Introduction: Despite the increasing popularity of longitudinal primary care experiences in North America and beyond, there is a paucity of work assessing these medical undergraduate experiences using reliable and valid questionnaires. Our objective in this study was to evaluate a new preclerkship longitudinal family medicine experience (LFME) course at McGill University by assessing family physician preceptors’ self-reported ratings of the perceived effects of this course, and to compare their responses with ratings provided by medical students who completed the course.

Methods: This study is part of a larger evaluative research project assessing the first edition of the LFME. Students (N=187) and preceptors (N=173) of the 2013-2014 cohort were invited to complete separate online questionnaires in the spring through summer of 2014. The preceptor survey contained 53 items, 14 of which were nearly identical to items in the student survey (published elsewhere) and served as the basis for comparing preceptor and student ratings of the LFME.

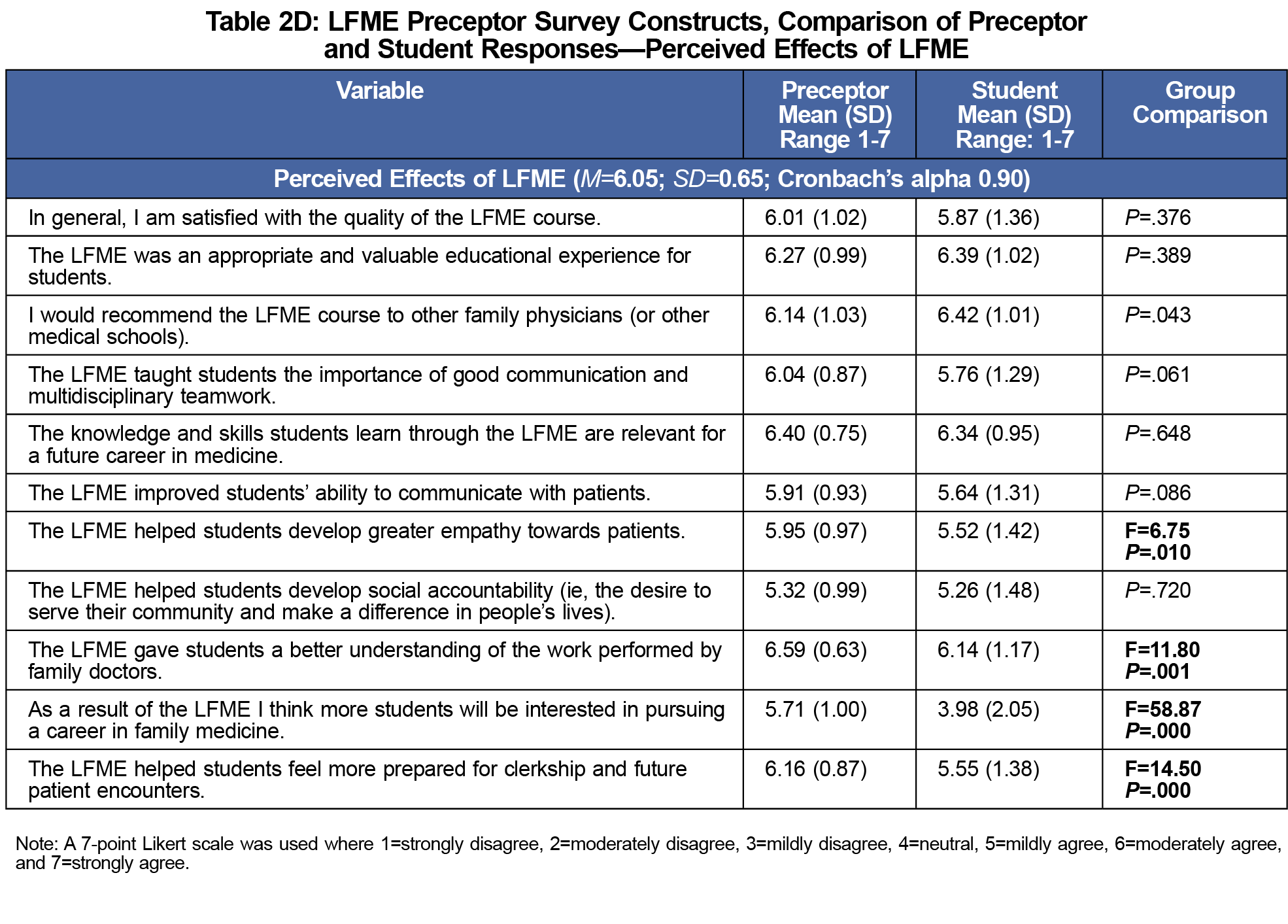

Results: Ninety-nine preceptors (57% response rate; 55% female) and 120 students (64% response rate; 58% female) completed the surveys. Preceptors and students did not significantly differ in their overall ratings of the course, as both groups were satisfied with the quality of the LFME and felt it was an appropriate and valuable educational experience. However, preceptors had more positive ratings regarding their role and the benefits of the course than did medical students.

Conclusion: This study corroborates prior work showing extensive perceived benefits of longitudinal preclerkship exposure to primary care; however, preceptors were found to report more positive reviews of the course than students. This study also provides new innovative tools to assess students’ and preceptors’ perceptions of longitudinal, preclerkship family medicine courses available for use over time and in different educational contexts.

In response to societal demands for more family physicians, numerous medical schools in the United States, Canada, and beyond have implemented longitudinal, community-based, preclerkship or integrated clerkship experiences in their curricula.1-5 Early clinical exposure in primary care settings has many documented benefits, including preceptor role modelling, enhancement of students’ knowledge, affective learning, development of clinical skills, professional socialization, and improved attitudes toward primary care.6-10 However, there are few tools that measure the perceived effects of these educational innovations by their main stakeholders (ie, medical students and physician preceptors) in a valid and reliable way. In order to fulfill this research need, we focused on the first edition of McGill University’s Longitudinal Family Medicine Experience (LFME) course, which launched in August 2013.

The LFME is an innovative educational initiative where first-year medical students attend their preceptors’ clinical practices about twice per month for a total of 20 half days throughout the first year of medical school. These sessions may take place in any clinical context in which the preceptor operates, such as private clinics, community health care centers, family medicine groups, emergency rooms, and nursing homes. The ultimate goals of the course are to give students early exposure to the practice of family medicine, and earlier opportunities to practice history taking, communication, and physical examination skills. As part of a larger evaluative research project, we created surveys to address the following overarching research question: What are the perceived effects of the LFME course from the 2013-2014 cohort of students and preceptors? The results of the questionnaire completed by students have been published elsewhere.11 In this study we report preceptors’ views, and compare similar items across both questionnaires.

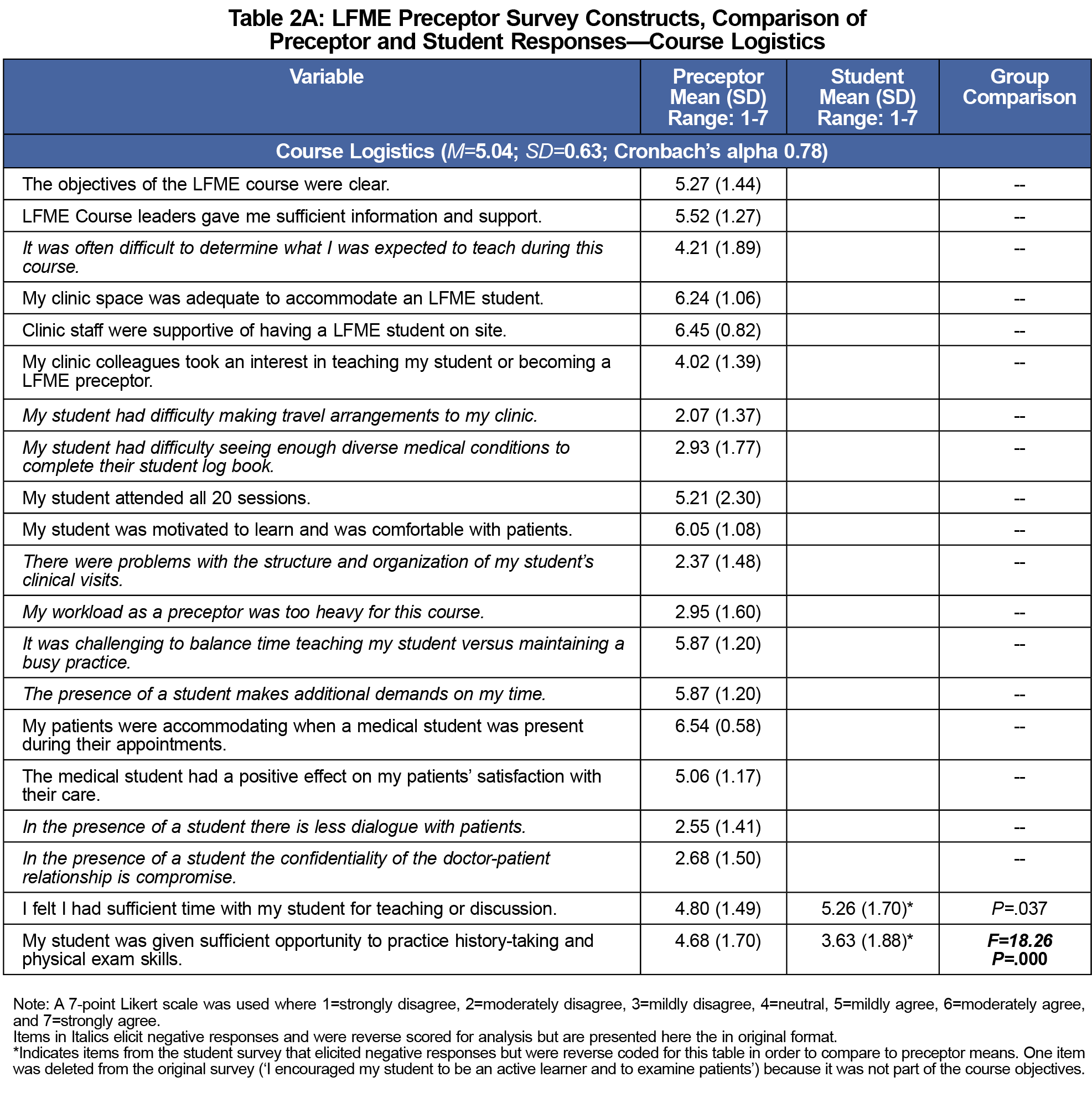

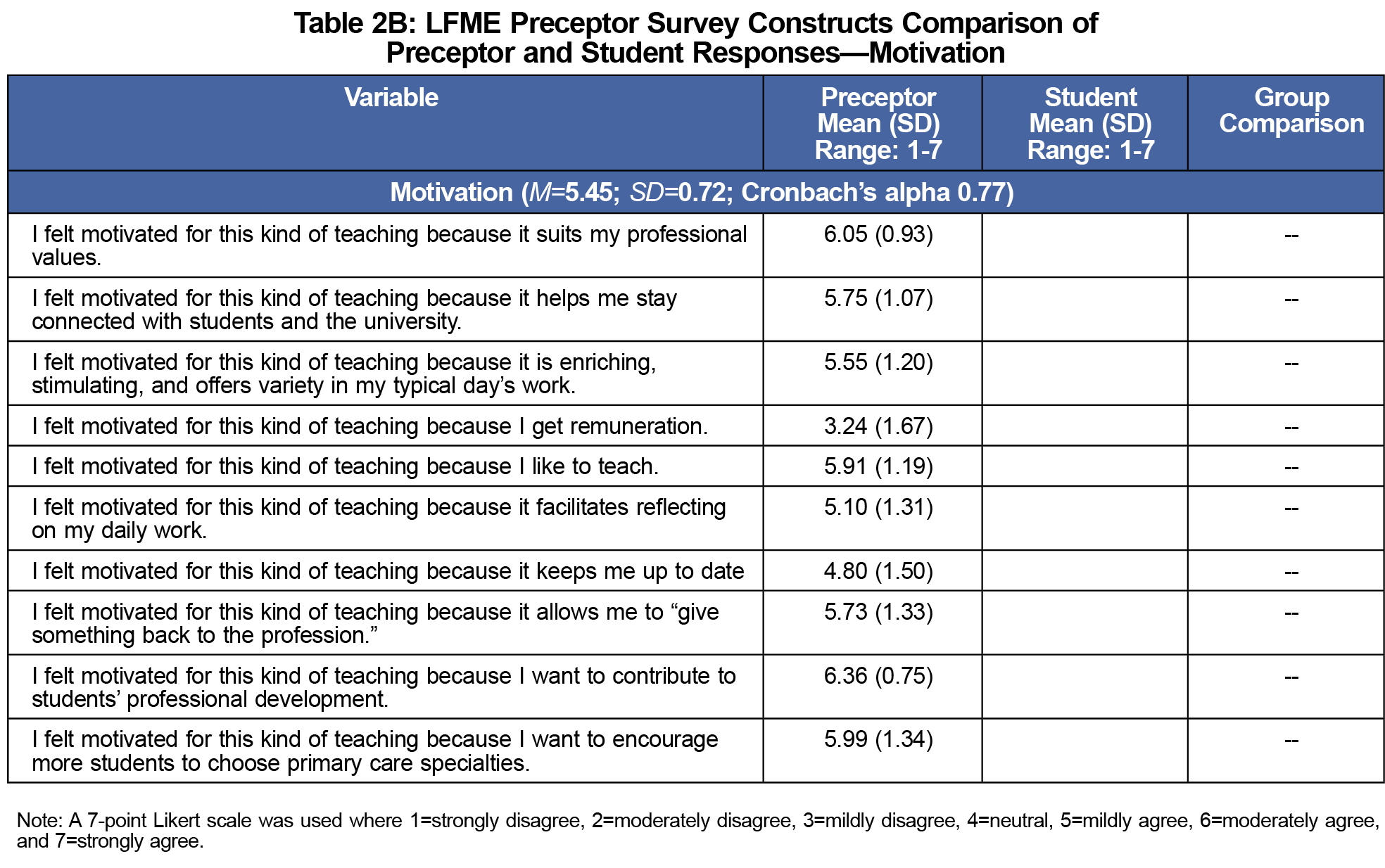

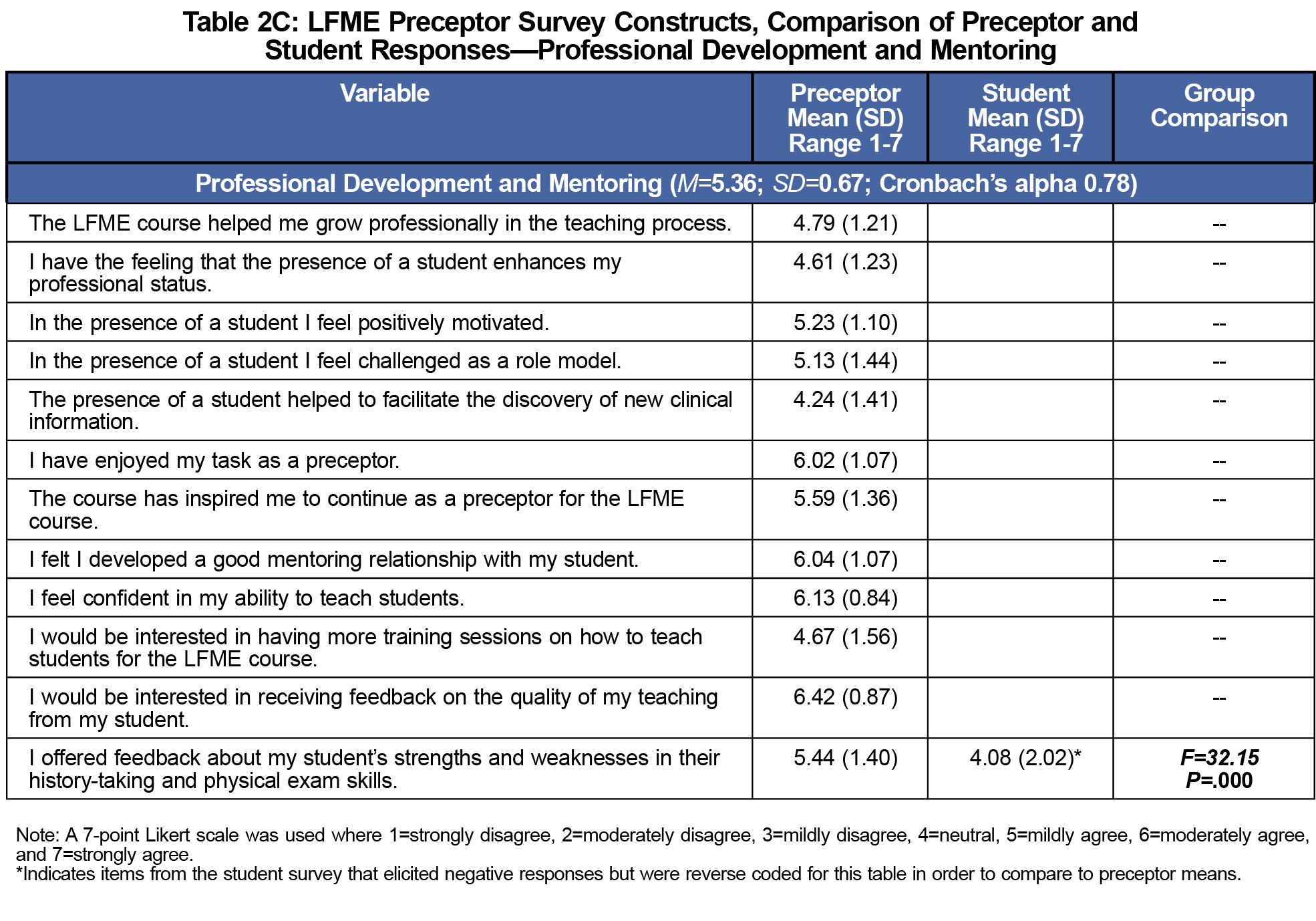

All 187 first-year medical students and 173 LFME preceptors were invited to complete online questionnaires via fluidsurveys.com in the spring through summer of 2014. We first drafted the student version of the LFME survey based on an extensive literature review and alignment with the objectives of the course; its final version included 31 items and the results are published elsewhere (copies are available upon request).11 The preceptor version of the LFME survey was created afterwards using a 7-point Likert scale (eg, 1=strongly disagree, 7=strongly agree). It included 53 items that aimed to measure the following constructs: course logistics, motivation for becoming an LFME preceptor, professional development and mentoring, and perceived benefits of the LFME. Fourteen of the items were nearly identical to the student version of the LFME survey (see Tables 2A-D); 29 items were adapted from previous surveys;12-14 and the remaining 10 items were created to further evaluate the constructs listed above (eg, course logistics), based on consensus from a group of medical education researchers at McGill University. Demographic items assessed standard demographic characteristics (eg, age, sex of preceptor and student, years of teaching experience), as well as unique characteristics specific to our group of preceptors and geographic location (eg, location of clinic, and type of patient exposure).

SPSS 21.0 was used for data analysis. Some missing data occurred randomly because a few participants missed a single item, while nine participants (9%) did not fully complete the questionnaire. Missing values were inputted using the expectation-maximization (EM) method15 after finding no statistically reliable deviation from randomness using Little’s MCAR test: χ2=158.91, df=147, P=0.237. Items that elicited negative responses were reverse scored for analysis. Cronbach’s alphas for each construct of the questionnaire were used to assess the internal consistency of each construct, and they were all above 0.70 (see Tables 2A-D). One-way ANOVAs and linear regressions were used to assess the influence of demographic variables on the results observed, and to compare student-preceptor means on identical items. An overall significance value of P<.01 was used to control for multiple comparisons; however, one interesting finding at P=.017 was included. Preceptors who reported supervising more than one student (N=2) were removed from analyses examining sex-discrepancy between preceptor and student. Approval for this investigation was received from the Institutional Review Board of the McGill University Faculty of Medicine.

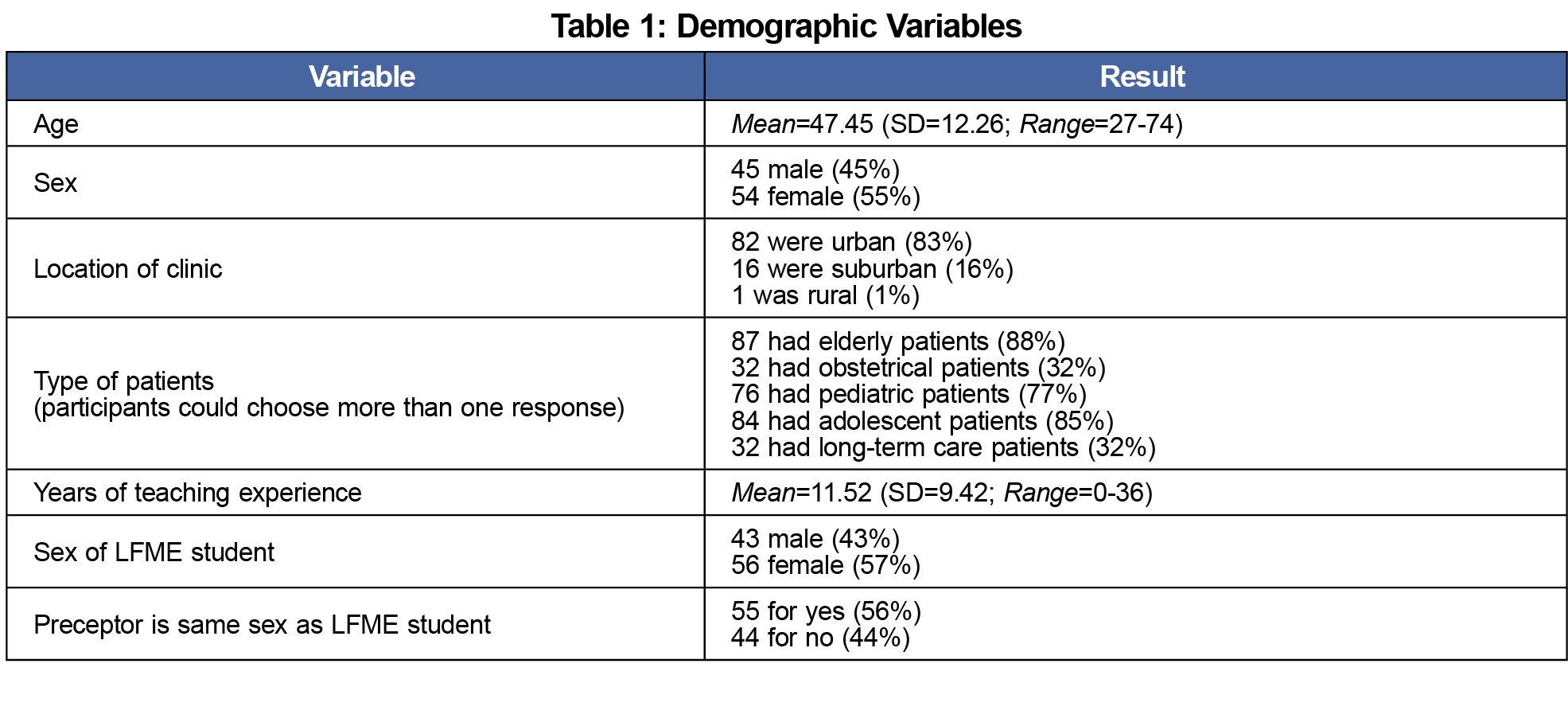

A total of 99 preceptors (57% response rate) completed the questionnaire. Demographic data for the preceptors are presented in Table 1. Mean scores for each item, as well as composite means and Cronbach’s alphas for each construct are presented in Tables 2A-D. Compared to older preceptors, younger preceptors were more likely to self-report feeling: (1) challenged as a role model in the presence of a student (F=9.81; P=.002), (2) motivated for this kind of teaching for the remuneration (F=11.66, P=.001), (3) their student was less motivated to learn and did not feel comfortable with patients (F=7.18, P=.009), (4) more students will be interested in a career in family medicine as a result of the LFME (F=8.10; P=.005), (5) it was challenging to balance time teaching a student with maintaining a busy practice (F=10.37; P=.002), and (6) the presence of a student makes additional demands on their time (F=7.44; P=.008). Preceptors with less teaching experience were more likely to self-report: (1) that they offered feedback to students about their strengths and weaknesses in their history-taking and physical exam skills (F=5.94; P=.017), (2) it was challenging to balance time teaching a student with maintaining a busy practice (F=14.09; P=.000), and (3) their student had difficulty making travel arrangement to their clinic (F=8.71; P=.004).

Female preceptors were more likely to report feeling less confident in their ability to teach students (F=8.38; P=.005), having a challenging time balancing LFME teaching with maintaining their practice (F=10.19; P=.002), and having a student causes additional demands on their time (F=14.63; P=.000), compared to male preceptors. Preceptors who supervised a student of the same sex were more likely to report their patients were accommodating when a medical student was present (F=9.69; P=.002), compared to preceptors who supervised a student of the opposite sex. Further analysis revealed that patients were more accommodating with a female-female preceptor-student pairing (N=32), as compared to a female-male preceptor-student pairing (N=20; F=12.73; P=.001), a male-female preceptor-student pairing (N=23; F=7.76; P=.007), or a male-male preceptor-student pairing (N=22; F=4.32; P=.043). Preceptors who supervised a student of the same sex were also more likely to report feeling motivated for this kind of teaching because it keeps them up to date (F=10.23; P=.002), and that the LFME was an appropriate and valuable educational experience for students (F=9.48; P=.003). Preceptors working in suburban areas were more likely to report their LFME experience inspired them to continue as an LFME preceptor (F=6.98; P=.010), compared to preceptors working in urban areas. The sex of the student had no significant impact on any of the self-report rating from preceptors.

In terms of course logistics, preceptors appeared to have some difficulty providing enough time for teaching and determining how to best meet course expectations (see Tables 2A-D for means). They were, however, highly motivated to become an LFME preceptor, especially to be able to contribute to students’ professional development. Preceptors enjoyed the LFME course, felt they developed good mentoring relationships, felt confident in their ability to teach, and were interested in receiving feedback on their performance.

The online student version of the questionnaire was completed by 120 students (65% response rate). Preceptors and students did not significantly differ in their overall ratings regarding their satisfaction with the LFME, as both groups were satisfied with the quality of the LFME and felt it was an appropriate and valuable educational experience (see Tables 2A-D for group comparison results). However, preceptors had more positive ratings regarding their role and the perceived effects of the course than did students. For example, compared to students, preceptors were significantly more likely to report that students were given sufficient opportunity to practice clinic skills, and that they gave sufficient feedback to their student about their clinical skills. In addition, preceptors were more likely than students to report that the LFME: (1) helped students feel more prepared for clerkship; (2) gave students a better understanding of the work performed by family physicians; (3) helped students develop greater empathy toward patients; and (4) would result in more students pursuing family medicine.

This study corroborates the perceived high benefits of longitudinal family medicine and primary care experiences for medical students found in previous studies,6-10 and makes two important original contributions to this body of knowledge. First, it provides a detailed portrait of preceptors’ views about this educational innovation (to our knowledge, the first in the Canadian context), when the focus of prior studies assessing similar interventions has been mostly on students’ assessments.9 Knowing preceptors’ views about the course is important to strengthen their identity as educators,16 to identify areas of improvement, and to identify motivational factors that may help to recruit and retain preceptors in the future. Second, our work has allowed the creation of two LFME questionnaires—student11 and preceptor versions—that can be further validated and used in future cohorts or adapted for different medical schools using similar longitudinal, preclerkship courses in primary care.

Our analyses of demographic factors revealed that preceptors who were younger, less experienced, and female found it more challenging to balance time teaching with maintaining their practice. These results are consistent with frequent reports of increased workload and less productivity from family medicine clerkship preceptors.10 We found that preceptors with less teaching experience reported that they offered more feedback about their students’ strengths and weaknesses in their history taking and physical exam skills than preceptors with more teaching experience. The amount of feedback provided by preceptors was one area where students and preceptors significantly differed in their perceptions, with preceptors reporting they provided more feedback than the students felt they received. A similar result was found in a study comparing surgery residents’ and preceptors’ perceptions of feedback, where 86% of preceptors felt they often/always gave feedback immediately after an activity, but only 12.5% of residents agreed.17 Finally, female preceptors of female students were most likely to report their patients were accommodating to a student, suggesting patients prefer to see students of the same sex as their physician, especially if they are female.

Preceptors’ self-reported ratings revealed they were highly motivated to teach, felt they developed good mentoring relationships, felt confident in their ability to teach, and were interested in receiving feedback on their performance. Comparisons between preceptor and student surveys indicated that both groups were very satisfied with the LFME course. However, preceptors had much more positive ratings regarding the amount of feedback and practice of clinical skills that they provided students, as well as the impact and perceived benefits of the LFME on students. Similar findings were reported in a study comparing pharmacy students’ and preceptors’ perceptions of preceptor teaching behaviors, with preceptors overestimating the quality of their performance relative to the students’ assessments.18 This discrepancy in ratings between preceptors and students highlights the need to gather input from multiple perspectives when evaluating new initiatives in order to fully understand the experience and improve the course for future iterations.

Limitations of this study include relying on self-reported data gathered at a single point in time at a single medical school, and the lack of a control group. In addition, given our low response rate (57%), it is possible that that selection bias could explain some of our findings. This was an exploratory evaluative research study conducted on the first edition of the McGill LFME course, and our aim is to overcome these limitations in future investigations. Future research should longitudinally examine, the nature of the relationships between medical students and community preceptors, and the impact of early exposure to primary care on objective outcomes such as students’ family medicine clerkship evaluations and choice of residency.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this study was provided by the College of Family Physicians of Canada through a 2014 Janus Research Grant.

Parts of this study were presented at:

- 2017 North America Primary Care Research Group (NAPCRG) Annual Meeting. Montreal, Quebec, Canada, November 17-21, 2017.

- Family Medicine Forum. Montreal, Quebec, Canada, November 8-11, 2017.

References

- Norris TE, Schaad DC, DeWitt D, Ogur B, Hunt DD; Consortium of Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships. Longitudinal integrated clerkships for medical students: an innovation adopted by medical schools in Australia, Canada, South Africa, and the United States. Acad Med. 2009;84(7):902-907.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a85776.

- Hirsh D, Gaufberg E, Ogur B, et al. Educational outcomes of the Harvard Medical School-Cambridge integrated clerkship: a way forward for medical education. Acad Med. 2012;87(5):643-650.

https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31824d9821.

- Fernald DH, Staudenmaier AC, Tressler CJ, Main DS, O’Brien-Gonzales A, Barley GE. Student perspectives on primary care preceptorships: enhancing the medical student preceptorship learning environment. Teach Learn Med. 2001;13(1):13-20.

https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328015TLM1301_4.

- Karras B, Andres D, McKague M. Student outcomes of a new preclerkship family medicine longitudinal program. Poster abstract presented at the Family Medicine Forum, Quebec City, Canada, November 12-14, 2014. Available online at http://fmf.cfpc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/RESEARCH-DAY.pdf

- Rooks L, Watson RT, Harris JO. A primary care preceptorship for first-year medical students coordinated by an Area Health Education Center program: a six-year review. Acad Med. 2001;76(5):489-492.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200105000-00024.

- Littlewood S, Ypinazar V, Margolis SA, Scherpbier A, Spencer J, Dornan T. Early practical experience and the social responsiveness of clinical education: systematic review. BMJ. 2005;331(7513):387-391.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.331.7513.387.

- Dornan T, Littlewood S, Margolis SA, Scherpbier A, Spencer J, Ypinazar V. How can experience in clinical and community settings contribute to early medical education? A BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2006;28(1):3-18.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590500410971.

- Yardley S, Littlewood S, Margolis SA, et al. What has changed in the evidence for early experience? Update of a BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2010;32(9):740-746.

https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.496007.

- Thistlethwaite JE, Bartle E, Chong AA, et al. A review of longitudinal community and hospital placements in medical education: BEME Guide No. 26. Med Teach. 2013;35(8):e1340-e1364.

https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.806981.

- Turkeshi E, Michels NR, Hendrickx K, Remmen R. Impact of family medicine clerkships in undergraduate medical education: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2015;5(8):e008265.

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008265.

- Willoughby KA, Rodríguez C, Boillat M, et al. Assessing students’ perceptions of the effects of a new Canadian longitudinal pre-clerkship family medicine experience. Educ Prim Care. 2016;27(3):180-187.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14739879.2016.1172033.

- Pichlhöfer O, Tönies H, Spiegel W, Wilhelm-Mitteräcker A, Maier M. Patient and preceptor attitudes towards teaching medical students in General Practice. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13(1):83.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-13-83.

- von Below B, Hellquist G, Rödjer S, Gunnarsson R, Björkelund C, Wahlqvist M. Medical students’ and facilitators’ experiences of an Early Professional Contact course: active and motivated students, strained facilitators. BMC Med Educ. 2008;8(1):56.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-8-56.

- Hampshire AJ. Providing early clinical experience in primary care. Med Educ. 1998;32(5):495-501.

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00243.x.

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(2):147-177.

https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147.

- Starr S, Ferguson WJ, Haley HL, Quirk M. Community preceptors’ views of their identities as teachers. Acad Med. 2003;78(8):820-825.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200308000-00017.

- Sender Liberman A, Liberman M, Steinert Y, McLeod P, Meterissian S. Surgery residents and attending surgeons have different perceptions of feedback. Med Teach. 2005;27(5):470-472.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0142590500129183.

- Sonthisombat P. Pharmacy student and preceptor perceptions of preceptor teaching behaviors. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(5):110.

https://doi.org/10.5688/aj7205110.

There are no comments for this article.