Introduction: Despite the public health imperative that all medical practitioners serving reproductive-aged women know the components of abortion care and attain competency in nondirective pregnancy options counseling, exposure to abortion care in US medical school education remains significantly limited.

Methods: Florida International University Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine offers an opt-in clinical exposure to abortion care during the obstetrics and gynecology clerkship. During clerkship orientation, students watched a recorded presentation reviewing components of abortion care and emphasizing that participating students may increase or decrease involvement at any time without explanation. Students opting in completed a form specifying their desired level of involvement for each component as “yes,” “no,” or “not sure.”

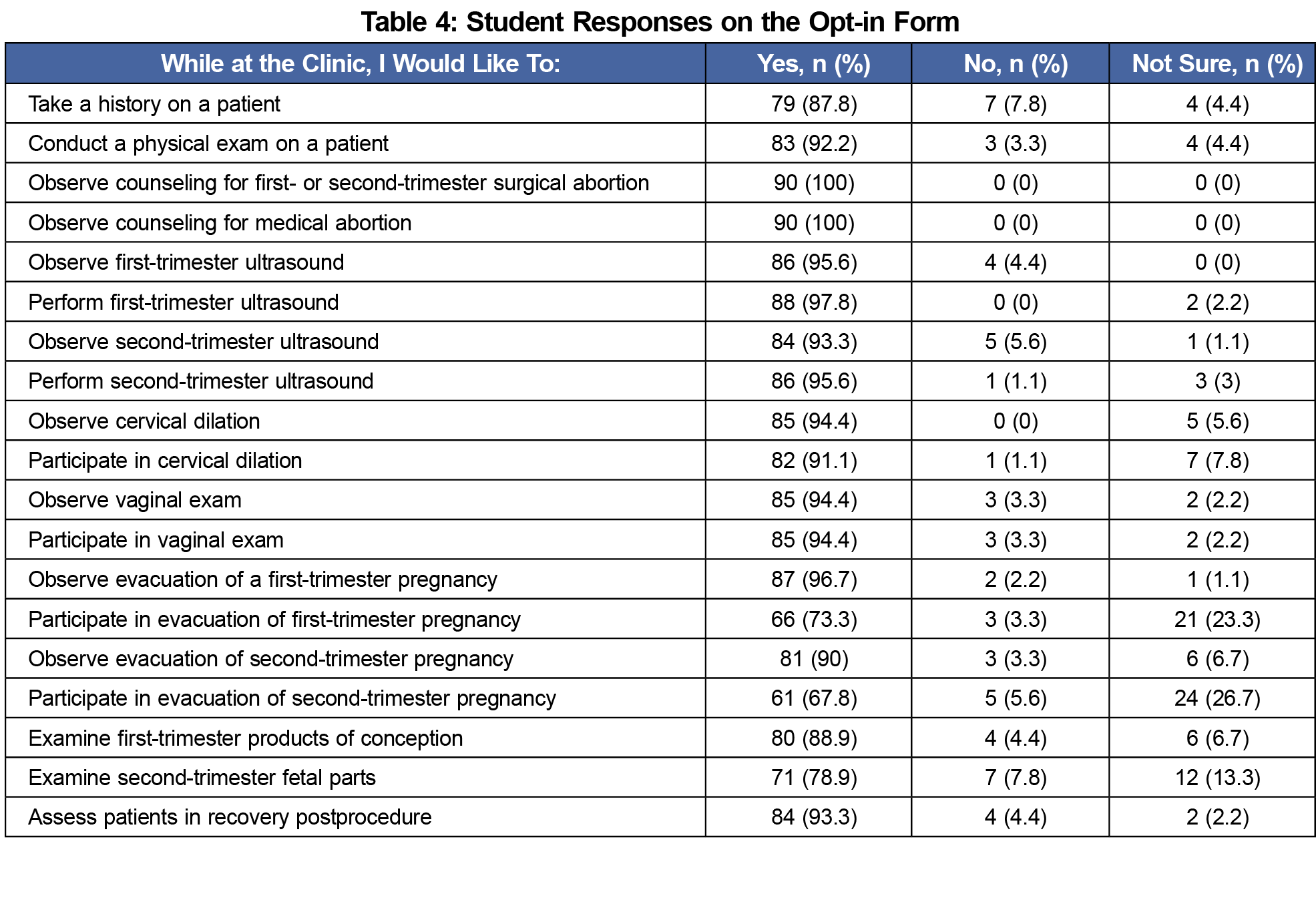

Results: Of 350 clerkship students over 23 6-week rotations, 98 (28%) chose to opt in, with opt-in form data available for 90 students. Ninety students chose to observe counseling for first- and second-trimester surgical abortion and medical abortion. Seven students used the option “no” for history taking and examine second trimester fetal parts. Twenty-four students marked “not sure” for participating in evacuation of first-trimester pregnancy.

Discussion: This educational intervention proved feasible and offers an opportunity for students to have experiential learning about abortion care in an inclusive, respectful manner. This experience may be incorporated into undergraduate and graduate medical education. Providing learners the opportunity for exposure to abortion care improves their overall medical education and will impact the care they provide as future clinicians.

All medical practitioners serving reproductive-aged women require an understanding of abortion care and nondirective pregnancy options counseling.1 Abortion education should be in all medical school curriculum.2 While the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires that obstetrics and gynecology residency programs include training or access to abortion training, the ACGME does not specifically require that family medicine programs include abortion training.3,4 Family medicine residents should be trained in well-woman care, family planning, contraception, and options counseling for unintended pregnancy.4 The American Academy of Family Physicians recommends that residents be able to provide counseling for options for unintended pregnancy.5 The Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) requires that medical school curriculum include each organ system; each phase of the human life cycle; continuity of care; and preventive, acute, chronic, rehabilitative, and end-of-life care, and does not specifically include abortion or options counseling.6

Recent data on abortion education during medical school in the United States is limited. Medical Students for Choice was founded in 1993 to train abortion providers and to further inclusion of abortion and contraception in medical school curricula.7 In 2005, 23% of third-year clerkships reported no formal curriculum, while 32% offered a lecture.8 Thirty-seven LCME-accredited schools in the United States offered fouth-year electives in 2012-2013.9 Medical educators should identify clinical learning opportunities in this area. At a faith-based school, 71% of responding fourth-year students reported inadequate abortion training and 52% desired clinical abortion training.10 Medical students want to be skilled in contraception and options counseling and are filling gaps in their education with electives.11

Educators need methods that communicate respect for learners’ moral comfort and support decisions to change boundaries in the clinical setting. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that all obstetrics and gynecology residents routinely learn about abortion and that those residents with religious or moral objections can opt out of participation.2 Of 362 fourth-year residents in US obstetrics and gynecology residency programs, 54% reported routine and elective training, 30% reported opt-in training, and 16% reported none and no elective abortion training.12 Of 94% responding Canadian program directors in obstetrics and gynecology, half utilized opt-in abortion training and half utilized opt-out training.13 The Midwest Access Project offers opt-in abortion training to students, residents, and clinicians, and found that half of participants provided some type of abortion care and almost all provided comprehensive contraception and counseling.14

Offered since early 2017, our flexible opt-in experience has offered clinical exposure to abortion care, including exposure to all aspects including options counseling, preoperative counseling and care, procedures, ultrasounds, and postoperative care. While this intervention was performed on the obstetrics and gynecology rotation, this intervention could easily be performed on the family medicine rotation or as a resident rotation. All students on the rotation received abortion care content through a reading assignment and didactic session. “Opt in” means that this experience is supplemental and elective, with students deciding whether they want to attend and what they are willing to observe and/or participate in during the 1-day experience.

The learning objective of the 1-day rotation is to observe or practice complex communication skills such as options counseling, and/or informed consent, and to observe and/or practice procedural skills related to abortion and post-op care, including uterine evacuation, imaging, and pain control.

To prevent any assumption that the decision to opt in could influence grading or management of day-to-day clinical experience on the clerkship, we decided that course leadership should not directly inform students of the opt-in experience. Rather, during each obstetrics and gynecology clerkship orientation, all students watched a recorded voice-over PowerPoint presentation detailing the logistics of the opt-in experience (site address/hours/parking), importance and components of abortion care, and student ability to increase or decrease involvement at any time during participation, without explanation. The presentation also encourages learners to ask classmates who have participated about their experience and, if interested, to email the clerkship coordinator. We revised the video after the first rotation to correct minor details and to add student comments about the experience.

Students choosing to opt in completed the opt-in form specifying their desired level of involvement for each component as “yes,” “no,” or “not sure.” Students could choose from a full spectrum of activities from observation to participation. Students brought the completed form with them to clinic where the nurse practitioner reviewed their responses, affirming their ability to expand or limit their participation at any time. This form is available on the STFM Resource Library.15 We conducted Pearson c2 analysis, t-test analysis, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) to analyze for year-to-year differences among students opting in.

At the end of every clerkship, students completed a standard evaluation online. While there were no specific questions evaluating the opt-in experience, students were able to evaluate the site and write comments in the general comment section. This study was approved by the Florida International University Institutional Review Board (protocol IRB-19-0011).

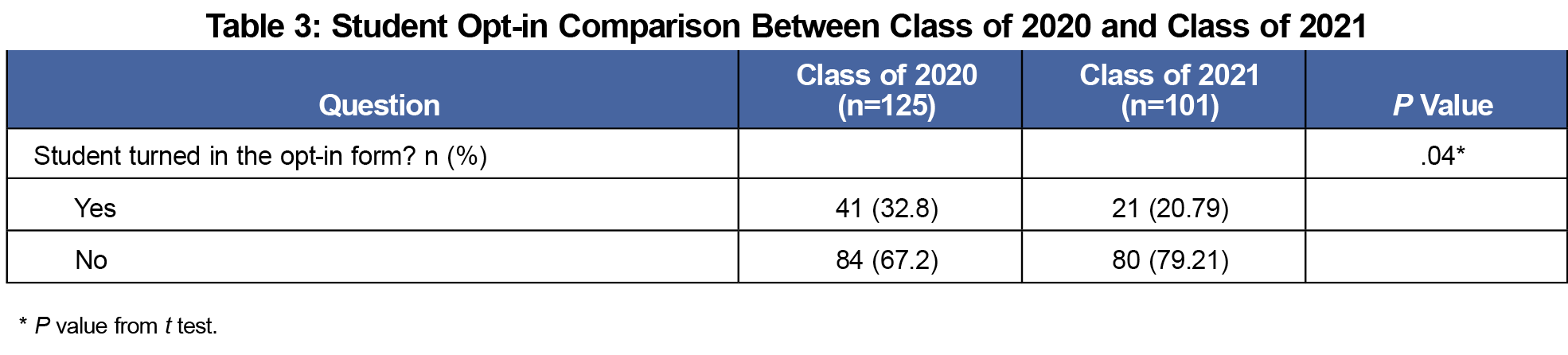

Of the 350 students who rotated on 23 6-week block rotations, 98 (28%) chose to opt in, with opt-in form data available for 90 students (Table 1). Data from the final rotation of the 2019-2020 academic year were not included as the year was shortened with student removal from the clinical setting due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Results from the c2 analysis and overall ANOVA indicated no statistically significant differences among the three cohorts (Tables 2 and 3). The 2020 cohort showed a 32.8% opt-in rate while the 2021 cohort showed a 20.79% opt-in rate. This difference resulted in statistically significant difference with the t test between the two groups (Table 3).

Analysis of the 90 opt-in forms showed 90 (100%) students chose to observe counseling for first-or second-trimester surgical abortion and observe counseling for medical abortion (Table 4). Seven (8%) students used the option “no” regarding history-taking and examining second trimester fetal parts. Twenty-four (27%) students marked “not sure” for participation in second-trimester evacuation, and 21 (23%) marked “not sure” for participation in evacuation of first-trimester pregnancy.

Student clerkship evaluation comments included:

- “You can alternate time between surgeries, ultrasounds, preparation for procedures, first-trimester suction abortion, patient education for those opting for medical (vs surgical) termination, etc.”

- “If you’re uncomfortable with anything it is completely okay to step out of the rooms at any time.”

- “You are completely welcomed to see or not see anything at any time throughout the day. They are all very open to questions.”

This opt-in experience offers an opportunity for students to have experiential learning about abortion care in an inclusive, respectful manner. This educational intervention proved to be feasible and successful, with 28% of students opting to participate. The majority of our third-year medical students who chose exposure to abortion care were open to the full range of participation. Those who did not want to fully participate expressed uncertainty rather than refusal, and all but two students chose to participate in evacuations. The variation in initial choices of procedures and segments of abortion care, and in their level of certainty, may suggest that being able to choose certain experiences could be important to their decision to participate at all and that the flexibility to change those decisions within the clinical experience could also matter to students.

Beyond their personal views, other factors may influence their choices. Unexpectedly, some students opted out of performing activities available to them in other areas of the clerkship, such as first trimester ultrasounds.

There was a decided decrease in student participation in the last class studied, with 32.8% of students from the class of 2020 opting in and 20.8% of students from the class of 2021 opting in. This may be due to students’ inability to access the opt-in experience due to the COVID-19 pandemic causing significant curriculum change in March 2020.

Gaps in medical education around abortion education and care in both undergraduate and graduate medical education persists. Regardless of the personal views of providers, it is imperative for all physicians to understand options, access, and the possible physical, psychological, and emotional outcomes of reproductive choices. We present one approach to help students consider exposure to abortion care. This opt-in approach can be used wherever this experience is available, in undergraduate and graduate medical education. Providing learners the opportunity for exposure to abortion care improves their overall medical education and will impact the care they provide as future clinicians

Our study has several limitations. Finding an appropriate site and preceptor were vital to our success. Students were able to participate certain days of the week, and the site required most students to commit significant drive time to access the site, which may have limited the number of students choosing the experience. With our focus on providing an effective learning experience, we did not evaluate why students chose to participate or not participate in this opt-in experience, nor if they changed their minds and participated to a degree that did not reflect the responses on their opt-in form. Future research regarding specific factors facilitating participation is being pursued, specifically why students chose to opt in or to not to opt in, as well as for students who chose to opt in, factors contributing to students’ decisions regarding their level of participation.

Acknowledgments

Presentations: The Use of Technology in Faculty Development for Community-Based Preceptors: A CERA Study. Society of Teachers of Family Medicine 2018 Conference on Medical Student Education. Austin, TX; February 2, 2018.

References

- APGO Women’s Healthcare Education Office. Women’s Health Care Competencies for Medical Students: Taking Steps to Include Sex and Gender Differences in the Curriculum. Crofton, MD: Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics; 2005.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee Opinion. Abortion Training and Education. Number 612; November 2014, reaffirmed 2017. Accessed October 5, 2021. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2014/11/abortion-training-and-education

- ACGME Review Committee for Obstetrics and Gynecology. Clarification on Requirements Regarding Family Planning. ACGME OB. 2021. Accessed June 23, 2021. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramResources/Clarification_Family_Planning.pdf?ver=2019-06-25-092940-700

- ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine. July 1, 2020. Accessed June 23, 2021. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/120_FamilyMedicine_2020.pdf?ver=2020-06-29-161615-367

- Recommended Curriculum Guidelines for Family Medicine Residents, Women’s Health and Gynecologic Care, AAFP Reprint No. 282. Revised August 2018. Accessed June 23, 2021. https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/medical_education_residency/program_directors/Reprint282_Women.pdf

- Functions and Structure of a Medical School. Liaison Committee on Medical Education. March 2021. Accessed June 23, 2021. https://lcme.org/publications/

- Evans ML, Backus LV. Medical students for choice: creating tomorrow’s abortion providers. Contraception. 2011;83(5):391-393. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.019

- Espey E, Ogburn T, Chavez A, Qualls C, Leyba M. Abortion education in medical schools: a national survey. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(2):640-643. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2004.09.013

- Veazey K, Nieuwoudt C, Gavito C, Tocce K. Student perceptions of reproductive health education in US medical schools: a qualitative analysis of students taking family planning electives. Med Educ Online. 2015;20(1):28973. doi:10.3402/meo.v20.28973

- Guiahi M, Maguire K, Ripp ZT, Goodman RW, Kenton K. Perceptions of family planning and abortion education at a faith-based medical school. Contraception. 2011;84(5):520-524. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.03.003

- Veazey K, Nieuwoudt C, Gavito C, Tocce K. Student perceptions of reproductive health education in US medical schools: a qualitative analysis of students taking family planning electives. Med Educ Online. 2015;20(1):28973. doi:10.3402/meo.v20.28973

- Turk JK, Landy U, Chien J, Steinauer JE. Sources of support for and resistance to abortion training in obstetrics and gynecology residency programs. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(2):156.e1-156.e6. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.04.026

- Liauw J, Dineley B, Gerster K, Hill N, Costescu D. Abortion training in Canadian obstetrics and gynecology residency programs. Contraception. 2016;94(5):478-482. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2016.07.014

- Stulberg DB, Monast K, Dahlquist IH, Palmer K. Provision of abortion and other reproductive health services among former Midwest Access Project trainees. Contraception. 2018;97(4):341-345. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.01.002

- Minor S, Martinez R, Lupi C. Abortion Opt in Form. STFM Resource Library. Posted July 30, 2021. Accessed October 5, 2021. https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/opt-in-form?CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a&tab=librarydocuments

There are no comments for this article.