Introduction: Medical schools are now required to address health disparities within their curriculum, with a recent emphasis on social determinants of health (SDOH). However, there is scant evidence that incorporating educational experiences around SDOH impacts health equity for patients. The COVID-19 pandemic provided a unique setting to engage students to address SDOH directly with patients.

Methods: The authors designed a service-learning experience in which medical students conducted a patient needs assessment survey by phone to assess SDOH in the domains of health care access, economic stability, and social cohesion. We drew descriptive statistics from a deidentified Excel database of call outcomes to quantify health care interactions and community resource referrals generated by callers.

Results: The call outcomes revealed unmet health and social needs among the patient population and generated a substantial number of actions to improve health care access and awareness of community resources.

Conclusion: The results of this project show that employing medical students to engage with SDOH through action-oriented service learning positively impacts health care access and referrals to community resources. This initiative provides a flexible model to engage medical trainees in addressing health-related social needs that can be applied to a range of clinical settings and learner levels.

The COVID-19 pandemic provided the context for an innovative model of incorporating social determinants of health (SDOH) into medical education at SUNY Downstate College of Medicine in East Flatbush, Brooklyn, New York. When the pandemic resulted in disruption of in-person clinical rotations, medical students generated projects to supplement the strained health care system. East Flatbush was among the hardest hit by COVID-19.6 The resulting health disparities became apparent through early statistics such as hospitalization and mortality rates.7 The pandemic’s effect on chronic health disparities will prove just as dramatic as the population faces decreased access to routine care, long-term economic depression, and increased psychological stressors.

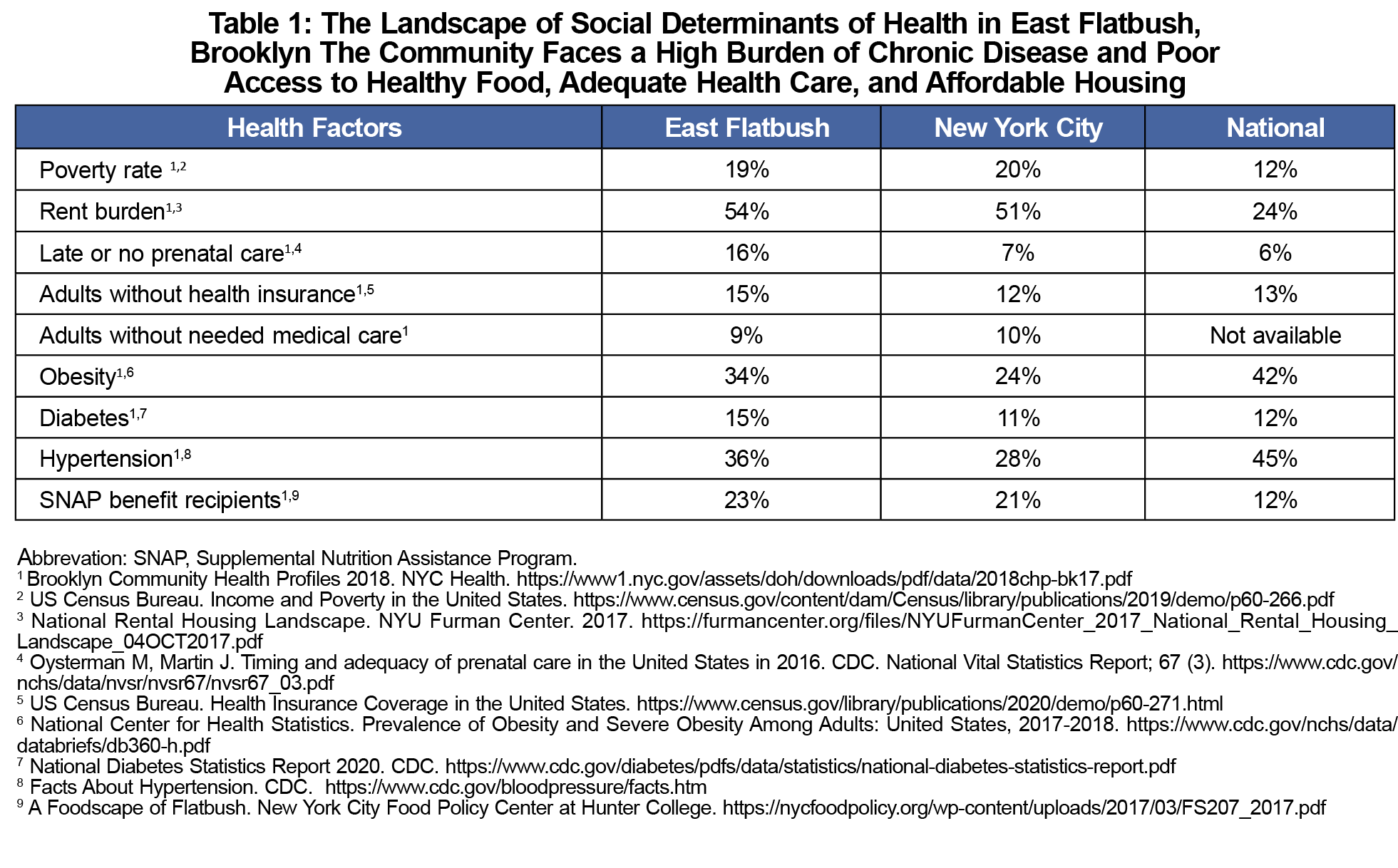

In response to this, students in partnership with faculty developed an SDOH screening tool tailored to the needs of Central Brooklyn patients. The SDOH consist of “conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age,”2 shaped by distribution of resources at the individual, group, and population level. Those factors affecting our Central Brooklyn population are illustrated in Table 1. The Liaison Committee for Medical Education requires that medical education include content on recognizing and addressing the effect of health disparities.1 In this vein, there is a movement to incorporate SDOH into traditional medical curriculum, given their established influence on patient outcomes.2

The aim of this project was to identify and provide resources for unmet health-related social needs among clinic patients, in addition to increasing student competency in addressing SDOH. Callers conducting the SDOH Needs Assessment consisted of both medical student volunteers as well as students enrolled in an associated family and community telemedicine elective. The associated curriculum and learner outcomes are not the primary subject of this study. The existing body of medical education curricula around SDOH remains centered on learned outcomes,3-5 while the focus here is describing a model that centralizes value added to patient care.

Following validated models such as Accountable Health Communities (AHC); Health-Related Social Needs (HRSN); Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences (PRAPARE); and the AAFP Social Needs Screening Tool; students created an outreach protocol tailored to Downstate patients. Our survey tool questions were based on three criteria: high-quality evidence to support their effect, availability of resources to meet the projected need, and the need is unlikely to be addressed otherwise.

Students responded to positive triggers according to an algorithm developed in collaboration with clinical faculty, administrators, and social workers. Callers were provided with remote electronic medical record access to view patients’ medical history. Callers followed a standard protocol to triage clinical concerns, with specific criteria outlined to trigger an appropriate level of response. These responses included immediate contact with a designated clinical preceptor, referral for a telehealth visit within 1 week to 1 month, and emails to providers with refill requests, among others. Patient education regarding COVID precautions followed official recommendations by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Warm remote supervision from an attending was required at all times. Callers documented survey results and subsequent follow-up actions within a shared database. Patients received follow-up calls to assess the outcome of referrals and status of initial needs identified. Total time committed by student callers ranged from 4-15 hours per week, with the highest time commitment required for students enrolled in the associated elective.

To assess the impact of the service-learning experience, we obtained descriptive statistics using deidentified call data from the database of call outcomes. We obtained measures of frequency for given survey responses. This analysis was determined to be exempt from IRB review by IRB#11521 citing exemption # 45 CFR 46.104(d).

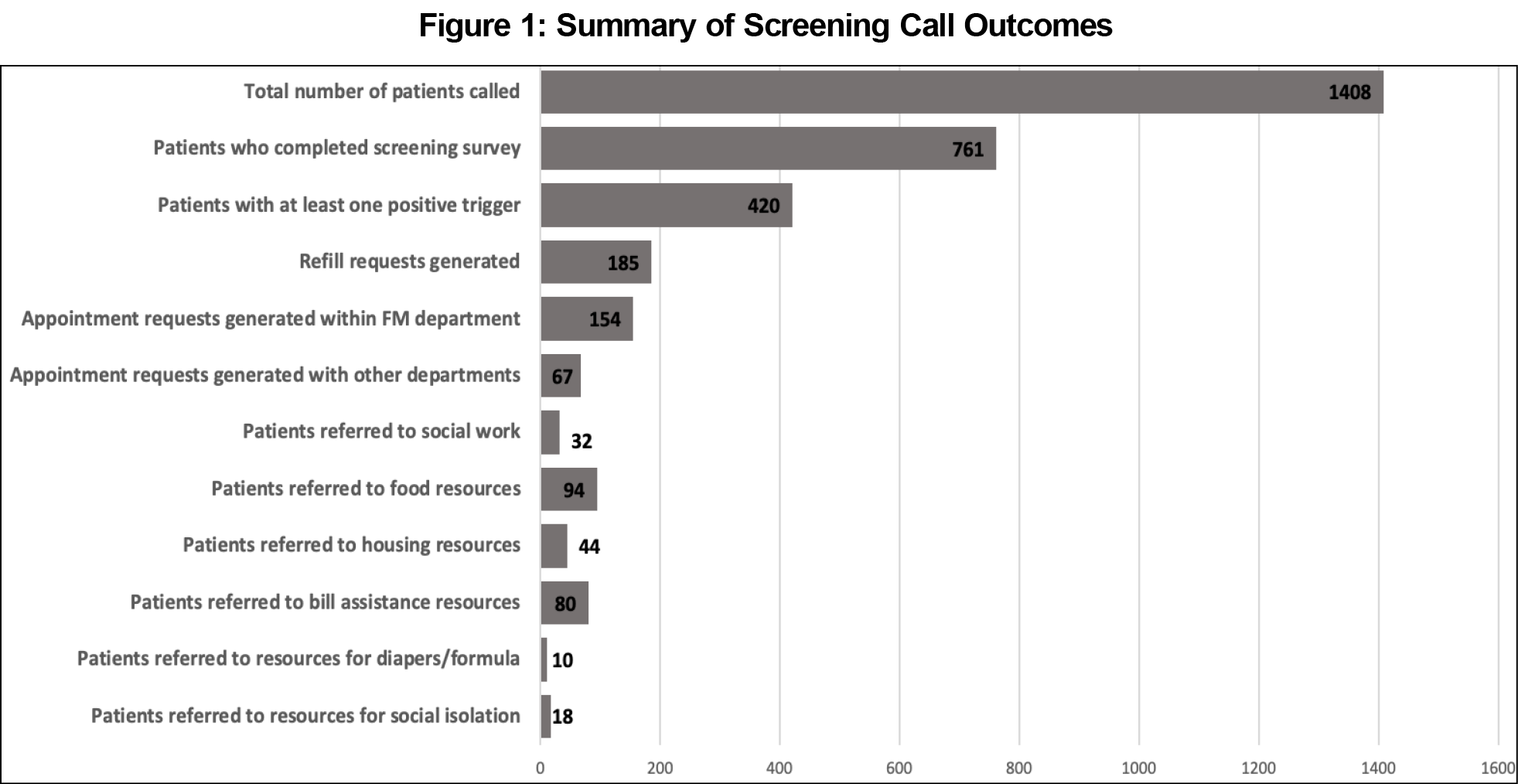

In the first 8 weeks of this initiative, 29 students called a total of 1,408 patients out of a total clinic patient list of 6,519 individuals, with 761 surveys fully completed and 420 calls resulting in at least one positive trigger identified. In response to identified needs, callers generated 32 social work referrals, 185 medication refill requests, 154 appointment requests within the department, and 67 appointment requests with other departments. Additionally, 94 patients were provided with resources for food insecurity, 44 with resources for housing instability, 80 with resources for inability to pay bills, 10 with resources for baby diapers/formula, and 18 with resources for social isolation (Figure 1).

In this descriptive study, we conclude that engaging students in SDOH screening and referrals generated access to health care and social services for patients who otherwise faced disrupted access to hospital resources. Unique to this service-learning model was the centralization of patient needs in addition to learner objectives. We assert that educational activities around SDOH should work toward directly addressing health equity, given the risk of exacerbation of chronic health disparities in the COVID-19 pandemic. The need for support in underserved communities will continue beyond the pandemic, and ongoing evaluation of these needs is critical to the health of our community.

Our pilot study had several limitations. We completed a descriptive analysis of the program, however we did not analyze the needs and resources accessed by patients who were not contacted by students. Anecdotally, many patients reported few alternate outlets to address their health-related social needs during the pandemic. Further research will elucidate the relative effect of this screening and referral intervention compared to the clinic population who did not receive this service.

Despite these limitations, our evaluation shows promise that experiential learning is a feasible model to move medical education around SDOH from passive learning to a generative process that results in meaningful actions in patient care. Our model has since been modified to fit within existing clerkship experiences at our institution. For example, in the women’s health clerkship, the needs assessment has been integrated into the clerkship curriculum and SDOH screening will become a routine part of prenatal care. Academic institutions in similar communities can use this model to ensure they are incorporating social justice within their curriculum for the benefit of both patients and learners.

Acknowledgments

Presentations: This manuscript was presented at the virtual meeting of the Academy of Communication in Healthcare on June 26, 2020.

References

- Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Functions and Structures of a Medical School: Standards for Accreditation of Medical Education Programs Leading to MD Degree (March 2020). https://lcme.org/wp-content/uploads/filebase/standards/2021-22_Functions-and-Structure_2020-03-31.docx. Accessed October 6, 2020.

- World Health Organization. Progressing the Sustainable Development Goals through Health in All Policies: Case studies from around the world (2017). https://www.who.int/social_determinants/publications/Hiap-case-studies-2017/en/. Accessed October 6, 2020.

- Committee on Educating Health Professionals to Address the Social Determinants of Health; Board on Global Health; Institute of Medicine; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. A Framework for Educating Health Professionals to Address the Social Determinants of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press US; 2016 Oct 14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK395983/. Accessed October 6, 2020.

- Doobay-Persaud A, Adler MD, Bartell TR, et al. Teaching the social determinants of health in undergraduate medical education: a scoping review. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(5):720-730. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-04876-0

- Sharma M, Pinto AD, Kumagai AK. Teaching the social determinants of health: a path to equity or a road to nowhere? Acad Med. 2018;93(1):25-30. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001689

- NYC Health. COVID-19: Data Summary. www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data.page. Accessed October 6, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Equity Considerations and Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups. June 4, 2020. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/racial-ethnic-minorities.html. Accessed October 6, 2020.

- Bickerton L, Siegart N, Sola O, Marquez C. SDOH Needs Assessment Phone Script (Word document). June 2020. The STFM Resource Library. https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/sdoh-needs-assessment-phone-script?CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a. Accessed October 6, 2020.

There are no comments for this article.