Background: Multiple studies have shown that the majority of health care practitioners do not routinely screen for intimate partner violence (IPV); lack of provider preparedness and education is an often-cited barrier to screening. Our third-year family medicine clerkship includes a pregnancy options counseling objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) that requires students to review a preencounter online educational module that highlights screening guidelines for IPV and reproductive coercion. The goal of this study was to explore students’ internal barriers to screening patients for IPV and reproductive coercion, and whether our curricular interventions adequately addressed these barriers.

Methods: We administered an immediate postencounter, anonymous, online survey with open-ended and Likert-type questions to 118 medical students during the 2016 academic year. We used an exploratory, iterative process to analyze qualitative responses and quantify recurrent and commonly identified themes.

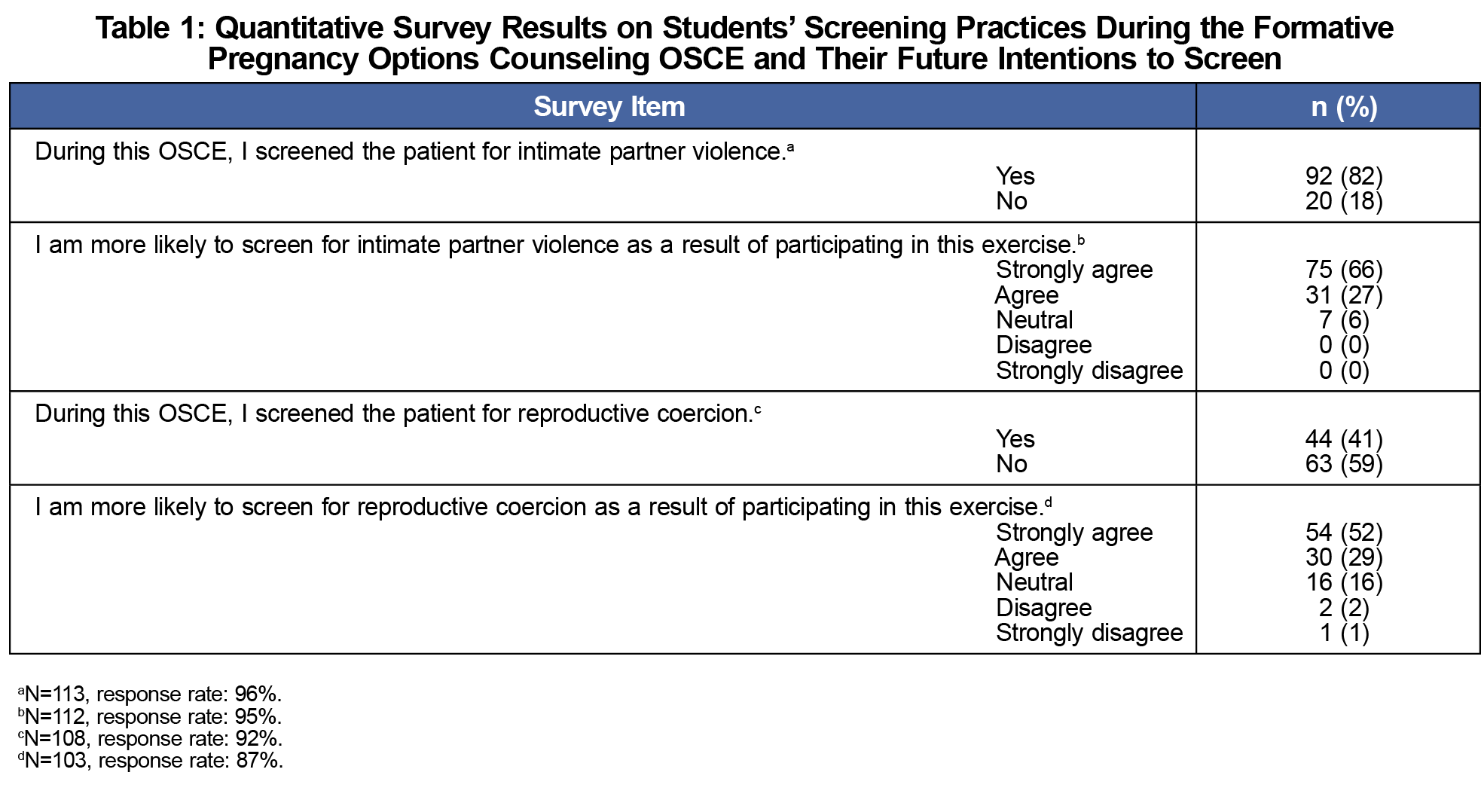

Results: After the OSCE, students reported they were more likely to screen for IPV (94%) and reproductive coercion (82%) in future encounters. Qualitative analysis revealed two major types of barriers to screening: internal barriers concerning the screening inquiry itself and concerns regarding handling of patients’ responses.

Conclusions: The online preparatory module and subsequent OSCE provided a low-stakes environment in which to practice screening. However, student comments about their barriers to screening suggest that a first or early curricular intervention folding IPV and reproductive coercion into an educational module on pregnancy options counseling did not optimally promote this screening behavior.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) encompasses any form of assault intended to isolate and/or intimidate, including physical and psychological abuse, reproductive coercion, and stalking.1 Reproductive coercion refers to any behavior that manipulates reproductive health outcomes, such as sabotaging birth control methods, pressuring a woman to get pregnant or a man to father a child, or exerting control over the outcome of a pregnancy.2,3 Multiple studies have examined the prevalence of reproductive coercion in different populations of women, with reported prevalence ranging from 16% to 54%.4-6

While research suggests that most health care practitioners do not routinely screen patients for IPV, data on screening practices for reproductive coercion are scant.7,8 An often-cited barrier to IPV screening is the lack of provider education.7,9 One study conducted interviews with 15 medical students to elucidate their barriers to screening, with fear of offending the patient, lack of training and knowledge, and time constraints frequently reported as concerns.10

As studies have shown that health care practitioners are more likely to screen if they have received IPV training, the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) National Clerkship Curriculum supports the inclusion of this material in clerkships.11 The extent of IPV education directly correlates with comfort and knowledge regarding the topic.7,9,12 While nearly all US medical schools have required coursework on domestic violence, the quality of this course content is highly variable.13,14 Recent reports have described specific interventions aimed at improving medical students’ knowledge of IPV, but have not looked specifically at reproductive coercion.15,16

In order to optimize educational interventions, the objectives of our study were to further elucidate the internal barriers that medical students face when presented with the opportunity to screen for IPV and reproductive coercion, and to describe how our curriculum on this topic could be improved to better address these barriers.

During the 2016 academic year, immediately after the pregnancy options counseling OSCE, students completed an optional, anonymous survey with Likert-type and open-ended questions evaluating the self-perceived impact of this session on their IPV and reproductive coercion screening practices.

We completed an exploratory thematic analysis of responses to the open-ended survey questions using an iterative process. First, two coders independently coded the responses. We developed a final codebook through consensus, and responses were then recoded using this codebook. We used NVivo 11 (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) for data management and to compute measures of interrater reliability (including kappa). We quantified the occurances of identified themes in order to identify their relative importance. Descriptive statistics for the quantitative items were computed using Stata 14 (College Station, Texas). The Florida International University Institutional Review Board granted exemption for this study.

All students (n=118) on the family medicine clerkship completed the pregnancy options counseling OSCE; 87% (n=103) answered all quantitative survey questions. Table 1 shows quantitative results.

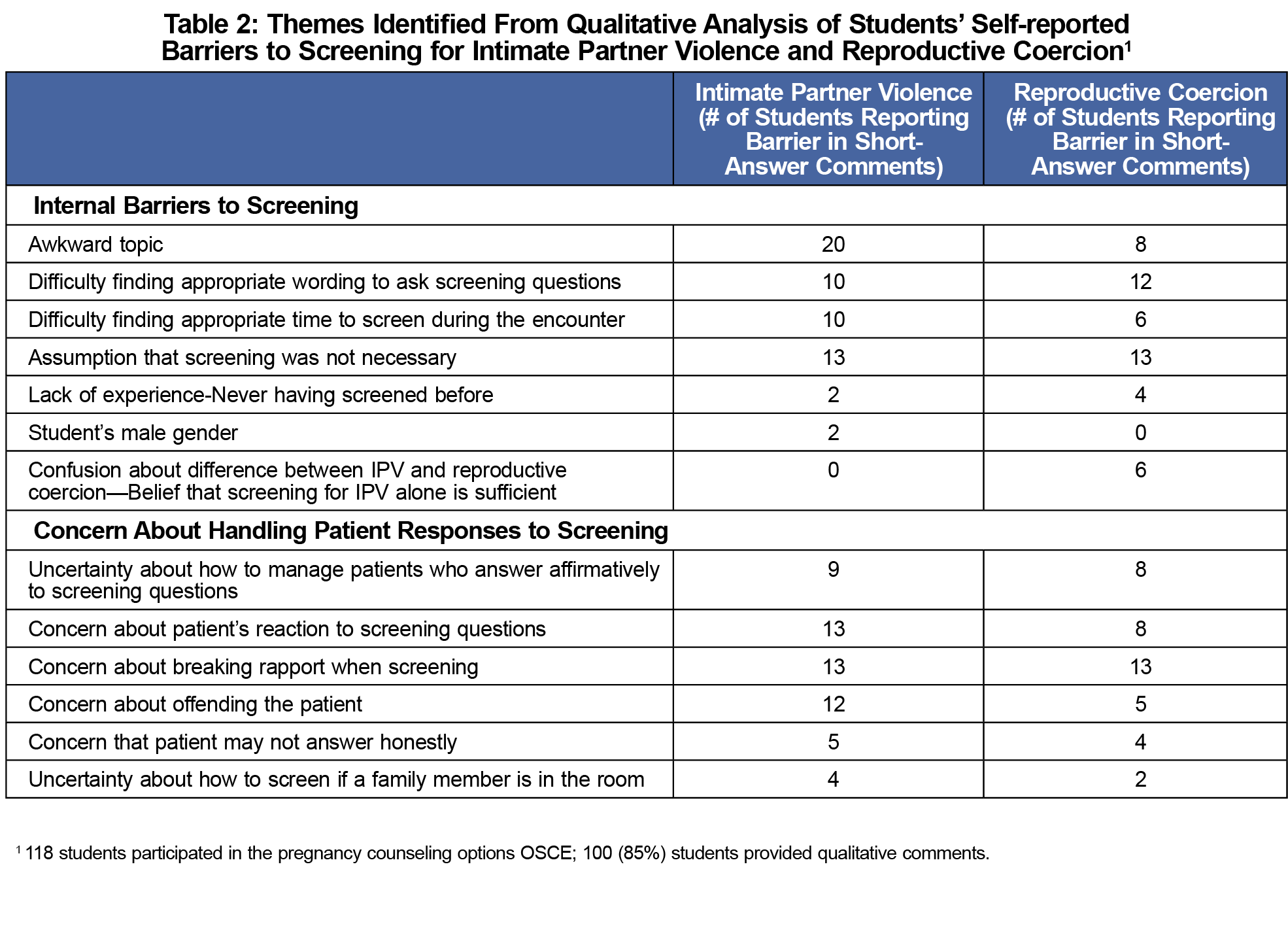

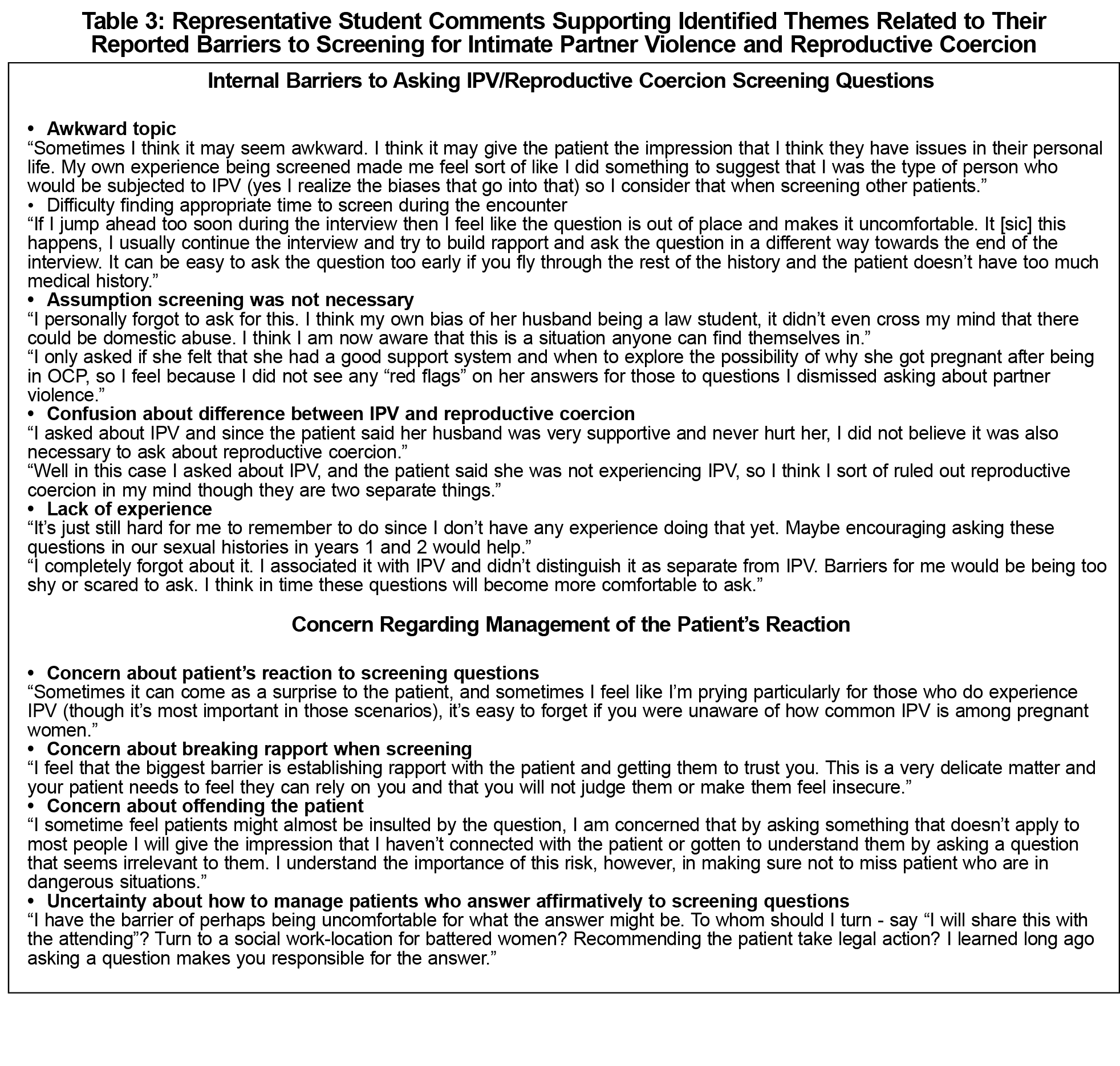

Of the 118 students who completed the OSCE, 100 (85%) provided qualitative comments. Of those, 88 students reported barriers to screening for reproductive coercion, while 12 students explicitly noted no barriers to screening. Ninety students reported a barrier to screening for IPV, while 10 students stated that they had no barriers. The identified themes related to student barriers to screening for IPV and reproductive coercion, along with selected supportive quotes, are reported in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Overall, the kappa coefficient for interrater reliability was moderate at 0.58, and absolute agreement was high at 98%.19

Our findings build on the previous work of Aluko et al by looking at barriers to screening specific to reproductive coercion and by nesting our study within an evaluation of an existing curricular intervention.10 Students reported a variety of barriers to screening for intimate partner violence (IPV) and reproductive coercion that involved both asking the questions and dealing with patients’ potential responses. The reported barriers to screening for IPV and reproductive coercion were similar. Reproductive coercion had the added barriers of confusion about its relationship to IPV and the necessity of screening for it if questions about IPV have already been asked.

Even though the educational module included scripted screening questions, students reported another major barrier to screening was difficulty finding the words with which to ask the questions, thereby suggesting that simply providing scripted questions was insufficient. A taped role-play encounter may be more effective, offering a performance model that can support skills acquisition.20

Many students reported not screening for IPV or reproductive coercion because of their lack of training in how to respond to a positive screen. Our analysis of students’ reported internal barriers suggests that equipping them to provide initial management is an important component of promoting screening behavior. STFM also supports the incorporation of objectives related to both screening and management.11

Our study has several limitations. First, students who found this to be a useful session and a more pertinent or interesting topic may have been more likely to complete the post-OSCE assessment. Another limitation is that students self-reported whether they screened the standardized patient for IPV and reproductive coercion. Ideally, this self-reported data should have been corroborated by the standardized patient’s record of whether a student effectively screened. Due to session logistics, we were unable to incorporate this into the OSCE. Additionally, we performed the study at a single medical school and did not involve a control group of students that was not exposed to the educational intervention being examined. Finally, our study did not allow for long-term follow-up to assess whether students did in fact screen future patients for IPV and reproductive coercion.

Despite these limitations, our preliminary findings support the need for a longitudinal curriculum in IPV and reproductive coercion, during which an appropriate emotional context could be built as a foundation for skills acquisition. This longitudinal approach is also supported by the literature correlating the extent of training with the likelihood to screen.12 Future research should examine the ideal content and structure of curricula addressing IPV and reproductive coercion, and aim to provide more specific correlations between training interventions and screening practices. Additionally, future research should consider the impact of training on long-term IPV and reproductive coercion screening behaviors.

Acknowledgments

Melissa Ward-Peterson is supported by the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities grant (U54MD012393-01) for FIU-RCMI.

Presentations: Stumbar S, Ward-Peterson M, Lupi C. A Pregnancy Options Counseling OSCE in the Family Medicine Clerkship: Educating Students and Exploring Barriers to Screening for Reproductive Coercion and Intimate Partner Violence. Oral Presentation. STFM Annual Conference. Washington, DC. May 2018.

References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Committee Opinion: Intimate Partner Violence. Number 518. February 2012. https://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/Intimate-Partner-Violence. Accessed March 18, 2018.

- Grace KT, Anderson JC. Reproductive Coercion: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2018;19(4):371-390.

- Miller E, Decker MR, McCauley HL, et al. Pregnancy coercion, intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2010;81(4):316-322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2009.12.004

- Phillips SJ, Bennett AH, Hacker MR, Gold M. Reproductive coercion: an under-recognized challenge for primary care patients. Fam Pract. 2016;33(3):286-289. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmw020

- Clark LE, Allen RH, Goyal V, Raker C, Gottlieb AS. Reproductive coercion and co-occurring intimate partner violence in obstetrics and gynecology patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(1):42.e1-42.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2013.09.019

- Thiel de Bocanegra H, Rostovtseva DP, Khera S, Godhwani N. Birth control sabotage and forced sex: experiences reported by women in domestic violence shelters. Violence Against Women. 2010;16(5):601-612. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801210366965

- Gutmanis I, Beynon C, Tutty L, Wathen CN, MacMillan HL. Factors influencing identification of and response to intimate partner violence: a survey of physicians and nurses. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(12):12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-7-12

- Coker AL, Bethea L, Smith PH, Fadden MK, Brandt HM. Missed opportunities: intimate partner violence in family practice settings. Prev Med. 2002;34(4):445-454. https://doi.org/10.1006/pmed.2001.1005

- Sitterding HA, Adera T, Shields-Fobbs E. Spouse/partner violence education as a predictor of screening practices among physicians. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2003;23(1):54-63. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.1340230109

- Aluko OE, Beck KH, Howard DE. Medical students’ beliefs about screening for intimate partner violence. Health Promot Pract. 2015;16(4):540-549. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839915571183

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. National Clerkship Curriculum. https://www.stfm.org/teachingresources/curriculum/nationalclerkshipcurriculum/overview/. Accessed 22 April 2018.

- Buranosky R, Hess R, McNeil MA, Aiken AM, Chang JC. Once is not enough: effective strategies for medical student education on intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. 2012;18(10):1192-1212. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801212465154

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Number of Medical Schools Including Topic in Required Courses and Elective Courses: Domestic Violence/Abuse. https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/cir/406462/06a.html. Accessed March 18, 2018.

- Cohn F, Salmon M, Stobo J; Institute of Medicine Committee on the Training Needs of Health Professionals to Respond to Family Violence. Confronting chronic neglect: the education and training of health professionals on family violence. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. https://www.nap.edu/read/10127/chapter/1. Accessed March 18, 2018.

- Kennedy KM, Vellinga A, Bonner N, Stewart B, McGrath D. How teaching on the care of the victim of sexual violence alters undergraduate medical students’ awareness of the key issues involved in patient care and their attitudes to such patients. J Forensic Leg Med. 2013;20(6):582-587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2013.06.010

- Moskovic CS, Guiton G, Chirra A, et al. Impact of participation in a community-based intimate partner violence prevention program on medical students: a multi-center study. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1043-1047. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0624-y

- Lupi CS, Ward-Peterson M, Castro C. Non-directive pregnancy options counseling: online instructional module, objective structured clinical exam, and rater and standardized patient training materials. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13:10566. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10566

- Lupi C, Ward-Peterson M, Chang W. Advancing non-directive pregnancy options counseling skills: A pilot Study on the use of blended learning with an online module and simulation. Contraception. 2016;94(4):348-352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2016.03.005

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159-174. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529310

- DaRosa D. Teaching Psychomotor Skills: The COACH Model. https://www.scribd.com/document/55876927/Teaching-Psycho-Motor-Skills. Accessed February 11, 2018.

There are no comments for this article.