Introduction: Despite rural origin being a strong predictor of rural practice for health care professionals, rural students face educational barriers and are underrepresented in medical schools. The aim of this study was to identify rural high school students’ perceived barriers to college and health-related careers and compare whether perceptions were similar based on gender, socioeconomic status (SES), and parental education.

Methods: We performed a cross-sectional survey of all high school students from one rural Michigan community. The survey included 13 multiple-choice and 5 short-answer questions. We compared results using χ2 analysis and logistic regression. Free-text answers were grouped thematically and analyzed for patterns.

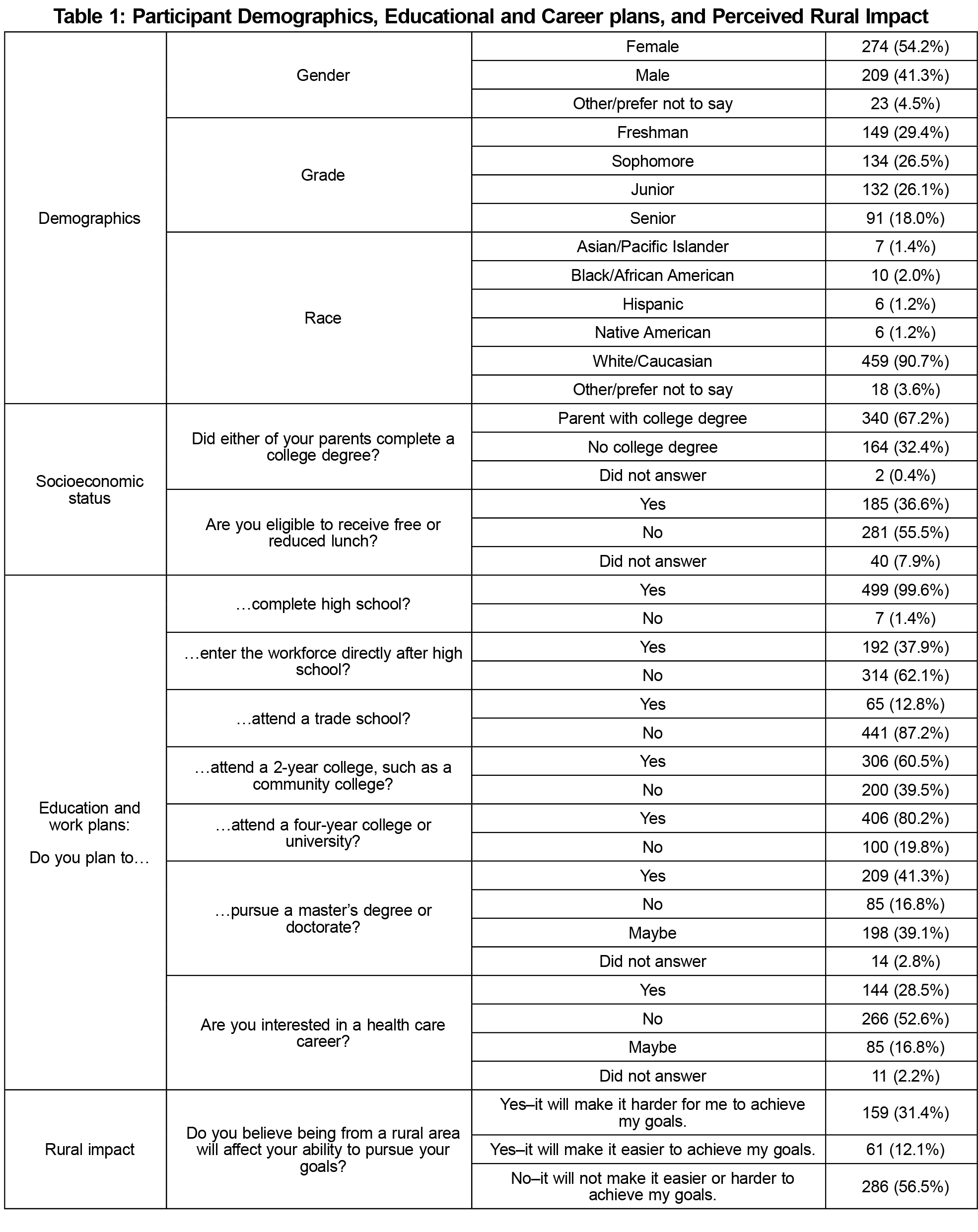

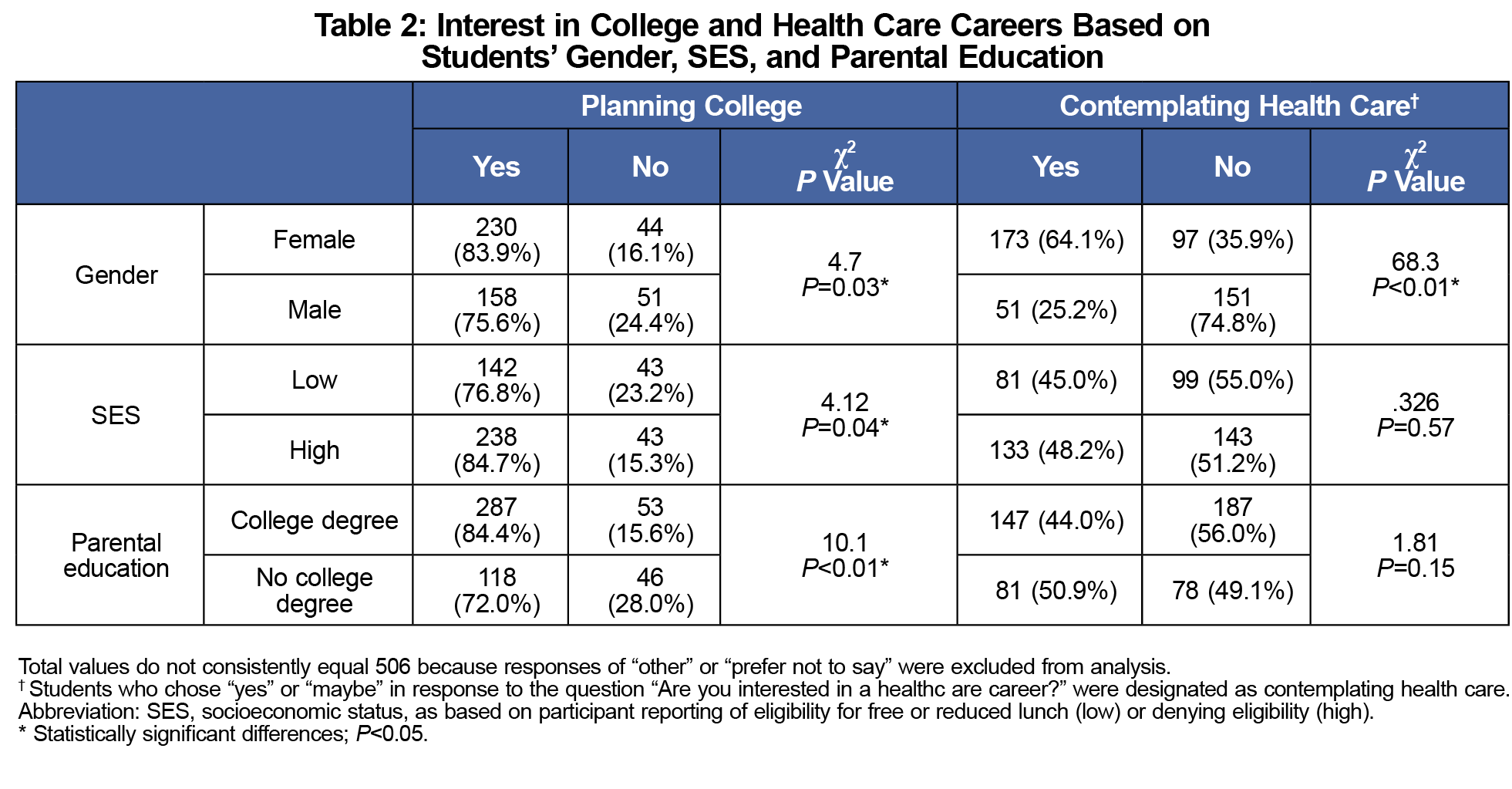

Results: Survey response rate was 97.1% (506/521); 45.3% (229/506) of students were contemplating health care careers. Rural females were more likely to plan on college (females 83.9%, males 75.6%, P=0.03) and to contemplate a health care career (females 64.1%, males 25.2%, P<0.01). Students of lower SES and those who would be first-generation college students were less likely to plan on college (SES: low 76.8%, high 84.7%, P=.04; parental college: yes 84.4%, no 72.0%, P<0.01), although they were equally likely as other students to consider a health care career. Gender and parental education were significant independent predictors of plans for college; female gender was the only significant predictor for health care interest. The most frequently reported barrier to post-high school education was financial, and for health care training, it was academic success.

Conclusions: Rural students are interested in health-related careers. Addressing perceived academic and financial barriers for students from high-need rural communities may inform targeted interventions to increase the rural health care workforce.

Many rural communities face a shortage of health care workers.1 Studies have consistently supported two health care educational interventions: selective admission of rural students, and rural clinical training opportunities, with longer exposure more strongly associated with rural practice.2-7 Despite this evidence, rural students remain underepresented in health professional programs.8-10 This is often due to educational and socioeconomic challenges for these rural students, rather than admission bias.11-14 Rural students are less likely to graduate from high school, less likely to attend college, and much less likely to graduate from college than their peers from urban schools.13,14 This results in a lower proportion of rural students applying to health professional programs, and consequently fewer rural health care workers than would be expected by population demographics.8,9,15

Understanding the barriers rural high school students face may inform pipeline programs and help target interventions to bolster the rural health care workforce. A Canadian study showed that rural students are less likely than urban students to contemplate health care careers,16 with barriers postulated including distance to education, finances, and lack of role models.17,18 An Australian qualitative study supported distance, cost, and insufficient information as barriers.19 However, no studies have explored this issue from the perspective of rural US high school students. The aim of this pilot study was to identify interest in and perceived barriers to higher education and health-related careers, as reported by high school students from an isolated rural community in Michigan.

This cross-sectional study explored rural students’ educational and career goals and perceived educational barriers.The survey included five demographic questions, seven questions about educational and career plans, and one question exploring students' perceptions of the impact of rural upbringing. Students also listed educational barriers using free text.

Alpena, Michigan (population 10,122)20 is the largest population center of Alpena County, a rural county in Northern Michigan.21 Alpena is assigned a Rural Urban Continuum Code of 7 (Nonmetro-Urban population of 2,500 to 19,999, not adjacent to a metro area),22 a Frontier and Remote Area Level 2 (areas where the majority of the population lives 60 minutes or more from urbanized areas,23 and is a medically underserved population.24 A survey was administered anonymously via Google Forms to all students attending Alpena High School from February 3-12, 2017, who did not opt out of participation via a parental consent form. Students had an additional opt-out option on the survey itself.

Data was analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 24. Responses were compared using χ2 and logistic regression, with significance set at P<0.05. Two researchers separately coded free-text quotes and grouped them into themes using immersion and crystallization. Codes and themes were cross checked, and any discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached. Frequency of quotes was compared within each theme through counts of individuals.

The Munson Medical Center Institutional Review Board determined the project was exempt.

Survey response rate was 97.1% (506/521); 274 respondents (54.2%) identified as female, 209 (41.3%) male, and the remaining 23 (4.5%) did not identify as either gender; 459 (90.7%) were Caucasian. The majority planned on attending college (80.2%). See Table 1 for student demographic information and educational/career plans.

Table 2 delineates student interest in a health care career as related to gender, socioeconomic status (as measured by eligibility for free or reduced lunch), and parental education. High school females in our study pool were more likely to plan on attending college and to contemplate a health care career. Students of lower SES and those who would be first-generation college students were less likely to plan on college, although they were equally likely as other students to be considering a health care career. Multivariate logistic regression models were constructed for college plans and health care interest using gender, SES, and parental education as independent variables. Gender and parental education were significant independent predictors of plans for college (female gender odds ratio [OR] 2.0, P<0.01; parental college OR 2.6, P<0.01; full model χ2 [3, N=444]=20.9, P<0.01). With regression modeling of the impact of these three variables on health care interest, gender was the only significant independent predictor (female OR 4.9, P<0.01; full model χ2 [3,N=434]=65.1, P<0.01).

Education/work plans and perception of rural impact were also compared by student class level. There were no significant differences by class level in any education or work plans or in the perception of rural impact, with one exception. Of the four classes, freshman were most likely to respond “yes” or “maybe” to plans for a master’s or doctorate degree (130/145, 89.6%) and seniors were the least likely (64/72, 71.9%; P=0.01).

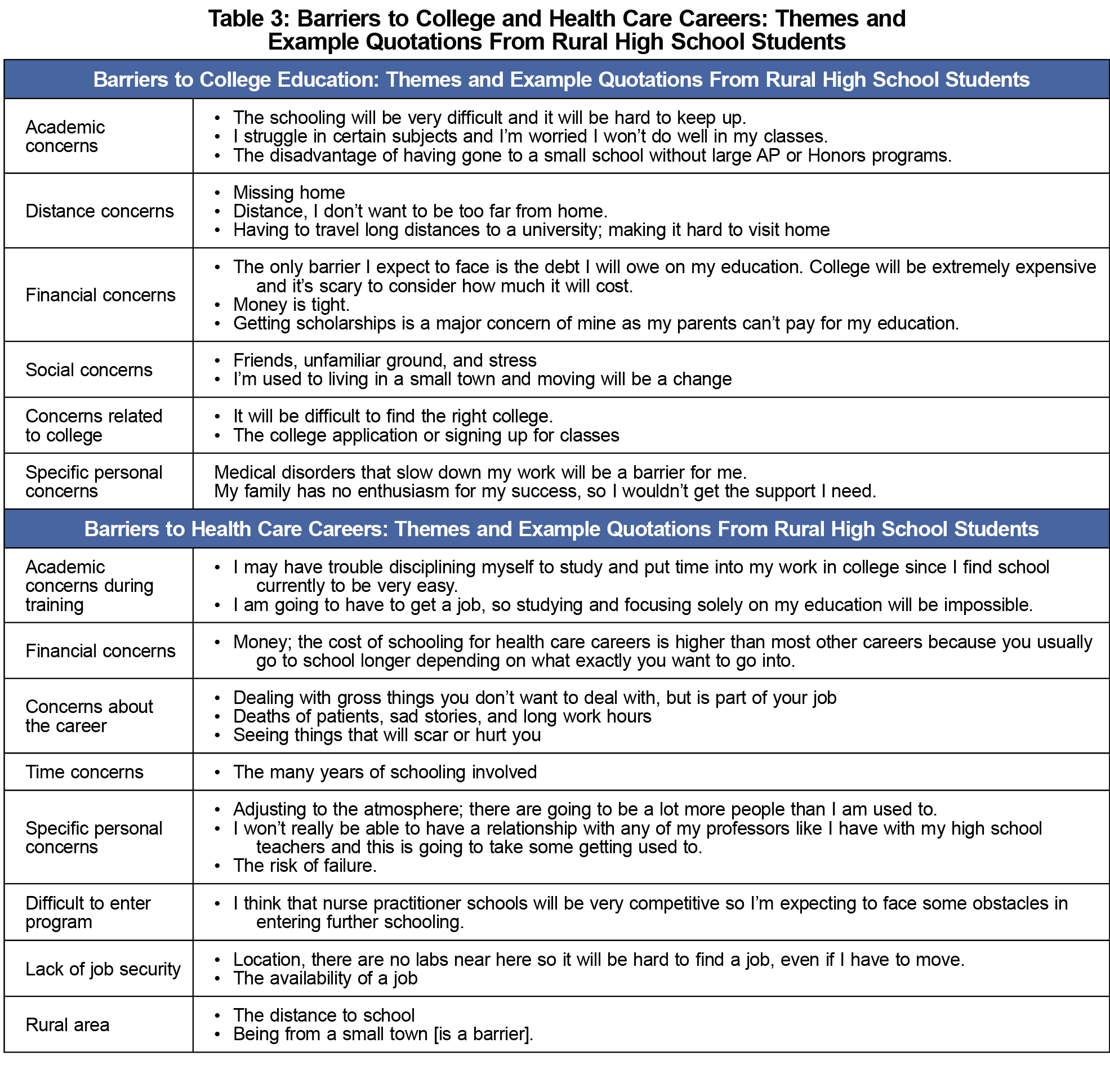

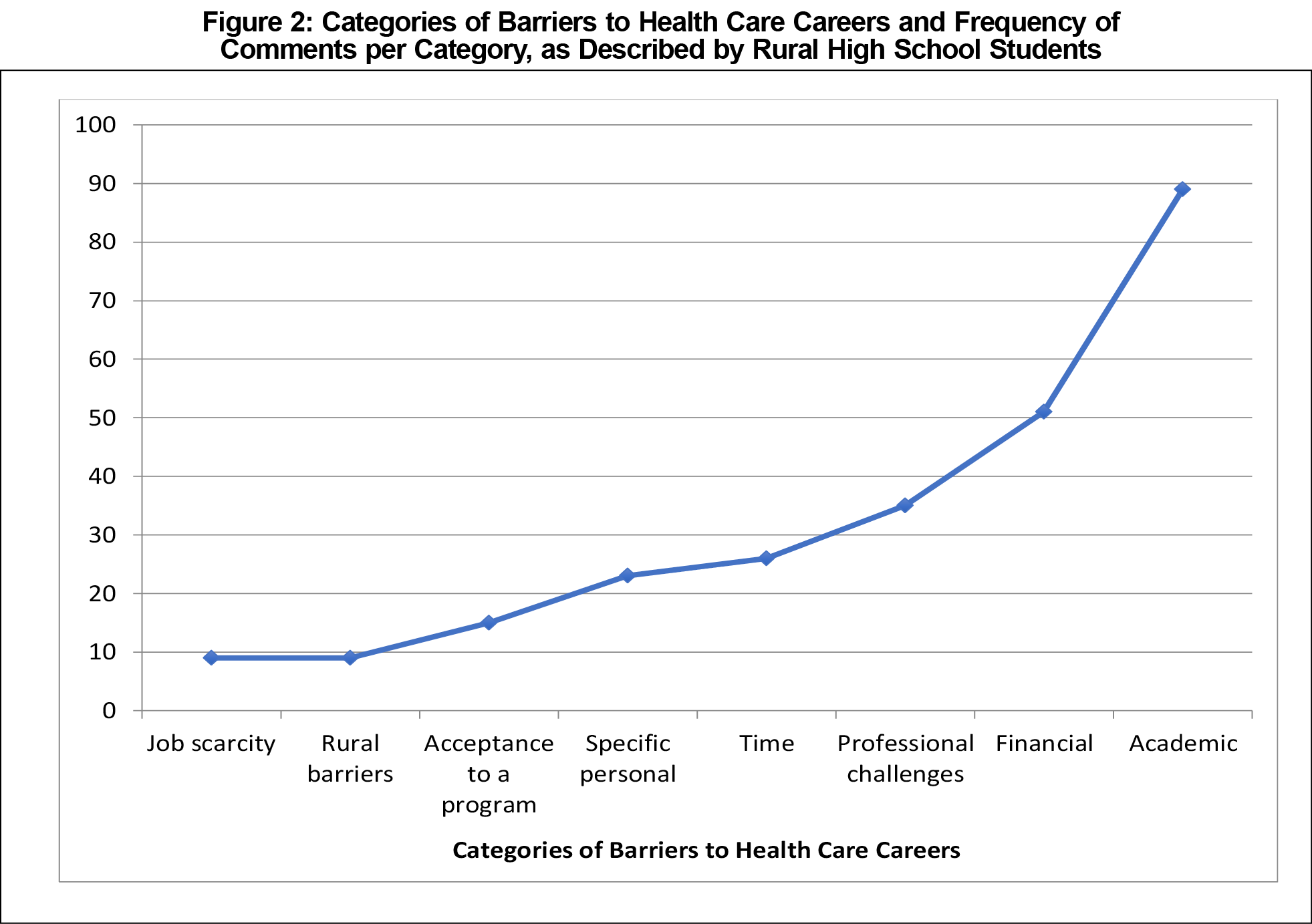

Short-answer responses describing barriers were grouped thematically (Table 3). The most frequently reported perceived barriers to college were financial (Figure 1), while the most frequently reported barriers to pursuing health care careers were academic concerns (Figure 2).

This study of educational goals, health care-related career plans, and barriers as perceived by high school students from a rural county in Michigan shows that although many rural students contemplate college and health care careers, these students anticipate significant barriers including financial, academic, and social concerns. Understanding and addressing these perceived barriers early in rural students’ education may help to alleviate concerns25 and increase the likelihood of college attendance and success.

This study supports previous work demonstrating a relationship between parental education and likelihood of considering college, although SES did not remain a significant predictor—a difference from previous work.14,26 Providing rural high schoolers with mentorship and encouragement—especially for those without family experience with higher education—may be an effective community-based educational strategy to address this initial barrier.

Many rural students’ concerns about college success and health care career training were centered around financial issues, with some eliminating options early because financial concerns were so high. Counseling rural students early in their high school years about need-based educational scholarships and grants, loan repayment opportunities for rural health professionals, and programs such as the National Health Service Corps could potentially address financial concerns.

Students were concerned about their readiness for college studies. Academic concerns could be addressed through guidance counselors and career mentors, who could provide information about academic requirements for various programs. Rural high schools could invite alumni who are successfully attending college, recent college graduates, and those enrolled in health professional programs to speak about their experience to current high school students. Seeing graduates from their own high schools successfully navigating these educational paths may help rural students better visualize their own success.

This study had several limitations, the most important being that only one rural Michigan county was surveyed, limiting generalizability. The survey combined health-related careers when inquiring about interest, limiting information about specific health care paths. The survey also did not provide a definition of “health care career,” which may have affected responses.

Understanding the financial and academic concerns of high school students from high-need rural communities may help inform targeted strategies to address these concerns, and potentially increase medical practitioners in rural communities in the future.

Acknowledgments

Presentations:

- Family Medicine Midwest Conference, October 8, 2017, Rosemont, IL. (Poster Presentation)

- National Rural Health Association Annual Rural Health Conference, May 10, 2017, San Diego, CA. (Poster Presentation)

- Society of Teachers in Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference, May 7, 2017, San Diego, CA. (Poster Presentation)

References

- Doescher MP, Fordyce SM, Skillman SM, Jackson E, Rosenblatt R. Persistent Primary Care Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) and Health Care Access in Rural America. WWAMI Rural Health Research Center, September 2009. http://depts.washington.edu/uwrhrc/uploads/Persistent_HPSAs_PB.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2018.

- Phillips RL, Petterson S, Xierali I, Bazemore A, Teevan B, Bennett K, et al. Specialty and Geographic Distribution of the Phyisician Workforce: What Influences Medical Student and Resident Choices? Washington, DC: Robert Graham Center. http://www.graham-center.org/dam/rgc/documents/publications-reports/monographs-books/Specialty-geography-compressed.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2018.

- Wilson NW, Couper ID, De Vries E, Reid S, Fish T, Marais BJ. A critical review of interventions to redress the inequitable distribution of healthcare professionals to rural and remote areas. Rural Remote Health. 2009;9(2):1060.

- Playford DE, Nicholson A, Riley GJ, Puddey IB. Longitudinal rural clerkships: increased likelihood of more remote rural medical practice following graduation. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0332-3

- Brooks RG, Walsh M, Mardon RE, Lewis M, Clawson A. The roles of nature and nurture in the recruitment and retention of primary care physicians in rural areas: a review of the literature. Acad Med. 2002;77(8):790-798. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200208000-00008

- Ballance D, Kornegay D, Evans P. Factors that influence physicians to practice in rural locations: a review and commentary. J Rural Health. 2009;25(3):276-281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00230.x

- Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, Wortman JR. Medical school programs to increase the rural physician supply: a systematic review and projected impact of widespread replication. Acad Med. 2008;83(3):235-243. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318163789b

- American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2013Academy of Physicians Assistants Annual Survey Report. http://kc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/2013-AAPA-annual-report.pdf. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- US Department of Health and Human Services.The US Nursing Workforce: Trends in Supply and Education. Health Resource and Services Administration. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/pdf/nursing-workforce-nchwa-report-april-2013.pdf. Accessed September 12, 2017.

- Hutten-Czapski P, Pitblado R, Rourke J. Who gets into medical school? Comparison of students from rural and urban backgrounds. Can Fam Physician. 2005;51:1240-1241.

- Basco WT Jr, Gilbert GE, Blue AV. Determining the consequences for rural applicants when additional consideration is discontinued in a medical school admission process. Acad Med. 2002;77(10)(suppl):S20-S22. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200210001-00007

- Hensel JM, Shandling M, Redelmeier DA. Rural medical students at urban medical schools: too few and far between? Open Med. 2007;1(1):e13-e17.

- Byun SY, Meece JL, Irvin MJ. Rural-Nonrural Disparities in Postsecondary Educational Attainment Revisited. Am Educ Res J. 2012;49(3):412-437. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831211416344

- Walpole M. Socioeconomic Status and College: How SES affects college experiences and outcomes Rev Higher Educ.2003;27(1):45-73. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2003.0044

- Doescher MP, Skillman SM, Rosenblatt RA. The Crisis in Rural Primary Care. WWAMI Rural Health Research Center Policy Brief. April 2009. https://depts.washington.edu/uwrhrc/uploads/Rural_Primary_Care_PB_2009.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2017.

- Whalen D, Harris C, Harty C, et al. Should I apply to medical school? High school students and barriers to application. Can J Rural Med. 2016;21(2):46-50.

- Rourke J, Dewar D, Harris K, et al; Task Force of the Society of Rural Physicians of Canada. Strategies to increase the enrollment of students of rural origin in medical school: recommendations from the Society of Rural Physicians of Canada. CMAJ. 2005;172(1):62-65. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.1040879

- Cassidy K, Foster T, Moody E, Turner J, Tejpar S. Perceptions of medical school among high school students in southwestern Ontario. Can J Rural Med. 2013;18(1):7-12.

- Durey A, McNamara B, Larson A. Towards a health career for rural and remote students: cultural and structural barriers influencing choices. Aust J Rural Health. 2003;11(3):145-150. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1584.2003.00481.x

- US Census Bureau QuickFacts. Population Estimates, July 1, 2016. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/alpenacitymichigan,alpenacountymichigan. Accessed November 29, 2017.

- Rural Health Information Hub. Am I Rural? - Report. Alpena, Michigan [search query]. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/am-i-rural. Accessed March 31, 2018.

- United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/. Accessed March 7, 2018.

- US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Frontier and Remote Area Codes. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/frontier-and-remote-area-codes/documentation/. Accessed March 31, 2018.

- Health Resources and Services Administration Data Warehouse. Shortage Areas. https://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov/topics/shortageAreas.aspx. Accessed March 31, 2018.

- Robinson MA, Douglas-Vail MB, Bryce JN, van Zyl TJ. Medical school outreach and mentorship for rural secondary school students: a pilot of the Southwestern Ontario Medical Mentorship Program. Can J Rural Med. 2017;22(2):62-67.

- Astin A, Oseguera L. The declining ‘equity’ of American higher education. The Rev Higher Educ.2004;27(3):321-341. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2004.0001

There are no comments for this article.