Background and Objectives: Caring for geriatrics and palliative care patients requires integrated interprofessional care. Studies regarding interprofessional education in family medicine reveal concerns by residents regarding applicability in future practice. Our study objective was to determine the effectiveness of teaching multispecialty geriatric and palliative care skills to family medicine residents using an interprofessional clinic curriculum.

Methods: We evaluated an interprofessional geriatric and palliative care outpatient curriculum from March 2014 to June 2015. The interprofessional team included pharmacists, psychologists, family medicine geriatricians, and palliative care providers. Family medicine residents in a 3-year residency program completed pre- and postassessments evaluating their confidence and knowledge in specific areas of geriatric and palliative care. These assessments covered their abilities in starting advance care planning and setting goals in care discussions, as well as fall and depression assessment and elderly medication review. The subsequent resident perception of teaching effectiveness was also assessed. Qualitative comments were evaluated for themes. Patient perceptions were also surveyed.

Results: Family medicine residents completed 52 surveys (51%). Improvements in all areas were significant (P<0.05). Postevaluation mean scores by year and by session demonstrated significant improvements in palliative care tools and teaching effectiveness. Qualitative comments revealed three themes: overall positive or negative educational value and understanding of assessments, reflection on interprofessional collaboration and team experience value, and improvements in logistics and collaboration. Patient satisfaction surveys reported improved satisfaction with their PCMH.

Conclusions: The use of an interprofessional and multispecialty clinic curriculum to teach geriatric and palliative care improved resident self-assessed knowledge and confidence as well as teaching effectiveness. Further studies evaluating resident exposure to such visits could substantiate the long-term influence of this educational endeavor.

Family physicians increasingly lead and participate in integrated professional teams.1-3 Family medicine milestones endorse “Role model[ing] leadership, integration, and optimization of care teams” by residents (Systems-Based Practice-4).4 Residents with interprofessional training report better communication and collaboration, and some residencies incorporate such learning experiences.5-7 However, some residents doubt the educational value and applicability of this type of teamwork for future practice.1-3,5,6

Family medicine residencies may provide ideal situations for interprofessional, multispecialty education. Family medicine residencies often train residents in parallel with teaching programs for pharmacists, psychologists, and specialty fellowships such as those in geriatrics and palliative care.6-9 In no area of family medicine is interprofessional care more important than in geriatrics and palliative care, where complicated diseases and medical regimens, end-of-life care, and a limited specialty workforce require the combined resources of a variety of providers.10-13

We evaluated a model of interprofessional education that colocated a multispecialty geriatrics and palliative care clinic in a residency patient-centered medical home (PCMH). Our goals for this experience included resident education in geriatrics and palliative care skills, as well as developing teaching effectiveness to promote confidence in leading future practice teams.

Residents from the Alaska Family Medicine Residency Clinic (AKFMR) participated in this curricular clinic (half day of didactics, patient discussion, and a clinic visit) during their longitudinal and postgraduate year (PGY) 3 geriatric block rotation. During their yearly program evaluation, previous residents had requested a specialty clinic experience to enhance geriatric teaching. Authors evaluated this curricular clinic from March 2014 through December 2015. The University of Alaska Anchorage Institutional Review Board exempted this clinic and curriculum from review.

The AKFMR program (3 years, 12 residents per year) focuses on preparing residents to practice in underserved Alaskan communities.

Curricular Clinic Development

The faculty team met three times to review literature, determine focus areas and learning objectives, and develop evaluations.14 The team included family medicine faculty physicians with a Certificate of Added Qualifications in palliative care or geriatrics, as well as a psychologist, pharmacist, home-visiting physician assistant, and a palliative care fellow. Focus areas included depression screening, falls assessment, symptom appraisal, and advance care planning (ACP).

Curricular Clinic Preparation

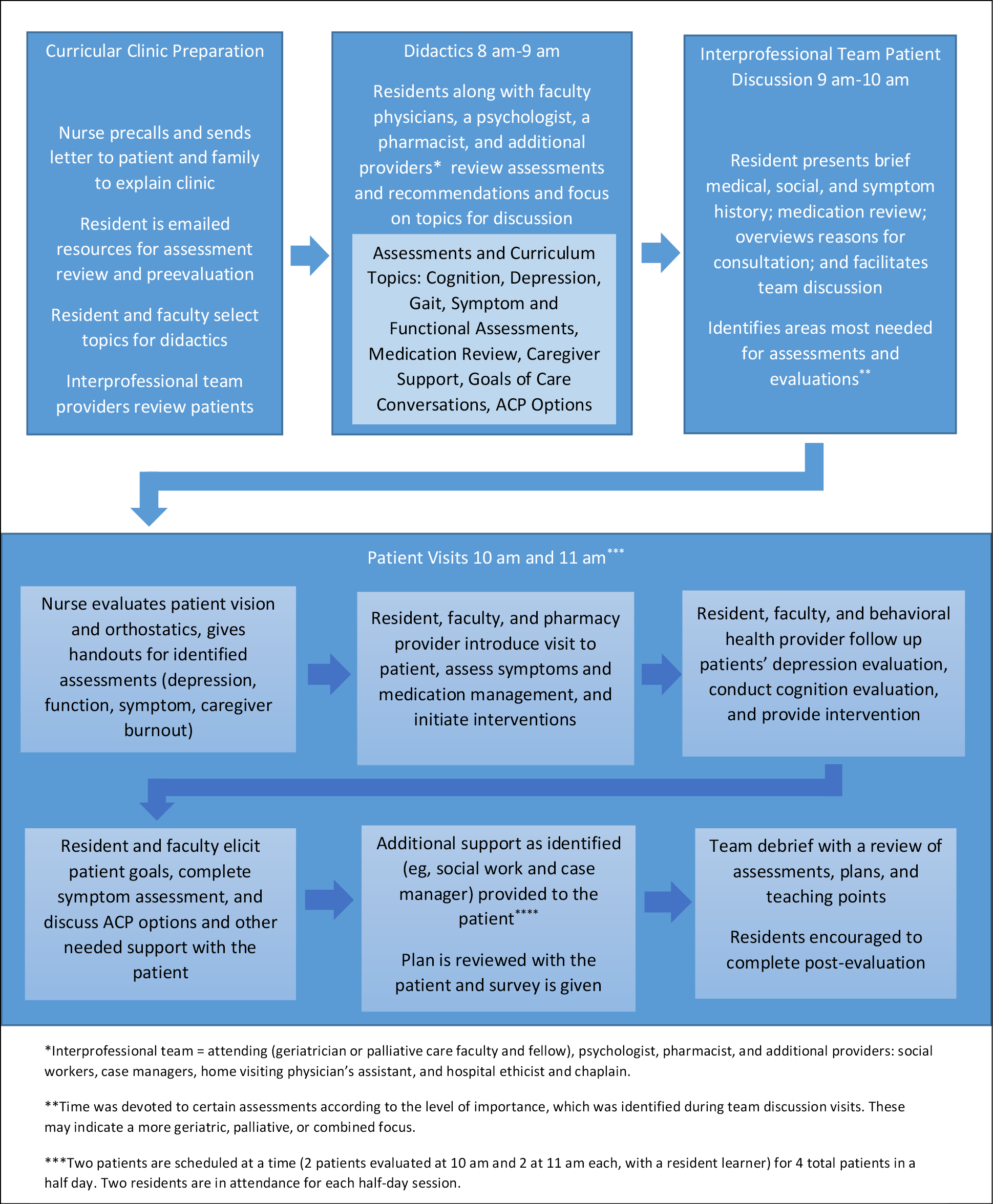

Residents and faculty referred their complicated geriatric and palliative care patients to the clinic. Nurses contacted the patients and caregivers prior to the clinic to explain the goals and assessments of the clinic. The faculty team and residents were emailed with information on the patients and assessments for review.

Curricular Clinic

On the curricular clinic morning, the faculty team and residents reviewed focus areas and assessments in a didactic session (8 am-9 am). Residents participated initially as learners, then progressed to teaching the assessments to newer residents and students in later sessions.

Residents presented a patient review (9 am-10 am). The team then discussed issues related to the didactic focus areas. Lastly, additional care team members (eg, ethicists, chaplains, social workers) identified other information based on the discussion.

Patient visits (10 am and 11 am) began with a nurse assessing vision and orthostatics while the residents and faculty team huddled to review key assessments. The residents interviewed, examined, and completed assessments with patients and an attending (geriatric or palliative care faculty or fellow) and a rotating pharmacist and psychologist. Additional providers, such as social workers, provided support as needed. The faculty team initially mentored residents during their patient assessments. Residents progressed in later sessions to independent interactions with supervision (Figure 1).

Evaluation and Data Review

Investigators developed an anonymous resident pre- and postevaluation and patient survey. The resident introductory email included instructions on completing the evaluations, and evaluations were provided prior to didactics and then following clinics. The assessments included a knowledge and confidence self-assessment (both on a 4-point Likert scale) and qualitative comments on experience. After the clinic was implemented, a patient survey queried satisfaction (4-point Likert scale). Patients received the survey at the beginning of the visit with instructions to complete it after the visit.

Statistical Analysis

Investigators attained pre- and postevaluation means and analyzed them with a tailed t-test (significance P<0.05). Posttest scores were further compared per postgraduate year and number of sessions attended (1-4) using one-way ANOVA and Tukey post-hoc analyses (SPSS).

The authors and a nonauthor faculty analyzed qualitative comments through a standard thematic technique (MAXDQA software, Berlin, Germany: Verbi GmbH; 2017).15 Authors J.K.M. and L.A. met regularly to review responses, establish codes and coding frameworks, and identify and define themes and subthemes. Author A.D. reviewed the coding framework and themes. Authors J.K.M., L.A, and a nonauthor faculty then achieved consensus for the analysis as well as thematic saturation. Question prompts in the evaluations included reflection on learning points of the experience, as well as feedback on flow, content, didactics, patient interactions, or other parts of the experience. Patient survey means were calculated.

One hundred and one evaluations were distributed, and 52 were completed (51.4%). Response numbers by session attendance and per PGY included first-session evaluations by PGY-1 (9), PGY-2 (10), and PGY-3 (4); second session evaluations by PGY-2 (5) and PGY-3 (10); third session evaluations by PGY-3 (9); and fourth session evaluations by PGY-3 (3).

Evaluations demonstrated significant perceived improvement (P<0.05) in the focus areas; (Table 1). ANOVA postevaluation means by numbers of sessions attended demonstrated numerically higher scores in perceived knowledge of palliative care (F(3,47)=3.00, P=0.04) and ACP (F(3,48)=4.19, P=0.01), as well as confidence in teaching effectiveness (F(3,48)=2.954, P=0.042). Post-hoc analysis revealed that the mean score in knowledge of ACP after one session was 2.78 (SD 0.52), which was significantly different from the third session’s mean score of 3.45 (SD 0.33, P=0.01). ANOVA postevaluation scores by PGY in these areas revealed numerically higher means in perceived knowledge of palliative care (F(2,48)=5.32, P=0.01) with a post-hoc mean for PGY-1 of 2.78 (SD 0.44), which was significantly different from that for PGY-3 (3.37, SD 0.51, P=0.01). Knowledge of ACP in PGY-1 (F(2,49)=7.88, P=0.00) had a post-hoc mean of 2.33 (SD 0.50), which was significantly different from that for PGY-2 (3.07, SD 0.26, P=.0.01) and PGY-3 (3.14, SD 0.65, P=0.00). Additionally, confidence in teaching effectiveness in PGY-1 (F(2,49)=7.071, P=0.002) had a post-hoc mean of 2.00 (SD 0.87), which was significantly different from that for PGY-3 (2.96, SD 0.64, P=0.03).

Qualitative responses revealed nine codes and three themes (N=86, average 14.5 words per response). The themes identified revolved around the educational value of the clinic, the benefits of collaboration, and the suggested areas of improvement (Table 2).

Patient survey responses (32% response rate, 52/162) reported improved PCMH satisfaction (mean 3.58) and sense of support (mean 3.63, Table 3).

Our curriculum provides an innovative model for colocating an interprofessional geriatric and palliative care clinic in a residency PCMH. Qualitative comments corroborate past resident studies regarding improved collaborative appreciation and were used to identify specific learned skills and to make suggestions for improvement. Residents perceived improved skills in depression, fall risk, and symptom assessment. Residents also reported improvement by number of sessions attended and PGY in palliative care skills and future teaching effectiveness. Our patients reported improved PCMH satisfaction and perceived support.

Limitations of this study include the lack of a control group (single site), follow up on qualitative comments, and repeated evaluation to assess durable effects. Furthermore, each educational method and interprofessional learner lacked separate evaluations. Residents did not perceive a significant improvement in scores by number of sessions attended, and PGY scores may demonstrate the effects of overall progression through residency as opposed to learning solely from this clinic. Low response numbers may reflect a response bias and the optional nature of the evaluation. Patient survey limitations include potential response bias and lack of presurvey and durable effect surveys.

In conclusion, colocating a specialty interprofessional geriatrics and palliative care clinic within a residency PCMH may enable resident skill growth and teaching effectiveness to improve future practice teams. Future research could further explore the impact of this clinic on resident development.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the additional team members who started this curricular clinic: Dr Stephen Rust, Dr Anne Musser, Shannon Fowler, Robin Cooke, Kathryn Butler, Judith Renwick, Sarah Dewane, and Dr Harold Johnston.

Presentations: Collaboration of Mental Health and Pharmacy in Family Medicine Geriatrics and Palliative Care Curriculum Visit (breakfast discussion). STFM Conference on Practice Improvement, November 29-December 3, 2017, Louisville, KY.

References

- Barker KK, Oandasan I. Interprofessional care review with medical residents: lessons learned, tensions aired—a pilot study. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(3):207-214. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820500138693

- Coleman MT, Roberts K, Wulff D, van Zyl R, Newton K. Interprofessional ambulatory primary care practice-based educational program. J Interprof Care. 2008;22(1):69-84. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820701714763

- Soones TN, O’Brien BC, Julian KA. Internal Medicine Residents’ Perceptions of Team-Based Care and its Educational Value in the Continuity Clinic: A Qualitative Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(9):1279-1285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3228-3

- Boland D, Scott M, Kim H, White T, Adams E. Interprofessional immersion: use of interprofessional education collaborative competencies in side-by-side training of family medicine, pharmacy, nursing, and counselling psychology trainees. J Inter Prof Care. 2016. 30:6, 739-746. https://10/1080/13561820/2016.1227963.

- Lounsbery JL, Moon J, Prasad S. Assessing collaboration between family medicine residents and pharmacy residents during an interprofessional paired visit. Fam Med. 2015;47(5):397-400.

- Porcerelli JH, Fowler SL, Murdoch W, Markova T, Kimbrough C. Training family medicine residents to practice collaboratively with psychology trainees. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2013;45(4):357-365. https://doi.org/10.2190/PM.45.4.f

- Lounsbery JL, Jarrett JB, Dickerson LM, Wilson SA. Integration of clinical pharmacists in family medicine residency programs. Fam Med. 2017;49(6):430-436.

- Bragg EJ, Warshaw GA, Meganathan K, Brewer DE. National survey of geriatric medicine fellowship programs: comparing findings in 2006/07 and 2001/02 from the American Geriatrics Society and Association of Directors of Geriatric Academic Programs Geriatrics Workforce Policy Studies Center. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(11):2166-2172. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03126.x

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Advanced Search Hospice and Palliative Medicine Fellowships. https://apps.acgme.org/ads/Public/Programs/Search?stateId=&specialtyId=153. Accessed December 27, 2017.

- Mion L, Odegard PS, Resnick B, Segal-Galan F. Geriatrics Interdisciplinary Advisory Group, American Geriatrics Society. Interdisciplinary care for older adults with complex needs: American Geriatrics Society position statement. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006. May:54(5):849-52.

- National Consensus Project for Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, Third Edition. 2013. https://www.hpna.org/multimedia/NCP_Clinical_Practice_Guidelines_3rd_Edition.pdf Accessed 1/10/2017.

- Lupu D. Estimate of Current Hospice and Palliative Medicine Physician Workforce Shortage. American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine Workforce Task Force. Med 2017. Jun:49(6):430-436.

- Olivaro M. Doctor shortage: who will take care of the elderly? US News World Rep. 2015;21(April). https://health.usnews.com/health-news/patient-advice/articles/2015/04/21/doctor-shortage-who-will-take-care-of-the-elderly. Accessed November 21, 2017.

- Kam J. Teaching tools by competencies; interprofessional curriculum in geriatrics and palliative care. 2017. STFM Resource Library. http://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/resourcelibrary/ourlibrary/viewdocument?DocumentKey=30f9f714-39a4-4269-bb62-4f32e9b3e247. Accessed October 2, 2018,

- Patton, M. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Los Angeles: Sage Publications; 2002.

There are no comments for this article.