Background and Objectives: Multilevel factors drive health disparities experienced by sexual and gender minority (SGM) populations. We developed a 3-hour symposium focusing on care for SGM youth to address this. The symposium was a free, extracurricular event open to the public, with an emphasis on health professional students and providers from all disciplines and involved interprofessional didactic and interactive components.

Methods: Participants completed optional retrospective pre/postsurveys immediately and 10 months postsymposium. Surveys contained Likert-scale questions addressing five indicators of symposium effectiveness related to knowledge, confidence, and comfort in providing care for SGM populations. We used 1-tailed paired t tests to evaluate the effectiveness of the symposium, and analysis of variance tests to compare differences by professional role.

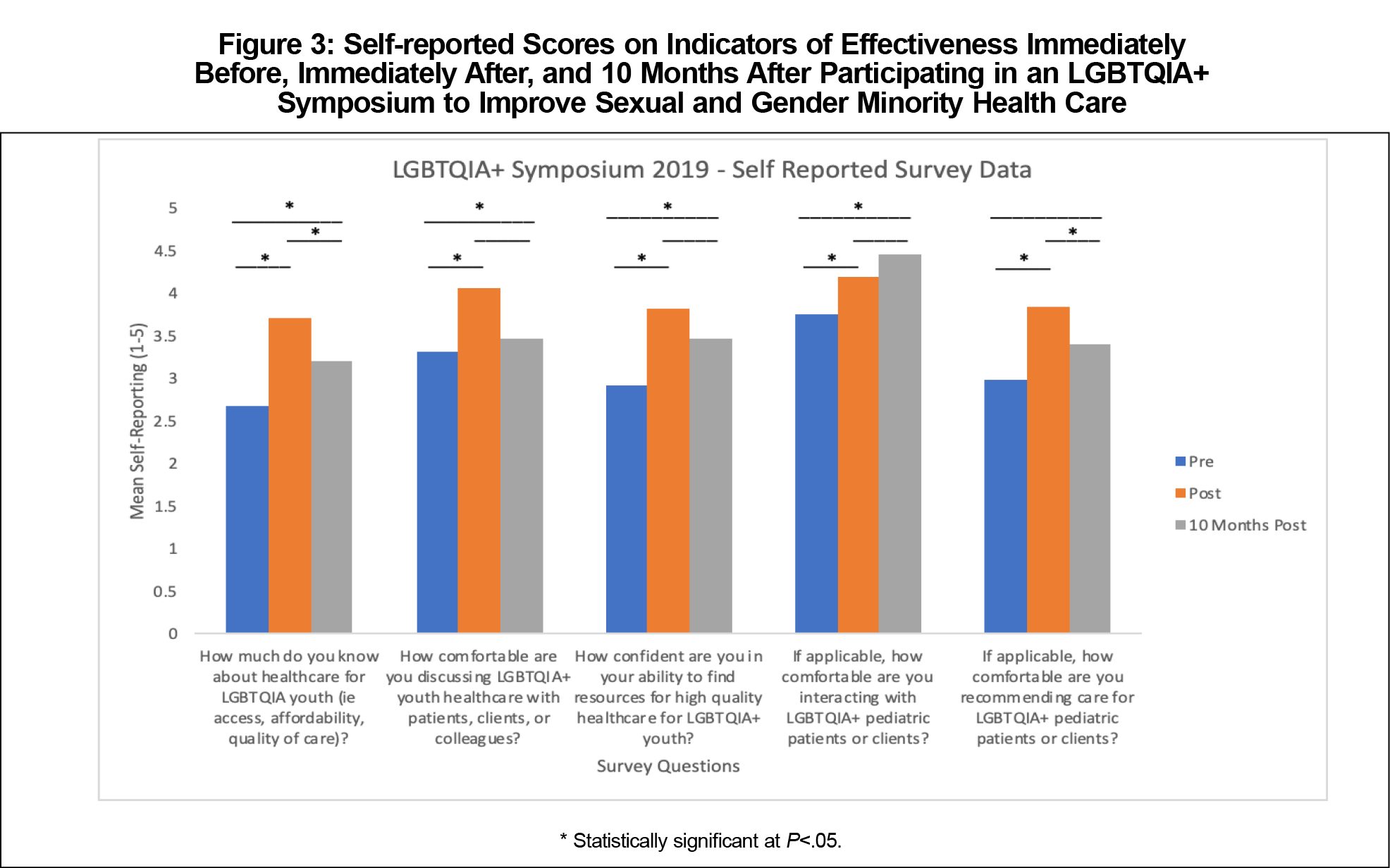

Results: Of 208 individuals who attended the symposium, 67 completed the initial survey, and 23 completed the 10-months postsymposium survey. Participants reported significantly higher (P<.001) scores across all five measures of effectiveness from pre- to immediately postsymposium, and remained at significantly higher (P<.05) scores across all measures from presymposium to 10 months postsymposium, except for comfort recommending care for SGM pediatric patients or clients.

Conclusion: Results suggest that the symposium improved participants’ perceived effectiveness in serving SGM pediatric patients, although selection bias is a concern. Dissemination of educational approaches that incorporate interprofessional didactic and active learning components may help improve workforce capacity to improve SGM health.

Sexual and gender minority (SGM) individuals experience health disparities relative to their nonSGM peers.1,2 SGM includes lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and questioning, intersex, asexual, and gender diverse (LGBTQIA+) individuals. These disparities are driven by multilevel factors including stigma, social inequity, and lack of awareness among health care providers.3

Clinicians have an important role in mitigating health disparities experienced by SGM youth, particularly in addressing bullying and its negative sequelae and offering suggestions for constructive responses.4 Research suggests that medical trainees lack opportunities to develop skills for effectively treating and counseling these patients,5 with limited curricular hours focused on SGM health.6,7 Undergraduate medical education represents an opportune time for advancing these competencies as trainees develop foundational clinical and communication skills. Here, we describe a student-driven LGBTQIA+ symposium with its immediate and lasting impacts.

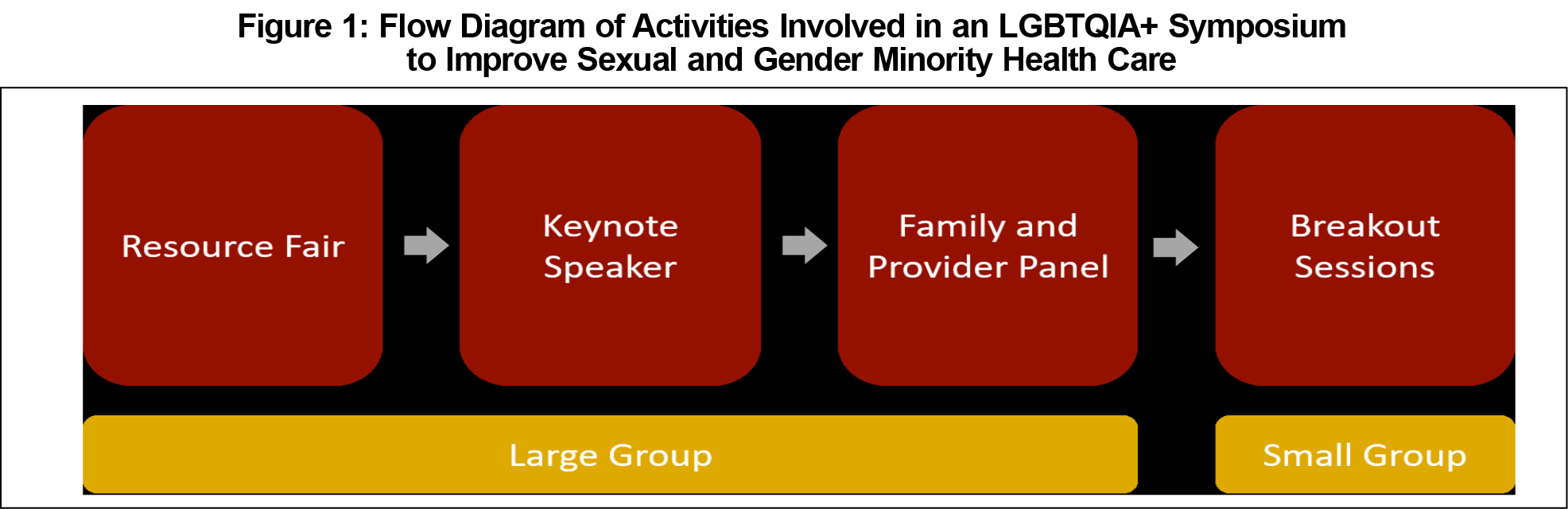

The LGBTQIA+ symposium was a free extracurricular event open to the public, with an emphasis on health professional students and providers across disciplines as well as community members. Two hundred-eight individuals attended, including 101 students, 48 health care providers, and 59 community members. The symposium included a resource fair, keynote speaker, patient and provider panel, and breakout sessions (Figure 1, Appendix A).8 The didactic components of the symposium were followed by small-group discussion breakout sessions that leveraged active learning principles, which have been associated with longer-term information retention.9 Break-out sessions centered around a 3-part interactive case that followed a hypothetical SGM adolescent through several primary care appointments from initial presentation to management options, providing exposure to the considerations and challenges involved in providing gender-affirming care to SGM youth. Health professionals experienced in working with SGM populations and family members of SGM individuals facilitated the interprofessional group sessions using a semistructured discussion guide (Appendix B).10

Data Collection

We administered two retrospective pre/post surveys11 to examine the effectiveness of symposium participation at increasing proficiency in SGM youth health topics. The first was an optional, anonymous survey immediately following the symposium, asking participants to retrospectively assess their knowledge and comfort before the symposium as well as after, hereinafter the “postsymposium survey.” A follow-up survey was sent electronically to participants 10 months after the symposium with one follow-up reminder. The symposium’s effectiveness was operationalized based on five indicators of competence in caring for SGM populations:

- Knowledge about SGM populations,

- Comfort in discussing their health care needs,

- Confidence in finding resources,

- Comfort in interacting with SGM populations,

- Comfort in recommending care for SGM populations.

Data Analysis

We conducted 1-tailed, paired t tests to evaluate the effectiveness of the symposium, and analysis of variance tests to compare differences by professional role. As these surveys were anonymous, the project was determined not to constitute research involving human subjects, and thus exempt from review by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board.

Postsymposium Survey

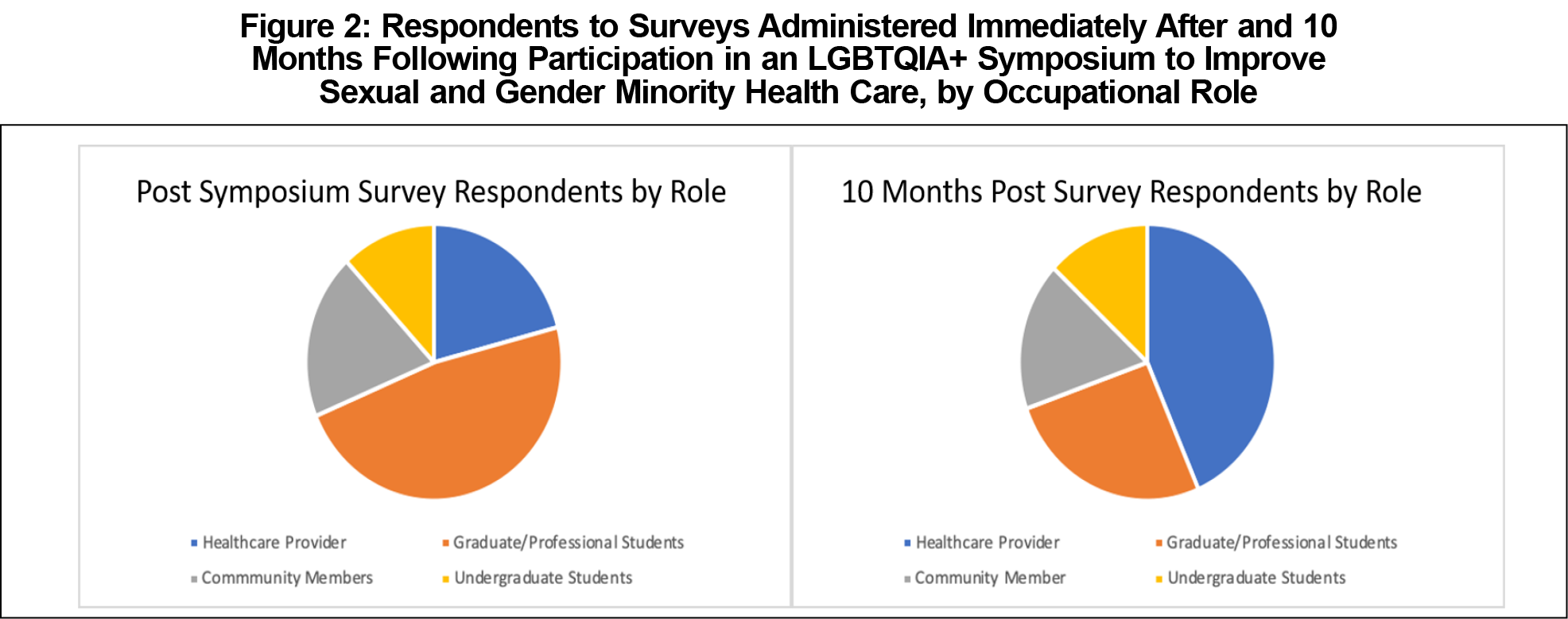

Two hundred-eight individuals attended the symposium, of whom 67 (32%) responded to the initial postsymposium survey. Respondents included graduate students (48%), undergraduate students (12%), health care providers (21%), and community members (19%, Figure 2).

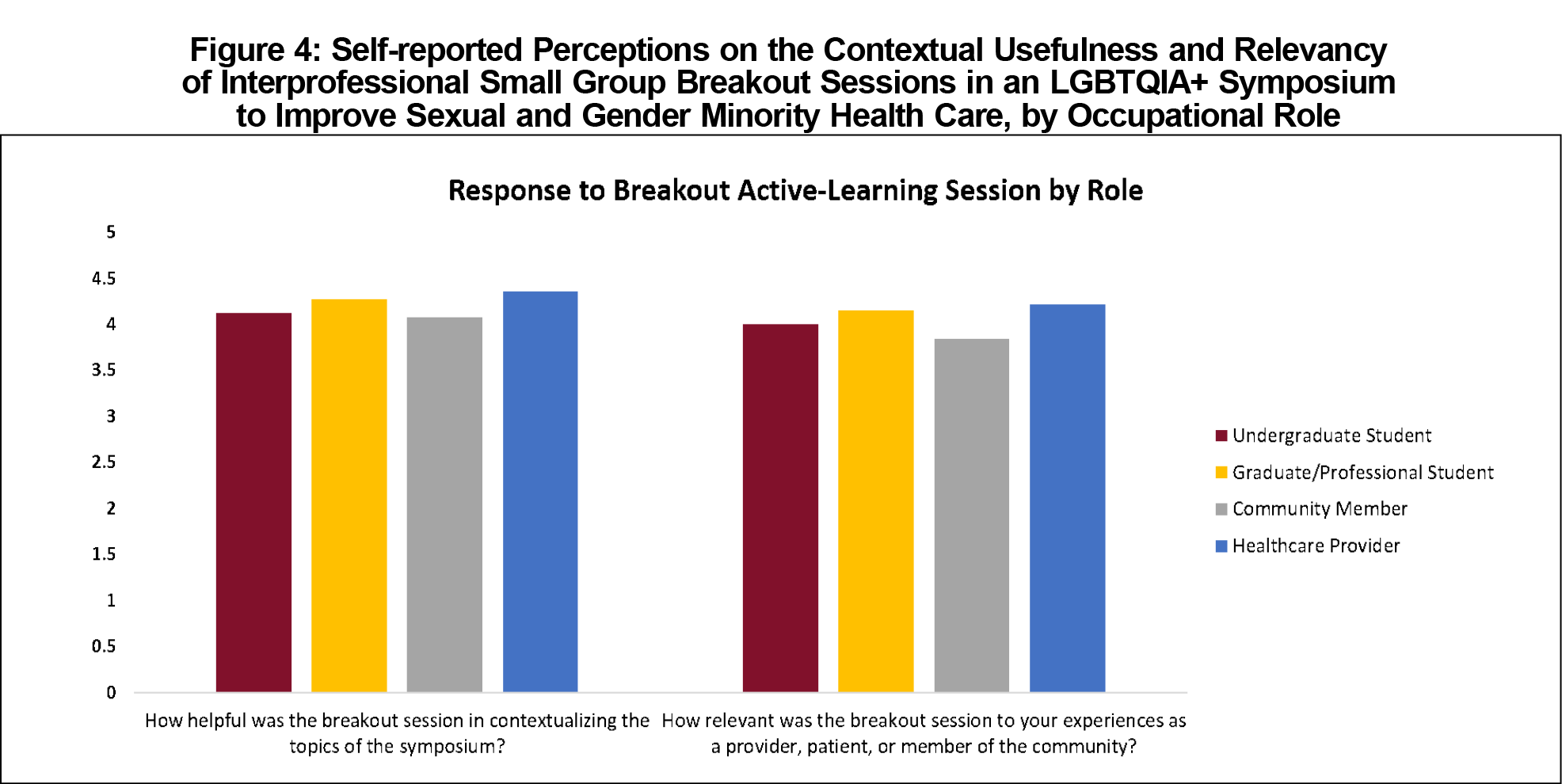

Overall, participants reported significantly higher (P<.001) scores across all five measures of effectiveness from pre- to postsymposium (Figure 3). However, when respondents were grouped by stage of training, undergraduates and community members did not report significantly higher scores in comfort in interacting with LGBTQIA+ pediatric patients or clients. There were no statistically significant differences by professional role in either value and relevance or contextualization of the symposium’s active-learning components (Figure 4).

Follow-up Survey

Ten months after the symposium, we sent a follow-up survey to attendees, of whom 23 individuals (11%) responded. Respondents included graduate students (26%), undergraduate students (13%), health care providers (43%), and community members (17%, Figure 2).

Participants continued to report significantly higher (P<.05) scores across all measures of effectiveness compared to prior to the symposium, except for comfort recommending care for LGBTQIA+ pediatric patients or clients (Figure 3). From immediately postsymposium to 10 months postsymposium there was a significant (P<.05) decrease in self-reported knowledge about LGBTQIA+ health care and comfort recommending care for LGBTQIA+ patients and clients (Figure 3).

Immediately after the symposium, participants reported significantly higher scores across all five measures of effectiveness. These changes persisted over time, with the exception of self-reported knowledge, which decreased, possibly due to knowledge decay.

With an initial 32% response rate and an 11% follow-up response rate, these data are limited by selection bias, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions about the symposium’s effectiveness, especially over time. The occupational demographics of respondents also differed between surveys, with more initial respondents being graduate or professional students, but more follow-up respondents being health care providers (Figure 2). This selection bias may be explained by increased motivation to respond among providers more experienced in or passionate about SGM health care.

Other limitations include self-report surveys, which could introduce sampling and social desirability biases. It is also unclear whether improved knowledge and comfort translates to meaningful changes in behavior or patient outcomes. Further, respondents’ perceptions of the symposium may have been influenced by a halo effect,12 although the use of a 10-month follow-up survey mitigates this concern. Despite these limitations, this study contributes to the evidence on educational strategies to improve care for SGM populations. Consistent with other studies,13,14 the improved comfort and knowledge in caring for these communities persisted for months following participation. Future studies could leverage larger sample sizes, address training needs concerning more granular SGM populations (eg, intersex individuals), and measure SGM patient outcomes.

This data, coupled with growing evidence on SGM health disparities, highlight a gap in medical education. While curricular change is optimal,2 many medical students are limited in their ability to make immediate curricular changes due to time needed for curriculum development and institutional bureaucracy. Additionally, the symposium format allows for participation by practicing clinicians as well as community members. As the medical community works toward more substantive reforms to medical education curricula, the current report documents the benefits and provides a template for a half-day symposium that can be considered and adapted to support health care providers and community members enhance their knowledge of SGM health.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge speakers Dr Erica Anderson, Leslie Lagerstrom, Sam Lagerstrom, Marsha Pennington, Dr Adam Foss, Dr Diane Berg, and Dr Robert Englander.

Symposium Sponsors: Professional Student Government, Office of Minority & Diversity, University of Minnesota Center for Allied Health Professions; University of Minnesota Earl E. Bakken Center for Spirituality and Healing; University of Minnesota School of Physical Therapy; University of Minnesota Medical School; University of Minnesota School of Nursing; University of Minnesota School of Dentistry; University of Minnesota Student Unions and Activities Grants Initiatives; and the National Center for Gender Spectrum Health.

Organizations: RECLAIM, JustUs Health, YAP UMN, LGBT Therapists, Bisexual Organizing Project (BOP), Harbor Clinic, Planned Parenthood, OutFront

Facilitators: Matt Armfield, MD, MAEd; Rachel Becker-Warner, PsyD; Adam Foss, MD; Ejay Jack, MSW, MPA; Alex Kovic, MD; Leslie Lagerstrom, Nersi Nikakhtar, MD; Marsha Plartington, MA, LADC; Katherine Spencer, PhD; Corri Stuyvenberg, MA, PT, DPT; Andrea Westby, MD

Case Review: Kate Shafto, MD

Volunteers: Kylie Blume, Anna Dovre, Sara Lederman, Christina Daragan, Lily Ward, Ruth Eckel, Rachael Gotlieb, and Hodan Abdi

References

- Valdiserri RO, Holtgrave DR, Poteat TC, Beyrer C. Unraveling health disparities among sexual and gender minorities: a commentary on the persistent impact of stigma. J Homosex. 2019;66(5):571-589. doi:10.1080/00918369.2017.1422944

- Ard KL, Makadon HJ. Improving the Healtchare of LGBT People : Understanding and Eliminating Health Disparities. Boston, MA: National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center; 2012.

- Rowe D, Ng YC, O’Keefe L, Crawford D. Providers’ attitudes and knowledge of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health. Fed Pract. 2017;34(11):28-34.

- Earnshaw VA, Bogart LM, Poteat VP, Reisner SL, Schuster MA. Bullying among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016;63(6):999-1010. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.004

- White W, Brenman S, Paradis E, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patient care: medical students’ preparedness and comfort. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27(3):254-263. doi:10.1080/10401334.2015.1044656

- Honigberg MC, Eshel N, Luskin MR, Shaykevich S, Lipsitz SR, Katz JT. Curricular time, patient exposure, and comfort caring for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients among recent medical graduates. LGBT Health. 2017;4(3):237-239. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2017.0029

- Moll J, Krieger P, Moreno-Walton L, et al. The prevalence of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health education and training in emergency medicine residency programs: what do we know? Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(5):608-611. doi:10.1111/acem.12368

- So M, Elkin B, Beck-Esmay K, Chu K, Donlon T. Description of Symposium Components. STFM Resource Library. 2018. https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/university-of-minnesota-lgbtqia-sy?CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a&tab=librarydocuments. Accessed March 2, 2021.

- Torralba KD, Doo L. Active Learning Strategies to Improve Progression from Knowledge to Action. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2020;46(1):1-19. doi:10.1016/j.rdc.2019.09.001

- So M, Elkin B, Beck-Esmay K, Chu K, Donlon T. Interprofessional Case Study with Facilitator’s Guide. STFM Resource Library. 2018. https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/university-of-minnesota-lgbtqia-sy?CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a&tab=librarydocuments. Accessed March 1, 2021.

- Bhanji F, Gottesman R, de Grave W, Steinert Y, Winer LR. The retrospective pre-post: a practical method to evaluate learning from an educational program. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(2):189-194. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01270.x

- Keeley JW, English T, Irons J, Henslee AM. Investigating halo and ceiling effects in student evaluations of instruction. Educ Psychol Meas. 2013;73(3):440-457. doi:10.1177/0013164412475300

- Dubin SN, Nolan IT, Streed CG Jr, Greene RE, Radix AE, Morrison SD. Transgender health care: improving medical students’ and residents’ training and awareness. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2018;9:377-391. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S147183

- Sawning S, Steinbock S, Croley R, Combs R, Shaw A, Ganzel T. A first step in addressing medical education Curriculum gaps in lesbian-, gay-, bisexual-, and transgender-related content: The University of Louisville Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Certificate Program. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2017;30(2):108-114. doi:10.4103/efh.EfH_78_16

There are no comments for this article.