Introduction: Although there is an increasing need for geriatricians, fewer physicians are entering the field. Family medicine residents find geriatrics, especially nursing home care, unsatisfying. Life stories of older adult patients may help providers cope with the challenges of nursing home care and increase provider satisfaction by offering a way to connect with patients.

Methods: We conducted a qualitative study on life stories’ effects on attitudes towards nursing home care. Fourteen patient stories were created. Seven Boston University family medicine residents and one nurse practitioner participated in a semistructured interview both before and at least 2 months after learning about their patients’ stories. Data were analyzed using qualitative techniques from grounded theory.

Results: Participants found nursing home care challenging, particularly for patients who were nonverbal due to advanced dementia, because they had difficulties forming meaningful relationships or discussing medical decisions with their patients. Life stories increased empathy, deepened relationships with patients, and led participants to feel more satisfied in their role as providers. The stories were considered useful for end-of-life discussions.

Conclusion: Life stories incorporated into physician practice may help health care providers feel more connected to their patients and ultimately more satisfied in the care of nursing home patients.

The number of physicians entering geriatrics is projected to decline from 3.6 to one geriatrician per 10,000 older adults by 2045.1 Educational interventions to increase medical student interest have had mixed results.2-5 In 2006, longitudinal nursing home care became a requirement for family medicine training.6 Few residents, however, plan to continue with nursing home care.7 Educators believe residents are prepared for the clinical decision-making of geriatrics6 but find the population less satisfying to work with.7 Medical students and residents consider geriatrics frustrating, viewing the patients as slow and the care time consuming.8

Research suggests that interventions that build empathy lead to more positive change in attitude towards older adults.9 Our study explores the potential impact of life stories—previously shown to help other kinds of caregivers develop more empathy towards older adults—on perceptions of geriatrics. Life stories have helped nursing home staff and family understand patients’ needs10,11 and develop a change in attitudes, such as from viewing a patient as grumpy to considering the reason behind the patient’s bad mood.10 We wanted to understand the ways life stories could potentially enhance health care providers’ experiences in caring for their geriatric patients as a professional development tool. As many of our providers were resident trainees, we also wanted to understand the potential educational benefit.

Boston University School of Medicine IRB approved this study (H-33844).

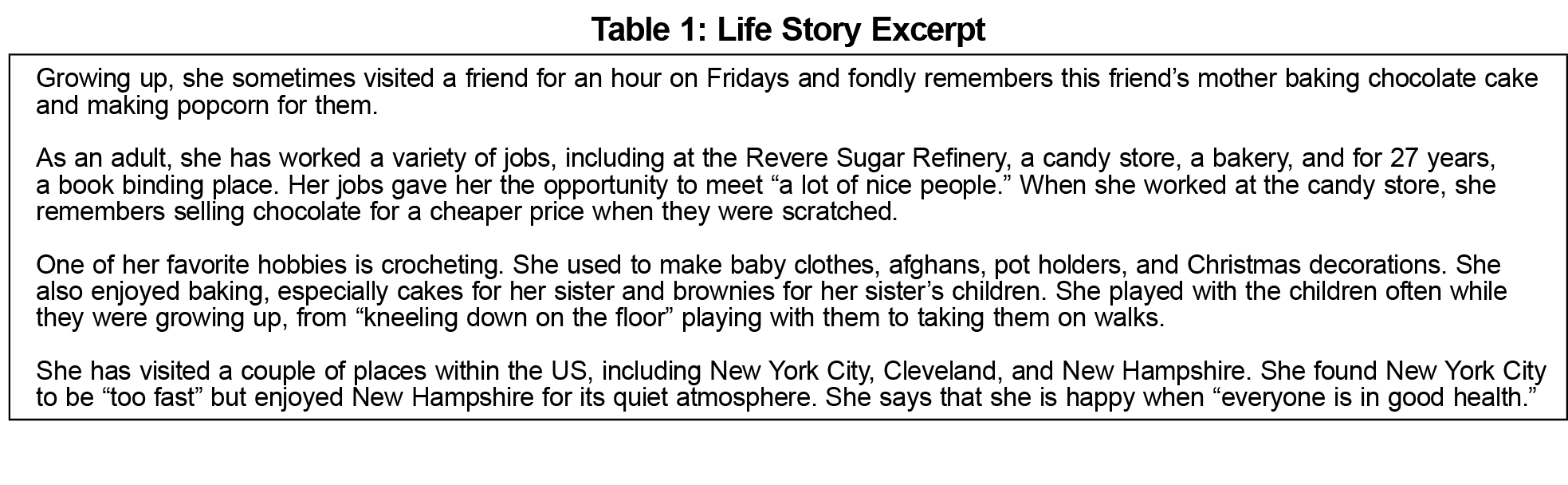

The intervention consisted of written life stories (Table 1) gathered from semistructured interviews conducted by the researcher with patients at two nursing homes affiliated with the Boston University Family Medicine Residency Program. We chose a semistructured approach to allow patients the opportunity to highlight memorable experiences; this aligned with previous life story work that used a semistructured model.12 Interviews explored patients’ education, work experiences, favorite memories, and interests. We included stories of patients with dementia if they could describe their past or had family members participate. We obtained consent in person. Patients were told that copies of their stories would be given to their providers and separately displayed in their rooms for providers to reread if they wished. Participation was voluntary; patients could decline to answer any question, and they could review their stories. We used teach back, a method where patients reiterated information described to them in their own words, to ensure understanding. Of 29 patients, we recruited 14, three declined, and 12 did not meet criteria (nonverbal without family to contribute). Of 14, three were nonverbal with family participation. Patients were not later interviewed about their experiences.

The patients’ providers (either family medicine residents or nurse practitioners) served as study participants. We included both provider types as we primarily wished to explore the role of life stories in providers’ care of their patients and wanted to experience as many different perspectives as possible. We conducted consent in person, and participation was voluntary. Participants were interviewed twice. During the first meeting, we conducted a semistructured interview to understand participants’ relationships with their patients, knowledge of patients’ stories, and thoughts on nursing home care. Participants were then provided their patients’ stories and asked initial impressions. The second meeting, occurring at least 2 months later, included the same semistructured interview with additional questions about the life stories experience. We included a pre-life story interview as we felt it was hard to assess the potential impact of the life stories without knowing more about participants’ experiences before they learned their patients’ biographies.

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Transcripts were analyzed using grounded coded theory and content analysis, as described in Chamaz’s Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis,13 to identify pre-life story and post-life story themes. The research team coded separately before reviewing together to determine categories. Categories were then grouped into themes, which were consistently confirmed by returning to the data.

Of nine family medicine residents and one nurse practitioner who cared for the 14 patients, we reached thematic saturation after recruiting five third-year residents, two second-year residents, and one nurse practitioner. The time between pre- and postinterviews ranged from 3 to 6 months. Two participants were lost to follow up: one moved to a new position and another’s patient was discharged. Participants were deidentified.

All participants expressed interest in incorporating life stories into routine nursing home care. Two pre-life story and five post-life story themes emerged from qualitative analysis, with quotations shown in Table 2.

Pre-Life Story

Communication barriers manifested in two themes that affected how participants felt about caring for their patients.

Theme 1: Surface relationships. This theme reflected thoughts on level of interaction with patients. Five participants felt their relationships with their patients were “ceremonial” and “superficial” due to difficulties connecting with them. This was particularly apparent for patients with aphasia and advanced dementia, but two participants also faced challenges building rapport with their verbal patients. Despite seeing their patients monthly, participants struggled to make substantial progress with knowing their patients better. This made them feel less connected to their patients and the care unsatisfying as they highly valued relationships.

Theme 2: Decreased confidence in nursing home care. This theme reflected the level of comfort with the care provided to patients. Participants questioned the quality of their medical care when their patients with advanced dementia could not participate in medical decisions or provide feedback. Participants often felt less confident about their decisions, including wondering how aggressively they should control certain measures like blood pressure or lipids in the context of their overall health. They felt uncertain about whether their decisions were appropriate and reflected what patients wanted.

Post-Life Story

Life stories helped alleviate some of the challenges expressed in the pre-life story themes, represented by five post-life story themes.

Theme 1: Humanization of patients. The holistic perception of patients added to the sense of a relationship. Four participants stated that the stories humanized patients. Participants were reminded—particularly for patients with advanced dementia—that there was more depth to who their patients were beyond their diagnoses. While the communication challenges remained the same, the insight helped participants feel less apathetic about the care.

Theme 2: Shadows of the patient. This involved comparing patients’ current level of function to before. For three participants, the stories exhibited the contrast between the way patients were previously compared to presently, which highlighted that they were interacting with a “shadow” of who their patients were. One participant, for example, learned that her patient enjoyed singing, but the participant had never encountered any singing during visits. Caring for patients became a harder experience emotionally when faced with the reality of the multiple losses their patients experienced.

Theme 3: Bringing meaning to the care. The stories enhanced appreciation for nursing home care. Through the stories, participants found meaning in nursing home care, particularly for patients with advanced dementia, because they understood more about their patients’ backgrounds. Participants were more prone to feel a sense of futility in caring for nonverbal older adults. In those cases, knowing more about the patients manifested in internal changes of feeling differently about them that helped bring meaning to the visits.

Theme 4: Conversation-starter. Life stories served as inspiration for conversations with patients. For verbal patients, the stories were a resource for participants to engage patients in conversation. Participants began asking questions they may not have otherwise considered beyond patients’ health. This allowed participants to build rapport with their patients and gave patients the opportunity to open up in new ways.

Theme 5: Context for end-of-life and goals of care discussions. Stories showed potential to help with end-of-life discussions. Four participants felt the life stories had content useful for end-of-life and goals of care discussions. The stories offered participants insight into their patients’ values, which participants believed could help frame discussions around maintaining interests and better facilitate goals of care conversations.

Participants found nursing home care unfulfilling because communication barriers limited feedback and shared medical decision-making. This adversely affected the ability to form meaningful relationships. With the stories, participants felt emotionally connected to their patients, having gained more understanding of their patients’ experiences and how much their patients changed. Participants saw potential in the life stories as resources for starting conversations with their verbal patients and for guiding end-of-life discussions.

Previous research on life stories in nursing homes have primarily occurred outside the United States and with nonphysician nursing home staff.10,11 US research on medical storytelling often involves medical students working with patients to appreciate illness in the context of patients’ lives.14-16 Fewer narrative studies involve residents and fellows,17 and with physicians, interventions often focus on the physician perspective: understanding patients through self-reflection.17,18 We therefore offer a novel study where providers understand patients’ perspectives through biographical data rather than illness narratives for patients in nursing homes.

Our study was limited in exploring the full scope of experiences. Our sample size was small, but we reached saturation. Each provider had only one or two patients participate in the study, with fewer life stories for patients with advanced dementia, so it was more difficult to appreciate the spectrum of experiences they could have had with the life stories. Other educational or personal experiences participants had while in the study could also affect how the stories impacted them. We did not follow participants to assess whether the life stories affected career choice. The participants were also in later years of training, long after most career choices are made. Nevertheless, the participants felt better connected to their patients. Future studies could offer life stories at the beginning of training and follow participants over time, assessing which providers continue nursing home care after residency. Future work could also include more stories for patients with advanced dementia.

More than half of nursing home patients have dementia.19 Our study suggests that life stories may alleviate frustration from lack of connection with patients, which could enhance satisfaction. Life stories may further have utility in end-of-life discussions by providing missing insight into patients’ beliefs and values. The life stories, while a helpful tool for providers to connect with their patients, may have value in educational settings, and that should be considered. Future research could explore its potential as a professional development tool for providers and as an educational tool for trainees.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: The first author (J.Q.) received a research stipend from the Medical Student Summer Research Program at Boston University to partially support her time for the project.

Presentations: The content of this study has been presented at the 2016 Summer Research Symposium of the Medical Student Summer Research Program on January 29, 2016 in Boston, MA and at the Eleventh Annual John McCahan Medical Campus Education Day on May 25, 2016 in Boston, MA.

References

- Health in Aging Foundation. Facts and Figures. http://www.healthinagingfoundation.org/who-we-are/facts-figures/. Accessed August 20, 2017.

- Alford CL, Miles T, Palmer R, Espino D. An introduction to geriatrics for first-year medical students. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(6):782-787. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49156.x

- Eskildsen MA, Flacker J. A multimodal aging and dying course for first-year medical students improves knowledge and attitudes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1492-1497. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02363.x

- Meiboom AA, de Vries H, Hertogh CMPM, Scheele F. Why medical students do not choose a career in geriatrics: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):101. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0384-4

- Adelman RD, Capello CF, LoFaso V, Greene MG, Konopasek L, Marzuk PM. Introduction to the older patient: a “first exposure” to geriatrics for medical students. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(9):1445-1450. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01301.x

- Raetz J, Unwin B, Andrilla HA. Attitudes and barriers encountered in training family medicine residents in nursing home care: a national survey of program directors: a CERA study. Fam Med. 2016;48(4):309-313.

- Helton MR, Pathman DE. Caring for older patients: current attitudes and future plans of family medicine residents. Fam Med. 2008;40(10):707-714.

- Higashi RT, Tillack AA, Steinman M, Harper M, Johnston CB. Elder care as “frustrating” and “boring”: understanding the persistence of negative attitudes toward older patients among physicians-in-training. J Aging Stud. 2012;26(4):476-483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2012.06.007

- Samra R, Griffiths A, Cox T, Conroy S, Knight A. Changes in medical student and doctor attitudes toward older adults after an intervention: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(7):1188-1196. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12312

- Clarke A, Hanson EJ, Ross H. Seeing the person behind the patient: enhancing the care of older people using a biographical approach. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12(5):697-706. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00784.x

- Kellett U, Moyle W, McAllister M, King C, Gallagher F. Life stories and biography: a means of connecting family and staff to people with dementia. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(11-12):1707-1715. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03116.x

- Thompson R. Using life story work to enhance care. Nurs Older People. 2011;23(8):16-21. https://doi.org/10.7748/nop2011.10.23.8.16.c8713

- Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications; 2006.

- Chretien KC, Swenson R, Yoon B, et al. Tell Me Your Story: A Pilot Narrative Medicine Curriculum During the Medicine Clerkship. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(7):1025-1028. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3211-z

- Kumagai AK, Murphy EA, Ross PT. Diabetes stories: use of patient narratives of diabetes to teach patient-centered care. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2009;14(3):315-326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-008-9123-5

- Garrison D, Lyness JM, Frank JB, Epstein RM. Qualitative analysis of medical student impressions of a narrative exercise in the third-year psychiatry clerkship. Acad Med. 2011;86(1):85-89. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ff7a63

- Khorana AA, Shayne M, Korones DN. Can literature enhance oncology training? A pilot humanities curriculum. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(4):468-471. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.33.3617

- Charon R. Narrative and medicine. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(9):862-864. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp038249

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alzheimer’s Disease. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/alzheimers.htm. Accessed March 31, 2017.

There are no comments for this article.