Introduction: There is a shortage of mental health services in rural America, and little research is focused on rural underserved communities. Our aim was to identify and map clinical mental health services located in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan (UP) and explore primary care physician (PCP) mental health service provision and barriers to access experienced by this population.

Methods: We mapped clinically active psychiatrists and inpatient psychiatric units in the UP, and identified high-risk regions based on >30 mile distance to ambulatory services or low inpatient bed to population ratio. We surveyed PCPs in identified high-risk areas regarding provision of mental health services, comfort with providing services, and perceived barriers to care.

Results: Half of UP counties had no psychiatrists, and only two counties had inpatient psychiatric beds. PCPs are attempting to fill gaps in care, and report comfort with treating depression and anxiety, but less comfort with treating with bipolar disorder and substance use. Nearly all PCPs report barriers to accessing mental health resources; 70% report no psychiatrists to whom they can readily refer.

Conclusion: Michigan’s UP has a shortage of mental health resources. Proposed strategies to confront this shortage include additional training of PCPs for substance use and bipolar disorder, bolstering the mental health workforce, and improving access to consultative services.

The United States has a shortage of mental health professionals; rurality and poverty are strong predictors of unmet need.1 Primary care physicians (PCPs) often fill gaps in mental health care. PCPs manage psychiatric disorders for one-third of their patients and treat two-thirds of all patients with depression,2 a ratio that may be higher in rural areas, many of which are designated Mental Health Professional Shortage Areas.3 Telepsychiatry has also been demonstrated as an effective care delivery option in underserved areas.4,5

Michigan’s Upper Peninsula (UP) consists of 15 remote counties, all mental health professional shortage areas.6 Inhabitants have significant mental health needs, including increased rates of suicide.7,8 This combination of remoteness, lack of access, and a high-need population made the UP an ideal region for our objectives: identify rural mental health resources, study how rural PCPs adapt practices to meet mental health needs, and identify care-delivery barriers in order to design more effective outreach programs.

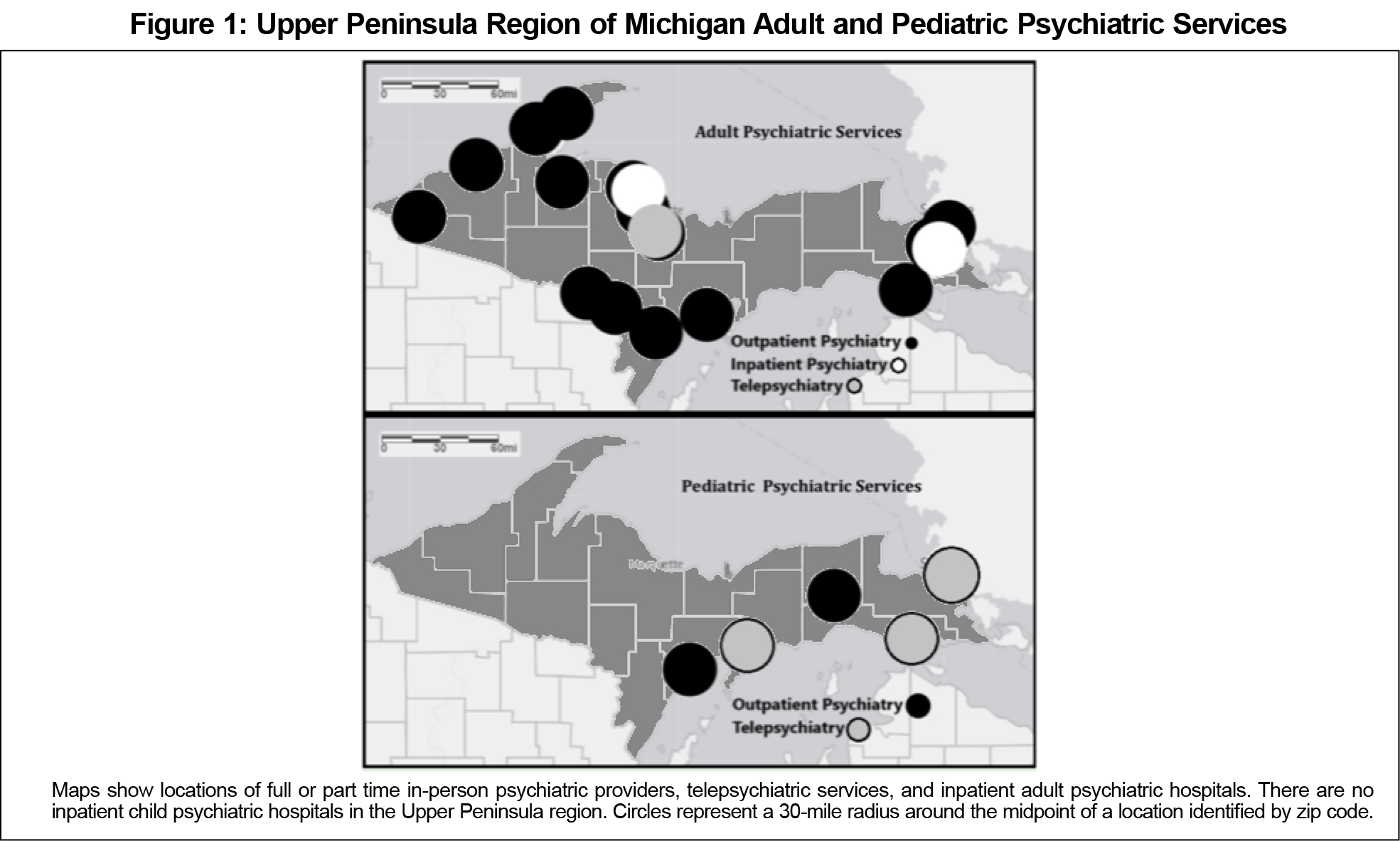

We completed a cross-sectional, two-phase descriptive study in 2018. We mapped full- and part-time adult and child psychiatric providers (psychiatrists and psychiatry-associated advanced practice providers) and inpatient psychiatric units in Michigan’s UP using publicly available data from the Upper Peninsula Health Plan, an organization for UP residents enrolled in Medicaid.6 We phoned each county’s Community Mental Health (CMH) agency to confirm providers and inpatient units, and to inquire about telepsychiatry use. We clarified discrepancies by contacting providers’ offices. We contacted inpatient facilities to determine the number of beds available.

We used Google Maps to map and overlay data on the US Census Bureau’s9 template with a 30-mile radius marker for each inpatient and outpatient location.

We defined high risk areas as those over 30 miles from a psychiatric access location, using Michigan Medicaid primary care recommendations10; high-risk regions from an inpatient standpoint were those with bed-to-population ratios of <50:100,000, consistent with recognized targets.11

Phase 2 explored PC-provided mental health services and barriers to access in the identified high-risk regions. We defined PCPs as family medicine, internal medicine, pediatric, and medicine/pediatric physicians and associated advanced practice providers. We contacted office managers of each PC practice in high-risk areas by phone, asking if they would share the survey link once with providers.

The survey consisted of 11 questions regarding demographics, prevalence of mental health concerns, accessibility of psychiatric providers, barriers to care, and mental health services provided versus those services respondents were comfortable providing. All survey questions are available in the STFM Resource Library.12

We compared categorical data using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate, with significance set at P<.05. The Michigan State University (MSU) Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Mapping

Figure 1 depicts adult and pediatric psychiatric services. All 15 counties were high risk according to both inpatient and outpatient study definitions. The region’s two most populated counties housed almost half of the UP’s 25 psychiatric providers and the only adult inpatient psychiatric units, with 39 beds in total (13 beds:100,000 ratio). There were only two part-time child psychiatrists and no child psychiatry beds. Several sites were staffed by psychiatrists who worked at multiple centers.

We surveyed 257 PCPs, with a response rate of 30.0% (77/257); respondents represented 14 of 15 UP counties. Of respondents, 89.6% (69/77) indicated PCPs are an influential source of providing psychiatric care. Almost one-third of respondents (31.2%, 24/77) stated >50% of their patients presented with psychiatric concerns. Most providers (89.6%, 69/77) indicated there were no readily available psychiatrists within their counties, and 70.1% (54/77) stated there was no one to whom they could easily refer their patients.

Most UP PCPs prescribed medication for depression and anxiety, both initiation (83.1%, 64/77) and continuation (85.7%, 66/77). Almost all prescribers were comfortable providing this service, and almost all nonprescribers were not comfortable (96.9%, 62/64 prescribers comfortable with initiation and 97.0%, 64/66 prescribers comfortable with continuation; 15.4%, 2/13 nonprescribers comfortable with either continuation or initiation, P<.05). About half (50.6%, 39/77) cared for patients with a substance use disorder, but the proportion comfortable with this service (28.6%, 22/77) was significantly less than those providing care (P<.05). PCPs indicated a similar discordance between medication initiation in bipolar disorder (46.8%, 36/77) and comfort with this service (28.6%, 22/77; P<.01). Counseling services were provided by 32% (25/77) of PCPs, but only 21% (16/77) were comfortable doing so; this was not a statistically significant difference (P=.14), but is important as a descriptive finding.

Virtually all respondents (98.7%, 76/77) stated that their patients encountered barriers, including long wait lists (87%, 67/77), lack of insurance (49.4%, 38/77), and counselors’ lack of availability (46.8%, 36/77). A significant proportion of PCPs (43%, 33/77) indicated patients had been told they were not sick enough for mental health services. Only 18.2% (14/77) of PCPs noted patients had refused mental health services when referred. Transportation was noted as a patient barrier by 35.1% (27/77) of providers, which is important given the vast area and aging population. Free-text responses echoed these concerns; shortages of psychiatrists throughout the region made for long wait lists, up to 12 months.

Michigan’s rural UP has a concerning shortage of mental health services, most acute in the pediatric population, despite great need. This finding is consistent with the literature on rural mental health care shortages.13,14 PCPs are attempting to meet mental health needs, at times by providing care they are not entirely comfortable providing. Many providers struggle to obtain specialty support.

Based on these findings, we propose several recommendations. First, we recommend additional training and support for PCPs focused on the complex mental health care issues being treated, specifically substance use and bipolar disorder; and additional training in primary counseling techniques. Additionally, consultative psychiatry care could be focused on diagnoses that PCPs are less comfortable treating.

Second, we recommend developing strategies to increase the number of rural-trained psychiatrists. UP Health System and MSU recently developed a psychiatry rural training track, building on MSU College of Human Medicine’s rural medical school programs.15 This is potentially a replicable strategy to bolster the rural psychiatry workforce.

Telemedicine is a third strategy to support the mental health work force, including traditional referral, collaborative care, consultation, consultation-liaison, and curbside consultation models.16 We recommend using a combination of models and placing virtual access points in the highest-need communities. The University of Michigan MC3 program is one such psychiatry consultation service, supporting rural PCPs managing children with mental health needs.17,18 Providing funding for similar programs would be a relatively cost-efficient way to address this critical rural need.19 Telemedicine use has only increased in the era of COVID, expanding the possibilities to meet rural need.

Our study has several limitations. We studied a single, rural region, limiting generalizability. We relied on PCPs to report patient barriers. We used Medicaid data and CMH to identify services, possibly missing psychiatrists who excluded Medicaid patients. Lastly, we did not address the distribution of PCPs, which may also impact access to care.

There is a shortage of mental health resources within Michigan’s rural UP. PCPs are attempting to meet this population’s mental health needs, yet are they struggle with a lack of available psychiatric resources. Supporting the region’s PCP workforce should target additional PCP training in substance use and bipolar disorders, bolster the region’s mental health workforce, and improve access to consultative services, including telemedicine.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Temmy Brotherson, MD, for her contributions to the early development of this project

Presentations: This study was presented at the following venues:

- Michigan Center for Rural Health’s 1st Annual Student and Resident Rural Health Research Day, May 3, 2018 [Poster Presentation]. Mount Pleasant, MI.

- National Rural Health Association’s 41st Annual Conference, May 10, 2018 [Poster Presentation]. New Orleans, LA.

- 41st Annual Michigan Family Medicine Research Day Conference, May 24, 2018 [Oral Presentation]. Howell, MI.

- Western Michigan University’s Health Equity Summit, June 30, 2018 [Oral Presentation]. Kalamazoo, MI.

- 2019 World Rural Health Conference, October 2-15, 2019 [Poster Presentation]. Albuquerque, NM.

References

- Thomas KC, Ellis AR, Konrad TR, Holzer CE, Morrissey JP. County-level estimates of mental health professional shortage in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(10):1323-1328. doi:10.1176/ps.2009.60.10.1323

- Mental Health Care Services by Family Physicians. 2018. American Academy of Family Physicians. Accessed March 8, 2019. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/mental-services.html

- Shortage Designation: Health Professional Shortage Areas. Health Resources and Services Administration. Updated September 27, 2019. Accessed September 28, 2019. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/shortage-areas.

- Conn D, Gajaria A, Madan R. Telepsychiatry: effectiveness and feasibility. Smart Homecare Technol Telehealth. 2015;59(April):59. doi:10.2147/SHTT.S45702

- Hilty DM, Ferrer DC, Parish MB, Johnston B, Callahan EJ, Yellowlees PM. The effectiveness of telemental health: a 2013 review. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19(6):444-454. doi:10.1089/tmj.2013.0075

- Upper Peninsula Health Plan. Accessed April 21, 2020. https://www.uphp.com

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 17-5044, NSDUH Series H-52). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Accessed March 8, 2019. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR1-2016/NSDUH-FFR1-2016.htm

- CDC National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed September 20, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/mental-health.html

- United States Census Bureau. Report generated by Jenna Bernson using American FactFinder. Accessed September 26, 2019. https://factfinder.census.gov

- Murrin S. State Standards for Access to Care in Medicaid Managed Care. United States Department of Health and Human Services; Office of Inspector General. September 2014. Accessed March 8, 2019. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-11-00320.pdf

- Treatment Advocacy Center. Psychiatric Bed Supply Need Per Capita: Background Paper. September 2016. Accessed May 14, 2019. https://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/storage/documents/backgrounders/bed-supply-need-per-capita.pdf

- Bernson J. Wendling A. Examining Access to Psychiatric Care in Michigan's Remote Upper Peninsula - Appendix of Survey Questions. STFM Resource Library. Uploaded September 30, 2021. Accessed November 12, 2021. https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/examining-access-to-psychiatric-car?CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a&tab=librarydocuments

- Gamm L, Stone S, Pittman S. Mental Health and Mental Disorders - A Rural Challenge: A Literature Review. Rural Healthy People 2010: A Companion Document to Healthy People 2010. 2010; 2:97-113. Accessed March 8, 2019. https://srhrc.tamhsc.edu/docs/rhp-2010-volume2.pdf.

- Hartley D, Ziller EC, Loux SL, Gale JA, Lambert D, Yousefian AE. Use of Critical Access Hospital Emergency Rooms by Patients With Mental Health Symptoms. Wiley Online Library. Published March 28, 2007. Accessed May 1, 2021. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2007.00077.x. doi:10.1111/j.1748-0361.2007.00077.x

- Wendling AL, Phillips J, Short W, Fahey C, Mavis B. Thirty years training rural physicians: outcomes from the Michigan State University College of Human Medicine Rural Physician Program. Acad Med. 2016;91(1):113-119. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000885

- Fortney JC, Pyne JM, Turner EE, Farris KM, Normoyle TM, Avery MD, Hilty DM, Unützer J. Telepsychiatry integration of mental health services into rural primary care settings. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2015;27(6):525-39. doi:10.3109/09540261.2015.1085838

- About MC3. University of Michigan, Department of Psychiatry. 2018. Accessed November 5, 2018. https://mc3.depressioncenter.org/about/

- Malas N, Klein E, Tengelitsch E, Kramer A, Marcus S, Quigley J. Exploring the telepsychiatry experience: primary care provider perception of the Michigan Child Collaborative Care (MC3) Program. Psychosomatics. 2019;60(2):179-189. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2018.06.005

- Shore JH, Brooks E, Savin DM, Manson SM, Libby AM. An economic evaluation of telehealth data collection with rural populations. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(6):830-835. doi:10.1176/ps.2007.58.6.830