Introduction: Comprehensive medical care should embody the biopsychosocial care model and encompass all aspects of health. Sexual health topics may be overlooked or avoided because of patient and provider discomfort. Our purpose was to better understand patients’ preferences about discussing sexual concerns in primary care. We hypothesized that most individuals have sexual concerns, but many barriers prevent them from seeking care.

Method: We surveyed patients at a family medicine residency program office. The survey explored whether patients had experienced sexual concerns, preferences for addressing concerns in the office, and barriers and facilitators to addressing concerns. Results were analyzed using counts and proportions. Pearson correlations, Pearson 𝜒2 analyses, and independent samples t-tests were used to explore demographic differences in responses.

Results: Most participants indicated that physicians should ask all patients about having sexual concerns and that physicians should initiate these conversations. Younger participants were more likely to have this preference. Participants identified embarrassment as the most common barrier to sexual health conversations. Participants indicated it was easier to discuss sexual concerns with physicians of the same gender and/or a physician they had seen before.

Conclusions: The majority of patients prefer active inquiry about sexual health concerns from primary care physicians. However, because a large minority prefer not to be asked about sexual health, physicians should inquire sensitively, particularly with older patients. Continuity of patient-physician relationship and allowing patients to choose their provider based on gender may also help facilitate these discussions.

Comprehensive sexual health, including physical, mental, and social aspects of sexual health, is frequently overlooked in primary care physician offices.1-5 Most providers limit discussion to addressing contraception, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), or a specific concern raised by the patient.5-6 Sociocultural taboos related to sexuality contribute to the hidden epidemic of STIs in the United States.7 A survey done in the late 1990s showed that 71% of patients 25 years and older felt a doctor would dismiss their sexual concern if they brought one up.8 Many providers also believe older individuals are not interested in sexual health,6,9 and the majority do not view themselves as adequately trained to comprehensively address sexual concerns.5 However, with the notable exception of studies of gay and lesbian patients,9 few studies have focused on actual patient perceptions of the barriers to discussing sexual health.

Our primary purpose was to better understand patients’ preferences about discussion of sexual concerns in primary care. A secondary purpose was to identify both patient-reported barriers to discussion and practices that make discussion easier. We hypothesized that most individuals have sexual concerns, but many barriers prevent them from raising those concerns with physicians.

We surveyed older adolescent and adult patients at a family medicine residency program health center in fall of 2016. The health center is located in a town of less than 10,000 people. We were not able to identify an existing validated instrument that met our needs, and thus developed a new survey. The survey was constructed with the input of several residents and faculty, including a social worker, and written for a low health literacy population. The 14-item survey included Likert scale, multiple choice, and free response questions. Because the only health center providers are physicians and resident physicians, the questionnaire inquired about physicians rather than providers.

Health center staff solicited patient participation during check-in for appointments of all types. Written consent was obtained. The Sparrow Health System Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Data were analyzed using counts and proportions. Pearson correlations, Pearson 𝜒2 analyses, and independent samples t-tests were used to explore demographic differences in responses. Because of the small sample size, some response categories were collapsed before analysis.

Seventy-nine patients returned usable questionnaires. Because of inconsistencies in staff documentation, an accurate response rate could not be calculated. Demographics are listed in Table 1. Participants were comparable in age to the general adult population of the health center (median age 47), but women were over-represented (69% vs 55%, P=0.01). The majority of participants were women, straight, and in relationships. The majority had experienced a sexual concern, and most of these had discussed the concern with their primary care physician. Having or discussing a sexual concern was neither correlated to age nor associated with gender. Those in relationships were more likely to report having had a sexual concern (P=0.048) and discussing this concern with a primary care physician (P=0.020).

Initiating Discussion of Sexual Concerns

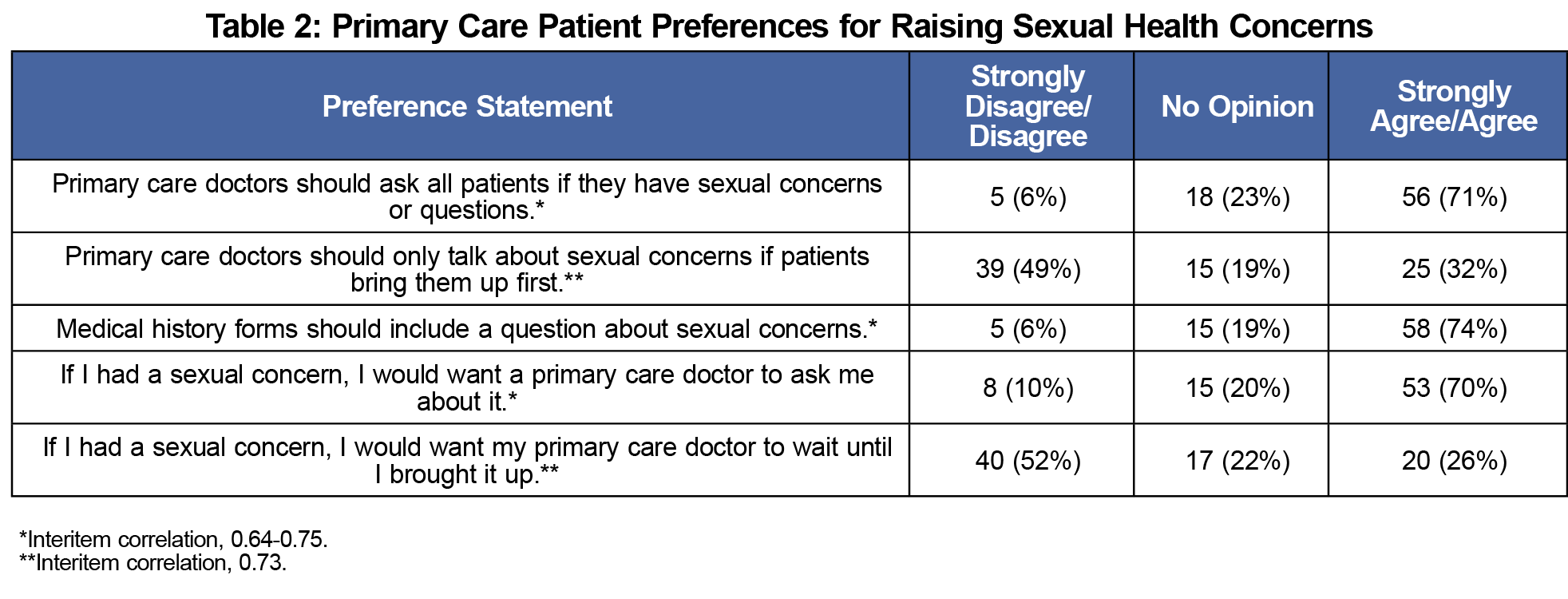

The majority of patients indicated that primary care doctors should ask all patients about sexual concerns, that medical history forms should include a question about sexual concerns, and that they personally would prefer to be asked about a sexual concern (Table 2). Most did not agree that providers should wait for patients to raise these concerns (Table 2). However, older patients were more likely to agree that “if I had a sexual concern, I would want my primary care doctor to wait until I brought it up” and that “primary care doctors should only talk about sexual concerns if patients bring them up first” (P=0.018 and P=0.004, respectively). Younger patients were more likely to indicate “primary care doctors should ask all patients if they have sexual concerns or questions” (P=0.02). These items were assessed further using interitem correlations, which confirmed internal validity (Table 2). Patients preferring physician-initiated discussion also preferred that forms include sexual health questions (interitem correlation, 0.64-0.75).

Barriers to Discussion

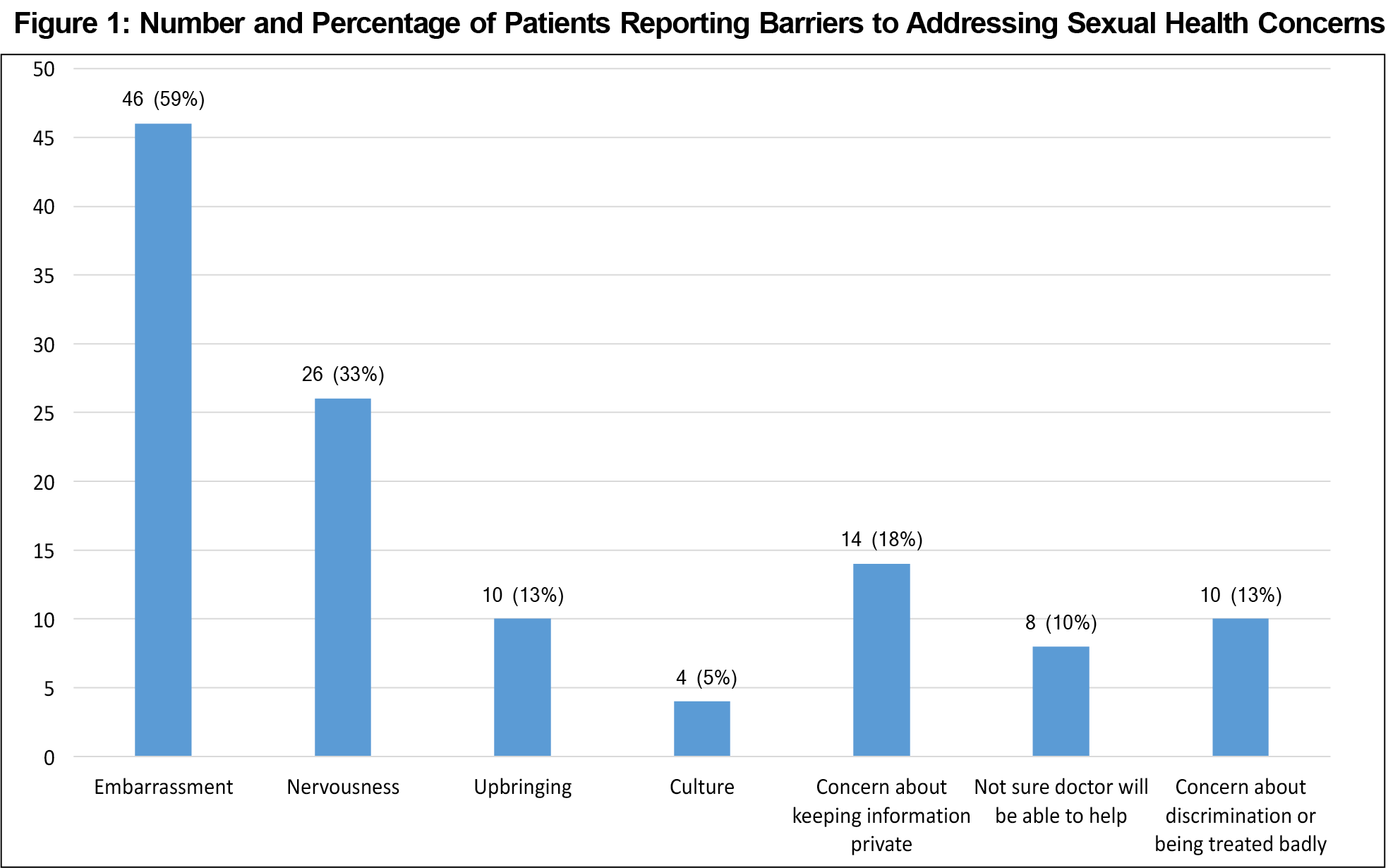

“Embarrassment” (46, 59%) and “nervousness” (26, 33%) were the most common barriers to discussing sexual concerns, followed by “concern about keeping information private” (14, 18%; Figure 1). Younger patients were more likely to identify “embarrassment” and “concern about discrimination or being treated badly” as barriers (P=0.001 and P<0.001, respectively). There were no significant differences in response by gender.

Facilitators of Discussion

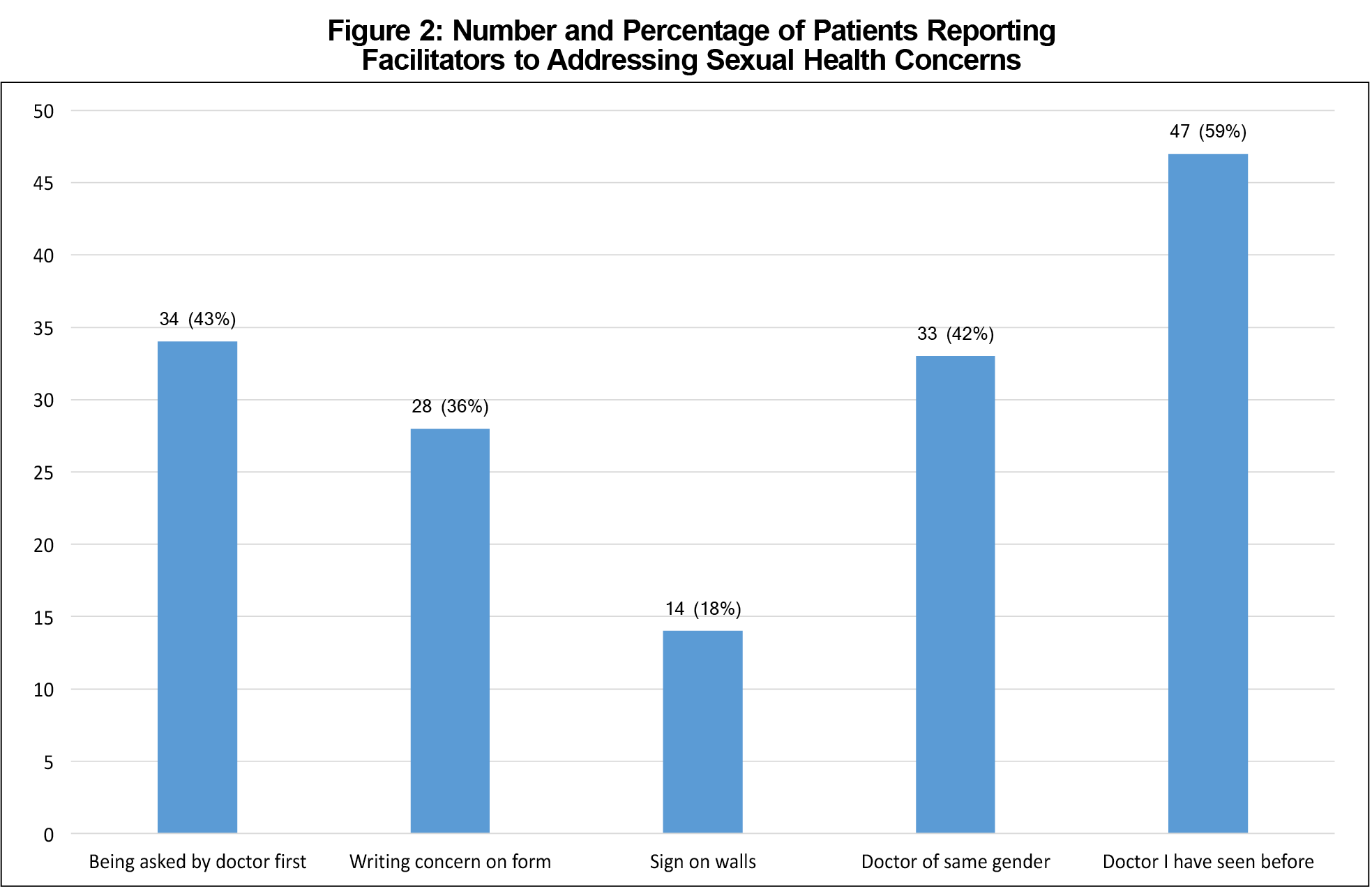

Patients most often indicated that having met the physician previously (47, 59%), physician initiating the conversation (34, 43%), and having a physician of the same gender (33, 42%) made discussion of sexual concerns easier. Younger patients were more likely to indicate that writing their concern on a medical history form would make discussions easier (P=0.022; Figure 2). Women were more likely to indicate that discussion was easier with a same-gender physician (P=0.003) or a physician they had met previously (P=0.013).

Although we solicited free-text responses about barriers and facilitators of discussion, very few patients responded. Therefore, meaningful analyses could not be conducted.

Sex is an important part of health and quality of life. Our results affirm that many primary care patients, regardless of age or gender, have experienced sexual concerns. A majority of patients prefer that physicians initiate discussions of sexual health and that offices screen for sexual concerns by asking about them on intake forms. However, a substantial minority of patients did not want physicians to ask about sexual health, suggesting that these conversations should be handled with sensitivity. In our practice, these patients were more likely to be older.

Our study also indicated that offices may assist patients in the process of addressing sexual health concerns by supporting patient-provider continuity. Patients, particularly women, also indicated more comfort discussing sexual concerns with physicians of the same gender. Although allowing patients to choose providers may not always be possible, practices should be aware of this barrier to discussion, and consider exploring it with patients as they choose providers, whether for an ongoing relationship or an urgent concern. Physicians may also benefit from being cognizant of gender disparities when addressing sexual concerns with patients.

This study has important limitations. The sample size was small, and response rate could not be calculated, limiting generalizability. Women were over-represented in the study. The survey tool was not formally validated. Half of participants (39) did not answer the sexual orientation question. This may be because of the question’s placement on the page, but could also be due to participant confidentiality concerns. Although the survey was anonymous, surveys were collected by office staff. Nearly all responding survey participants identified as heterosexual, which meant that the perspectives of LGBTQ patients could not be captured. The sample was distributed at only one medical site in the community, a small town in the United States with a Caucasian majority. The study sample itself was also predominantly female, heterosexual, and in a committed relationship. Findings may not be generalizable to other populations. It would be useful to conduct larger studies among more diverse populations in order to better capture diverse patient perspectives.

In conclusion, our study supports current best practices of screening primary care patients for sexual concerns, both by asking patients and using screening intake forms.1,2,6

Acknowledgments

This study was presented at the Michigan Family Medicine Research Day, May 25, 2017, Howell, Michigan.

References

- Clegg M, Towner A, Wylie K. Should questionnaires of female sexual dysfunction be used in routine clinical practice? Maturitas. 2012;72(2):160-164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.03.009.

- Briedite I, Ancane G, Ancans A, Erts R. Insufficient assessment of sexual dysfunction: a problem in gynecological practice. Medicina (Kaunas). 2013;49(7):315-20. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina49070049

- Hinchliff S, Gott M. Seeking medical help for sexual concerns in mid- and later life: a review of the literature.” J Sex Res. 2011 Mar;48(2-3):106-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2010.548610

- Kottmel A, Ruether-Wolf KV, Bitzer J. Do gynecologists talk about sexual dysfunction with their patients?” J Sex Med. 2014 Aug;11(8):2048-54. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12603

- Wimberly YH, Hogben M, Moore-Ruffin J, Moore SE, Fry-Johnson Y. Sexual history-taking among primary care physicians. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(12):1924-1929.

- Althof SE, Rosen RC, Perelman MA, Rubio-Aurioles E. Standard operating procedures for taking a sexual history. J Sex Med. 2013 Jan;10:26-35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02823.x

- Eng T, Butler W; Committee on Prevention and Control of Sexually Transmitted Disease, Institute of Medicine. The Hidden Epidemic. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1997.

- Marwick C. Survey says patients expect little physician help on sex. JAMA. 1999;281(23):2173-2174. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.281.23.2171c

- Taylor A, Gosney MA. “Sexuality in older age: essential considerations for healthcare professionals.” Age Ageing. 2011 Sep;40(5):538-43. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afr049

- Bitzer J, Giraldi A, Pfaus J. Sexual desire and hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women. Introduction and overview. Standard operating procedure (SOP Part 1). J Sex Med. 2013 Jan;10:36-49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02818.x

- Austin EL. Sexual orientation disclosure to health care providers among urban and non-urban southern lesbians. Women Health. 2013;53:41-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2012.743497

- Latif EZ, Diamond MP. Arriving at the diagnosis of female sexual dysfunction. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(4):898-904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.08.006

There are no comments for this article.