Introduction: Experts suggest that leadership education should begin during medical school. However, little information exists on preferences of medical students on leadership development and particularly of those who want to work with underserved communities. This student-led study surveyed medical students on leadership development skills and perceptions on curricular needs.

Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional study using a 26-question survey with Likert scales, multiple choice, and open-ended questions. We anonymously surveyed 83 students (medical school years 1 through 4) at the Keck School of Medicine of University of Southern California and conducted a one-time focus group with six students to assess leadership aspirations and training needs. We compared student responses based their desire to serve in underserved communities in their careers.

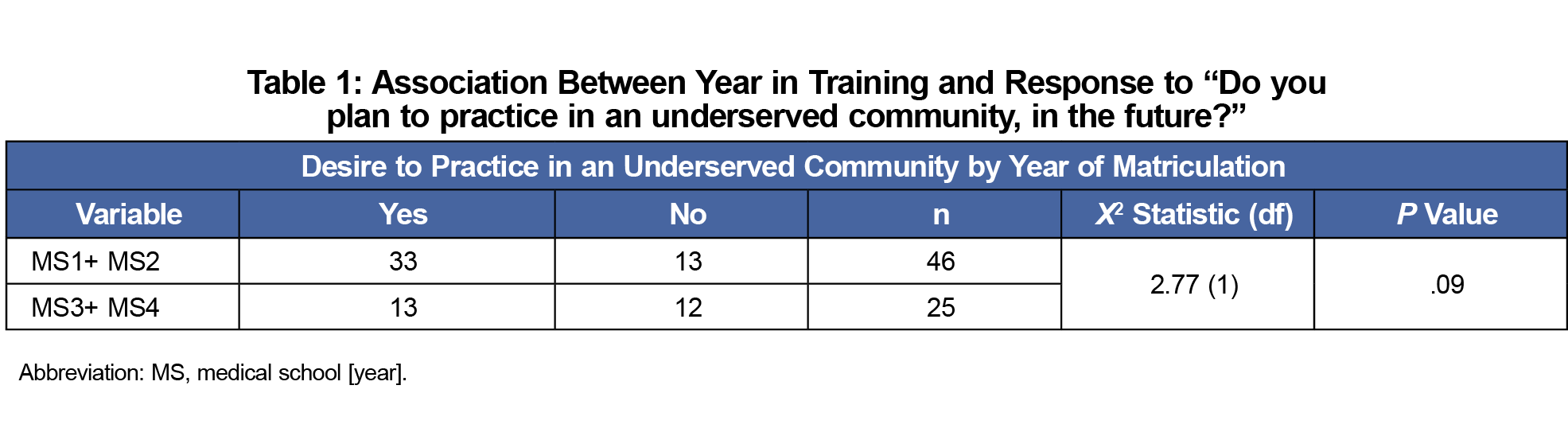

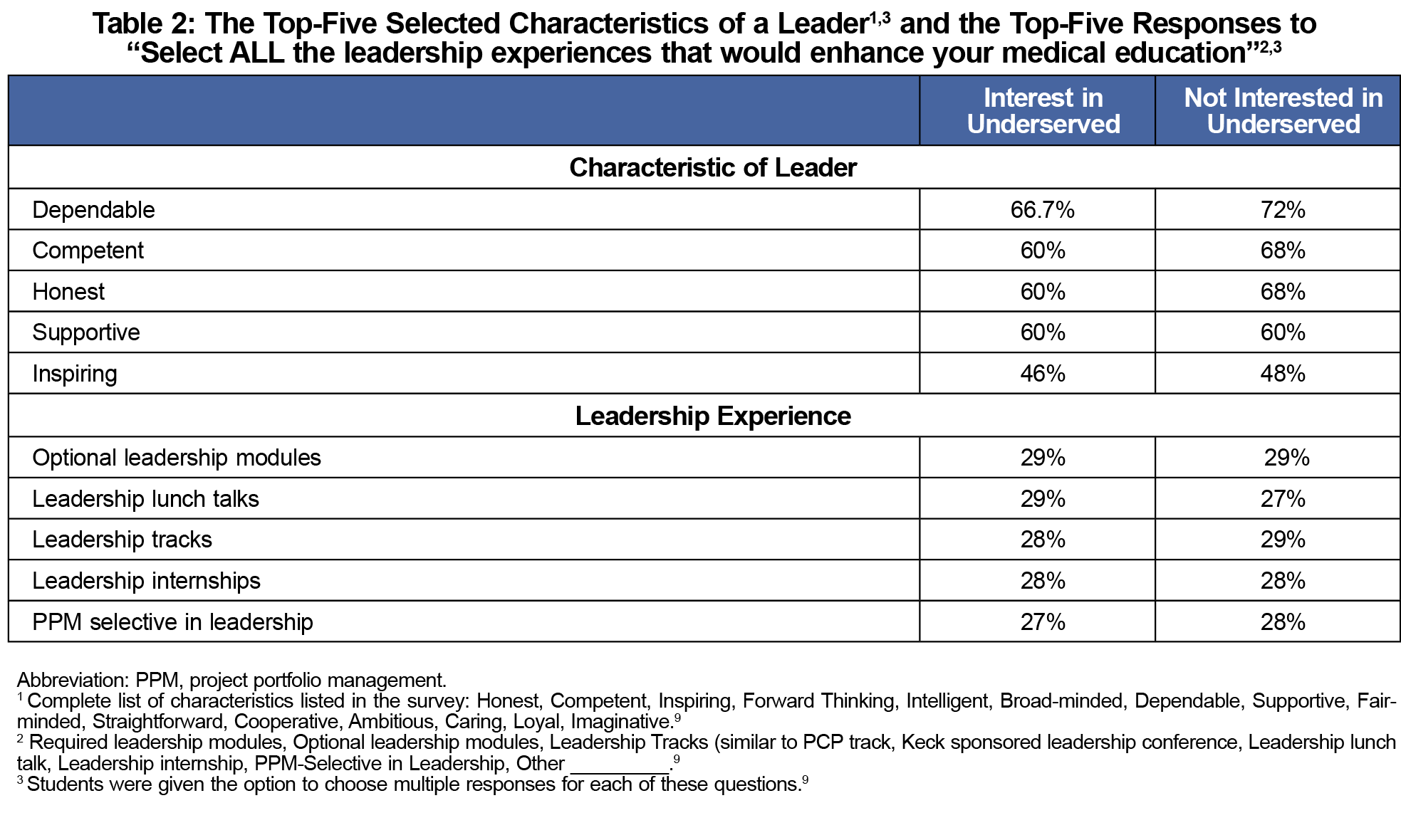

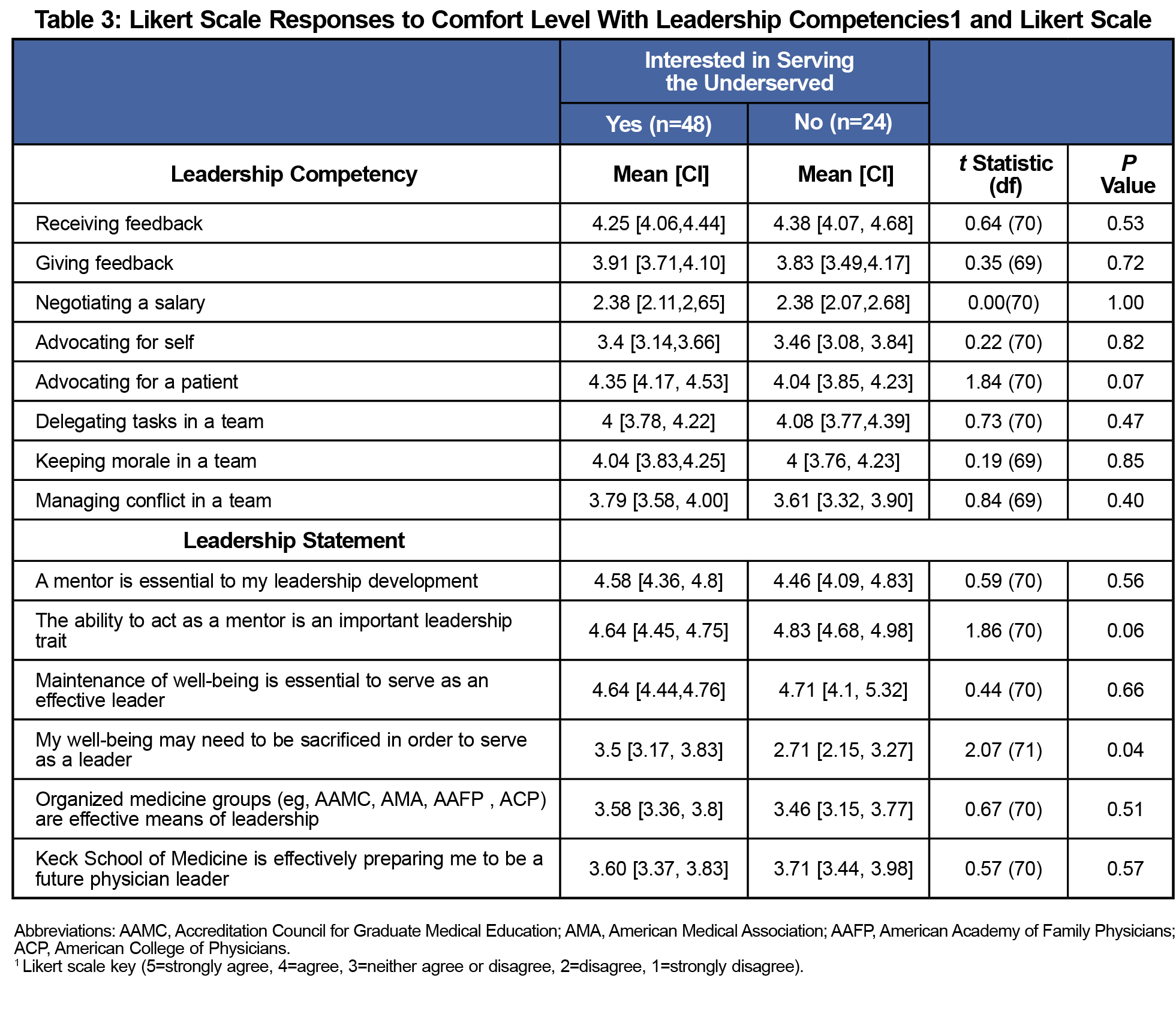

Results: Medical student desire to practice in underserved communities was greatest among respondents in their first 2 years (62% and 67%), compared to 36% and 53% for respondents in third and fourth year, respectively. Students interested in underserved communities were statistically more likely (t test 2.07, P=.04) to indicate “My well-being may need to be sacrificed in order to serve as a leader,” based on the survey. The survey showed similar top-five leader characteristics (competent, dependable, honest, inspiring, supportive) were valued among all respondents. Optional leadership modules were selected to enhance medical education by the most respondents and could potentially meet their curricular needs.

Conclusion: Our findings show that medical students welcome leadership training opportunities and prefer optional longitudinal modules. Students who plan to practice in underserved communities have similar preferences on training but may need additional support related to maintaining their well-being.

It is understood that society views physicians as healers and leaders. Carsen and Xia said, “In addition to clinical responsibilities, physicians serve as leaders and advocates at the individual, community, and societal levels.”1 Furthermore, Neely et al noted, “Experts have suggested that leadership education should begin during medical school; however, little information exists regarding the development of undergraduate medical education leadership curricula.”2

Various medical schools have developed tracks or programs that promote leadership development, specifically in underserved communities.3-5 These programs demonstrate the growing emphasis placed on leadership development in undergraduate medical education (UME). To enhance these efforts, student perspectives on leadership needs, particularly for those interested in underserved communities, should inform leadership education.

This study aimed to gain Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California (KSOM) students’ perspectives on leadership skills and curricular preferences, and attempted to understand the needs of students who desire to practice in underserved communities. We hypothesized that an interest in leadership development at the UME level exists, and that needs may differ based on desire to practice in underserved communities.

This cross-sectional study consisted of an online survey and in-person focus group. It was designed to elucidate any gaps in leadership instruction at KSOM through student input.

Participants

We recruited a convenience sample by disseminating the assessment across all class Facebook pages and listservs; and promoted it via a one-time email and Facebook reminders inviting any interested students to participate. We also invited students on leave of absence (LOA).

Online Survey

The 26-question, anonymous survey consisted of Likert-scale, multiple choice, and open-ended questions, and took 15-20 minutes to complete.9 The authors created the survey, and it was not based on validated instruments.

Focus Group

We invited participants to participate in a 1-hour focus group moderated by a coinvestigator and transcribed by the other authors, who were both second-year medical students at the time of the study, to obtain additional perspectives on leadership needs such as preparation for a career in leadership, and interest in leadership training. Participants were all medical students at the same institution as the researchers and were at various levels of their training. We obtained iLive transcription and audio recording without recording participants’ names, and transcripts were not returned to the participants. Upon completion, participants received a $10 gift card.

Data Analysis

The survey was hosted by Qualtrics. Depending on the structure of the question, we used frequencies, confidence intervals, 𝜒2 tests and t-tests to analyze the data. We analyzed participants’ responses to questions 1-8, and 249 were analyzed by calculating the frequencies. We analyzed questions 1 and 7 using a 𝜒2. We presented questions 9-16 in a Likert scale, with a numerical scale of 1 indicating extremely uncomfortable, and 5 indicating extremely comfortable. Questions 17-22 were also represented in Likert scale, with the numerical scale of 1 indicating strongly disagree and 5 indicating strongly agree. We used the mean value and standard deviation for each set of responses to calculate confidence intervals, and performed t tests to compare mean values in responses between students who indicated a desire in participating in underserved communities versus those who did not (question 7). Questions 23 and 25 were free-response questions, and we analyzed the data for these questions by grouping the responses into themes. Question 26 asked participants if they were interested in participating in a focus group.

Based on Grounded Theory of Analysis, the focus group transcription was independently coded by two raters, conflicts were resolved via discussion, all codes were categorized into themes and salient quotes were extracted. The University of Southern California Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Participant Demographics and Interest in Practicing in Underserved Communities (Questions 1 and 7)

Out of 717 KSOM students, 83 completed the survey (11.6%). Desire to practice in underserved communities was highest among respondents in their first 2 years (62% and 67%), compared to 36% and 53% for respondents in their third and fourth year, respectively (Table 1). However, 𝜒2 analysis revealed that there was no statistically significant difference in desire among the two groups.

Characteristics of a Leader (Question 3)

Participants selected competent, dependable, honest, inspiring, supportive, as the top-five characteristics of a leader from a total of 14 options.8,9 Students were asked to choose up to five characteristics. We sorted the responses based on their interest in underserved communities (Table 2).

Preferred Modalities for Leadership Education (Question 24)

Participants selected all of the leadership experiences that would enhance their education, with optional leadership modules preferred by both groups (Table 2).

Comfort Level of Leadership Competencies (Questions 9-16)

Participants recorded their comfort level with 8 author-developed leadership competencies using a Likert scale (Table 3). Among them, negotiating a salary scored the lowest (2.38) for both groups. Conversely, both scored receiving feedback and advocating for a patient highly. We analyzed the differences in responses between the two groups using independent t tests, which found that there was no statistically significant difference in the mean responses for both groups.

Participants’ Leadership Desires and Viewpoints (Questions 17-22)

Participants recorded their comfort level with 8 author-developed leadership competencies using a Likert scale (Table 3). Among them, negotiating a salary scored the lowest (2.38) for both groups. Conversely, both scored receiving feedback and advocating for a patient highly. We analyzed the differences in responses between the two groups using independent t tests, which found that there was no statistically significant difference in the mean responses for both groups.

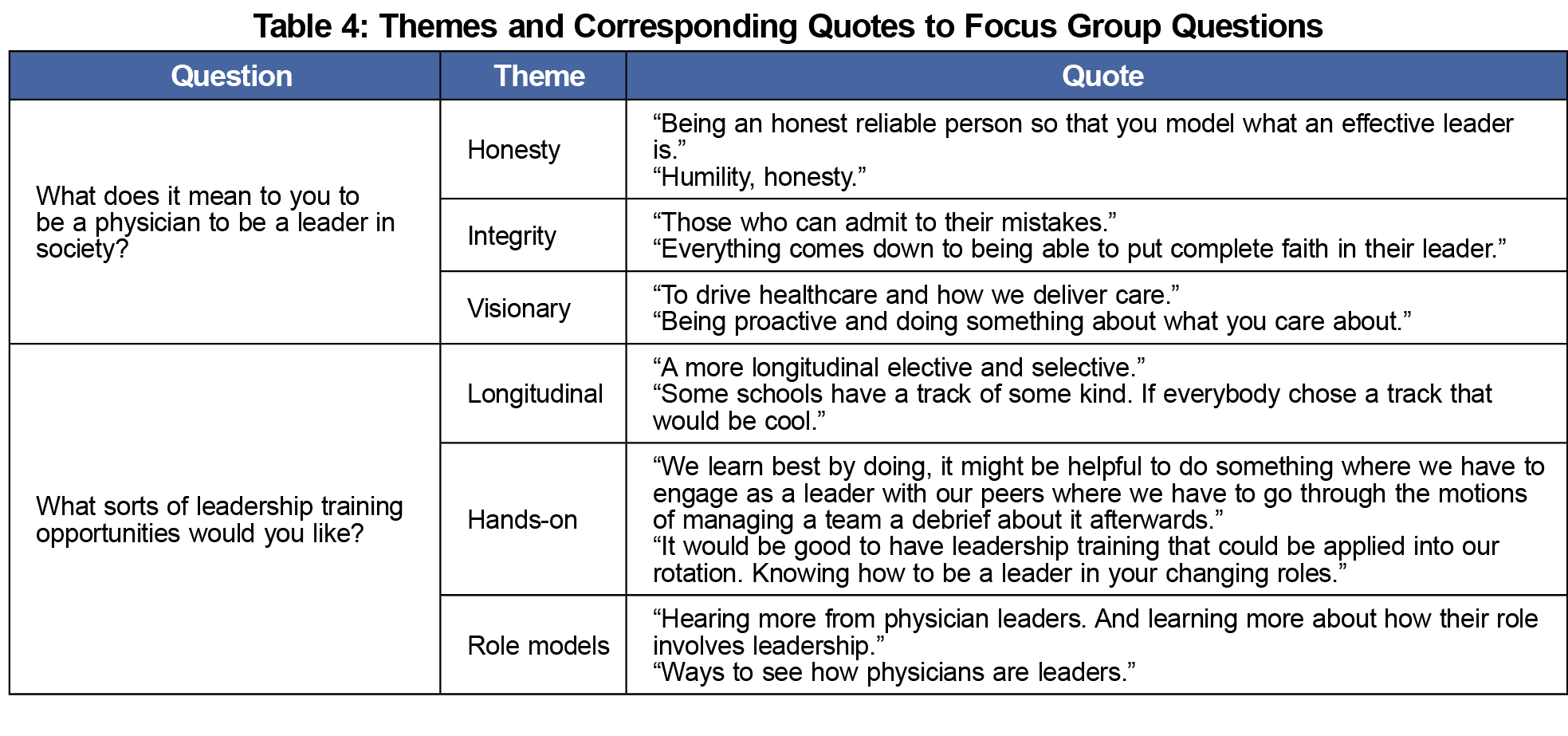

Focus Group

Six students participated in the focus group. All answered yes, when asked, “Are you considering practicing medicine in an underserved setting?” When asked, “What does it mean to you to be a physician to be a leader in society?” common themes were honesty, integrity, and visionary, and when asked “What sorts of leadership training opportunities would you like?” common themes included having longitudinal, hands-on experiences and role models (Table 4).

Our findings show that both groups of KSOM respondents welcome leadership training opportunities. Both groups selected optional leadership modules as their preferred modality, which could point towards developing self-directed teaching modules. Overall, our study did not show a significant difference in the needs of both groups.

Both groups ranked the same leadership characteristics in their top five. These characteristics can be further explored and serve as a foundation in leadership education. Further, among the surveyed leadership competencies, negotiating a salary had the lowest mean among both groups (2.38). Introducing this skill early in medical training may allow students to feel comfortable with these conversations later on, to help ensure job satisfaction and retention.

Plan to practice in underserved communities differed between respondents at the beginning of their training and respondents at the end. While the difference in responses was not statistically significant, it is still worth noting. To further assess this difference, surveying a larger sample of students may be necessary. Additionally, those who expressed interest to practice in underserved communities were more likely to agree with question 20 in the survey, which may point to needs for wellness and resilience education, while further exploring student interpretation of the question.

Methodological weaknesses include limited generalizability, since one medical student body was surveyed. However, this assessment could serve as a template for others. Also, some participants left questions unanswered leading to differing N values in the individual responses. Further, the survey wasn't validated, making it challenging to compare findings with other studies.

To address health care system challenges, UME leadership development is essential, and our findings show that KSOM students agree. Our next phase includes sharing our findings with the KSOM Curriculum Committee. We will also explore research opportunities on fostering wellness and resilience for those planning on practicing in underserved communities.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge their mentors, Dr Paul DeChant, Dr Ron Ben Ari, Association Dean for Curriculum at the Keck School of Medicine of USC (KSOM), and Dr Annie Nguyen, Assistant Professor of Family Medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. They acknowledge the KSOM Office of Curriculum, Office of Career Advising, and Office of Student Research, as well as the American Academy of Family Physicians, Emerging Leader Institute, the KSOM Research Fellowship Program, and the KSOM medical students for all of their support.

Financial support: The American Academy of Family Physicians Foundation provided financial support for this project through the Emerging Leader Institute.

Presentations: This study was presented in the following venues:

- 2018 Keck School of Medicine of USC Medical Student Research Forum, April 2018, Los Angeles, CA.

- American Academy of Family Physicians, 2018 National Conference, Emerging Leader Institute Award Winner Poster Session, July 2018, Kansas City, MO.

- 2020 Society for Teachers of Family Medicine Conference on Medical Student Education, February 2020, Portland, OR.

References

- Carsen S, Xia C. The physician as leader. McGill J Med. 2006;9(1):1-2.

- Neeley SM, Clyne B, Resnick-Ault D. The state of leadership education in US medical schools: results of a national survey. Med Educ Online. 2017;22(1):1301697. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2017.1301697

- Dobie SA, Huffine C. Training medical students in community leadership. Acad Med. 1994;69(5):428. doi:10.1097/00001888-199405000-00051

- Girotti JA, Loy GL, Michel JL, Henderson VA. The urban medicine program: developing physician-leaders to serve underserved urban communities. Acad Med. 2015;90(12):1658-1666. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000970

- Haq C, Grosch M, Carufel-Wert D. Leadership Opportunities with Communities, the Medically Underserved, and Special Populations (LOCUS). Acad Med. 2002;77(7):740. doi:10.1097/00001888-200207000-00026.

- Hartzell JD, Yu CE, Cohee BM, Nelson MR, Wilson RL. Moving beyond accidental leadership: a graduate medical education leadership curriculum needs assessment. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1815-e1822. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00365

- Sheline B, Tran AN, Jackson J, Peyser B, Rogers S, Engle D. The Primary Care Leadership Track at the Duke University School of Medicine: creating change agents to improve population health. Acad Med. 2014;89(10):1370-1374. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000305

- Kouzes JM, Posner BZ. The Leadership Challenge. New York: Wiley; 2017.

- Mota AB, Madrigal A, Zia S, Robinson J. Leadership Needs Assessment. STFM Resource Library. Posted September 7, 2021. Accessed October 4, 2021. https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/leadership-needs-assessment?CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a&tab=librarydocuments

There are no comments for this article.