Introduction: The rural health workforce in the United States is difficult to maintain and harder to increase. This may contribute to worse health outcomes in rural areas and threaten the sustainability of rural hospitals. Previous studies have attempted to identify medical student characteristics and strategies to help grow this workforce. In this study, we aimed to understand the needs of medical students and hospital administrators to identify potential strategies to improve the rural health workforce.

Methods: We conducted medical student and hospital administrator focus groups. We analyzed focus group data separately to identify themes, and reviewed these themes for overlap between groups and potential actionable areas. We calculated Cohen 𝜅 statistics.

Results: We identified 26 themes in the medical student focus groups, and 14 themes in the hospital administrator focus group. Of these themes, three were identical between groups (scope of practice, loan repayment and financial concerns, and exposure to rural health in training), and two were similar between the groups (family and leadership).

Conclusion: The identification of two themes that are similar but not identical between medical students and hospital administrators may serve as part of future strategies to improving rural physician recruitment. Future studies should determine if a shift in language or focus in these areas specifically help to improve the rural health workforce.

People living in rural areas are more likely to report fair to poor health status.1 The age-adjusted death rate is higher in nonmetropolitan areas than metropolitan areas for each of the five leading causes of death in the United States.2 With worse health status and higher death rates, deliberate strengthening of the rural health workforce could be beneficial.

Unfortunately, the rural health workforce continues to shrink. In urban areas there is approximately one primary care physician for every 1,300 people. In contrast, there are over 22 million people living in rural areas who have less than one primary care physician for every 3,500 people.4 Perhaps as a consequence of the decreasing rural workforce, rural hospitals are closing. Between 2013 and 2017, 64 rural hospitals closed, representing a doubling of the previous 5 years.6

Acknowledging the dwindling rural workforce, previous studies have assessed factors that may increase the chance a physician chooses to practice in a rural community. Medical students and residents who have some of their medical training in rural areas are more likely to practice in rural areas.9,10 Most studies focus on the motivations of the student or young physician and note that rural communities should meet these needs. In this study, we aimed to identify the overlap between needs of rural hospitals and students. This overlap might inform potential targets for implementation of strategies to strengthen the rural health workforce in Texas with relatively small shifts from rural communities in order to meet needs of students.

We conducted three focus groups from May 2018 to September 2018. The first two were conducted through email, and included medical students recruited from the University of Texas (UT) Health San Antonio, a school with no rural training track. The third included hospital administrators recruited from a local hospital system with many hospitals set in rural areas throughout Texas.

Twenty-one medical students and hospital administrators participated. There were six female and six male students ranging from first- to fourth-year, and nine administrators. All administrators had experience recruiting physicians to rural hospitals. The UT Health San Antonio Institutional Review Board approved this study (18-140E).

In the student focus groups, a facilitator posed a series of open-ended questions related to their perceptions of rural life and work. The administrator group followed a similar format with questions related to their strategies and experiences recruiting physicians to their rural hospitals. Each lasted 60 to 90 minutes, and was audio recorded and transcribed.

We analyzed transcriptions using an immersion crystallization approach.11 Two reviewers separately examined the transcriptions then met to agree upon identified themes. Each reviewer coded transcriptions independently. We calculated Cohen 𝜅 statistic to assess intercoder reliability (ICR). A 𝜅 below 0.20 indicated no agreement, 0.21 to 0.60 weak agreement, and over 0.60 indicated moderate to strong agreement.12 We conducted analysis using NVivo 12 software (QSR International, Doncaster, Australia).

We identified 26 themes and subthemes from the medical student focus groups, and 14 themes from the administrator focus group. Basic descriptions and examples for the five most common thematic areas identified from the medical student focus groups and hospital administrator focus group are shown in Table 1. The overall average 𝜅 score was 0.53 for the medical student groups and 0.59 for the hospital administrator focus group.

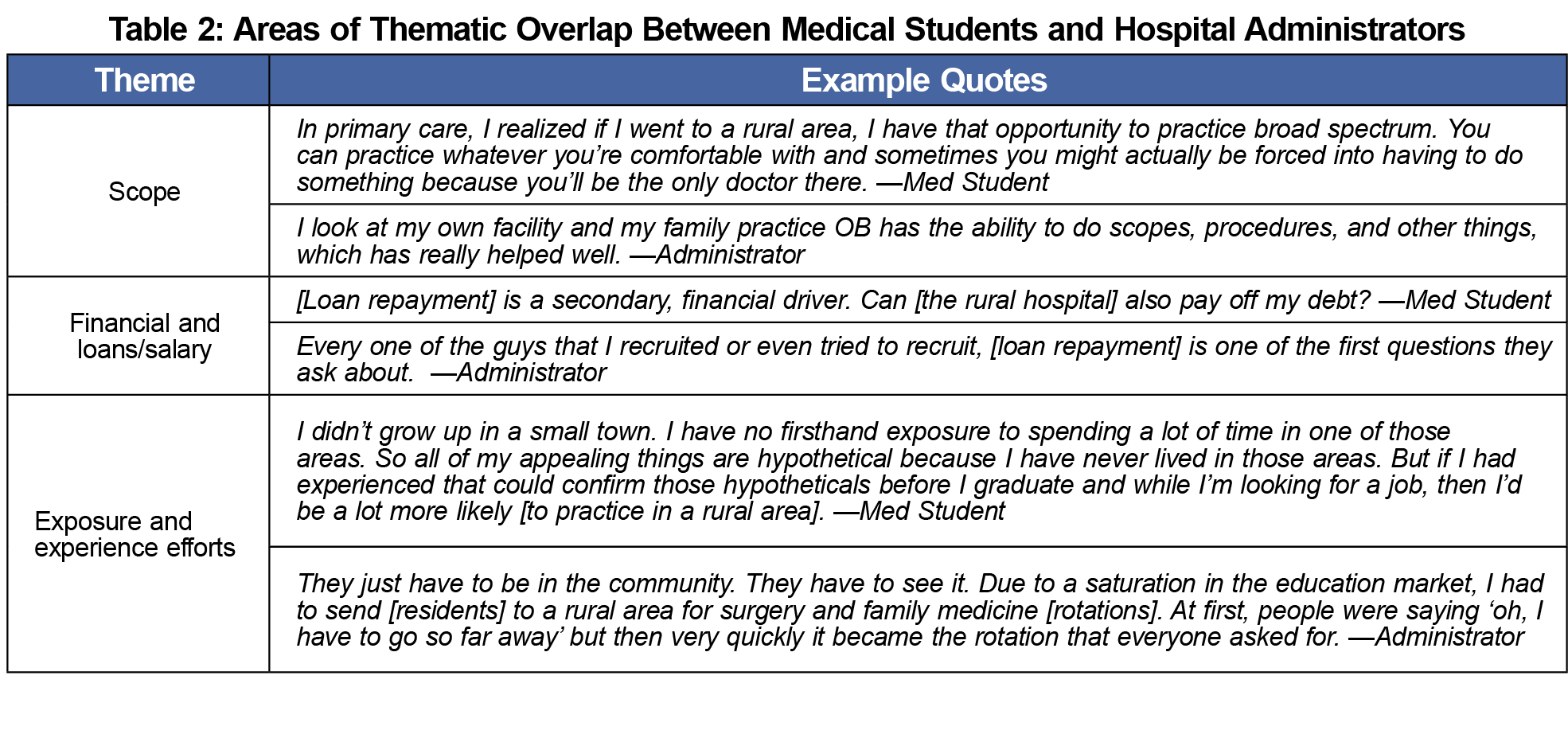

Three themes emerged in both the student and administrator focus groups: scope of practice, loan repayment and financial concerns, and exposure to rural health in training (Table 2). Scope of practice was seen as a positive attribute for both students and administrators. Each of the three themes that emerged in both the student and administrator focus groups were found between 6 and 31 times per group.

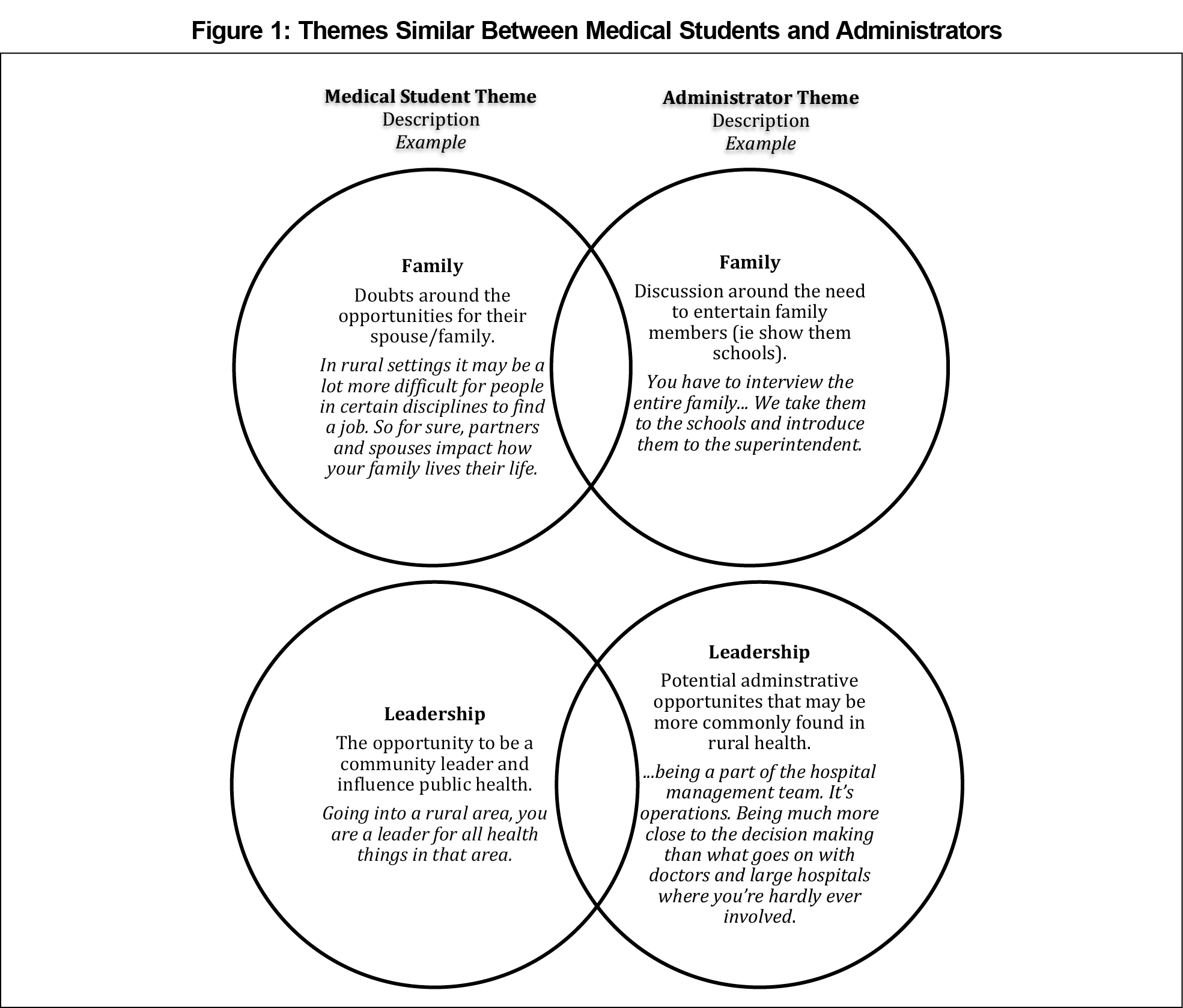

In addition to three themes that emerged in both groups, two themes were similar between the students and administrators (Figure 1). These similar themes were family and leadership.

We aimed to identify the overlap between medical student goals and rural administrator needs in an effort to define strategies to enhance the rural physician workforce in Texas. Both groups understood scope, financial considerations, and exposure to rural health as important, consistent with previously published literature citing these factors (especially exposure to rural health) as critical in recruiting.13,14

The value of exposure to rural health has long been understood. An estimated 76% of rural training track graduates practice in rural areas.15,16 These may be most effective for students already considering rural medicine. Previous studies have recommended admitting more rural students to medical schools because students born in rural areas are 2.4 times more likely to practice in rural areas, and there is a correlation between the decline of acceptance of rural-born students and a decline in interest in rural health.17,18

While intervention at the level of admittance may be best, we found two areas with opportunity to shift the recruiting language to be more attractive to current students. The first is family. Students were concerned about their spouse finding work in their chosen career. Administrators were focused on the need to entertain and sell the social life to the spouse. Strategies to identify creative work solutions for spouses may lead to more successful recruiting.

The second opportunity for shifting language is leadership. Students emphasized the ability to be a leader in public health as a motivator to practice in a rural area. Administrators discussed opportunities for physicians to become leaders through becoming hospital administrators. In rural communities, hospital administrators are likely serving as leaders in public health and other areas, considering hospitals are often the largest employers in rural communities.19 When recruiting, it may be beneficial to clearly associate the opportunity to be involved in hospital administration with the opportunity to be a leader in the community.

Our study has several limitations. First, this is a small study that only begins to understand the overlap between recruiting and medical student goals. Additionally, this includes students at one school without a rural track. These students may be predisposed to certain opinions about rural health. Finally, the study included medical students, not residents. In residency, priorities and perspectives may be different.

Despite these limitations, identifying areas of importance to rural administrators and medical students may inform novel approaches to rural physician recruitment. These approaches should consider focusing on needs of medical students. Persons involved in rural recruitment may consider focusing on leadership opportunities and identifying creative solutions to meeting career needs of physician spouses.

Acknowledgments

Presentation: This study was presented at the NAPCRG Annual Conference, November 19, 2019, in Toronto, Canada.

References

- Burrows E, Ryung S, Hamann D. Health Care Workforce Distribution and Shortage Issues in Rural America. https://www.ruralhealthweb.org/getattachment/Advocate/Policy-Documents/HealthCareWorkforceDistributionandShortageJanuary2012.pdf.aspx?lang=en-US. Washington, DC: National Rural Health Association; January 2012. Accessed August 6, 2019.

- Moy E, Garcia MC, Bastian B, et al. Leading causes of death in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan areas- United States, 1999-2014. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(1):1-8. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6601a1

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, HealthyPeople2 2020. Access to Health Services. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/leading-health-indicators/2020-lhi-topics/Access-to-Health-Services. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Larson E, Johnson K, Norris T, Lishner D, Rosenblatt R, Hart L. State of the Health Workforce in Rural America: Profiles and Comparisons. Seattle, WA: WWAMI Rural Health Research Center, University of Washington, School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine; 2003, https://depts.washington.edu/fammed/rhrc/publications/state-of-the-health-workforce-in-rural-america-profiles-and-comparisons/. Accessed April 23, 2020.

- MacDowell M, Glasser M, Fitts M, Nielsen K, Hunsaker M. A national view of rural health workforce issues in the USA. Rural Remote Health. 2010;10(3):1531.

- US Government Accountability Office. Rural Hospital Closures: Number and Characteristics of Affected Hospitals and Contributing Factors (GAO-18-634). Washington, DC: GAO; 2018. https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-18-634. Accessed August 6, 2019.

- Hung P, Henning-Smith CE, Casey MM, Kozhimannil KB. Access to obstetric services in rural counties still declining, with 9 percent losing services, 2004-14. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(9):1663-1671. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0338

- Hung P, Kozhimannil KB, Casey MM, Moscovice IS. Why are obstetric units in rural hospitals closing their doors? Health Serv Res. 2016;51(4):1546-1560. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12441

- Farmer J, Kenny A, McKinstry C, Huysmans RD. A scoping review of the association between rural medical education and rural practice location. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13(1):27. doi:10.1186/s12960-015-0017-3

- Stenger J, Cashman SB, Savageau JA. The primary care physician workforce in Massachusetts: implications for the workforce in rural, small town America. J Rural Health. 2008;24(4):375-383. doi:10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00184.x

- Miller WL, Crabtree BF. Qualitative analysis: how to begin making sense. Fam Pract Res J. 1994;14(3):289-297.

- Schuster C. A note on the interpretation of weighted kappa and its relations to other rater agreement statistics for metric scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 2014.

- Crump AM, Jeter K, Mullins S, Shadoan A, Ziegler C, Crump WJ. Rural medicine realities: the impact of immersion on urban-based medical students. J Rural Health. 2019;35(1):42-48. doi:10.1111/jrh.12244

- MacQueen IT, Maggard-Gibbons M, Capra G, et al. Recruiting rural healthcare providers today: a systematic review of training program success and determinants of geographic choices. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(2):191-199. doi:10.1007/s11606-017-4210-z

- Rosenthal TC. Outcomes of rural training tracks: a review. J Rural Health. 2000;16(3):213-216. doi:10.1111/j.1748-0361.2000.tb00459.x

- Patterson D, Andrilla C, Schmitz D, Longenecker R, Evans D. Outcomes of Rural-Centric Residency Training to Prepare Family Medicine Physicians for Rural Practice. Seattle, WA: WWAMI Rural Health Research Center, University of Washington, School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine; 2016, http://depts.washington.edu/uwrhrc/uploads/RHRC%20FR113%20Policy%20Brief.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2019.

- Phillips RL, Dodoo MS, Petterson SM, et al. Specialty and geographic distribution of the physician workforce: what influences medical student and resident choices? 2009. http://www.graham-center.org/online/etc/medialib/graham/documents/publications/mongraphs-books/2009/rgcmo-specialty-geographic.Par.0001.File.tmp/Specialty-geography-compressed.pdf. Washington, DC: The Robert Graham Center; 2009. Accessed August, 2020.

- Hyer J, Bazemore AW, Bowman R, Zhang X, Petterson SM, Phillips RL. Medical school expansion: an immediate opportunity to meet rural health care needs. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(2):208.

- Fahe. Transforming Persistent Poverty in America: How Community Development Financial Institutions Drive Economic Opportunity. Partners for Rural Transformation https://fahe.org/wp-content/uploads/Policy-Paper-PRT-FINAL-11-14-19.pdf. Berea, KY: Fahe; 2019. Accessed April 12, 2020.

There are no comments for this article.