The influence of social determinants of health (SDOH) on health outcomes is well understood, contributing to approximately 80% of patient morbidity and mortality.1 Though concepts addressing the management of SDOH should be introduced during medical students’ preclinical education, no validated educational methodology exists to provide guidance on how to integrate SDOH within the competency-based training of medical students’ clinical years. To respond to the demands of the new learning environment post-COVID-19, a telehealth elective was created to encourage student participation in patient encounters. Asynchronous and synchronous educational materials helped frame patient encounters with evidence-based guidelines and safe spaces for individual and group reflection. COVID-19, and the ensuing social, economic, and emotional disruptions, provided an opportunity to bolster the knowledge base developed by students during preclinical years with a competency-based curriculum on SDOH and cultural humility. This service-driven programming allowed students to gain important skills in interpersonal communication, case management, and an understanding of the role of SDOH in our patients’ lives. Simultaneously, patients in the community were provided nonclinical psychosocial support during the spring 2020 wave of COVID-19. Guided by the pedagogy of Friere and Dewey, our curriculum allowed SDOH to be taught in a setting where altruism, empathy, and humility were reinforced.2,3

SPECIAL ARTICLE

Integrating Social Determinants of Health Into Clinical Training During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Orlando Solá, MD, MPH | Crystal Marquez, MD

PRiMER. 2020;4:28.

Published: 10/14/2020 | DOI: 10.22454/PRiMER.2020.449390

Introduction: Social determinants of health (SDOH) are often incorporated to some degree within preclinical medical education, but no validated curriculum exists for the incorporation of SDOH and the competencies necessary to address nonclinical contributors to health, within clinical educational programming. The COVID-19 pandemic provided an opportunity to implement this programming in a virtual setting.

Methods: Using pedagogy developed by Freire and Dewey, we created a service-learning curriculum supported by reflection sessions, workshops on implicit bias, and journal clubs. We used flipped classroom and adult-learning theory to develop and implement this curriculum.

Results: Learners showed significant enthusiasm for this novel curriculum, identifying the incorporation of SDOH and related competencies in clinical education as unique and imperative, requesting that the content be further integrated within the clinical experience of State University of New York Downstate Health Sciences University.

Conclusion: We developed a service-based curriculum that succeeded in developing further understanding of how patients experience their health in Central Brooklyn, and provided a space for students to generate emotional and interpersonal expertise that is important for the growth of clinicians in caring for patients in underserved and underresourced communities.

Our curriculum was composed of a student-driven community outreach component, where calls were made to University Hospital Brooklyn (UHB) patients to assess for nonclinical needs and provide psychosocial support. We derived outreach protocols from validated SDOH screening tools (Accountable Health Communities [AHC]; Health-Related Social Needs [HRSN], Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences [PRAPARE]; and AAFP Social Needs Screening Tool), and informed by anecdotal expertise on the Central Brooklyn community. Decision algorithms linked positive triggers with resource lists that helped students connect patients with community-based organizations and government resources. Due to Association of American Medical Colleges limitations during COVID-19, this elective was branded nonclinical and any clinical complaints were referred to an on-call list of faculty attendings.

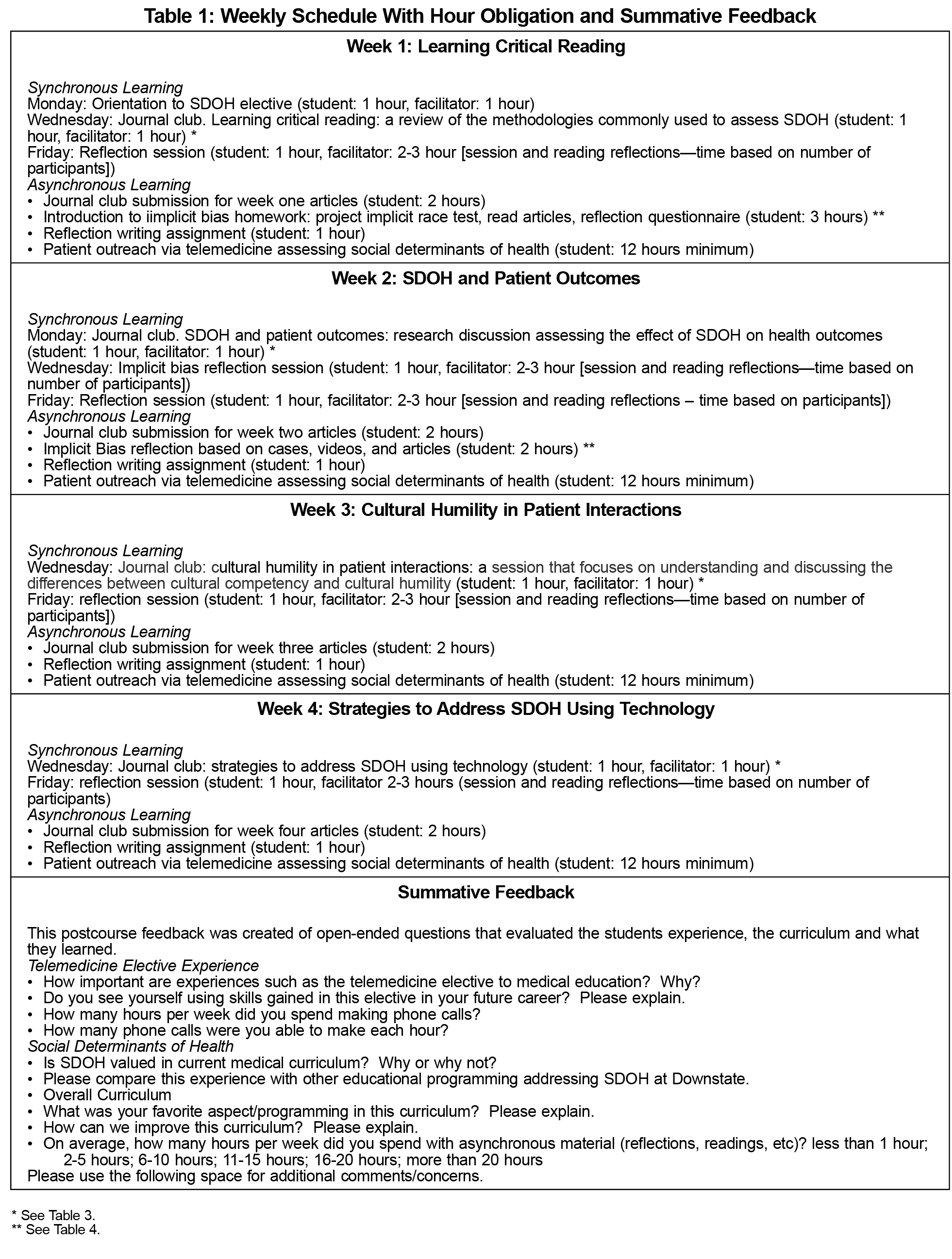

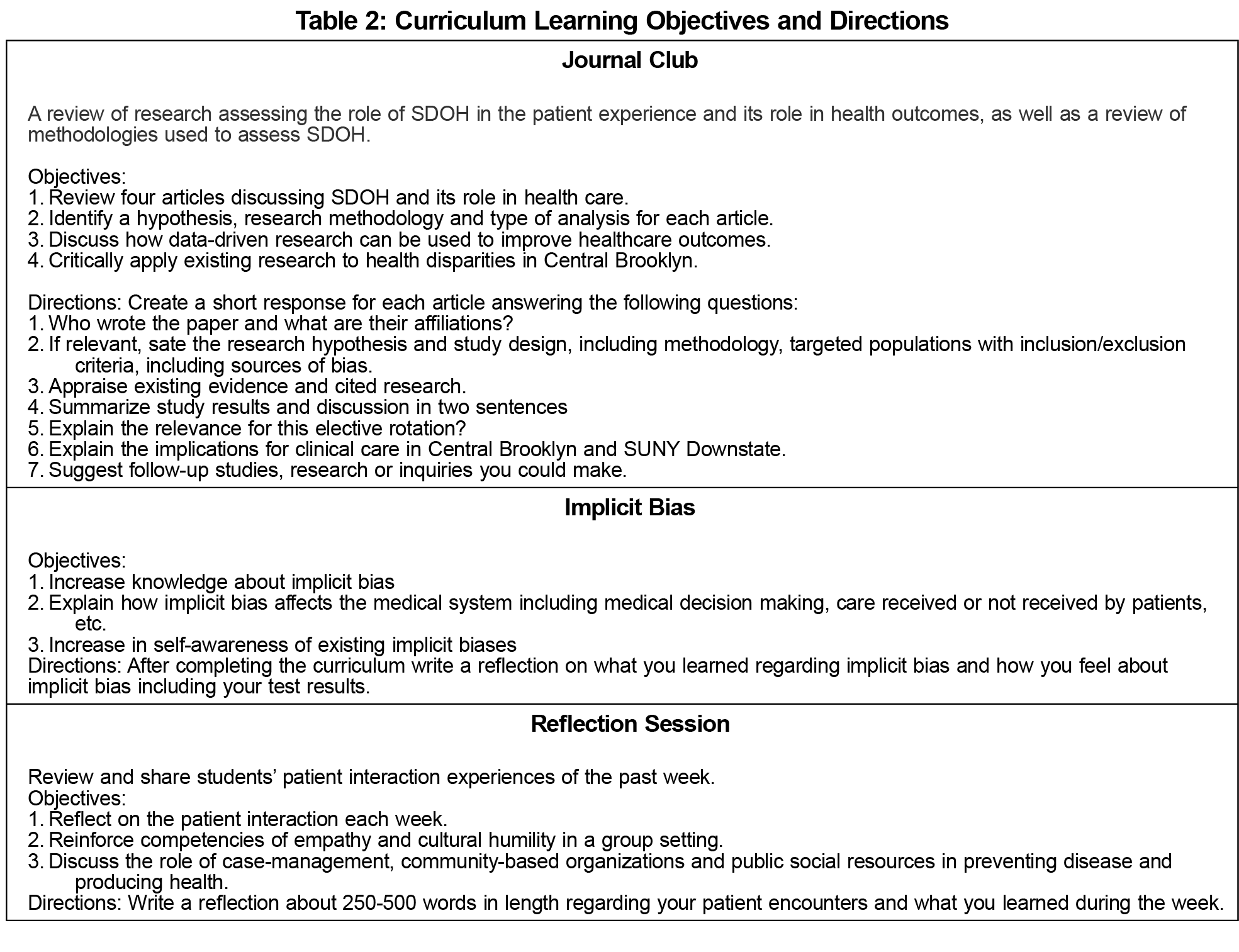

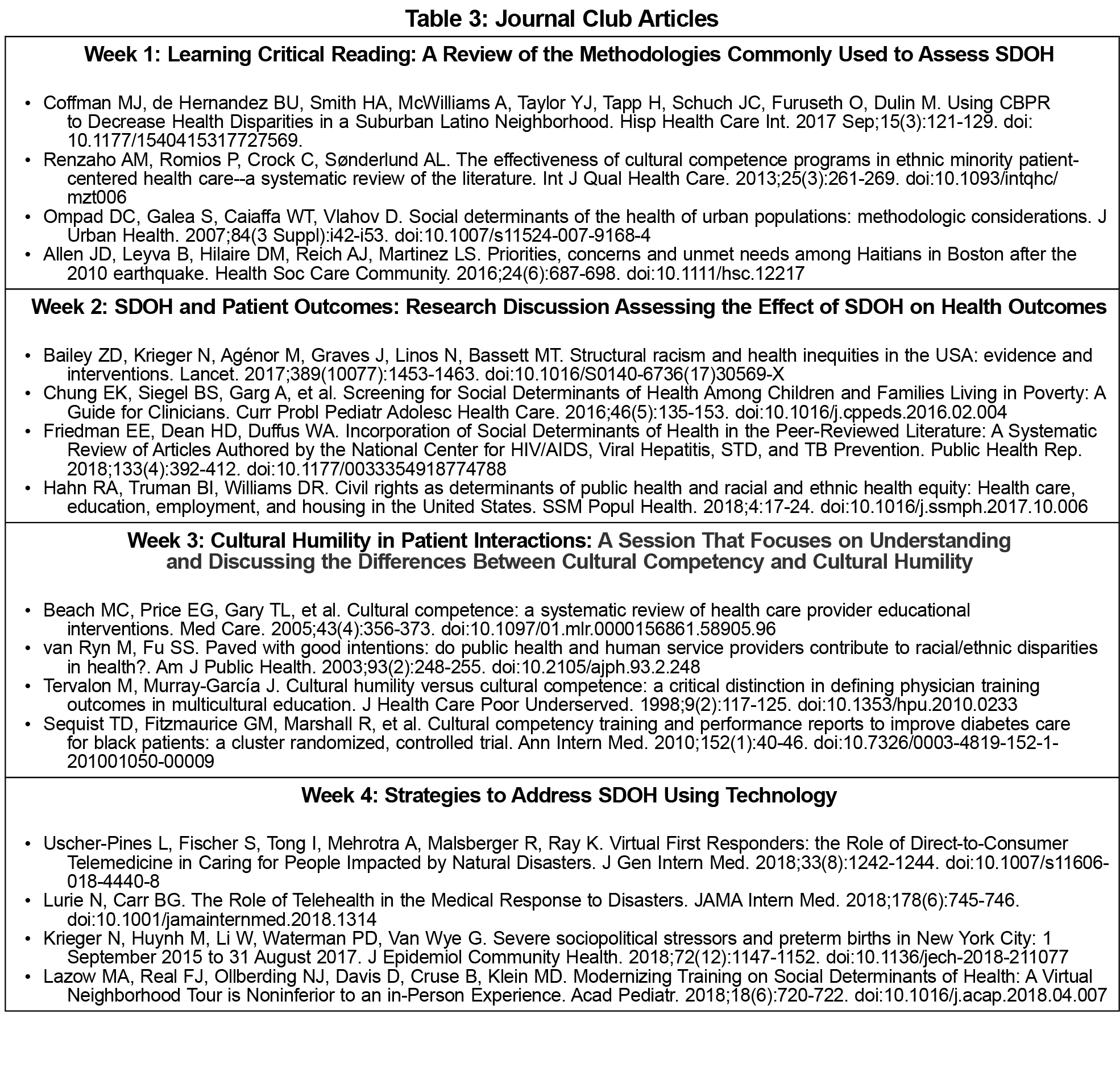

We organized the elective into weekly sections. Each week began with a journal club session, followed by implicit bias training and ending in individual and group reflection sessions. Using the flipped classroom and service-learning models, we first provided students readings that help establish foundational knowledge on relevant clinical trends as well as the skills necessary to provide competent care to underserved communities. These competencies were reinforced by patient interactions and interactive implicit bias trainings. To bring closure, each week ended with reflective sessions where an open, supportive learning environment allowed students to organically crystallize important lessons from the week and share them with the group. We based the learning objectives of the didactic components on faculty review of student reflections, allowing the student experience to play a central role in curriculum building.

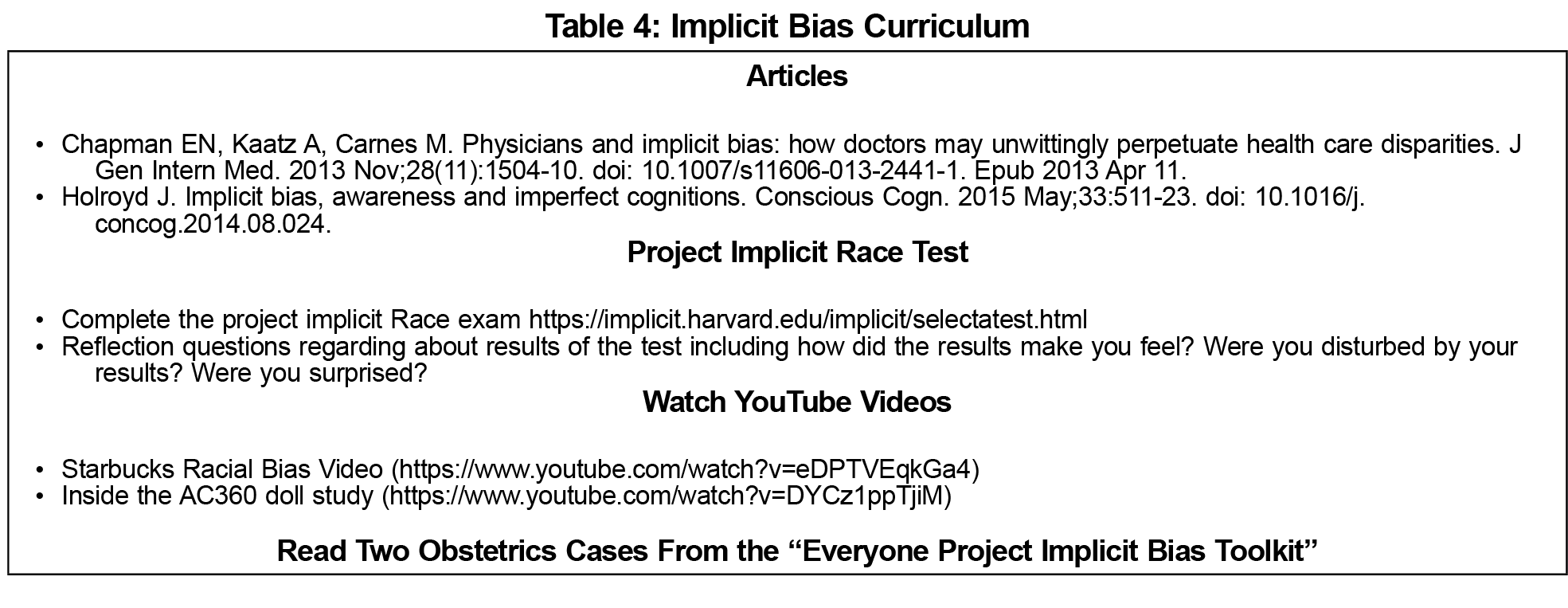

Implicit bias training and journal club sessions ensured students were appropriately equipped to interact with economically vulnerable and socially traumatized communities in Central Brooklyn. Journal club sessions allowed students to review, analyze, and critically discuss research addressing SDOH, cultural humility, and innovations in providing care to marginalized communities. Implicit bias training empowered students to understand the role of personal beliefs and culture in interpersonal reactions. Through these sessions students built upon an existing fund of knowledge gained in preclinical and clinical education to enhance clinical skills and the health care quality provided to UHB patients.

Group reflection sessions were the most important didactic component. At the end of each week students completed personal reflections that faculty used to drive a moderated group discussion. Teaching faculty reviewed written student reflections and discussed themes that would be used to guide the group discussion, where faculty moderators built on the anecdotal wisdom students gained through the services provided to UHB patients. Using the student experiences to drive the learning objectives and educational content ensured the educational needs of learners were being met and allowed the curriculum to adjust to the evolving needs of the local community.

The companion article "Medical Students Screen for SDOH: A Service-Learning Model to Improve Health Equity" provides an analysis of this project from the perspective of medical students.

Our institutional review board (IRB) gave this curriculum a “determination of not research” exemption (case 1596508-1), and the IRB deemed exempt the component of the curriculum that resulted in patient outreach (case 1600930-1).

Since initiating this service activity in March there have been 35 student participants, reaching approximately 1,000 adult patients and identifying needs for community-based resources after 393 screens. Additionally, there were 32 social work referrals generated, 217 medication refill requests, 102 intradepartment appointment requests, and 31 appointment requests with other departments.

Student reflections identified several shared themes including how students experienced interacting with patients over the phone, in which they created longitudinal relationships with consistent follow-up and assistance with community-based resources. Furthermore, students were able empathize and sympathize with patients during the shared experience of the COVID-19 pandemic. Student participants were often surprised at the level of chronic crisis many of the families in Central Brooklyn suffer from, and how current pandemic-related problems seem trivial when taken in context of preexisting daily struggles.

Summative feedback collected from students demonstrated a singular and explicit incorporation of SDOH in a clinical experience that is not repeated elsewhere. Communicating with patients while at home, and addressing nonclinical contributors to health, developed a unique knowledge base and communication skill set that helped engender a spirit of sympathy and humility between students and patients. Student respondents also encouraged further incorporation of the rotation within regular clinical care.

As medical education continues to evolve, new technology provides an opportunity for educators to develop novel curriculum and expand the venues through which students can interact with patients. The initial COVID-19 crisis and associated quarantine provided a unique opportunity to trial innovative curriculum and address unmet nonclinical needs within our patient community. By participating in this service-learning curriculum, students were able to develop rich connections with patients where they grew as providers, gained humility in their approach to patients, and developed a new understanding of the limits to clinical care. Lastly, as an additional benefit, replication of this curriculum can allow hospitals to leverage their student workforce to expand support for patient communities and help address nonclinical SDOH that are often beyond the reach of clinicians.

References

- National Conference of State Legislatures. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. What State Legislators Need to Know. Washington, DC: National Conference of State Legislators; 2013. https://www.ncsl.org/portals/1/documents/health/HealthDisparities1213.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2020.

- Siegel, Jennifer MD; Coleman, David L. MD; James, Thea MD. Integrating social determinants of health into graduate medical education: a call for action. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):159-162. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002054

- Hunt JB, Bonham C, Jones L. Understanding the goals of service learning and community-based medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2011;86(2):246-251.

- Doobay-Persaud A, Adler MD, Bartell TR, et al. Teaching the social determinants of health in undergraduate medical education: a scoping review. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(5):720-730. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-04876-0

- Sharma M, Pinto A, Kumagai AK. Teaching the social determinants of health: a path to equity or a road to nowhere? Acad Med. 2018;93(1): 25-30 doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001689

Lead Author

Orlando Solá, MD, MPH

Affiliations: SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY

Co-Authors

Crystal Marquez, MD - SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University, Brooklyn, NY

Corresponding Author

Crystal Marquez, MD

Correspondence: SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University, 450 Clarkson Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11203. 718-270-2025.

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.