Background and Objectives: Primary care clinicians are in a unique position to address intimate partner violence (IPV) in routine clinical practice. The purpose of this study was to improve clinician readiness to identify and manage IPV in four family medicine residency practice sites on the west side of Chicago by partnering with a local domestic violence organization.

Methods: Practice sites included three federally qualified health centers and one hospital-based office. Eligible clinicians included resident and faculty physicians, nurse practitioners, and certified nurse midwives. We assessed readiness using the validated Physician Readiness to Manage Intimate Partner Violence Survey (PREMIS). We used initial survey results (n=53, 73%) to develop a targeted clinician educational intervention by a community organization. We administered the PREMIS tool postintervention at 1 and 6 months, measuring perceived and actual knowledge, preparedness, and practice issues. We performed comparison statistics to assess aggregate change.

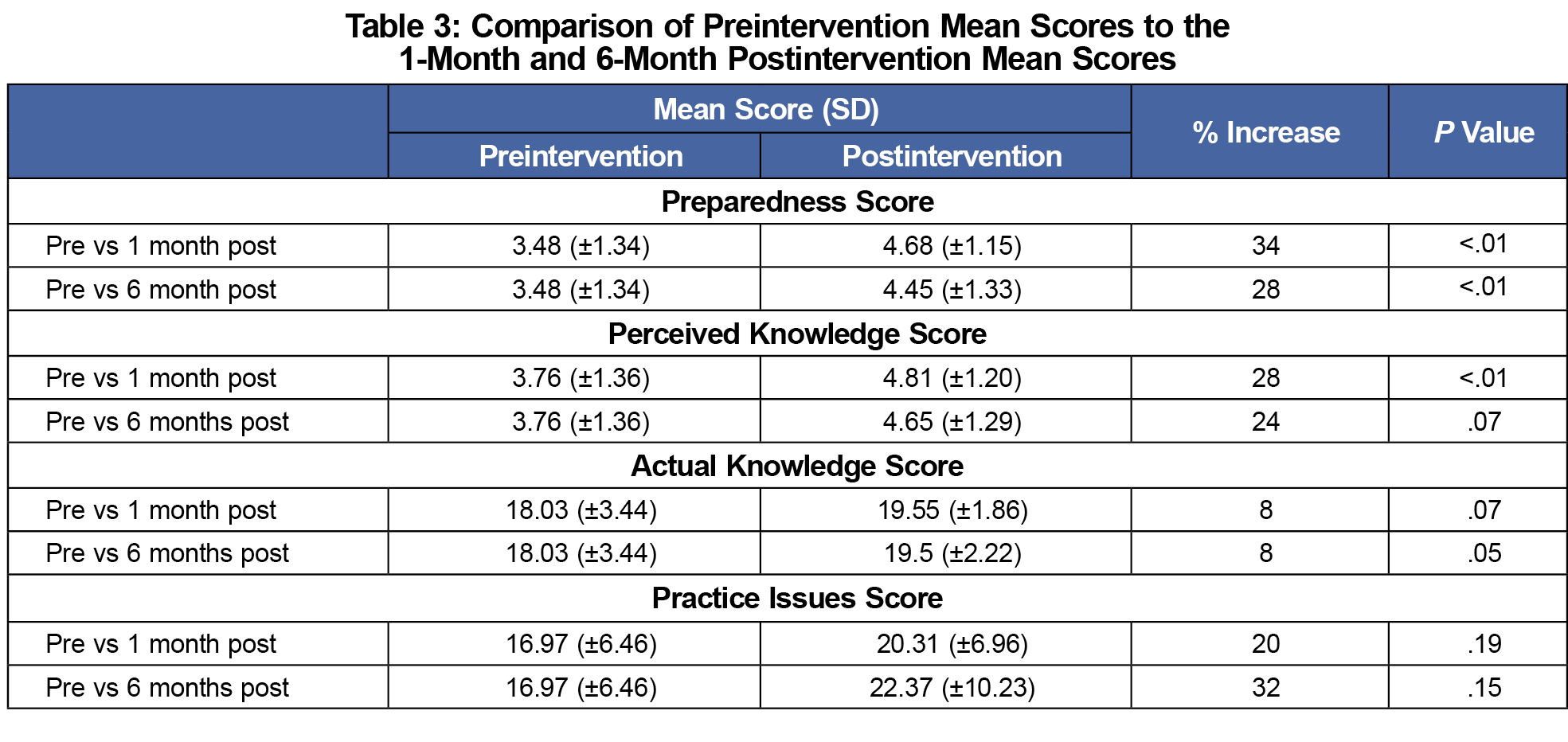

Results: PREMIS response rates were n=53 (72%), n=32 (47%), and n=36 (49%), for preintervention, 1, and 6 months postintervention, respectively. Mean clinician preparedness score improved significantly at 1 and 6 months (P<.001, P<.009). Mean self-perceived knowledge score improved significantly at 1 month (P<.001) and trended toward improvement at 6 months (P=.07). Actual knowledge trended toward improvement at 1 month (P=.07) and after 6 months (P=.05). Mean practice issues scores did not improve significantly.

Conclusions: Participation in a 45-minute targeted educational intervention improved clinician readiness to manage IPV. Collaborating with a community partner builds a relationship for further referrals and advocacy for patients.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is defined as “any behavior within an intimate relationship that causes physical, psychological, or sexual harm to those in that relationship.”1 Consequences beyond immediate harm to the victim include an increased incidence of chronic pain, sexually transmitted infections, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and suicide.2,3 Those affected by IPV often do not openly disclose issues around personal safety unless directly asked.4 However, research demonstrates that victims often access medical services for related concerns such as chronic pain or depression.5 Despite the availability of abbreviated screening tools, such as the Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) and the more gender-neutral “Hurt, Insult, Threaten, Scream” (HITS) surveys, adoption of routine screening in clinical practice is not universal.6,7 Barriers to routine screening may include lack of clinician knowledge, experience, and time.8-11

With over 299 million primary care office visits per year in the United States, primary care clinicians have the opportunity to play a pivotal role in the screening and management of IPV.12 The American Academy of Family Physicians and the United States Preventive Services Task Force both recommend that clinicians routinely screen for IPV in women of reproductive age and offer those who screen positive with referral services.12,13 The Physician Readiness to Manage Intimate Partner Violence Survey (PREMIS) is a 67-item, comprehensive screening tool developed to assess the preparedness of physicians to manage IPV and to evaluate the effectiveness of physician IPV education and training. PREMIS demonstrates strong internal reliability and validity to evaluate (1) perceived knowledge, (2) actual knowledge, (3) preparedness, and (4) practice issues surrounding IPV.15 Studies using this tool have found similarities as most clinicians report a lack of knowledge, skills, and confidence to address IPV routinely.16-18 The purpose of this study was to assess clinicians’ readiness to identify and manage IPV at baseline and identify potential change after exposure to a targeted educational intervention prepared by a community organization with expertise in management.

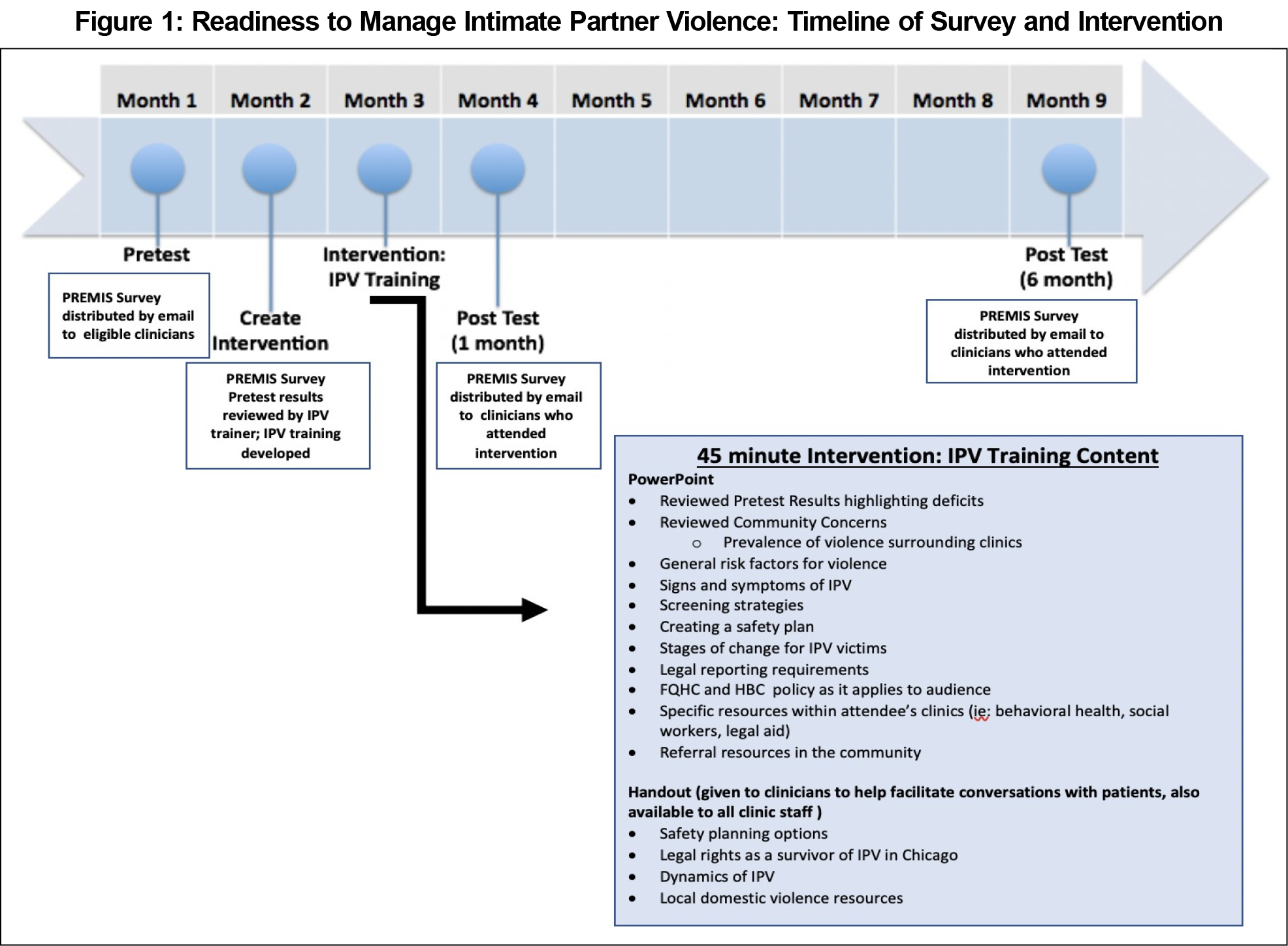

Study sites included four residency training clinics at a community-based urban family medicine residency in Chicago: three federally qualified health center (FQHC) practices (Sites A, B, and C) and a non-FQHC hospital-based practice (Site D). Resident and faculty physicians, nurse practitioners, and midwives who actively practiced at Sites A-D were eligible for participation. We distributed the PREMIS tool by email to all participants at baseline, 1 month and 6 months postintervention. Clinicians were given a 2-week time period to complete the survey, with a total of three reminders for each survey (see Figure 1 for a timeline of survey and educational intervention implementation).

We analyzed data using the PREMIS syntax and codebook provided by Short et al. We calculated means and standard deviations for each of the outcome variables of interest and conducted unpaired t tests to assess differences between intervals of administration of the survey. Clinician response rates for baseline, 1 month, and 6 months postintervention surveys were aggregated values stratified by clinician type, and we assessed aggregate change. We analyzed all data using Stata v13.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). This project was determined to be exempt from institutional review board review.

Researchers collaborated with an IPV trainer from a community organization that was a referral source for Sites A-D. Utilizing baseline data from the PREMIS, the IPV trainer prepared a targeted 45-minute educational training intervention and comprehensive handout (specific community resources, dynamics of IPV, legal rights, safety planning options). Specific content in the intervention is outlined in Figure 1. Clinicians had the opportunity to attend the intervention at three separate days and times. This intervention was given at regularly scheduled clinic practice management times that had built-in space available for guest lectures from the community or hospital.

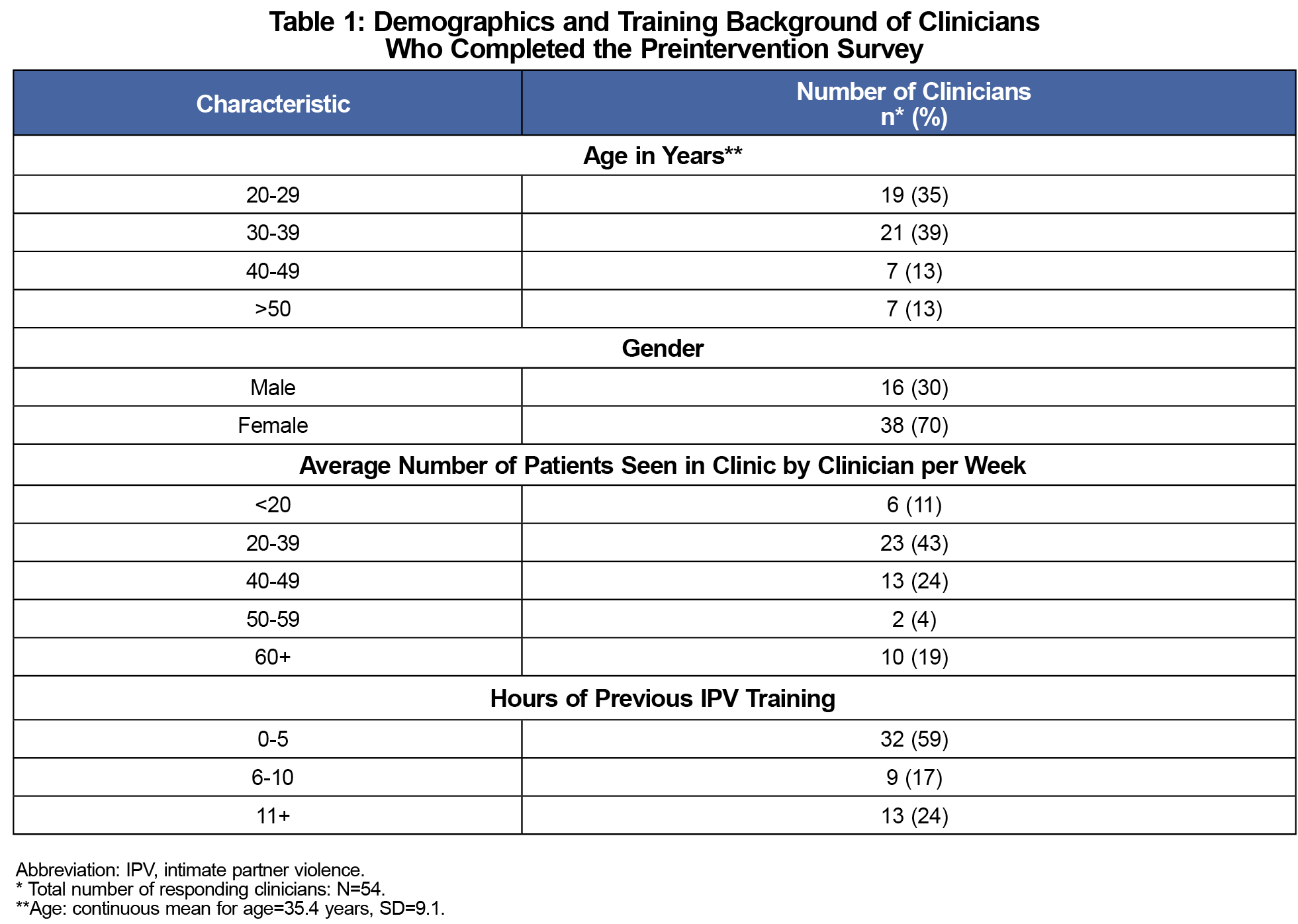

Study participants included a total of 73 clinicians: 58 family physicians (27 resident and 31 faculty physicians), six midwives, and nine nurse practitioners (Table 2). Clinicians at Sites A-C represented 77% of the study population, whereas the remaining 23% of clinicians were based at Site D. Clinicians who did not attend the training were not included in the postintervention surveys.

Survey results demonstrated a significant improvement in the mean preparation score both at 1 month (P<.001) and 6 months (P=.009) postintervention (Table 3). Mean scores for clinician self-perceived knowledge improved at 1 month postintervention (P=.001), but only trended towards improvement at 6 months postintervention (P=.07). The mean actual knowledge score trended toward improvement 1 month postintervention (P=.07), with improvement becoming statistically significant 6 months postintervention (P=.05). There was no significant change in the mean practice issue score, although there was a trend toward improvement at both 1 month and 6 months postintervention.

This study demonstrates that a brief, clinician-targeted intervention facilitated by a community partner can contribute to improve clinician readiness to recognize and initiate steps in addressing IPV in clinical practice. Strengths of this study include the customization of the educational intervention through use of the preintervention PREMIS results, as well as emphasis on specific, actionable clinic policies and procedures, are believed to have contributed to clinicians’ increased confidence. Given that clinicians have limited capacity for specialized IPV training, this process of preassessment and focused intervention could be adapted to other settings and achieve positive results.10,11 Regardless of the clinical practice setting (private, FQHC, employed), practices should seek out existing organizations within their community for resources surrounding IPV training and services for patients. Additionally, using the validated tool PREMIS, to evaluate clinician readiness to manage IPV provides another strength to future practices.

Limitations to this study include the possibility that the participants consisted of predominantly young, early-career female physicians, although more women graduate from family medicine programs than men. Additionally, decreased attendance at the training could have been due to those with lack of interest in IPV. Using aggregated data as opposed to linked responses from clinicians did not allow us to draw comparison of individual clinicians’ preparedness over time. We also recognize potential scrutiny over a single 45-minute training as our intervention, although this opened a relationship with a community partner that extended beyond one session, as it made this organization visible, and opened communication for clinicians and staff as patient resources.

We can equip clinicians with knowledge and confidence to manage IPV, but ultimately there is a need for more approaches that connect patients in a timely way with resources in their community. Building clinician advocacy skills and teaching the importance of community partnerships is a crucial lesson for physicians in training.20 Future research should aim to test other comprehensive approaches to preparing clinicians and clinics to better address IPV in routine care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Colleen Sutkus, Director of Training and Education at Sarah’s Inn, a comprehensive domestic violence community organization in Oak Park, Illinois. The authors also thank Naomi Nemoto, MPH, who served as the statistician for this project.

Presentations: This study was presented at the STFM Conference on Practice Improvement, December 3-6, 2015, in Dallas, Texas; the STFM Annual Spring Conference April 30-May 4, 2016, in Minneapolis, Minnesota; and at the Illinois Academy of Family Physicians’ Resident Scholarly Works Webinar, May 6, 2016.

References

- Intimate Partner Violence and Alcohol Fact Sheet. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/factsheets/ft_intimate.pdf. Accessed August, 2020.

- Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, Chen J, Stevens MR. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 Summary Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/pdf/NISVS_Report2010-a.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed August, 2020.

- Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002;359(9314):1331-1336. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08336-8

- Morse DS, Lafleur R, Fogarty CT, Mittal M, Cerulli C. “They told me to leave”: how health care providers address intimate partner violence. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(3):333-342. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2012.03.110193

- Davies R, Lehman E, Perry A, McCall-Hosenfeld JS. Association of intimate partner violence and health-care provider-identified obesity. Women Health. 2016;56(5):561-575. doi:10.1080/03630242.2015.1101741

- Brown JB, Lent B, Schmidt G, Sas G. Application of the Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) and WAST-short in the family practice setting. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(10):896-903.

- Sherin KM, Sinacore JM, Li XQ, Zitter RE, Shakil A. HITS: a short domestic violence screening tool for use in a family practice setting. Fam Med. 1998;30(7):508-512.

- Gutmanis I, Beynon C, Tutty L, Wathen CN, MacMillan HL. Factors influencing identification of and response to intimate partner violence: a survey of physicians and nurses. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(1):12. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-12

- Sprague S, Madden K, Simunovic N, et al. Barriers to screening for intimate partner violence. Women Health. 2012;52(6):587-605. doi:10.1080/03630242.2012.690840

- Dicola D, Spaar E. Intimate partner violence. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(8):646-651.

- Feder G. Beyond identification of patients experiencing intimate partner violence. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(8):600-605.

- Policies - Intimate Partner Violence. American Academy of Physicians. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/intimate-partner-violence.html. Published 2019. Accessed January 10, 2021.

- Intimate Partner Violence: Final Recommendation Statement. US Preventive Services Task Force. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/intimate-partner-violence-and-abuse-of-elderly-and-vulnerable-adults-screening. Published October 23, 2018. Accessed January 10, 2021.

- Rao A, Shi Z, Ray KN, Mehrotra A, Ganguli I. National trends in primary care visit use and practice capabilities, 2008-2015. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(6):538-544. doi:10.1370/afm.2474

- Short LM, Alpert E, Harris Jr JM, Surprenant ZJ. A tool for measuring physician readiness to manage intimate partner violence. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(2):173-180. e119. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2005.10.009

- Clark CJ, Renner LM, Logeais ME. Intimate partner violence screening and referral practices in an outpatient care setting. J Interpers Violence. 2017;0886260517724253. doi:10.1177/0886260517724253

- Barnard M, West-Strum D, Yang Y, Holmes E. Evaluation of a tool to measure pharmacists’ readiness to manage intimate partner violence. Pharmacy (Basel). 2018;6(3):66. doi:10.3390/pharmacy6030066

- Carlson M, Kamimura A, Al-Obaydi S, Trinh HN, Franchek-Roa K. Background and clinical knowledge of intimate partner violence: a study of primary care residents and medical students at a United States medical school. Health Equity. 2017;1(1):77-82. doi:10.1089/heq.2017.0008

- Active Physicians by Sex and Specialty, 2015. Association of American Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/active-physicians-sex-and-specialty-2015, Accessed January 10, 2021.

- McCloskey LA, Lichter E, Williams C, Gerber M, Wittenberg E, Ganz M. Assessing intimate partner violence in health care settings leads to women’s receipt of interventions and improved health. Public Health Rep. 2006;121(4):435-444. doi:10.1177/003335490612100412

There are no comments for this article.