Background and Objectives: Transitioning from medical school to residency is challenging, especially in rural training programs where a comprehensive scope of practice is needed to address rural health disparities. Oregon Health & Science University partnered with Cascades East Family Medicine Residency in Klamath Falls, Oregon to create an integrated fourth-year medical student experience (Oregon Family medicine Integrated Rural Student Training (Oregon FIRST). Participants may then enter this residency to complete their training with the intention to practice in rural underresourced settings.

Methods: In this exploratory study, we conducted key informant interviews with 9 of ten Oregon FIRST participants to determine how Oregon FIRST contributed both to their readiness for residency training and their choice to practice in rural underserved locations. Interviews were conducted between June 10, 2020 and July 8, 2020. We analyzed field notes taken during interviews for emergent themes using classical content analysis.

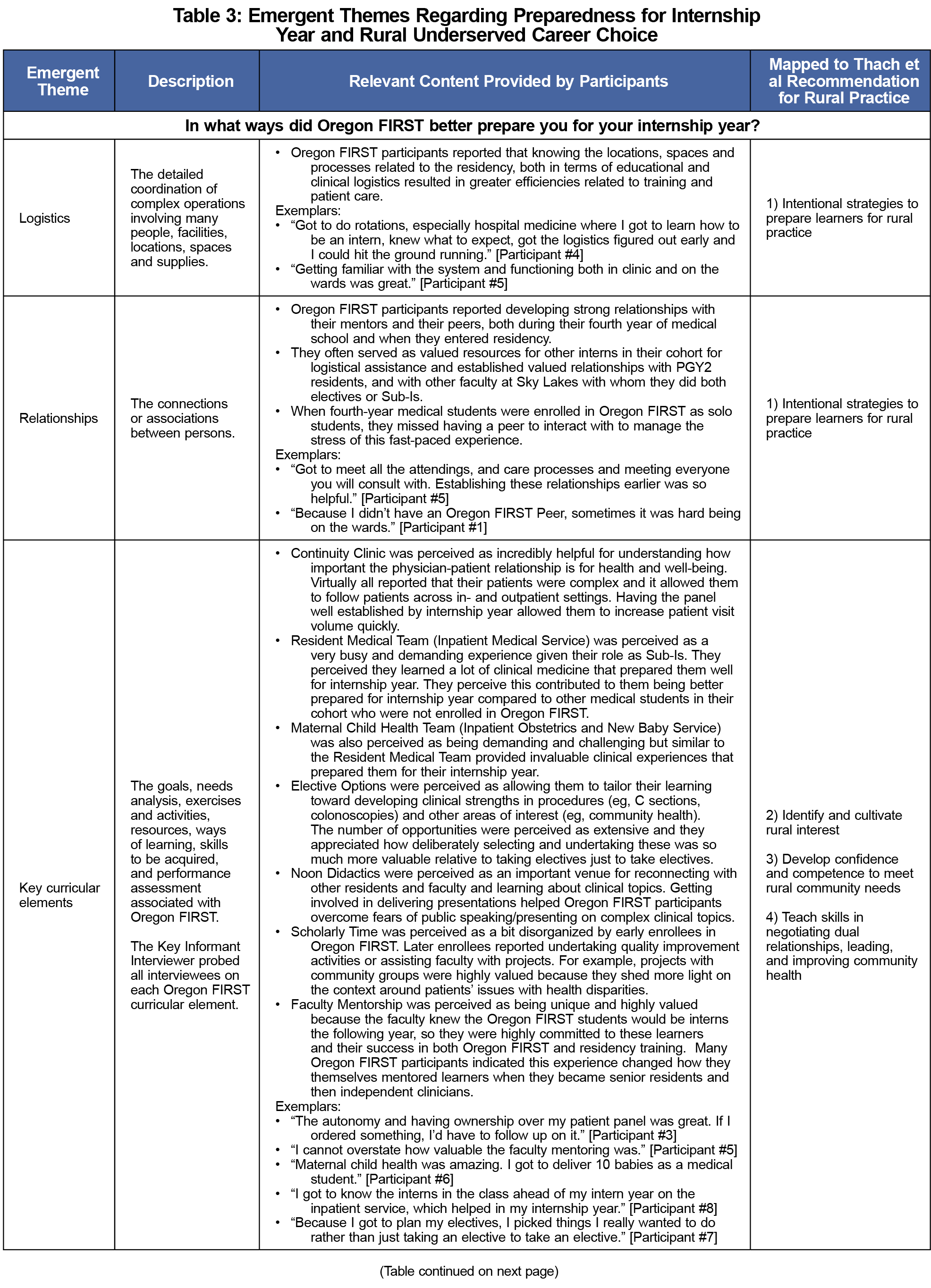

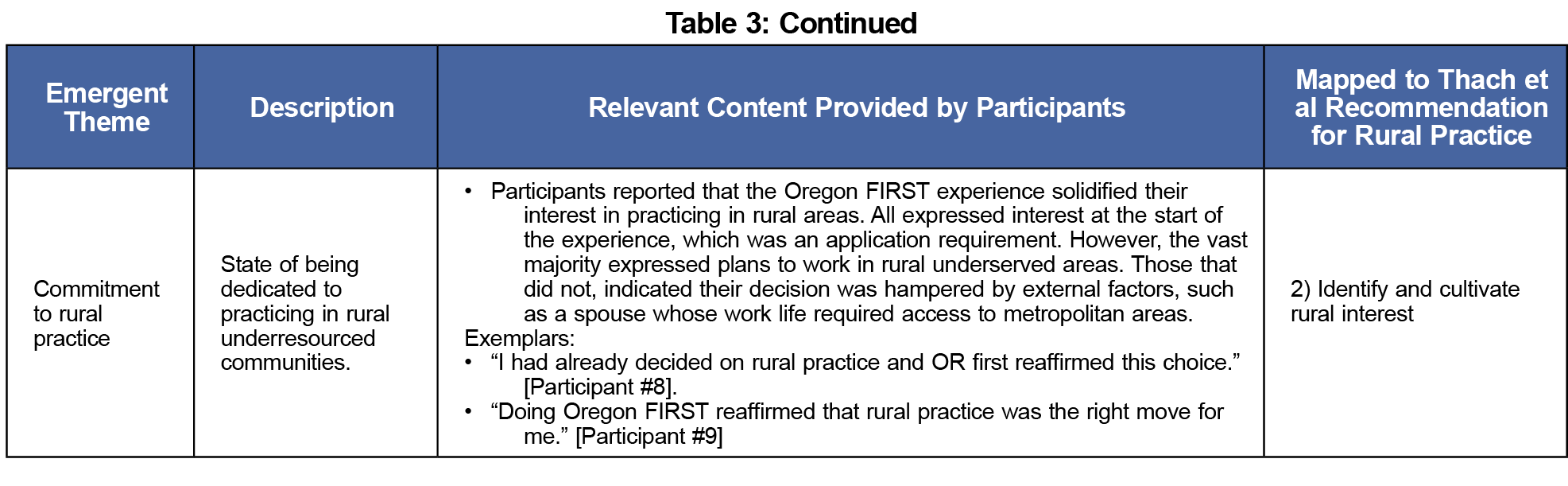

Results: Emergent themes included logistical ease, relationship development, key curricular elements, and commitment to rural practice. Overwhelmingly, Oregon FIRST participants reported the experience had many challenging and demanding components because they served as subinterns for their entire fourth year of medical school, but this prepared them very well for internship. When asked if they would choose to enroll in Oregon FIRST again, given what they now know about physician training and patient care, all nine (100%) said they would.

Conclusions: This study demonstrated that Oregon FIRST students felt better prepared for the rigors of residency and are committed to practicing in rural areas.

Transitioning from medical school to residency is challenging. Medical errors due to lack of preparedness have been reported.1,2 Residency programs have used boot camps, preparatory courses, and immersion rotations3-6 to ease the transition. Medical schools responsible for preparing learners for residency7 are adopting competency-based assessments to improve transitions to residency.8 Creating stronger partnerships between medical schools and residency programs is another strategy to improve preparedness.9, 10

Rural health disparities are worsening, and a broader scope of practice is needed.11, 12 Thach and colleagues13 identified five recommendations for rural practice preparation: (1) be intentional about strategies to prepare learners for rural practice; (2) identify and cultivate rural interest; (3) develop confidence and competence to meet rural community needs; (4) teach skills in negotiating dual relationships, leading, and improving community health; and (5) fully engage rural host communities throughout training.

To address these issues, Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) and Cascades East Family Medicine Residency (CEFMR) implemented Oregon Family medicine Integrated Rural Student Training (Oregon FIRST). Here we describe the study we conducted to assess participants’ experiences and early outcomes of Oregon FIRST using recommendations made by Thach et al.13

Setting, Development, and Implementation

CEFMR, administered by OHSU, is an 8-8-8 rural residency program based at Sky Lakes Medical Center in Klamath Falls, Oregon, a rural community of 21,934 people, 80 miles from the nearest tertiary care hospital.14 Oregon FIRST involves fourth-year OHSU medical students undertaking a 9-month family medicine subinternship in Klamath Falls (Table 1). After approval by Sky Lakes Medical Center leadership, Oregon FIRST was accepted by OHSU’s School of Medicine and enrollment began in 2014.

Medical Student Recruitment/Participation

OHSU medical students apply to Oregon FIRST during their third year and are selected with the same thoroughness as residency applicants. Applications include a personal statement of interest and goals, curriculum vitae, medical school transcript, grade narrative/Medical Student Performance Evaluation (MSPE) comments, United States Medical Licensing Exam I score, and two faculty letters of recommendation, one from a family physician. Each candidate receives a formal interview similar to residency interviews. Applicants are evaluated based on commitment to full-spectrum rural family medicine, academic achievements, and service activities.

In their fourth year, Oregon FIRST participants apply to CEFMR through Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) on the normal timeline, and participate in the National Residency Matching Program (NRMP). Two of CEFMRs eight intern positions are ideally filled with Oregon FIRST participants, though during some years only one student was selected. Though the NRMP offers an exception to its All In Policy15 for rural programs, it has not encouraged programs to apply when they can meet their program’s stated goals without an exception.16 Oregon FIRST emphasizes student safety in their ability to opt out and apply to other programs, while also offering students comfort that the selection process for Oregon FIRST matches the criteria for residency selection to foster confidence they are likely to match.

Experience Evaluation and Data Analyses

Oregon FIRST is in its sixth year. We conducted key informant interviews with nine of ten participants who completed the experience. Two students participated in each of 2014, 2016, 2017, and 2019, and one student participated in 2015 and 2018. Interviews were conducted between June 10, 2020 and July 8, 2020, and lasted 18-45 minutes (mean=34.3). We collected field notes with a review/validation step at the end of each interview and compiled into a single document for analyses. We used classical content analysis17 to identify emergent themes that addressed two research questions: (1) In what ways did Oregon FIRST prepare students for their internship year?, and (2) How did Oregon FIRST affect students’ choice to practice in rural underresourced settings? We additionally mapped our findings to Thach’s recommendations for rural practice preparation.13 Additional data were collected from administrative databases, including age, gender, and career status. All study activities were approved by OHSU’s Institutional Review Board (IRB # 21532).

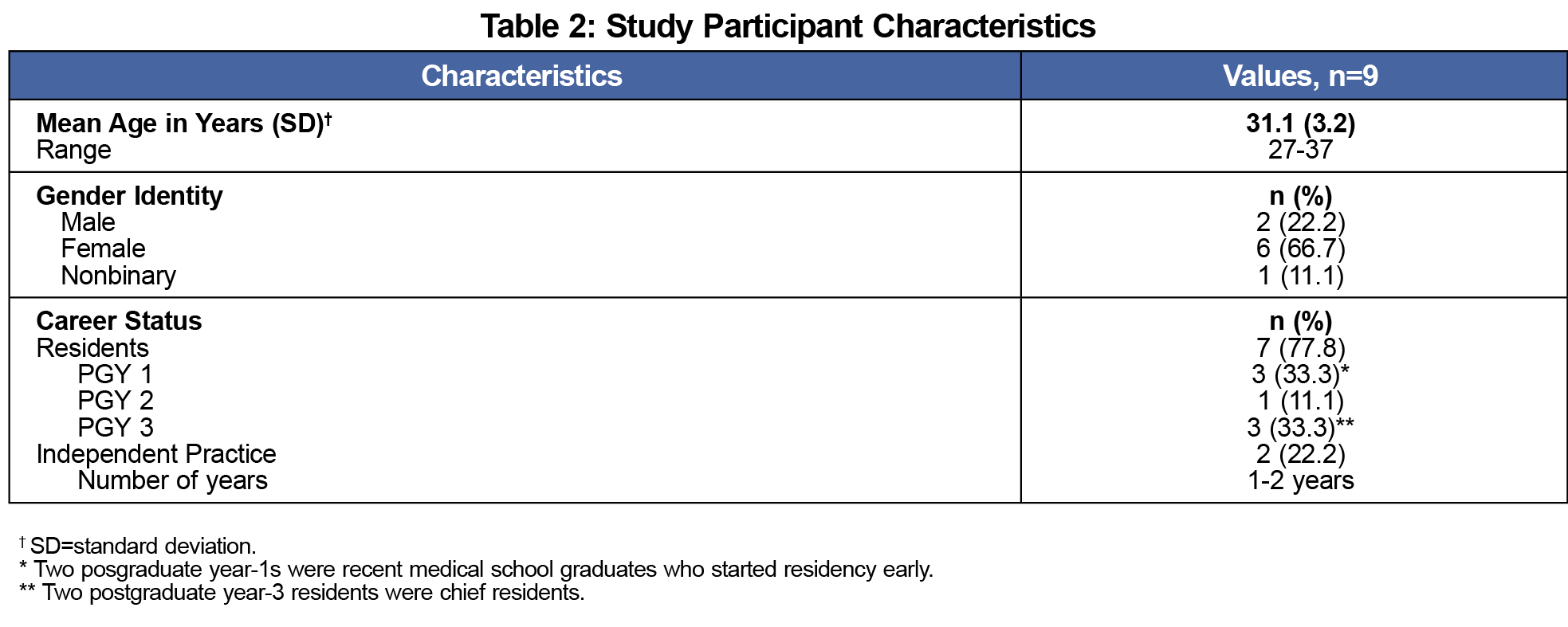

Participants’ average age was 31.1 years (SD=3.2); they were predominantly female (Table 2). Seven were residents, and two were in independent clinical practice. Emergent themes included logistics, relationships, key curricular elements, and commitment to rural practice (Table 3). Overwhelmingly, Oregon FIRST participants perceived receiving a better educational experience to prepare for residency compared to other fourth-year medical students in their cohort. They reported that by serving as subinterns for 9 months, they become more proficient at handling demanding experiences, such as many hours providing care to acutely ill patients, which helped prepare them for internship. When asked if they would choose to participate in Oregon FIRST again, 100% said they would.

Other outcomes from Oregon FIRST include that 100% matched at CEFMR, 100% of graduates achieved board certification in family medicine on their first attempt, one is a chief resident, and two are in independent clinical practice. Both graduates in independent clinical practice are doing full spectrum in- and outpatient and maternity care in rural Oregon. Two Oregon FIRST students for 2019/2020 completed their degree requirements and graduated early. After successfully matching at CEFMR in March, they started residency in April to assist with COVID-19 pandemic care.

This study demonstrated that Oregon FIRST students felt well prepared for the rigors of rural residency training and remained committed to rural practice. Becoming familiar with locations, spaces, and processes of residency created efficiencies and confidence performing the duties of an intern. Relationship development with peers and mentors was valued, as were key curricular elements, such as developing longitudinal relationships with patients seen in continuity clinic, which made it easier to see more patients during internship year. Inpatient rotations exposed them to complex patients, and elective time filled important gaps in knowledge/skills. The vast majority of participants expressed interest in rural practice before undertaking Oregon FIRST and it solidified that this was their best career choice. The two participants who undertook Oregon FIRST solo expressed difficulty associated with not having a medical student peer.

Oregon FIRST findings mapped to the first four of the five recommendations reported by Thach et al.13 The only one that did not map was fully engaging rural host communities throughout the training process. Though Oregon FIRST students did interact with host communities to meet Tach’s fourth recommendation, we have not figured out how to fully engage continuously during training due to strenuous schedules, but this is a future goal. One study that integrated internal medicine residency into the fourth year of medical school found that it increased the number of trainees entering primary care a year earlier while maintaining academic standards.10

Limitations of this study include small sample size, single-site study, and limited outcome data because it is too soon to have many graduates in clinical practice. Another potential limitation is social response bias of participants, though to mitigate this, the person conducting interviews (Author P.A.C.) was not known to participants. Future work will address these limitations, as the concept is now part of the California Oregon Medical Partnership to Address Disparities in Rural Education and Health, a partnership between OHSU and the University of California, Davis, where we will be working with 10 residencies located in rural Oregon and rural Northern California.18

In conclusion, Oregon FIRST successfully prepared participants for their internship year and solidified participants’ decisions about pursuing careers in rural practice where physician workforce shortages affect health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Cascades East Family Medicine Residency Program, Oregon Health & Science University School of Medicine and Provost’s Office, and the California Oregon Medical Partnership to Address Disparities in Rural Education and Health (COMPADRE) as part of the American Medical Association’s Reimaging Residency Initiative.

References

- Bingham CM, Crampton R. A review of prevocational medical trainee assessment in New South Wales. Med J Aust. 2011;195(7):410-412. doi:10.5694/mja11.10109

- Kilminster S, Zukas M, Quinton N, Roberts T. Preparedness is not enough: understanding transitions as critically intensive learning periods. Med Educ. 2011;45(10):1006-1015. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04048.x

- Minha S, Shefet D, Sagi D, Berkenstadt H, Ziv A. “See One, Sim One Do One” – A national pre-internship boot camp to ensure a safer “Student to Doctor Transition. PLoS One, 2016, 2; 11(3):e0150122.

- Lerner V, Higgins EE, Winkel A. Re-boot: simulation elective for medical students as preparation bootcamp for obstetrics and gynecology residency. Cureus. 2018;10(6):e2811. doi:10.7759/cureus.2811

- Scicluna HA, Grimm MC, Jones PD, Pilotto LS, McNeil HP. Improving the transition from medical school to internship - evaluation of a preparation for internship course. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):23. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-14-23

- Vairy S, Jamoulle O, Levy A, Carceller A. Transitioning from medical school to residency: evaluation of an innovative immersion rotation for PGY-1 paediatric residents. Paediatr Child Health. 2018;23(2):96-100. doi:10.1093/pch/pxx147

- The core entrustable professional activities for entering residencies. Association of American Medical Colleges. Accessed April 16, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/medical-education/cbme/core-epas

- Harris P, Snell L, Talbot M, Harden RM; International CBME Collaborators. Competency-based medical education: implications for undergraduate programs. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):646-650. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2010.500703

- Chang LL, Grayson MS, Patrick PA, Sivak SL. Incorporating the fourth year of medical school into an internal medicine residency: effect of an accelerated program on performance outcomes and career choice. Teach Learn Med. 2004;16(4):361-364. doi:10.1207/s15328015tlm1604_9

- Integrated medical school and family medicine residency. Michigan State University. Accessed December 6, 2020. https://chmfamilymedicine.msu.edu/teaching/scholarships/tip/

- James CV, Moonesinghe R, Wilson-Frederick SM, Hall JE, Penman-Aguilar A, Bouye K. Racial/ethnic health disparities among rural adults - United States. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(23):1-9. Published. 2012-2015;2017(Nov):17. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6623a1

- Skariah JM, Rasmussen C, Hollander-Rodriguez J, et al. Rural curricular guidelines based on practice scope of recent residency graduates practicing in small communities. Fam Med. 2017;49(8):594-599.

- Thach SB, Hodge B, Cox M, Parlier-Ahmad AB, Galvin SL. Cultivating Country Doctors: Preparing Learners for Rural Life and Community Leadership. Fam Med. 2018;50(9):685-690. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.972692

- World Population Review: Klamath Falls, Oregon Population 2021. Accessed August 13, 2020. https://worldpopulationreview.com/us-cities/klamath-falls-or-population

- All In Policy – Main Residency Match. National Residency Match Program. Accessed August 16, 2021. https://www.nrmp.org/all-in-policy/main-residency-match/

- All In Policy Exception Criteria and Request Form. National Residency Match Program. Accessed August 16, 2021. https://mk0nrmp3oyqui6wqfm.kinstacdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Exception-Form-2020.pdf

- Bauer MW, Gaskell G. (2000). Classical content analysis: a review. In: Qualitative Researching With Text, Image and Sound. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. pgs 132-152. doi:10.4135/9781849209731.n8

- Reimaging Residency Initiative. American Medical Association. Accessed November 17, 2020. https://www.ama-assn.org/education/improve-gme/ama-reimagining-residency-initiative?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIzJWCjZOK7QIVRRh9Ch2buwV3EAAYASAAEgKOnfD_BwE