Introduction: Interacting with patients in a manner that furthers self-responsibility for health is an important skill for primary care clinicians. Motivational interviewing (MI) is such an approach to patient engagement, but it remains to be more widely implemented. In a program training health professionals and health professions students in MI, we examined posttraining attitudes and intentions regarding the utilization of MI. Of particular interest was how posttraining intentions were associated with self-reported action 1 month later.

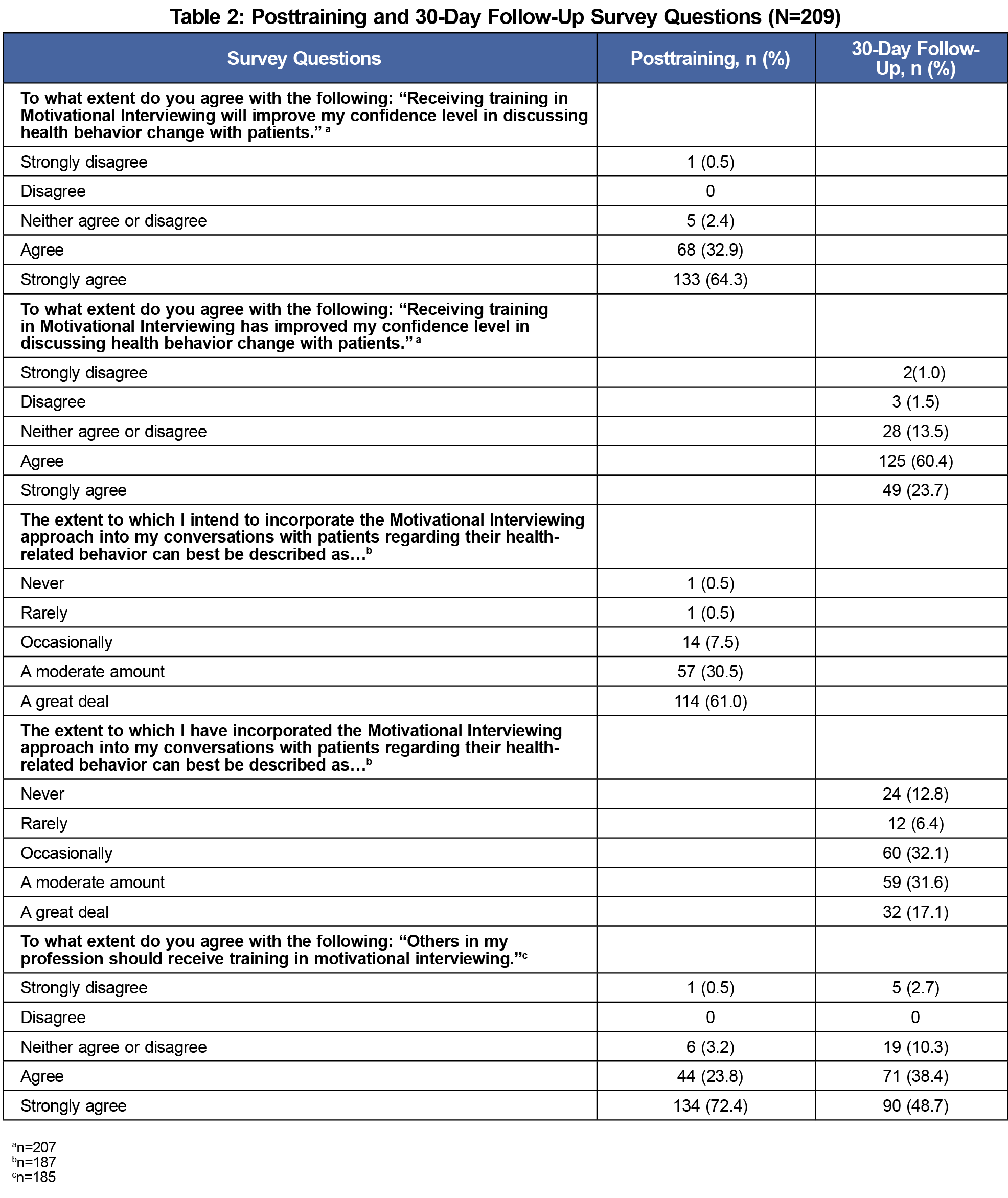

Methods: We obtained immediate posttraining and 30-day follow-up data from 209 participants regarding intent to utilize the MI approach (self-reported implementation at the follow-up interval), impact on confidence with patient interaction, and perceived importance of the training. We analyzied frequencies and percentages for all categorical/ordinal variables to describe the participants and the survey question responses.

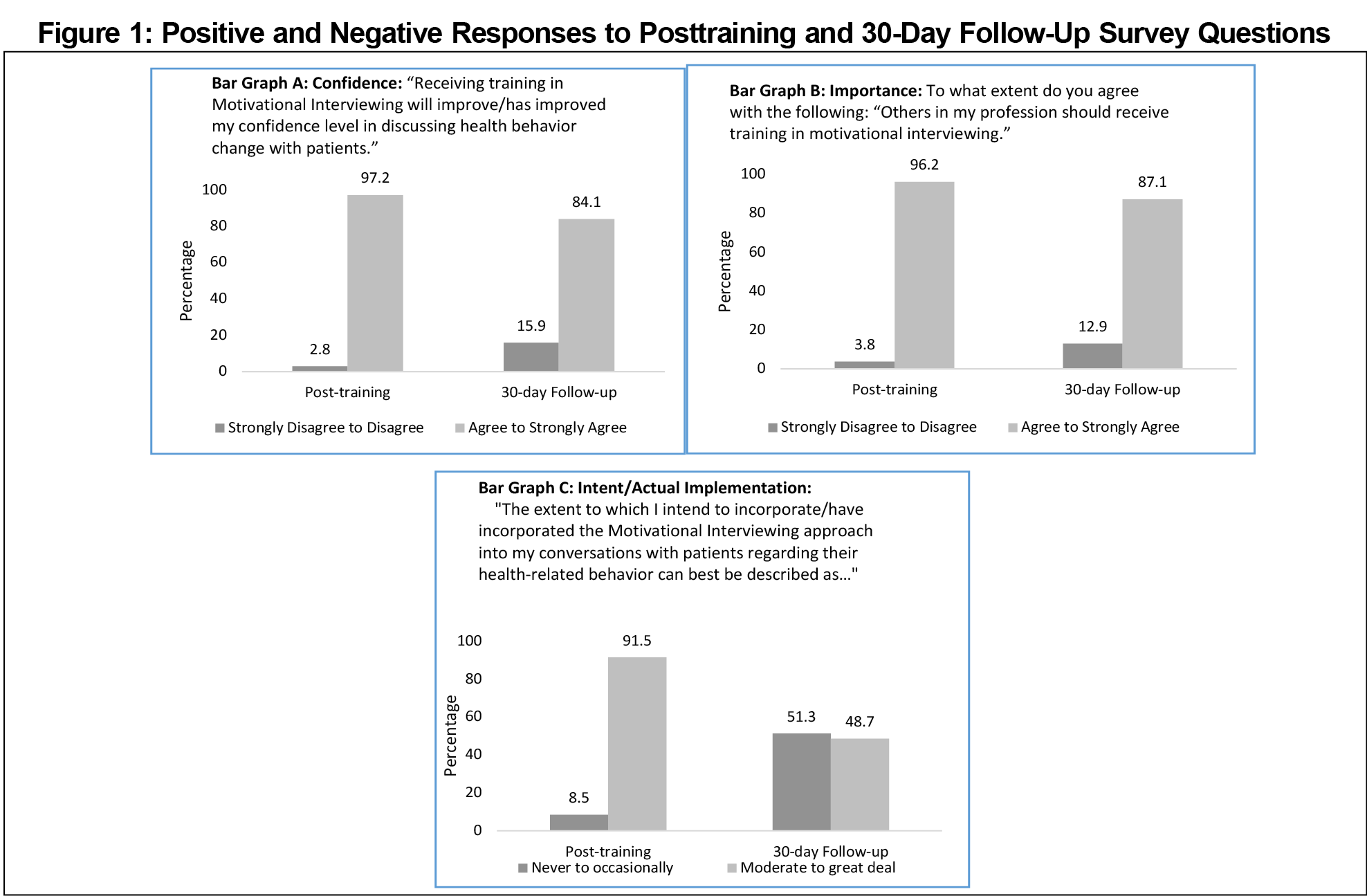

Results: While 91.5% of participants intended to incorporate MI into their approach with patients (to a moderate or great extent) at posttraining, only 48.7% reported that they had actually implemented the MI approach (to a moderate or great extent) 30 days later. However, another 32.1% indicated that they had occasionally utilized MI. Attitudes toward the importance of MI training and the impact of training on confidence remained strong over the 30 days.

Conclusion: Achieving more widespread implementation of the MI approach in the primary care setting is likely to be less dependent on convincing clinicians about its importance for patient engagement, but rather on the translation of intent to actual practice and implementation.

Morbidity and mortality in the United States is largely due to chronic illness; approximately 60% of adults have at least one chronic condition and over 40% have two or more.1 Patient ownership for their health is important for minimizing morbidity and premature mortality.2 Interacting with patients in a manner that fosters such responsibility is a critical skill for primary care clinicians, as patient behavior contributes more to health outcomes than does clinical care itself.3,4

Motivational interviewing (MI) is an approach to patient engagement first described in 1983,5 and is defined as “a collaborative conversation style for strengthening a person’s own motivation and commitment to change.”6 With MI, the physician facilitates patient exploration of potential reasons for healthy behavior change in the context of what is important to the patient, rather than the physician directly telling the patient what to do. MI is commonly more effective than other approaches to patient engagement and health behavior change,7,8 and can be effectively taught to medical students and residents,9,10 as well as primary care providers.11,12

In spite of the extensive literature supporting MI’s effectiveness, there is also evidence that it is not widely implemented, especially in the absence of ongoing feedback or coaching sessions.13 A systematic review found that the use of MI by practitioners in the substance misuse treatment arena—the setting in which MI was developed—was not consistently sustained after MI training.14 A recent study examining shared decision-making in primary care found that the patient’s agenda was elicited in only 36% of encounters.15 Eliciting a patient’s concerns, thoughts, and feelings are fundamental to trust-building and the MI approach.

In a program training health professionals and health professions students in MI and two specific applications of MI, we examined posttraining attitudes and intentions regarding the utilization of MI, both at the completion of the training and thirty days later. Of particular interest was how posttraining intentions were associated with self-reported action 1 month later.

As part of a regional educational effort, health professionals and health professions students were invited to participate in a training module (1-3 hours in length) that focused on MI and how MI is utilized in SBIRT (Screening, Brief Intervention, Referral to Treatment, https://www.samhsa.gov/sbirt) and PRESTO (Promoting Engagement for the Safe Tapering of Opioids, a protocol in development by the authors). Twenty-six modules were conducted in regional health systems’ facilities or area universities. The makeup of participants at each training event varied upon the settings; participating health professionals predominantly worked in primary care settings. Participants completed a posttraining survey (PTS) and were requested to subsequently complete a 30-day follow-up survey (30 DS). Our protocol was granted an exemption by our university institutional review board.

The PTS included three questions: intent to utilize the MI approach, perceived impact of learning the approach on one’s confidence, and belief that others in one’s profession should receive such training. The 30 DS included the same questions, with the exception that the question about intention was replaced with self-reported implementation.

We analyzed data using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC); we conducted frequencies and percentages for all categorical/ordinal variables to describe the participants and the survey question responses. We conducted McNemar’s test to examine changes in responses; we used α<.05.

A total of 408 participants completed one of the training modules and the PTS; 209 of these (51.2%) returned a 30 DS. There were no significant differences in PTS responses between participants who did or did not complete the 30 DS (P=.33, .22, .82 for intent, impact, and belief, respectively). Therefore, we describe data from the 209 participants completing both the PTS and 30 DS. There were no significant survey response differences based upon length of the training module. Further details of the participants are included in Table 1.

Immediately posttraining, 91.5% of participants intended to incorporate MI into their approach with patients to a moderate or great extent. Over 96% agreed or strongly agreed that receiving training in MI would improve their confidence level in discussing health behavior change with patients, and 96.2% agreed or strongly agreed that others in their profession should receive training in MI. Thirty days later, corresponding percentages for confidence and importance of training were 84.1% (13.1% decrease, P<.0001) and 87.1% (9.1% decrease, P=.0002) respectively, indicating some endurance of confidence and perceived importance. Only 48.7% (42.8% decrease, P<.0001) reported that they had actually implemented the MI approach to a moderate or great extent. Students, compared to professionals, were less likely to implement to a moderate or great extent (35.1% vs 60.4%, P=.0004). However, 32.1% of participants did indicate that they had occasionally utilized MI, albeit not as extensively as originally intended (Table 2, Figure 1).

Study participants indicated that training in MI is important to learn and to improve their confidence. Immediately after training, their intent to implement the approach was strong. Approximately 30 days later, however, the self-reported degree of implementation of the approach was discrepant with the posttraining intent.

In many respects, our results are not surprising given that implementation of the MI approach requires commitment and practice, and that for many health professionals it has not become second nature. Furthermore, posttraining intentions are not as predictive of subsequent behavior as would be more specific intentions, such as implementation intentions,16-18 which are marked by precise plans, such as “If this happens, then I will do…”

An important limitation of our study is that the MI training was a single module; substantially more training and practice are considered necessary to achieve proficiency with MI. Another study limitation is that our data were self-reported.

Achieving widespread implementation of the MI approach in primary care is less a matter of convincing clinicians about its importance, but rather of translation of intent into actual implementation and ongoing practice. This will likely require more intensive training, skills practice, coaching and feedback,13 specific implementation intentions,19 and perhaps incentives for busy clinicians to invest the time necessary for this endeavor.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This project was supported by the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services Grant #1900741.

References

- Buttorff C, Ruder T, Bauman M. Multiple chronic conditions in the United States. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation; 2017. doi:10.7249/TL221

- Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):207-214. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1061

- Kaplan RM. Behavior change and reducing health disparities. Prev Med. 2014;68:5-10; Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.04.014

- Kaplan RM, Milstein A. Contributions of health care to longevity: A review of 4 estimation methods. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(3):267-272. doi:10.1370/afm.2362

- Miller WR. Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers. Behav Psychother. 1983;11(2):147-172. doi:10.1017/S0141347300006583

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. New York: Guilford; 2013.

- VanBuskirk KA, Wetherell JL. Motivational interviewing with primary care populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Behav Med. 2014;37(4):768-780. doi:10.1007/s10865-013-9527-4

- Zomahoun HTV, Guénette L, Grégoire JP, et al. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing interventions on medication adherence in adults with chronic diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(2):589-602. doi:10.1093/ije/dyw273

- Kaltman S, Tankersley A. Teaching motivational interviewing to medical students: A systematic review. Acad Med. 2020;95(3):458-469. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003011

- Dunhill D, Schmidt S, Klein R. Motivational interviewing interventions in graduate medical education: a systematic review of the evidence. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(2):222-236. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-13-00124.1

- Keeley RD, Burke BL, Brody D, et al. Training to use motivational interviewing techniques for depression: a cluster randomized trial. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27(5):621-636. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2014.05.130324

- Söderlund LL, Madson MB, Rubak S, Nilsen P. A systematic review of motivational interviewing training for general health care practitioners. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84(1):16-26. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2010.06.025

- Schwalbe CS, Oh HY, Zweben A. Sustaining motivational interviewing: a meta-analysis of training studies. Addiction. 2014;109(8):1287-1294. doi:10.1111/add.12558

- Hall K, Staiger PK, Simpson A, Best D, Lubman DI. After 30 years of dissemination, have we achieved sustained practice change in motivational interviewing? Addiction. 2016;111(7):1144-1150. doi:10.1111/add.13014

- Singh Ospina N, Phillips KA, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, et al. Eliciting the patient’s agenda – Secondary analysis of recorded clinical encounters. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(1):36-40. doi:10.1007/s11606-018-4540-5

- Gollwitzer PM. Implementation intentions: strong effects of simple plans. Am Psychol. 1999;54(7):493-503. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.7.493

- Sheeran P, Webb TL, Gollwitzer PM. The interplay between goal intentions and implementation intentions. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2005;31(1):87-98. doi:10.1177/0146167204271308

- Wieber F, Thürmer JL, Gollwitzer PM. Promoting the translation of intentions into action by implementation intentions: behavioral effects and physiological correlates. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:395. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2015.00395

- Saddawi-Konefka D, Schumacher DJ, Baker KH, Charnin JE, Gollwitzer PM. Changing physician behavior with implementation intentions: closing the gap between intentions and actions. Acad Med. 2016;91(9):1211-1216. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001172

There are no comments for this article.