Introduction: Students participating in longitudinal integrated clerkships (LIC) experience longitudinal, comprehensive care of patients, report improved satisfaction with their training, and express increased interest in pursuing a career in primary care. To gain these benefits without requiring major curricular change, Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine created a year-long mini LIC (mLIC). As participants in the mLIC, we sought to measure our own experiences, gathering data in a systematic way to share our perceptions.

Methods: We developed an online survey that included scale and open-ended questions. Eight students and three cooperating preceptors completed the survey. We analyzed short answer responses thematically; we analyzed multiple choice responses using descriptive statistics.

Results: Participants reported increased interest in underserved rural primary care. Students described the continuity with patients as the most beneficial aspect. Students felt the increased autonomy, self-learning, and hands-on nature of the mLIC increased clinical confidence and preparedness for intern year. Students stated the mLIC provided learning opportunities they would not have experienced in traditional block-based clerkships, including longitudinal relationships and prolonged exposure to primary care. Preceptors stated they were able to learn new ideas from the students and were surprised by how much they benefited from the experience.

Conclusion: Students did experience many of the benefits of a traditional LIC in our mLIC format focused on a longitudinal experience in family medicine. Students and preceptors were positively impacted and felt the mLIC led to increased student learning, professional development, and increased preceptor satisfaction. Our conclusions are limited by the small sample size included in our study.

The shortage of primary care physicians is well documented.1 Longitudinal experiences in primary care can increase student interest in primary care,2 yet few medical schools currently offer such opportunities.3 One way to provide this type of experience is via a longitudinal integrated clerkship (LIC), a curricular structure that enables students to have increased continuity with patients and preceptors, and allows students to perform patient care in a role more similar to that of a physician.4,5 LIC students participate more fully in chronic disease management and directly observe the benefits of continuity in physician-patient relationships.6 The LIC educational model, with principles closely mirroring those of primary care,7,8 improves student satisfaction with their educational experience and increases students’ propensity to specialize in primary care.2, 9-11 The LIC model has motivated preceptors to engage in teaching and has positive effects on general practitioner morale.12 LICs have led to improvements in clinical practice without interfering with administrative, professional, or educational roles.13

Implementing a typical LIC involves transitioning the entire clinical curriculum from traditional block-based rotations to a longitudinal curriculum integrating clinical experiences and rotations throughout the third and fourth year of medical school. Curricular adjustments regularly occur in medical education, but entirely changing a curricular model in medical education is a complex process, involves multiple groups of stakeholders and can take years to plan and implement.14 In an attempt to gain some of the benefits of an LIC without a major curricular shift, the Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine (OU-HCOM) developed a mini LIC (mLIC) consisting of a longitudinal experience in a rural family medicine practice. This mLIC was a unique and novel curricular model, as it enabled students in the program to experience some of the features of an LIC, including management of a patient panel under the same preceptor, in a 1-year program that was integrated within the traditional block-based curriculum at OU-HCOM. In our survey of literature regarding LICs, we were unable to find a similar approach in which elements of an LIC were utilized within a traditional block-based curriculum.

As participants in the mLIC, we sought to measure our own experiences, gathering data in a systematic way in order to share our perceptions as well as those of the other mLIC participants and their preceptors. We hypothesized that the mLIC can provide the same benefits of a traditional LIC in a simpler, more adaptable model.

The OU-HCOM mLIC program occurred during the third year of medical school and has been offered to five students annually since 2017. Participation in the mLIC was voluntary and participants were selected through an application process. The students spent 8 to 10 full weeks with a rural family medicine preceptor as well as an additional one-half day every week or 2 full days bimonthly throughout the academic year. The remainder of the students’ weekly time was dedicated to their traditional third-year rotations. Students followed a panel of 40 to 60 patients, developed a community project, and implemented a quality improvement project in the practice.

We designed a cross-sectional survey-based study. We invited all 11 medical students who completed or were completing the mLIC and all five mLIC preceptors to complete the surveys. Data were collected anonymously during the 2018-2019 academic year. The two student authors (D.B., R.P.) independently sorted responses into categories, then resolved any discrepancies by discussion until consensus. We obtained ethical approval from the Ohio University Institutional Review Board (IRB 17-X-243).

To understand participants’ perceptions of their experiences in the mLIC, we developed and distributed via email an online survey that included scale and open-ended questions. The student survey included six multiple choice, ranking, and open-ended questions. The preceptor survey included six open-ended questions. We summarized the responses to the multiple choice and ranking questions. We reviewed the open-ended responses and grouped them into categories.

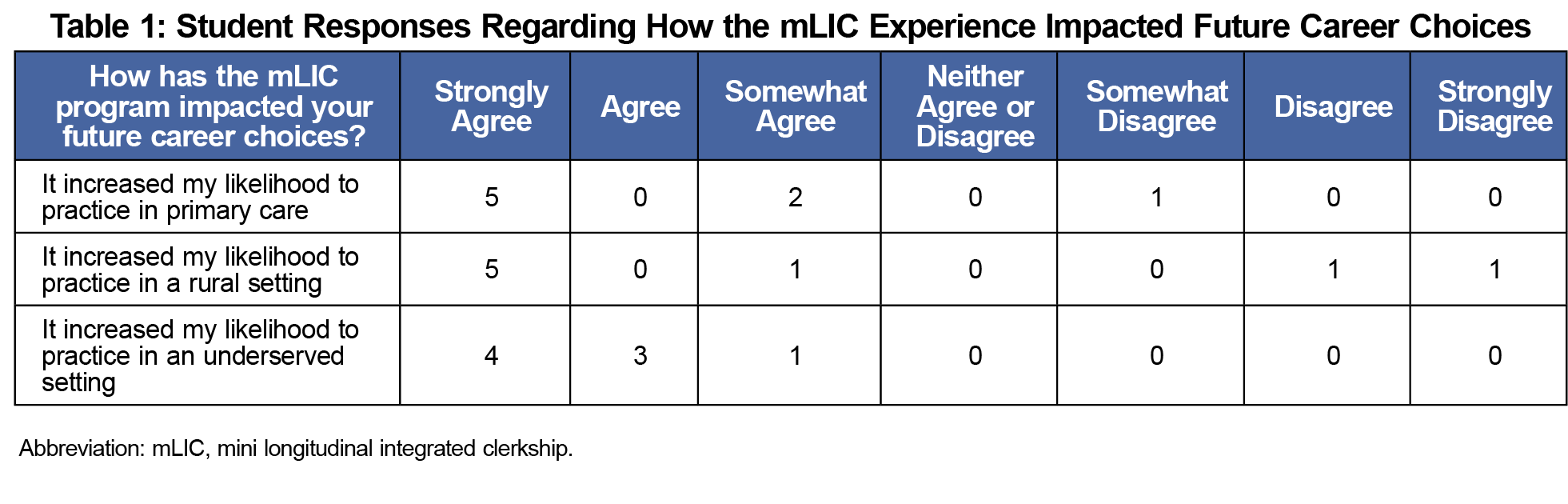

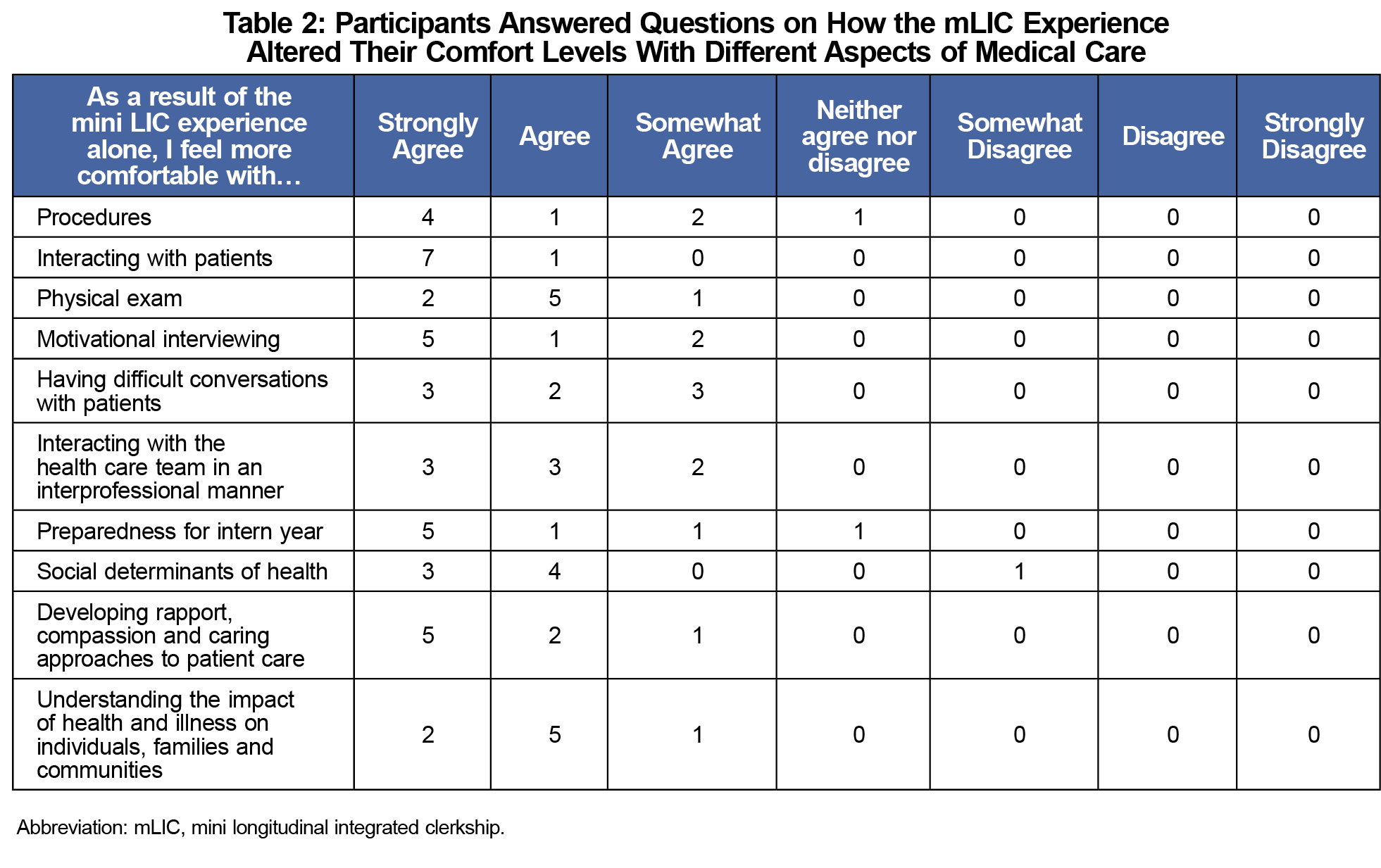

Eight of 11 students who participated in the mLIC completed the multiple-choice survey (Tables 1 and 2); these eight students and three of the five mLIC preceptors answered the open-ended questions. We reviewed the open-ended responses from students and grouped them into three emergent categories: (1) learning through doing, (2) learning enhanced by continuity, and (3) contrasting the mLIC with traditional rotations (Table 3). Students felt that the increased autonomy of the mLIC increased their clinical confidence and preparedness for intern year, as exemplified by the following quotes:

“Having the autonomy of managing 60 patients was an invaluable experience. I feel very confident in my outpatient skills and having any type of conversation with patients.”

“[The mLIC] experience replicated the kind of thinking and independence that will be expected as an intern.”

Students noted that the longitudinal nature of the mLIC allowed them to develop meaningful relationships with patients, learn about chronic disease management, and become more patient centered.

“Having that longitudinal relationship with patients allowed you to get to know the patient beyond the chart, beyond their disease, and get to know them as a person.”

“Once you know the patient, you can spend more time with them, doing medicine. This frees you up to really enjoy the diagnostic, investigative, and clinical decision-making process.”

Students indicated the mLIC provided learning opportunities students would not have experienced in traditional block-based clerkships, including longitudinal relationships and prolonged exposure to primary care.

“Many of the most significant aspects of primary care are a part of the doctor-patient relationship, and it takes observing several visits by the same patient with the same doctor to get a real sense of what that relationship is like. I would not have experienced that without the mLIC program.”

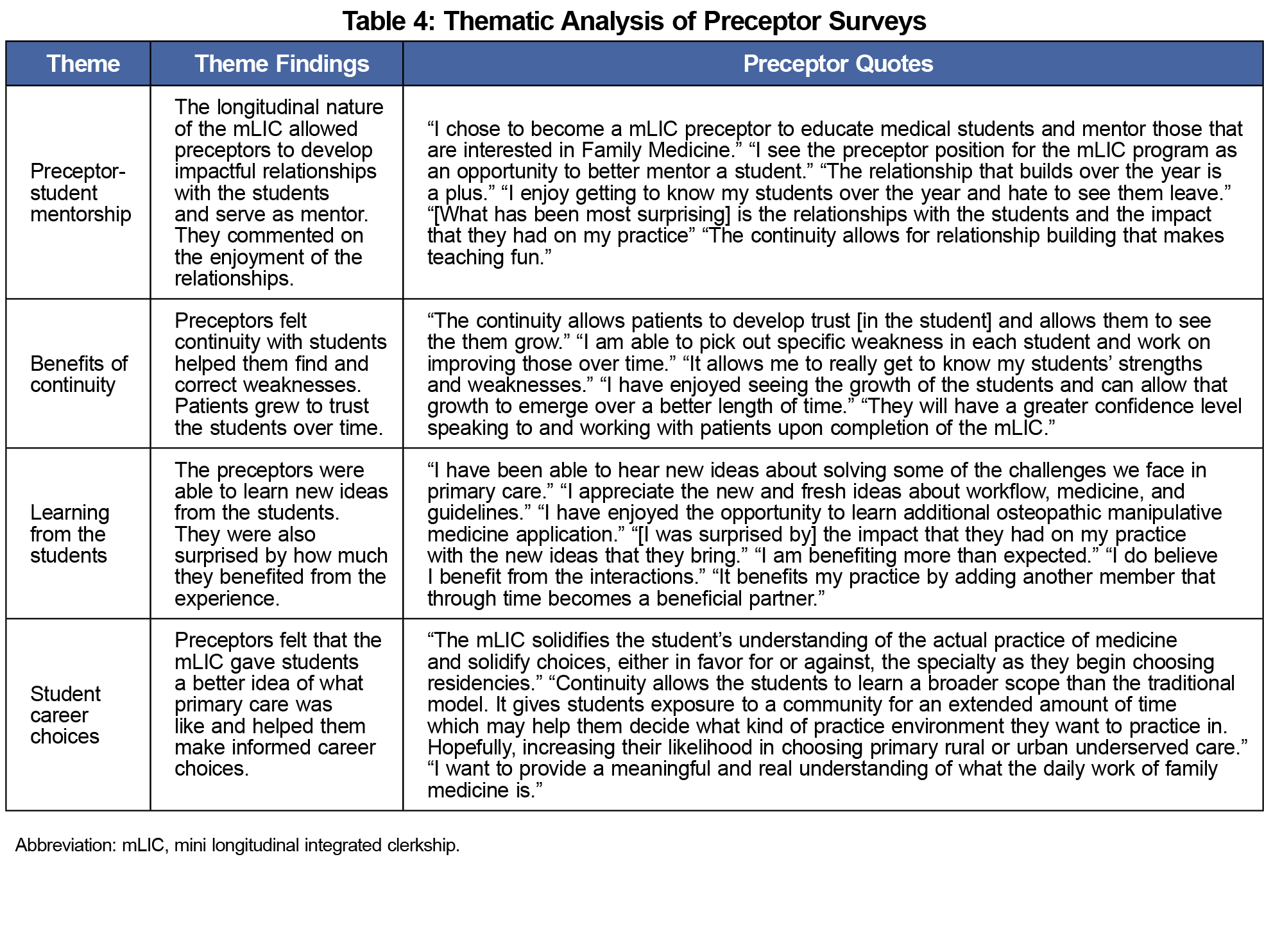

We grouped the preceptor responses into four categories: (1) preceptor-student mentorship, (2) benefits of continuity, (3) learning from the students, and (4) student career choices (Table 4). Preceptors reported that the longitudinal nature of the mLIC allowed them to develop impactful relationships with the students. Preceptors stated that the continuity of the program helped them identify and correct student weaknesses.

“I have enjoyed seeing the growth of the students and can allow that growth to emerge over a better length of time.”

Preceptors felt they were able to learn new ideas from the students and were surprised at how much they benefited from the experience.

“I have been able to hear new ideas about solving some of the challenges we face in primary care.”

Student participants self-reported that the mLIC increased their interest in practicing primary care in a rural, underserved setting. Students stated the increased autonomy in patient care and hands-on experience caused them to feel more comfortable with patient interactions, and increased their confidence in clinical skills and preparedness for intern year. The students cited continuity with patients as a beneficial aspect to the mLIC.

mLIC preceptors felt the length and continuity of the program allowed them to identify and correct student weaknesses and develop mentoring relationships with the students. They were surprised by how much they benefited from the experience and the new ideas the students brought. Preceptors commented that the mLIC gave students a true understanding of primary care.

These findings indicate the mLIC model offers many of the same benefits of the traditional LICs and may increase student interest in primary care. Without requiring a large curricular transition, the mLIC created longitudinal opportunities similar to a traditional LIC that may not have happened in traditional block-based rotations.

This study was intentionally limited to the participants in the mLIC, which was already a small number. Participation was voluntary and the response rate was less than 100%, making selection and response bias a serious limitation. Further understanding of the utility of mLICs could be gained by larger studies at OU-HCOM as more students complete the mLIC.

Acknowledgments

Conflict Disclosure: The authors of this manuscript were also participants in the mLIC program described in this study.

References

- New Findings Confirm Predictions on Physician Shortage [press release]. www.aamc.org/news-insights/press-releases/new-findings-confirm-predictions-physician-shortage. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; April 23, 2019.

- Pfarrwaller E, Sommer J, Chung C, et al. Impact of interventions to increase the proportion of medical students choosing a primary care career: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(9):1349-1358. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3372-9

- Williams MP, Agana DF, Rooks BJ, et al. Primary care tracks in medical schools. PRiMER Peer-Rev Rep Med Educ Res. 2019;3:3. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2019.799272

- Hauer KE, Hirsh D, Ma I, et al. The role of role: learning in longitudinal integrated and traditional block clerkships. Med Educ. 2012;46(7):698-710. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04285.x

- O’Brien BC, Poncelet AN, Hansen L, et al. Students’ workplace learning in two clerkship models: a multi-site observational study. Med Educ. 2012;46(6):613-624. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04271.x

- Hirsh DA, Ogur B, Thibault GE, Cox M. “Continuity” as an organizing principle for clinical education reform. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(8):858-866. doi:10.1056/NEJMsb061660

- Bodenheimer T. Primary care—will it survive? N Engl J Med. 2006;355(9):861-864. doi:10.1056/NEJMp068155

- Starfield B. Primary Care: Concept, Evaluation, and Policy. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992.

- Norris TE, Schaad DC, DeWitt D, Ogur B, Hunt DD; Consortium of Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships. Longitudinal integrated clerkships for medical students: an innovation adopted by medical schools in Australia, Canada, South Africa, and the United States. Acad Med. 2009;84(7):902-907. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a85776

- Hirsh D, Walters L, Poncelet AN. Better learning, better doctors, better delivery system: possibilities from a case study of longitudinal integrated clerkships. Med Teach. 2012;34(7):548-554. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2012.696745

- Poncelet AN, Mazotti LA, Blumberg B, Wamsley MA, Grennan T, Shore WB. Creating a longitudinal integrated clerkship with mutual benefits for an academic medical center and a community health system. Perm J. 2014;18(2):50-56. doi:10.7812/TPP/13-137

- Hudson JN, Weston KM, Farmer EA. Engaging rural preceptors in new longitudinal community clerkships during workforce shortage: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:103. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-12-103

- Tabb Z, Monteiro K, George P. Preceptor expectations and experiences in a longitudinal integrated clerkship. PRiMER Peer-Rev Rep Med Educ Res. 2018;2:3. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2018.824638

- Velthuis, Floor MSc; Varpio, Lara PhD; Helmich, Esther MD, PhD; Dekker, Hanke PhD; Jaarsma, A. Debbie C. DVM, PhD Navigating the complexities of undergraduate medical curriculum change: change leaders’ perspectives. Acad Med. October 2018;93(10) 1503-1510 doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002165

There are no comments for this article.