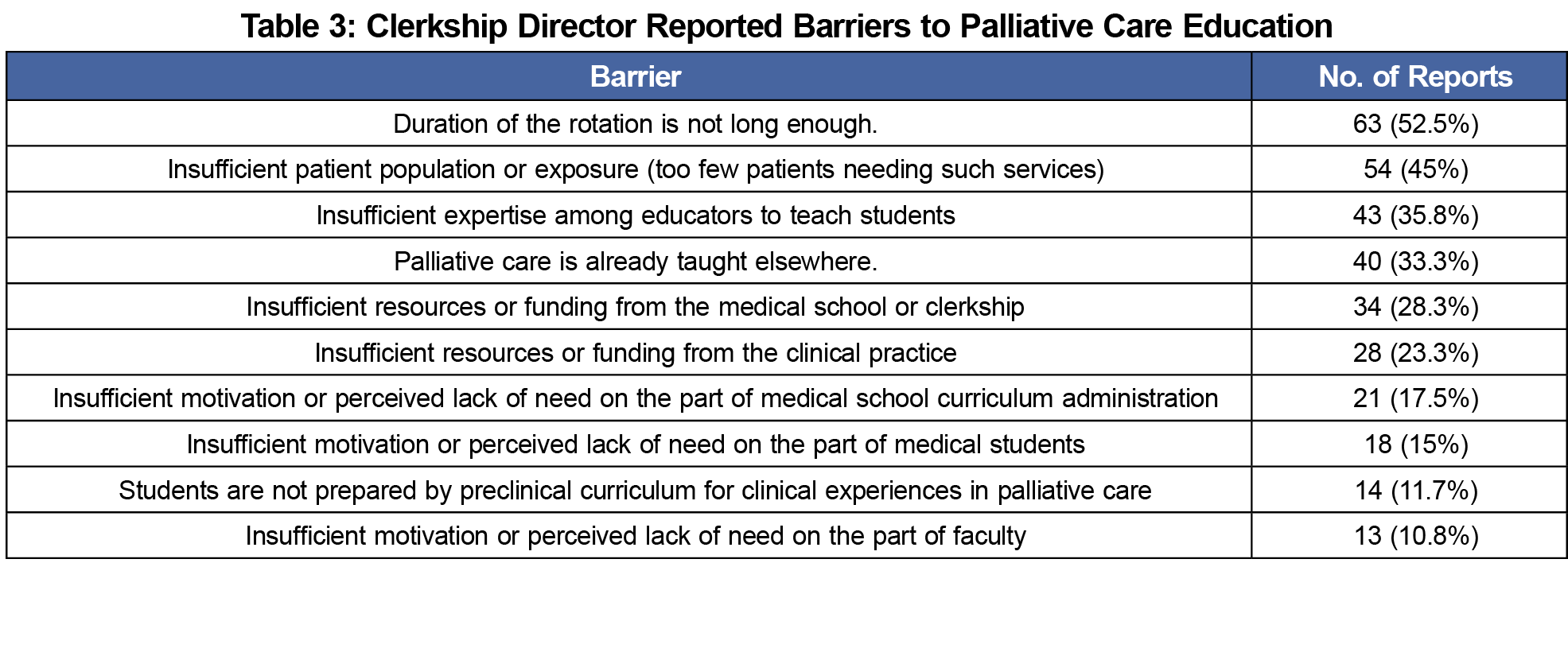

Of the clerkship directors who responded, 41 (34.2%) reported having specific palliative care learning objectives. There was a statistically significant association between the existence of stated objectives and identification of clerkship as the ideal setting to teach palliative care (F [1,117]=13.08, P<.001). Programs with stated objectives reported devoting a significantly greater amount of time to palliative care education (F [1, 114]=24.70, P<.001). Clerkships with stated objectives were significantly more likely to assess student learning (χ2 [1, 111]=21.69, P<.001). A large majority of clerkship directors (75, 62.5%) reported not specifically evaluating or assessing palliative care competencies. Finally, 31 (25.8%) reported no structured education or training in palliative care during the family medicine clerkship. Table 3 presents barriers perceived by clerkship directors.

As medical schools continue to respond to the increased demand for education in palliative care competencies, current opportunities in the family medicine clerkship are being missed. Palliative care education in the family medicine clerkship is prevalent, but our study reveals a large portion of clerkships do not offer any specific training in this field. Even when this education is provided, the majority of clerkships lack evaluation of this learning. Assessing situations where palliative care teaching is occurring would help to identify and improve teaching opportunities in family medicine or other clerkships. Further research on validated assessment tools that predict future palliative care competency are needed.

Our study also showed a positive correlation between clerkship director training in palliative care and the value they placed on palliative training in the family medicine clerkship. Thus, pursuit of clerkship director educational opportunities in palliative medicine could support palliative education in the family medicine clerkship. Providing primary palliative care education to all medical students could improve patient accessibility in palliative care across the medical field from rural family physicians to subspecialty surgery.

The most frequently cited barriers to palliative education situated within the family medicine clerkship were lack of time and patient exposure on the clerkship. This replicates previous research that shows lack of time on the overall clerkship as well as faculty devoted time as constraints to palliative education on internal medicine clerkships.12 Efforts to address limited time may include exploration of efficiency through interclerkship palliative teaching. Palliative care is commonly taught elsewhere in the medical school curriculum,13 such as the internal medicine clerkship14 or a longitudinal palliative care curriculum.15 Construction of a longitudinal, interdisciplinary palliative care curriculum across the 4 years of medical school should be the goal.16 This could help to address the lack of exposure to patients needing palliative care as well.

Limitations of this study include the cross-sectional and descriptive nature of the survey, and respondent self-selection. Also, data were derived from a self-reported survey, which can be susceptible to bias. Although this survey attempted to assess the methods and nature of education, it was limited to the response of clerkship directors, and surveys of learners may be valuable. Additional research is needed to validate the most efficient and enduring educational methods and competency assessments to provide quality palliative care.

Clerkship director training in palliative care, the presence of explicitly stated objectives, and assessing the education provided may increase the time and quality of palliative care education. This study reveals palliative care teaching opportunities on the family medicine clerkship, which through development would provide quality educational opportunities supporting all medical students and their most challenging patients. Addressing the suffering of patients and their families is vital and must be championed to educate future doctors early in their careers.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Council of Academic Family Medicine Staff for their assistance in survey administration and data collection.

Presentations: This study was presented at the 2018 STFM Annual Spring Conference, May 5-9, Washington, DC.

Disclaimers: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the US Air Force, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences or the Department of Defense.

References

- Frist WH, Presley MK. Training the next generation of doctors in palliative care is the key to the new era of value-based care. Acad Med. 2015;90(3):268-271. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000625

- Ankuda CK, Jetty A, Bazemore A, Petterson S. Provision of palliative care services by family physicians is common. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(2):255-257. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2017.02.160230

- AAMC Task Force on the Preclerkship Clinical Skills Education of Medical Students. Recommendations for Clinical Skills Curricula For Undergraduate Medical Education. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2008. https://www.aamc.org/download/130608/data/clinicalskills_oct09.qxd.pdf.pdf Accessed May 1, 2017.

- Horowitz R, Gramling R, Quill T. Palliative care education in U.S. medical schools. Med Educ. 2014;48(1):59-66. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12292

- Ratanawongsa N, Teherani A, Hauer KE. Third-year medical students’ experiences with dying patients during the internal medicine clerkship: a qualitative study of the informal curriculum. Acad Med. 2005;80(7):641-647. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200507000-00006

- Rabow M, Gargani J, Cooke M. Do as I say: curricular discordance in medical school end-of-life care education. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(3):759-769. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2006.0190

- Fraser HC, Kutner JS, Pfeifer MP. Senior medical students’ perceptions of the adequacy of education on end-of-life issues. J Palliat Med. 2001;4(3):337-343. https://doi.org/10.1089/109662101753123959

- Billings ME, Engelberg R, Curtis JR, Block S, Sullivan AM. Determinants of medical students’ perceived preparation to perform end-of-life care, quality of end-of-life care education, and attitudes toward end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(3):319-326. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2009.0293

- Mainous AG III, Seehusen D, Shokar N. CAFM Educational Research Alliance (CERA) 2011 Residency Director survey: background, methods, and respondent characteristics. Fam Med. 2012;44(10):691-693.

- Shokar N, Bergus G, Bazemore A, et al. Calling all scholars to the council of academic family medicine educational research alliance (CERA). Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(4):372-373. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1283

- Bryant A, Blake-Lamb T, Hatoum I, Kotelchuck M. Women’s use of health care in the first 2 years postpartum: occurrence and correlates. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(S1)(suppl 1):81-91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2168-9

- Shaheen AW, Denton GD, Stratton TD, Hoellein AR, Chretien KC. End-of-life and palliative care curricula in internal medicine clerkships: a report on the presence, value, and design of curricula as rated by clerkship directors. Acad Med. 2014;89(8):1168-1173. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000311

- Chiu N, Cheon P, Lutz S, et al. Inadequacy of palliative training in the medical school curriculum. J Cancer Educ. 2015;30(4):749-753.

- Hoffman LA, Mehta R, Vu TR, Frankel RM. Experiences of female and male medical students with death, dying, and palliative care: One Size Does Not Fit All. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(6):852-857. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909117748616

- Denney-Koelsch EM, Horowitz R, Quill T, Baldwin CD. An integrated, developmental four-year medical school curriculum in palliative care: a longitudinal content evaluation based on national competency standards. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(9):1221-1233. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2017.0371

- Head BA, Schapmire TJ, Earnshaw L, et al. Improving medical graduates’ training in palliative care: advancing education and practice. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2016;7:99-113. https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S94550

There are no comments for this article.