Introduction: National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) subject examinations are used by many schools to assess student clinical knowledge. Studies indicate that mean scores on NBME examinations improve as the clinical year progresses. Literature review revealed no studies investigating changes in individual student scores when end-of-block examinations were repeated at the end of the clinical year. This study investigated NBME family medicine subject examination score changes for students who opted to repeat the examination at the end of the academic year.

Methods: In 2014, students on a 4-week family medicine block clerkship took the NBME subject examination at the end of their clerkship block and were offered the opportunity to repeat this examination at the end of that clinical year; 25 of 80 students voluntarily repeated the examination. Paired t-tests were used to compare performance outcomes between the exam means at the end of the clerkship blocks to the means on the exam administration at the end of the academic year.

Results: Results showed a statistically significant improvement in scores between the first and second examination administration. Examinations given immediately after the students’ clinical experience yielded scaled scores ranging from 60 to 80 compared to the national mean of 71.9. Examinations given at the end of the clinical year yielded scaled scores ranging from 57 to 90 (t[24]=-2.66, P=0.0006).

Conclusion: Repeating the NBME subject examination at the end of the year led to slightly increased scores, suggesting that time spent during clerkships influences examination performance.

National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) subject examinations are used by many schools to assess student clinical knowledge during clerkships. Several studies have demonstrated that mean scores on NBME examinations improve as the clinical year progresses.1-3 For instance, from 1983 to 1986, scores on the internal medicine NBME examination, given at the end of a 12-week clerkship, steadily improved over the clinical year at the University of Illinois College of Medicine at Chicago.1 A similar study evaluating 12-week surgery clerkships from 1985 to 1986 at the Medical College of Ohio-Toledo, demonstrated that students performed better during blocks later in the clinical year.2 Analysis of all NBME surgery examinations across the United States from August 1, 1994 to July 31, 1995 revealed that students had higher scores when their surgery rotation was last in their clinical year and when they had longer rotations (12 weeks as opposed to 8 weeks).3 Additionally, evaluation of 16,091 students from 67 US schools graduating 2012-2013 showed that completing surgery, pediatrics, and family medicine rotations prior to taking the internal medicine NBME examination significantly improved scores, with the largest benefit observed when surgery was taken first.4

Between 2011 (when Florida International University Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine’s first class of students reached their clinical years) and 2014, our family medicine clerkship evolved from a longitudinal clerkship for 43 students, to a 6-week block for 43 students, then to a 4-week block for 80 students. There was concern that student NBME subject examination scores would decrease with the change from a 6-week to a 4-week block, which led to the decision to allow students to voluntarily repeat the NBME examination at the end of the clinical year. We hypothesized that individual student NBME scores would increase when students were allowed to repeat the examination, and that changes in NBME scores could potentially impact the students’ clerkship summative grades.

Students who had passed the NBME examination during their initial clerkship block were offered the opportunity to repeat the examination at the end of the clinical year, in March 2014. Between April 2013 and March 2014, 80 students completed the family medicine rotation and 25 students opted to repeat the NBME subject examination. Two students voluntarily repeated the entire clinical year; their scores were not included in this analysis. Individual student scores on the initial and second administration of the NBME Family Medicine Core subject exam were compared. The greater of the two scores was used in the calculation of the student’s summative clerkship grade. Paired t-test analysis was conducted to compare performance differences between the two administrations of the NBME family medicine subject examination. The Florida International University Health Sciences Institutional Review Board granted the study exemption.

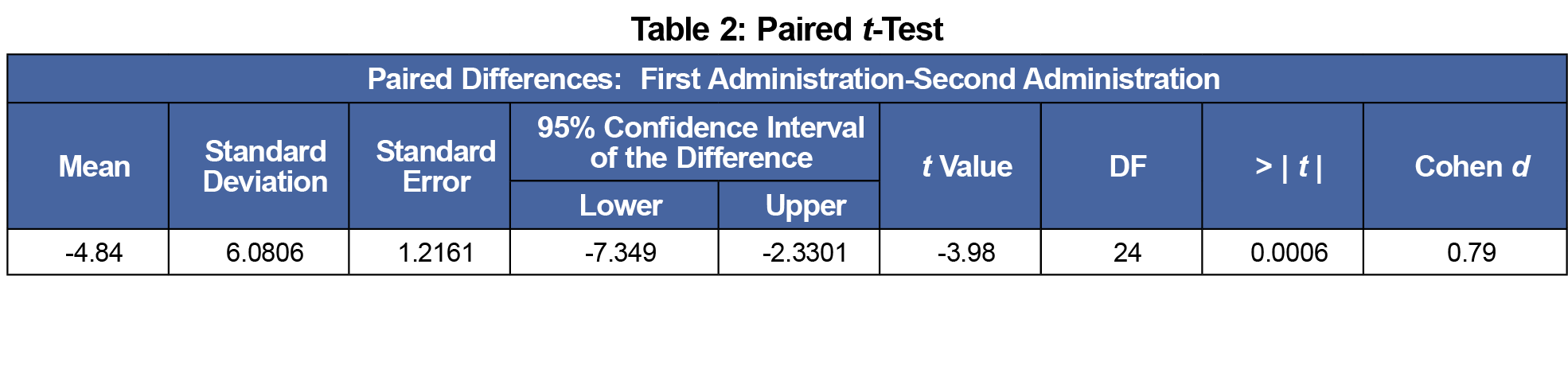

Between one and six students in all blocks chose to repeat the NBME examination. Half of the students who chose to repeat the examination completed the clerkship before the midpoint of the clinical academic year, and half took the course after the midpoint. Students scored a mean of 67.68 (with a range of 60 to 80, scaled scores) on the first examination, administered at the end of the rotation, compared to the national mean of 71.9. Students scored a mean of 72.52 (with a range of 57 to 90, scaled scores) on the second administration, given at the end of the clinical year (Table 1). Effect size between the two administrations was measured using Cohen d, which indicated a large effect size at 0.79. The paired t-test (Table 2) indicated a statistically significant difference in scores between the first and second examination administration (t[24]=-3.98, P=.0006.

Improved scores on the second administration of the NBME examination led to 11 students’ overall final clerkship summative grades improving by one to four points on a 100-point scale.

These results affirm that time spent on clerkships may influence family medicine NBME examination performance; although results may also have improved on the second administration simply due to increased familiarity with the family medicine NBME examination structure and content. Ultimately, repeating the family medicine NMBE subject examination at the end of the year led to slight, but variable, improvement in scores. Any increase in NBME scores may have further significance, such as influencing final clerkship grades.

Half of the students choosing to repeat the examination completed the clerkship before the midpoint of the clinical academic year, while half took the course after the midpoint. This was unexpected, as we had anticipated that students from the first half of the year would be more likely to choose to repeat the examination as these students tend to struggle with it more, having experienced fewer rotations. There was an average increase of 7.4 points for the 18 students who showed an increase in scores from the first administration to the second administration. Two students had no change in scores. Scores for five students dropped from the first to the second administration, with an average decline of 2.4 points. It is unclear why this drop occurred; this may have been due to a lack of dedicated study time for the second administration of the exam.

This study has several important limitations. Students chose whether or not to repeat the NBME examination, which may have introduced selection bias. High-achieving students and students planning family medicine careers may have been most likely to repeat the examination, and also most likely to show improvement. The study also has a small sample size. Further, we did not have demographic and specialty interest information about the study participants, and thus could not assess whether students repeating the examination were representative of the class as a whole.

Further considerations include cost and the length of the rotation. Budget approval had to be obtained in order to offer this option to students. Additionally, the option to repeat the NBME subject examination was offered to students due to concerns that 4 weeks was not sufficient time to study. For a 6- or 8-week block, repeating this examination may be less useful.

Future researchers may compare larger sample sizes of students completing the examination at the actual end-of-clerkship rotation by block or quarter to end-of-year examination performance. Additionally, future research may analyze the impact of repeating the exam at the end of the clinical year with a longer clerkship block and evaluate repeating NBME subject examinations in other non-family medicine clerkships.

In conclusion, repeating NBME subject examinations at the end of third year may allow students to show improvement in exam scores, and has the potential to impact students’ overall summative clerkship grades; however, more research is needed to further elucidate this phenomenon.

Acknowledgments

Presentation: Minor S, Stumbar S, Bonnin R, Samuels M. Do family medicine NBME shelf scores improve when students are allowed to repeat the NBME exam at the end of the academic year? Presentation at the 43rd Annual Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Conference on Medical Student Education, Anaheim, CA, February 11, 2017.

There are no comments for this article.