Introduction: Women’s health is only briefly explored in the preclerkship medical curriculum. Volunteering in student-run free clinics (SRFCs) increases clinical confidence; such service learning could bridge the gap between limited curricular offerings and student desire for exposure to women’s health topics. This study aimed to identify weaknesses in the women’s health preclerkship curriculum, build an educational intervention, and explore SRFCs as a teaching tool.

Methods: We performed chart review of SRFC female patients to evaluate care. We held student focus groups to elicit feedback about the established curriculum. Based on this information, we devised a workshop to review practical skills. Participants attended the workshop, volunteered at SRFC, and completed surveys preintervention and at 3 months postintervention. A control group completed baseline and follow-up surveys.

Results: We invited all 151 second-year students to participate; six attended the workshop and 21 served as control. There were no baseline differences between groups regarding age, prior experience with women’s health, confidence in relevant skills, and subjective readiness for clinical rotations; the control group had more men. After the workshop, intervention participants reported increased confidence in women’s health-related skills and in readiness for the OB/GYN rotation. Gains persisted at 3 months. Three of six students in the workshop group volunteered at SRFC; three of 12 in the control group volunteered.

Conclusions: The addition of an interactive workshop to the existing preclinical curriculum on women’s health has lasting impact on subjective readiness for clinical clerkships. SRFC may be a useful addition to classroom learning. This initiative is student-led and reproducible, and could serve as an adjunct to established preclerkship curriculum.

At US allopathic medical schools, issues pertinent to women’s health are briefly discussed in the preclerkship curriculum. Women’s health issues carry significance across specialties, most notably in primary care and obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN). Less than half of schools feature preclerkship conversations about contraception and elective abortion; senior students from 101 medical schools reported brief-to-moderate curricular coverage of women’s health.1,2

Brief interventions for preclerkship medical students have been effective. An optional 1-week senior student-run sexual health selective increased knowledge of sexual health topics, while a 1-day training session improved student confidence in women’s primary care.4,5

The student-run free clinic (SRFC) may bridge the gap between limited curricular time and student desire for exposure. SRFC volunteering has been associated with increased clinical confidence and could support confidence in women’s health.6

The objective of this study was to identify needs in the curriculum related to women’s health, design an intervention to complement participation in SRFC, and evaluate the impact of this intervention.

Analysis

To identify care already provided at SRFC and exposure afforded to students, electronic chart review assessed demographic and clinical factors of all female patients who presented for care before April 1, 2018. Patients were excluded if they were aged less than 18 years, or more than 70 years (to create a cohort of nonelderly adult women); had their last clinic visit before January 1, 2013 (to ensure that care was representative of current practices); and/or only one clinic visit.

We held focus groups of preclerkship and senior-level students to elicit feedback about the women’s health curriculum and service learning opportunities. All members of the first-year class and of the third- and fourth-year classes were invited to participate in the preclerkship and senior-level groups, respectively. Questions and discussion topics were composed in advance, and the same senior student facilitated both sessions; dinner was provided as incentive for participation. Audio recordings were transcribed and reviewed by two independent researchers using content analysis, and coding was compared. We performed separate analysis of the groups, and we compared themes between year levels to evaluate change over the course of medical education.

Design, Development, and Implementation

Building upon identified weaknesses, we devised a 3-hour women’s health workshop. Education level was targeted for rising second-year medical students. We encouraged participants to volunteer at SRFC with female patients at least once during the semester.

Evaluation

Participants completed a preintervention survey 1 week prior to didactic sessions and a postworkshop survey immediately following to assess learning, confidence, and subjective readiness for OB/GYN and primary care rotations. A control group of peers also completed baseline survey. Workshop and control group participants completed 3-month follow-up surveys immediately prior to the start of clinical rotations.

We collected survey data using Qualtrics online software. Variables were compared with descriptive statistics. We utilized two-sample Student t test to analyze difference between continuous variables, and performed Fisher exact test to compare categorical variables. We determined statistical significance using α of 0.01 to reduce Type I error. All statistical analyses were univariate and performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software. The Columbia University Irving Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this research.

Analysis

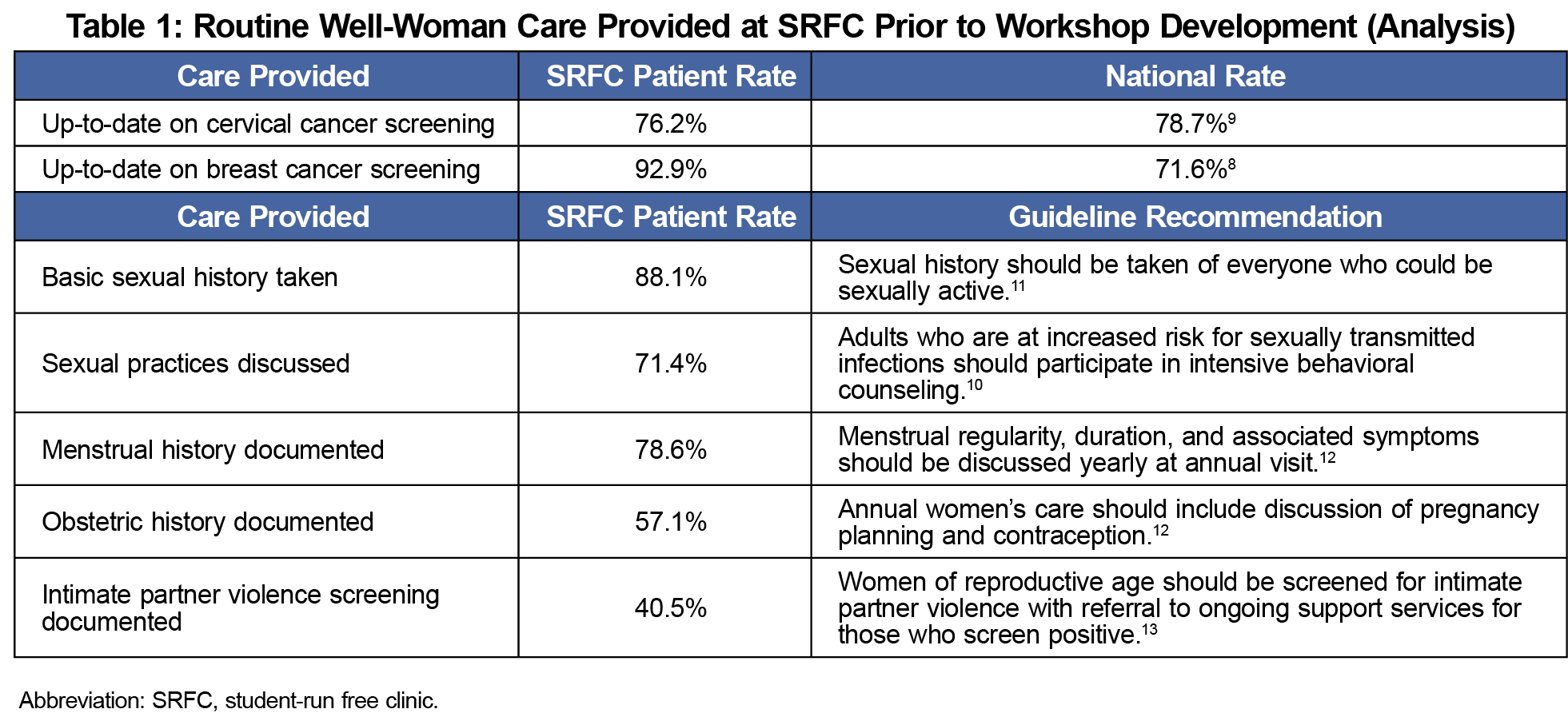

We identified 89 SRFC female patients, and we reviewed data for a cohort of 42 women ages 26-70 years (mean 57, median 58). Rates of documented well-woman care are shown in Table 1; review demonstrated that the majority of patients had documentation of a basic sexual history, cervical cancer screening, and breast cancer screening.

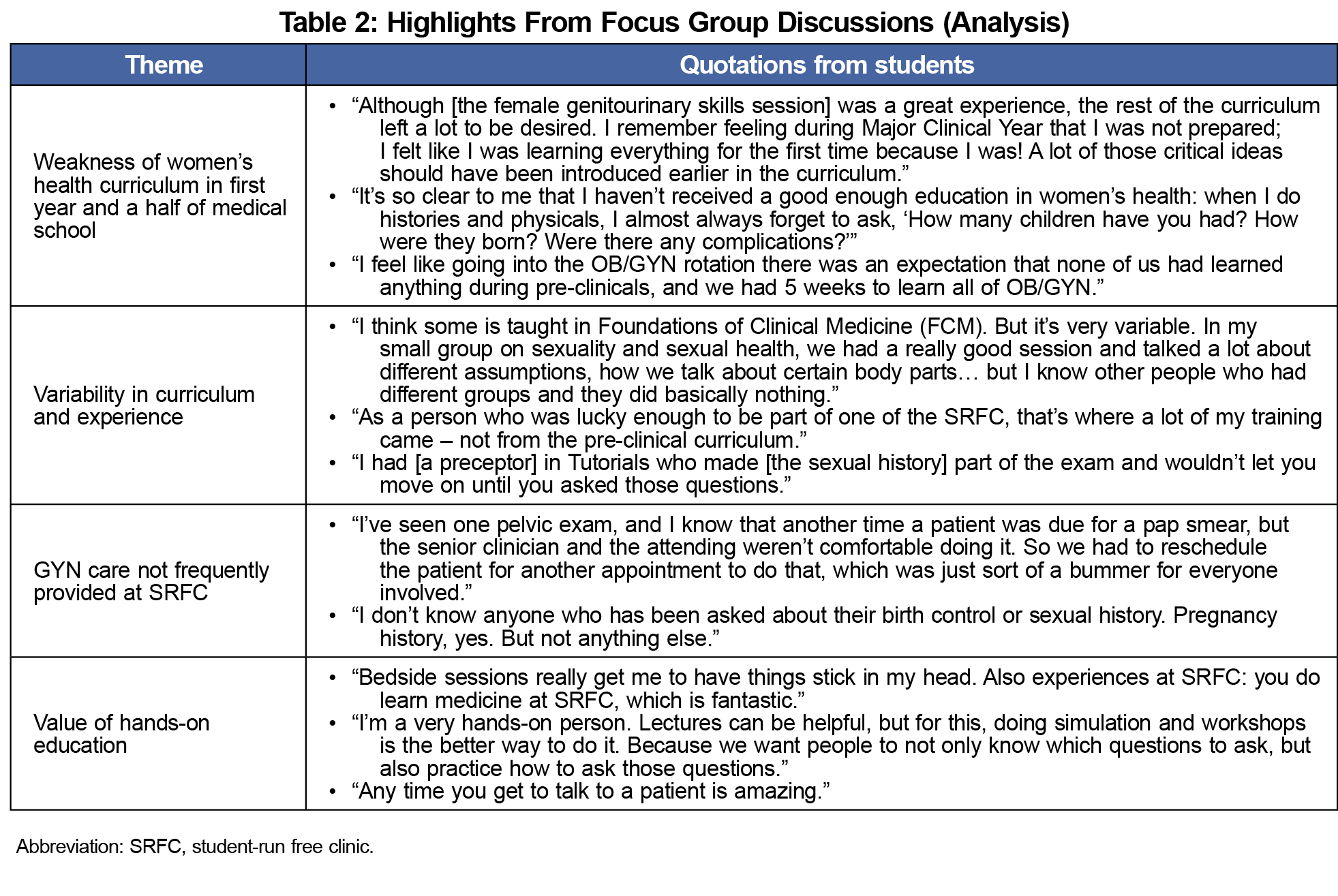

Four preclerkship and eight senior-level students shared their experiences with women’s health education during the focus groups. Common themes included variability in the curriculum, desire to build upon established skills in broaching sensitive topics, value of hands-on education, and importance of early exposure (Table 2).

Design and Development

Using feedback from needs assessment, a fourth-year medical student and attending physician conceived a 4-hour workshop. The student-led tutorial reviewed practical skills, how to have difficult conversations with patients, and reinforcement of the concepts of a well-woman history. We invited 151 second-year students to participate in the workshop. Six consented to complete the study including workshop and SRFC, and 21 consented to serve as controls. There were no demographic or baseline differences between groups. Age and sex were not statistically significantly different and there were no differences at baseline regarding prior experience with women’s health, confidence in relevant skills, and subjective readiness for clinical rotations (Table 3).

Evaluation

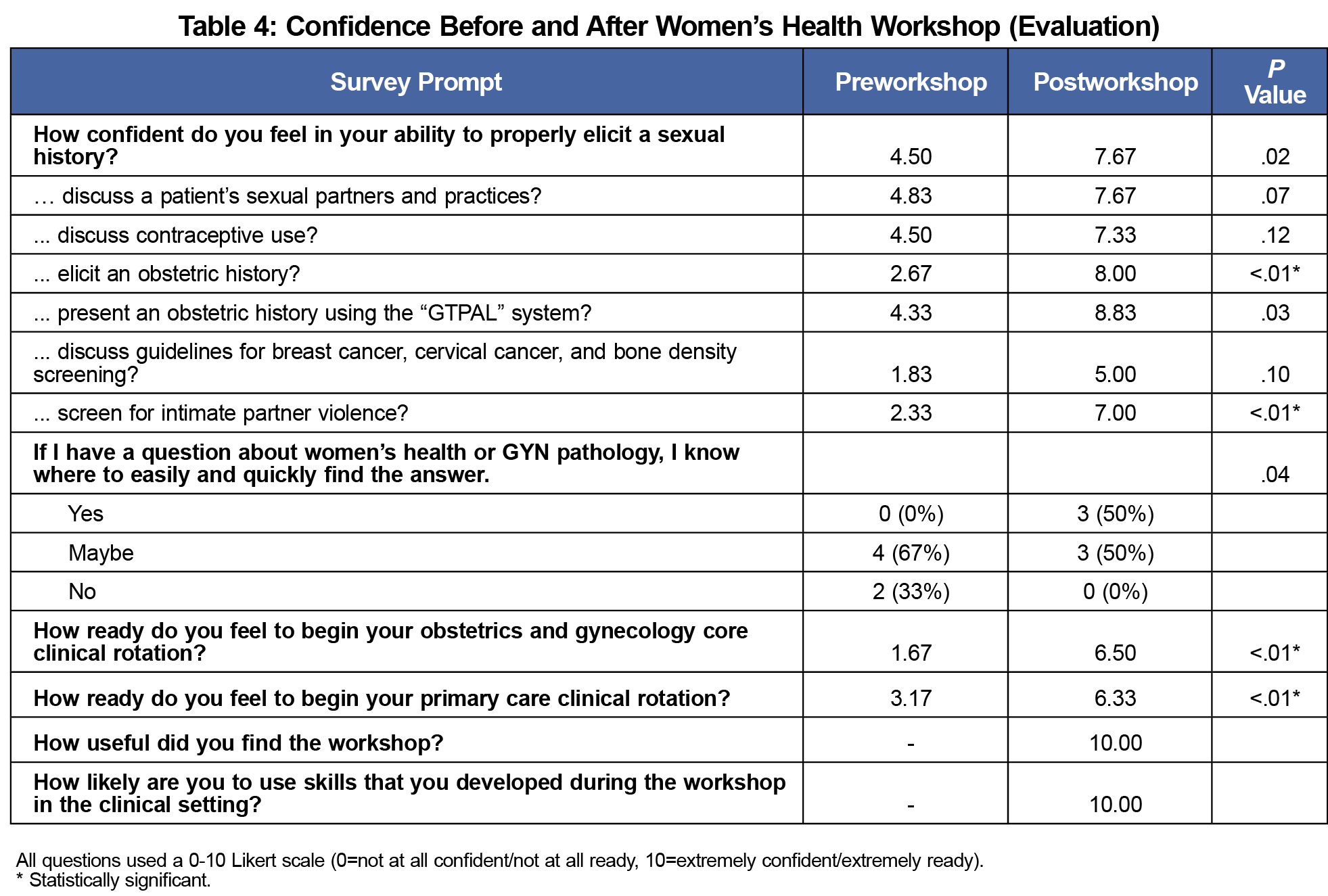

After the workshop, students reported improved confidence in several women’s health-related skills and in readiness for OB/GYN and primary care core clinical rotations with statistically significant increases above the control; gains persisted at 3 months (Tables 3 and 4). Six of six workshop participants and 12 of 21 control students completed 3-month follow-up surveys. Of the workshop group, 50% volunteered at SRFC during the semester.

This women’s health curricular model utilized an extensive needs assessment to devise a student-inspired, student-created, and student-led workshop for preclinical medical students. The developed educational intervention resulted in significant increases in subjective readiness for the OB/GYN rotation and confidence in women’s health-related skills. These gains persisted at 3 months. There was no difference in readiness for primary care rotations at 3 months, highlighting the many facets of primary care beyond women’s health. Students responded positively to study involvement, sharing that the workshop should be “required for everyone.”

The workshop was complemented by SRFC participation. SRFC provides exposure to health maintenance and cancer screening at rates comparable to the national average.8,9 However, our SRFC provides weaker exposure to a complete history-taking experience and to limited sexual health counseling.10 This weakness highlights lost educational opportunity. While the SRFC is an important component of the preclerkship experience for many students, this limited curricular review and small cohort are not powered to demonstrate its direct impact on the development of women’s health skills.

The most significant strength of this study is that the intervention is reproducible and adaptable. This educational pilot was devised and taught by a fourth-year medical student and could be facilitated by a senior medical student, resident, or faculty member. The intervention was built upon student feedback. A similar program could be implemented in other American medical schools.

The small number of participants is a major limitation. The intended general audience of medical students was likely not reached by this voluntary tool. The interventional impact may depend upon each medical school’s structure; student response may differ at a program with a previously established and robust women’s health curriculum.

Students are dissatisfied with the status quo women’s health curriculum, but the addition of a brief interactive educational intervention has lasting impact on subjective readiness and confidence. While active learning participation seems to drive these improvements, SRFC may be a useful adjunct to classroom learning. Further research into the applicability of SRFC and the impact of a mandatory women’s health curriculum is warranted.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This study was supported by the Scholarly Project Fund at the Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Presentations: This work was presented at the Northeastern Group on Educational Affairs (NEGEA) 2019 Annual Conference on April 4, 2019 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

References

- Steinauer J, LaRochelle F, Rowh M, Backus L, Sandahl Y, Foster A. First impressions: what are preclinical medical students in the US and Canada learning about sexual and reproductive health? Contraception. 2009;80(1):74-80. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2008.12.015

- Henrich JB, Viscoli CM, Abraham GD. Medical students' assessment of education and training in women's health and in sex and gender differences. Journal of women's health (2002). 2008;17(5):815-827.

- Windish DM, Paulman PM, Goroll AH, Bass EB. Do clerkship directors think medical students are prepared for the clerkship years? Acad Med. 2004;79(1):56-61. doi:10.1097/00001888-200401000-00013

- Johnson K, Rullo J, Faubion S. Student-initiated sexual health selective as a curricular tool. Sex Med. 2015;3(2):118-127. doi:10.1002/sm2.57

- Shinnick J, Spelke MB, Martinez AR. Student-led training day increases student confidence in women’s primary care skills. Fam Med. 2016;48(7):551-555.

- Nakamura M, Altshuler D, Chadwell M, Binienda J. Clinical skills development in student-run free clinic volunteers: a multi-trait, multi-measure study. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):250. doi:10.1186/s12909-014-0250-9

- Nitschmann C, Bartz D, Johnson NR. Gynecologic simulation training increases medical student confidence and interest in women’s health. Teach Learn Med. 2014;26(2):160-163. doi:10.1080/10401334.2014.883984

- National Cancer Institute. Online Summary of Trends in US Cancer Control Measures: Cervical Cancer Screening. 2017; https://progressreport.cancer.gov/detection/cervical_cancer. Updated March 2020. Accessed July 7, 2020.

- National Cancer Institute. Breast Cancer Screening: Online Summary of Trends in US Cancer Control Measures. https://progressreport.cancer.gov/detection/breast_cancer. Updated March 2020. Accessed July 7, 2020.

- United States Preventive Services Task Force. Final Update Summary: Sexually Transmitted Infections: Behavioral Counseling. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/sexually-transmitted-infections-behavioral-counseling1?ds=1&s=sexual. Published 2016. Accessed July 7, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines. https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/clinical.htm. Accessed July 6, 2020.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Well-Woman Recommendations. https://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Annual-Womens-Health-Care/Well-Woman-Recommendations. Accessed July 7, 2020.

- United States Preventive Services Task Force. Final Recommendation Statement: Intimate Partner Violence, Elder Abuse, and Abuse of Vulnerable Adults: Screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/intimate-partner-violence-and-abuse-of-elderly-and-vulnerable-adults-screening1. Published October 23, 2018. Accessed June 2019.

There are no comments for this article.