Introduction: In response to a government request to address physician shortages in underserved communities, the University of Toronto (U of T) established the Family Medicine Residency Program (FMRP) at the Royal Victoria Regional Health Centre (RVH) in Barrie, Ontario, Canada. Prior to establishing the FMRP, approximately 21% of Barrie residents did not have a family physician. This study investigated residents’ training experiences, strengths and opportunities for improvement of a community FMRP, reasons why graduates choose to work in Barrie after graduation, and graduates’ practice setting and location.

Methods: RVH graduates from 2011-2016 (N=45) were invited to participate. Semistructured one-on-one interviews sought insight into graduates’ experience in the program. We collected online survey data to gather demographic information. We determined current practice location using a government-funded data set and the public registry of the provincial licensing body.

Results: Analysis of qualitative data provided insights into an overwhelmingly positive educational experience that contributed to graduates choosing to stay and work in Barrie. Participants noted the wide range of hands-on training opportunities as a strength of the program. They perceived that the program added value to the local community by increasing capacity to provide care to an underserved patient population. Tracking data demonstrated that two-thirds of graduates continued to work in the RVH region after graduation.

Conclusions: The successful establishment of a new university-affiliated FMRP in an underserved community provides a strong mechanism to recruit physicians. Training in this setting provided excellent educational experiences to residents, who felt prepared to enter independent practice upon completion of training.

In response to a government request to address physician shortages in underserved communities, the University of Toronto (U of T) Department of Family and Community Medicine (DFCM) established a community-based Family Medicine Residency Program (FMRP) at the Royal Victoria Regional Health Centre (RVH) in Barrie, Ontario, Canada in 2009. RVH was one of five community hospitals where the DFCM opened new FMRPs, a process supported by rigorous academic research, affiliation agreements, and strong community investment and engagement.1

RVH is a regional health center located 60 miles north of Toronto. In 2007, prior to establishing the FMRP, the city estimated that 30,000 of its approximately 145,000 residents did not have a family physician. RVH also serves the nearly half million people of the surrounding Simcoe Muskoka region. RVH is part of one of the largest interprofessional family health teams in Ontario, providing primary health care to the community, with 93 family physicians and a roster of approximately 150,000 patients.

Prior to establishment of the FMRP, RVH provided elective opportunities for undergraduate and postgraduate medical learners. Today, RVH provides core family medicine training to 18 residents and 9 to 12 undergraduate clinical clerks per year.

Research has shown that physicians are more likely to settle in communities where they are educated and trained.2-6 Therefore, U of T and RVH viewed the FMRP and the city’s participation in residency training as a strategy for the community to address local physician recruitment needs.

Our research aimed to answer the question “What do the experiences of RVH FMRP graduates suggest for the successful expansion of community-based residency programs in an underserviced community?”

We undertook a multimethods study to explore the experiences of RVH graduates, with the aim of identifying the program’s strengths, distinctive features, and opportunities for improvement. The U of T Research Ethics Board approved the study. As this was a small total cohort, all RVH FMRP graduates from 2011 to 2016 (N=45) were invited to participate.

The study consisted of three parts:

- Online survey data was collected to solicit details of consenting participants' educational background, sociodemographic characteristics, current medical practice, job satisfaction, and future plans.

- We conducted semistructured one-on-one interviews to gain insight into graduates’ experience in the program. We applied principles of purposive, maximum variation sampling to ensure that any potentially significant gaps in the sample would be identified and addressed in the analysis. An independent qualitative researcher (L.R.) conducted this work to mitigate against potential bias. Interviews were digitally recorded for verbatim transcription. L.R. checked all transcripts against the sound files for accuracy and corrected where necessary. Corrected transcripts were entered into HyperResearch software for qualitative data analysis and coded for anticipated and emergent themes. We developed a coding framework, and undertook open, axial, and selective coding iteratively to produce a descriptive, thematic analysis of findings. The analysis used constant comparison, including searches for disconfirming evidence.7,8

The high response rate yielded sufficient variation and there were no concerns about aspects of experience in the program missing from the data. Consistency of responses across the interviews was suggestive of thematic saturation.

- Current practice location was determined using a government-funded data set and the public registry of the provincial licensing body.

Survey Data

Thirty graduates completed the survey:

- The majority (84%) were Canadian medical graduates (CMGs; 81.9% of all Barrie residents were CMGs, as were 83.2% of U of T Greater Toronto Area [GTA] residents).

- Respondents were 62% male (compared to 50% of Barrie residents and 31% of U of T GTA residents).

- Respondents growing up in a small town or rural environment represented 48%, compared to 21% who reported growing up in a large city.

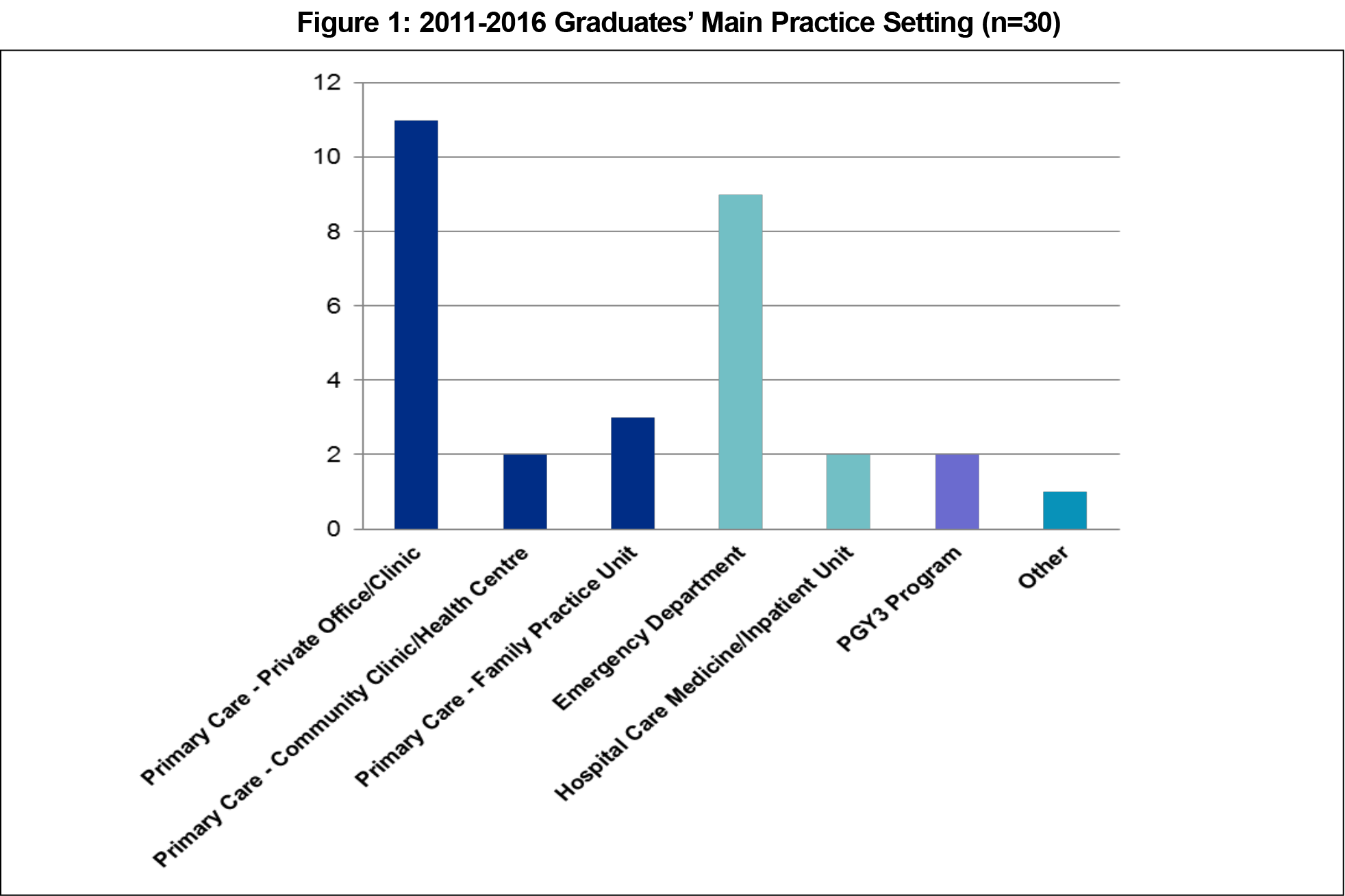

- Comprehensive primary care was being delivered by 53% of graduates; 37% worked primarily in a hospital setting (emergency room, medicine/inpatient unit), and 7% were in advanced family medicine training (Figure 1).

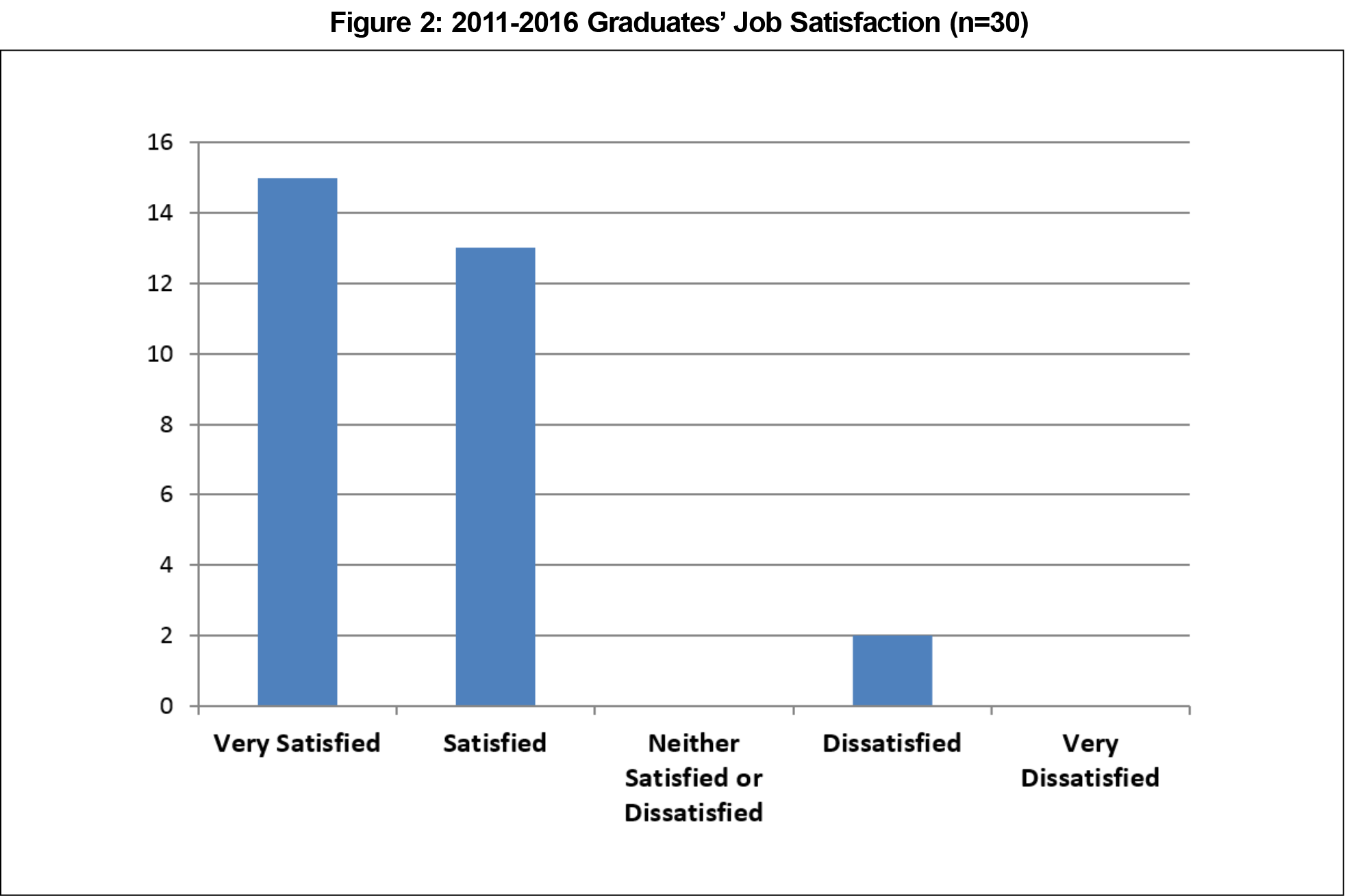

- Job satisfaction was 93% (28/30 satisfied/very satisfied, Figure 2); only 17% indicated that they would very likely change their job setting in the next 5 years.

Qualitative Data

We conducted 19 semistructured telephone interviews:

- Thirteen (68.4%) had been in practice 1 to 5 years, three (15.8%) were new to practice (less than 1 year) and three (15.8%) were in enhanced skills training.

- Seven (36.8%) indicated they worked in Barrie, five (26.3%) worked in Barrie and other locations, six (31.6%) worked in small towns and cities, and one (5.3%) worked in another province.

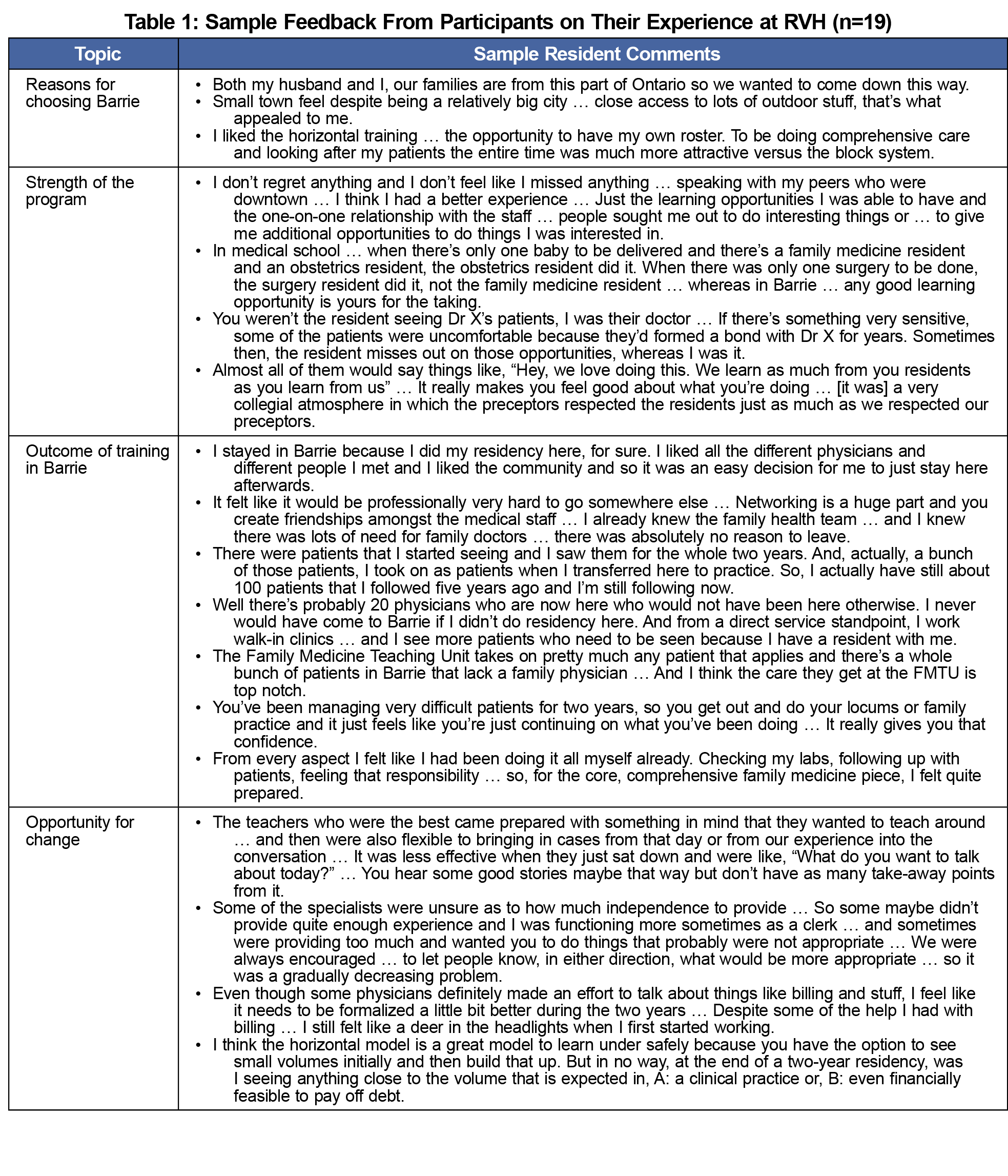

Data analysis provided insights into an overwhelmingly positive educational experience with a wide range of learning opportunities, participants’ reasons for choosing to train in Barrie and/or to stay and practice in Barrie, and some areas were identified for improvement (Table 1).

Reasons for Choosing Barrie

Participants chose to do their residency in Barrie for a variety of pedagogical, geographic, and personal reasons. Many were drawn to the program structure, which gave residents comprehensive responsibility for their own small roster of patients.

One of the things that really attracted me to the program was the horizontal curriculum and the fact that you got your own roster of patients and you followed them throughout the two years.

This aspect of the program was seen as better preparation for independent practice than would be available in a block system where residents see their preceptor’s patients.

Wanting to live in a smaller city and being near family were additional motivations.

Strengths of the Program

Overall, the quality of teaching in the family medicine program was described as consistently high. Strengths of the program included hands-on training opportunities, facilities, and administrative support. The peer group culture in the FMRP was universally seen as cooperative and collegial, with a marked absence of competitiveness.

The Outcome of Training in Barrie

Participants felt extremely welcomed in Barrie, by both the city and the medical community, and most had formed a sense of attachment to the local community. This factored into their decision-making about where to practice postresidency.

I never thought I would live in the Barrie area or stay in the Barrie area and that’s where I’m finding myself now. I think part of it is because I’ve learned the system, learned of the community resources … I feel like it was easy to stay …

They saw the program adding value to the community primarily by increasing the number of physicians to provide care to an underserved patient population.

We have at least 2,000 people that wouldn’t have family doctors otherwise. So I think it’s tremendously helpful to the community.

Many also felt that the program had consolidated their interest in comprehensive family medicine and in working in smaller communities.

Opportunities for Change

While many participants indicated that they hoped the program would retain its essential structure and character in the future, they also identified a number of opportunities for change.

One such opportunity was to achieve greater consistency in the delivery of various aspects of the program, eg, more consistency in preceptors’ approach to end-of-day wrap-up sessions, and more consistency in the quality of off-service specialist rotations.

Another area for improvement related to increasing preparedness for independent practice was provision of more practice management training, and increased patient volumes during residency.

I think the only thing that changed really with independent practice is that the number of patients you see in the day increased. … So going from seeing maybe ten patients a day to, all of a sudden, seeing thirty, was definitely a big leap.

Finally, some welcomed the prospect of an enhanced research and quality improvement culture within the program.

With respect to feedback, one participant noted:

One of the things the program was really great at was our feedback and I feel like a lot of the changes that we had suggested have already been made.

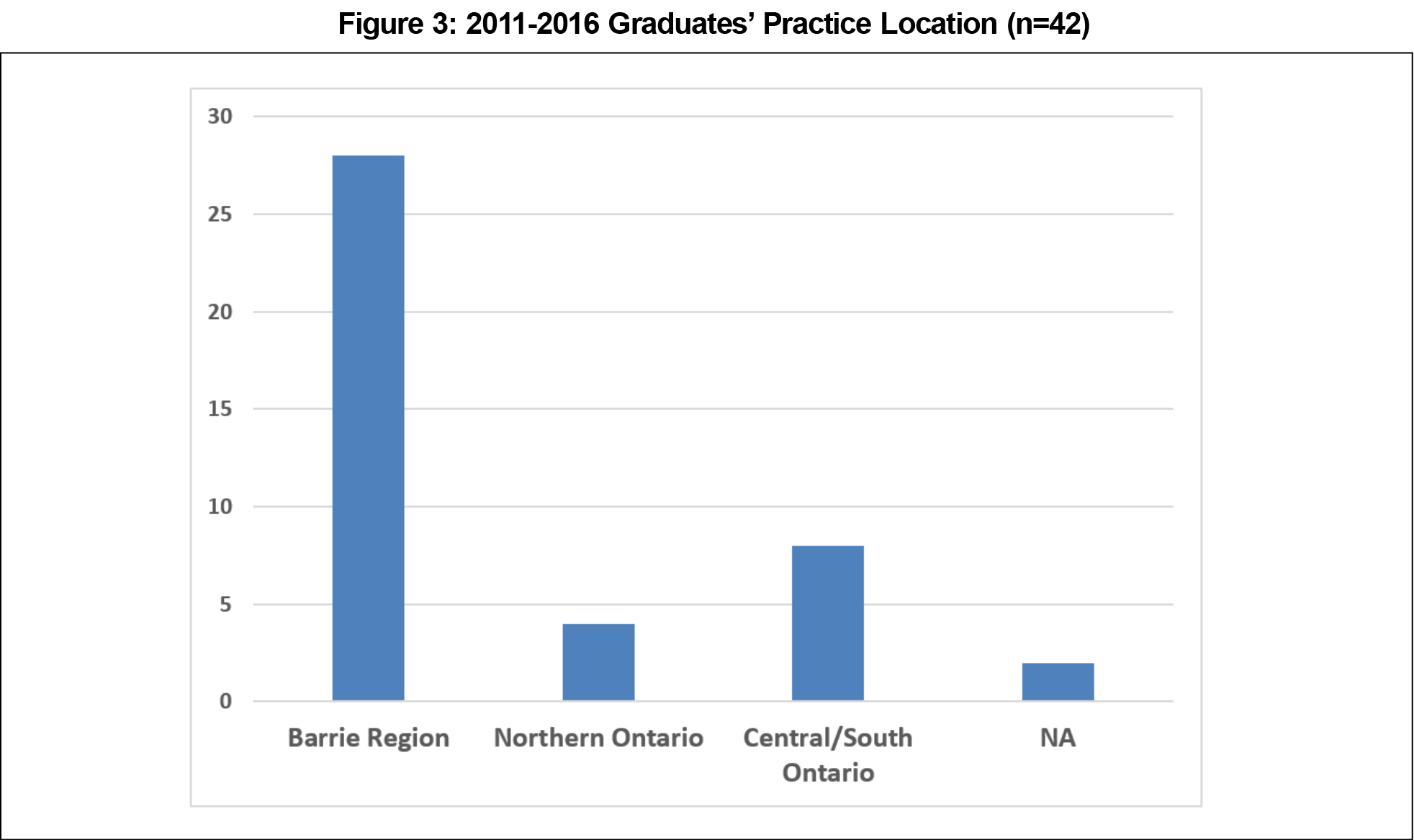

Government Database Information

Tracking data for graduates demonstrated that two-thirds of the RVH graduates (n=42*) continued to work in the RVH region after graduation. In total, three-fourths of the graduates were working in the RVH or another underserved northern region of the province (Figure 3).

The experiences of RVH family medicine graduates suggest that this program has much to offer as a model for the expansion of community-based family medicine programs, in particular the delivery of a horizontal curriculum where residents have their own minipractice and the hands-on experience available in a community hospital across all rotations. The picture that emerged was of a close-knit, collegial environment that offered rich learning opportunities. Interview participants indicated that their experiences in the program were a major factor in their career choice postresidency and they felt prepared for independent practice when they graduated. Feedback from residents, such as about the quality of wrap-up sessions and the need for more practice management training, contributed to important program improvements.

The FMRP was established to help address the physician shortage in Barrie. While we found that some study participants were already connected to the community, others indicated that they decided to stay as a result of their experience. Our administrative data findings suggest that the establishment of the FMRP has been an important physician recruitment strategy as two-thirds of graduates from the first six graduating classes continued to work in the RVH region. In addition, we found that 93% of RVH graduates who completed the survey indicated that they were very satisfied or satisfied with their work.

Our findings suggest that establishment of this community-based FRMP in Barrie provided the opportunity for both residents from the area, as well as others with an interest in living in smaller communities, to experience excellent training in this location and to see their way to establishing a practice there.

A study limitation is that a natural inclination to choose to go to, or stay in, an underserved community may potentially be a more significant recruitment factor than the experience in the program. Our findings do not eliminate the possibility that establishing an unsuccessful program in an underserved community might also help with physician recruitment to that community.

Next steps include longer-term tracking of graduates’ practice location to see whether they stay in Barrie long-term. Our findings suggest that establishing a new community hospital-based FMRP affiliated with an academic university program provides a strong mechanism to recruit physicians and improve access to family physicians in underserved areas. Further studies are needed to build upon these findings.

Footnote

* One of these graduates had transferred out of RVH shortly prior to graduation and two were off-cycle with extended residencies; these three did not show up as graduates in the data set during the study period.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Royal Victoria Regional Health Centre and the University of Toronto Department of Family and Community Medicine for their commitment to community-based family medicine training and their financial support of a qualitative researcher to conduct this study; the University of Toronto Postgraduate Medical Education Office for its physician human resource expertise and data analysis; and the Ministry of Health and Long-term Care for funding and supporting family medicine expansion in Ontario.

Financial Support: This study received financial support from the Royal Victoria Regional Health Centre, and from the University of Toronto Department of Family and Community Medicine.

Presentations:

Canadian Conference on Medical Education, Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada, April 2019 (Poster).

Family Medicine Forum, College of Family Physicians of Canada, Toronto, November 2018 (Presentation).

Association for Medical Education in Europe, Basel, Switzerland, August 2018 (Poster).

Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference, Washington DC, May 2018 (Poster).

References

- Whittaker MK. DFCM New Site Checklist, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto, 2008. STFM Resource Library, General Resource https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/new-site-checklist?CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a. Accessed November 15, 2019.

- Nelson GC, Gruca TS. Determinants of the 5-year retention and rural location of family physicians: results from the Iowa Family Medicine Training Network. Fam Med. 2017;49(6):473-476.

- Fagan EB, Gibbons C, Finnegan SC, et al. Family medicine graduate proximity to their site of training: policy options for improving the distribution of primary care access. Fam Med. 2015;47(2):124-130.

- Strasser R, Hogenbirk JC, Minore B, et al. Transforming health professional education through social accountability: Canada’s Northern Ontario School of Medicine. Med Teach. 2013;35(6):490-496. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2013.774334

- Foley K, Neuberger M, Noel M, Sleight D, vanSchagen J, Wadland W. Advancing geriatrics fellowship programs through a community-based residency network. Fam Med. 2013;45(10):719-725.

- Wheat JR, Leeper JD, Brandon JE, Guin SM, Jackson JR. The rural medical scholars program study: data to inform rural health policy. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(1):93-101. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2011.01.100013

- Sandelowski M. Qualitative analysis: what it is and how to begin. Res Nurs Health. 1995;18(4):371-375. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.4770180411

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

There are no comments for this article.