Introduction: Home visits can improve quality of care and health outcomes and provide a unique opportunity to learn more about patients’ social context and assess patients’ various social determinants of health (SDH). The objectives of this study were to assess patient self-reported SDH, resident reflections on patient social status, the utility of a SDH survey during home visits, and resident comfort levels addressing patient SDH.

Methods: This was a mixed-methods pilot study utilizing patient self-reported data and open-ended reflection questions. Participants included adult patients aged more than 18 years from an urban safety-net clinic and family medicine residents who provide their care.

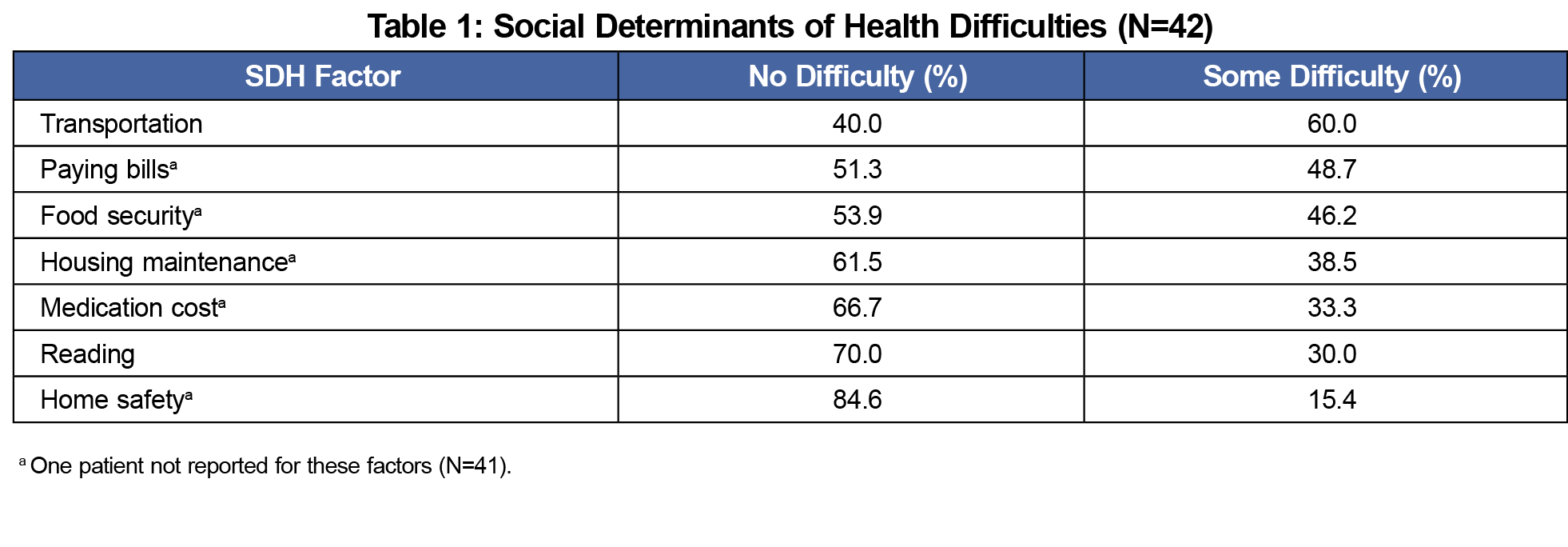

Results: We received forty-two surveys from 42 home visits. Most patients were female (61.9%) and African-American (45.2%), aged from 25 to 88 years (mean=60.24). Top patient-reported SDH include transportation, paying bills, and food insecurity. Common themes of resident responses included positive utility of the survey for assessing patient SDH; variation in comfort level when inquiring about patient SDH with positive influence from prior experience, assistance from colleagues, or prior good relations with patients; and expressed intention to include SDH assessment in future practice.

Conclusions: Residents recognized the value of assessing SDH during home visits and expressed intent to include it in future practice. Thorough assessment of patient SDH may help to craft a more robust and standardized system to prioritize patients who would most benefit from receiving home visits.

Currently most patient care, and hence medical training, occurs within established clinical settings.1-3 This is far removed from the horse-and-buggy style of medicine wherein physicians treated patients in their own homes.1,4,5 Although medical home visits significantly declined throughout much of the 20th century, they are still viewed both as meaningful forms of clinical practice and as valuable settings for medical education.1,6,7 Indeed, physicians made 478,088 house calls to Medicare beneficiaries in 2000, doubling to 995,294 house calls in 2006.8 However, while the overall number of home visits increased during this time, most were performed by specific types of physicians, for example geriatricians, osteopaths or those in rural practice.1,8

One cited benefit of home visits includes hot-spotting, the process of identifying individual high-utilizers of medical services, patients who often have complicated social factors negatively influencing their health.3,9 Conversely home visits may also be useful for cold-spotting, which involves identifying communities with complex social determinants of health (SDH) and limited primary care access with the intention of bridging primary and public health care in a population.3,10 Such strategies recognize the importance of identifying and assessing the impact of patients’ SDH in order to improve overall biopsychosocial health and reduce health disparities.11 While this assessment can be done in a formal clinical setting, home visits uniquely offer clinicians the advantage of direct access to the context of a patient’s life circumstances, allowing for more comprehensive strategies to improve patient health and quality of life.3,12,13

Until 2014, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) mandated family medicine residents conduct home visits as part of their educational requirements.3 Though literature on this is limited, one previous study showed that family medicine residents expressed positive impressions of home visits for older patients because the experience gave them better insight into their patients’ lives, helping to improve their caregiving and assessment skills.7 Considering the potential benefits of addressing SDH in the context of patients’ homes, the Department of Family and Community Medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center continues conducting resident-led home visits, despite the withdrawn ACGME requirements. This study was initiated in 2017 with the purpose of analyzing the SDH of those home visit patients as well as residents’ perceptions of the experience.

This mixed-methods pilot study utilized both patient self-reported quantitative data and resident responses to qualitative self-reflection questions. The patient questionnaire was an abridged SDH survey derived from several sources including a geriatric SDH inventory.14-16 The resident conducting the home visit read and recorded patient responses to the survey items that also served as a guide to inform an SDH-focused patient history. We assessed patient SDH factors, including transportation, paying bills, food security, housing maintenance, medication cost, legal problems, finances, employment security, reading, and personal and home safety. Patient answers were Likert-scaled using the following possible responses, “no difficulty at all,” “some difficulty,” “very difficult,” and “completely difficult.” During analysis, we created a binary Likert scale (no difficulty, some difficulty).

After each home visit, residents completed an open-ended questionnaire consisting of five questions that assessed their views on the visit and the effects of discussing SDH with patients. Residents were asked about the effectiveness of using the survey as a guide for assessing and understanding patient SDH. They were also asked how comfortable they felt about the discussion with the patient and what they were able to learn about their patient from the experience that they might not have otherwise. Finally, the residents were asked to predict how they might take any lessons learned and implement them into their future practices.

Resident responses to the open-ended questions were entered into an Excel spreadsheet and were grouped according to the relevant survey questions. Two authors (P.D. and M.C.) independently reviewed the data through a process of open content analysis, an approach utilized to derive categories and patterns directly from textual data.22 Reflections and analytical notes were compared and utilized in a further iteration of data analysis to achieve consistency and derive patterns from the responses. These findings were shared, and further refined with the other project members (N.G. and P.P.). Once consensus was achieved, the group performed a final review of the responses to ensure accuracy, consistency, and prevalence across the data.

All current adult patients of the Parkland Family Medicine Residency Clinic, an urban, safety-net, teaching clinic that provides care to a medically underserved population in Dallas, Texas, were eligible to participate and were selected by the resident physician based on perceived need. Accompanied by a physician assistant, residents conducted the home visits with clinic standard of care addressing health needs in addition to the SDH questionnaire. This study was approved by the UT Southwestern Medical Center Institutional Review Board and the Parkland Hospital and Health System Office of Research Administration.

From September 2017 to June 2019, 26 family medicine residents conducted 42 home visits. Resident participants were primarily female (54%) and spanned all 3 years of family medicine postgraduate training: 35% were first-year, 42% second-year, and 23% third-year residents. Patients received one home visit each. Patients ranged in age from 25-88 years old (mean age=60.24) and were primarily female (61.9%); 45.2% of patients identified as African-American, 21.4% Hispanic/Latino, 14.3% Caucasian, and 19.1% selected “another ethnicity.” Four patients were currently employed and 25 were on a fixed income. Patient responses to SDH difficulties are described in Table 1. We developed themes from resident responses and subsequently reanalyzed for prevalence across home visits. Percentages following each theme indicate the prevalence of these responses across resident participants. Key patterns in resident responses and supporting quotes are shown in Table 2.

Despite the ACGME removing home visits requirements, our study shows that home visits provide meaningful opportunities to teach residents about patient health in a holistic fashion. Study results also indicate that patient participants must overcome a variety of difficulties to maintain their biopsychosocial well-being. Results show that approximately half of the patients in this study struggled with transportation, paying bills, food security, and housing maintenance, among others. Additional studies underscore opportunities to identify SDH difficulties in the primary care setting and point to a more general need to improve identification and amelioration of SDH obstacles that patients face.17-21 While this study included a relatively small sample size, the results show that residents learned more about their patients, gained novel insights into patients’ psychosocial health, and in general found the survey to be a useful guide for conducting an otherwise sensitive conversation. This is consistent with a previous study showing family medicine residents giving positive feedback on the home visit experience, helping improve their ability to care for and understand their patients and their life circumstances.7 This pilot study demonstrates the need for future studies that apply more rigorous assessment of the educational outcomes of resident-led home visits and measure the impact of the home visit on subsequent clinic encounters.

References

- Kao H, Conant R, Soriano T, McCormick W. The past, present, and future of house calls. Clin Geriatr Med. 2009;25(1):19-34, v. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2008.10.005

- Starr P. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. Reprint ed. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1982.

- Sairenji T, Wilson SA, D’Amico F, Peterson LE. Training Family Medicine Residents to Perform Home Visits: A CERA Survey. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(1):90-96. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-16-00249.1

- Walkinshaw E. Back to black bag and horse-and-buggy medicine. CMAJ. 2011;183(16):1829-1830. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-3995

- Saunders S. A horse-and-buggy kind of doctor. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60(8):739-740.

- Perkel RL, Silenzio VM, Kairys MZ. A house call program as an essential component of primary care training. Prim Care. 1996;23(1):47-65. doi:10.1016/S0095-4543(05)70260-8

- Laditka SB, Fischer M, Mathews KB, Sadlik JM, Warfel ME. There’s no place like home: evaluating family medicine residents’ training in home care. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2002;21(2):1-17. doi:10.1300/J027v21n02_01

- Peterson LE, Landers SH, Bazemore A. Trends in physician house calls to Medicare beneficiaries. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(6):862-868. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2012.06.120046

- Gawande A. The hot spotters: can we lower medical costs by giving the neediest patients better care? New Yorker. 2011;40-51.

- Westfall JM. Cold-spotting: linking primary care and public health to create communities of solution. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(3):239-240. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2013.03.130094

- Healthy People 2020. Social Determinants of Health. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion website. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health. Accessed April 25, 2018.

- Dattalo M, Nothelle S, Tackett S, et al. Frontline account: targeting hot spotters in an internal medicine residency clinic. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(9):1305-1307. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-2861-6

- Pimlott N. Whither the housecall? Can Fam Physician. 2013;59(3):234.

- Levy H. Income, Poverty, and Material Hardship Among Older Americans. RSF. 2015;1(1):55-77. doi:10.7758/rsf.2015.1.1.04

- Unwin BK, Jerant AF. The home visit. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60(5):1481-1488.

- Unwin BK, Tatum PE III. House calls. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(8):925-938.

- Walker RJ, Gebregziabher M, Martin-Harris B, Egede LE. Relationship between social determinants of health and processes and outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes: validation of a conceptual framework. BMC Endocr Disord. 2014;14:82. doi:10.1186/1472-6823-14-82

- Pinto AD, Bloch G. Framework for building primary care capacity to address the social determinants of health. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63(11):e476-e482.

- DeVoe JE, Bazemore AW, Cottrell EK, et al. Perspectives in Primary Care: A Conceptual Framework and Path for Integrating Social Determinants of Health Into Primary Care Practice. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(2):104-108. doi:10.1370/afm.1903

- LaForge K, Gold R, Cottrell E, et al. How 6 Organizations Developed Tools and Processes for Social Determinants of Health Screening in Primary Care: an Overview. J Ambul Care Manage. 2018;41(1):2-14. doi:10.1097/JAC.0000000000000221

- Braveman P, Egerter S, Williams DR. The social determinants of health: coming of age. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32(1):381-398. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101218

- Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277-1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

There are no comments for this article.