Introduction: Near-peer teaching offered by residents is common in a medical students’ educational career, so preparation of residents for their role as teachers is essential. Understanding resident perspectives on interactions with medical students may provide insight into this near-peer relationship and allow stakeholders to emphasize concepts that add value to this relationship when preparing residents to teach. This study presents the results from an inquiry focusing on a cohort of family medicine residents’ experiences with medical students in their role as teachers.

Methods: Family medicine residents at a Southeastern US academic medical center participated in one of three focus groups to assess resident perceptions of their role in teaching students and approaches employed. We coded focus group transcripts for themes.

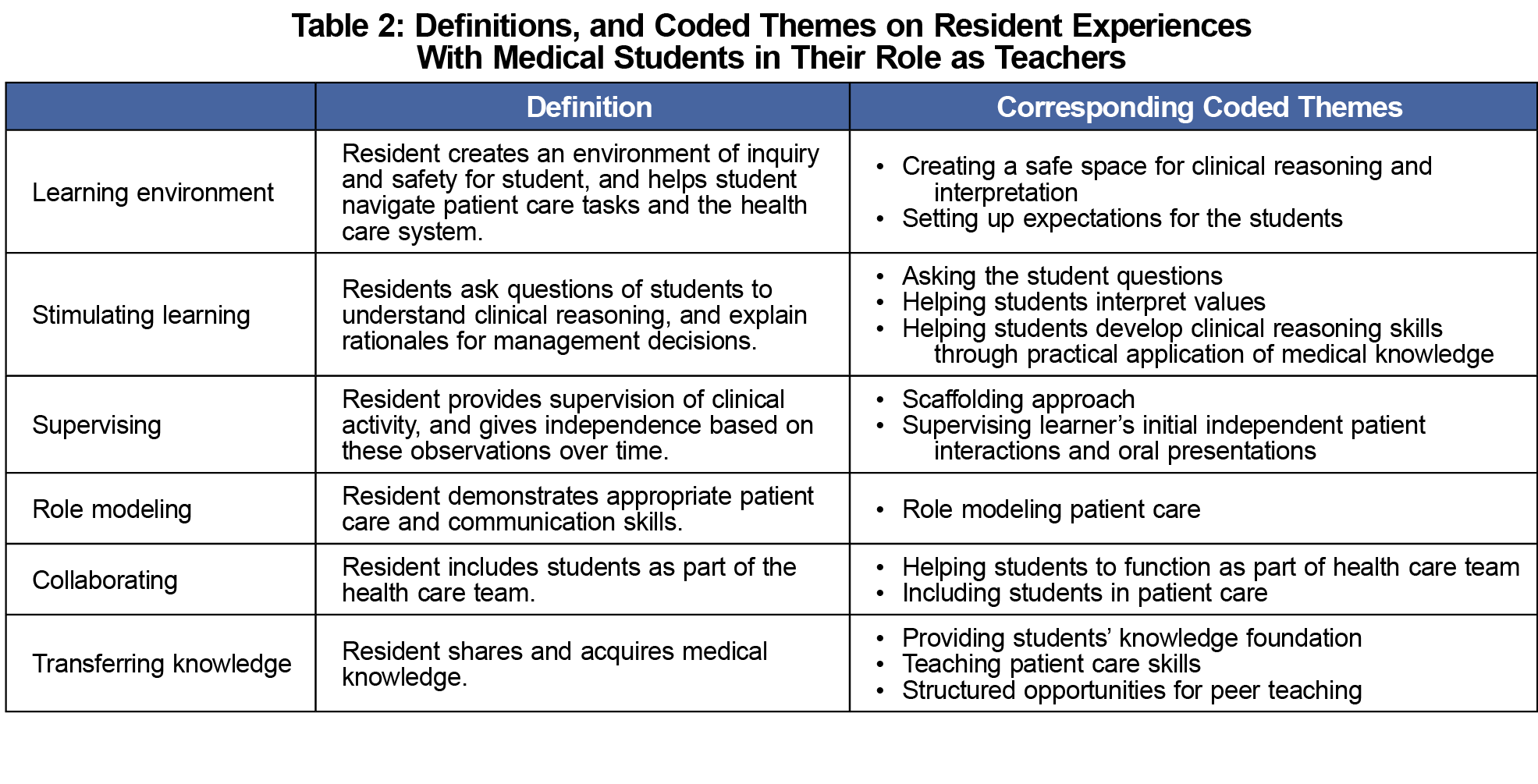

Results: Themes identified from questions on residents’ perceptions of teaching role and employed teaching approaches focused on teaching interactions and methods. Six categories of major themes were derived from this qualitative analysis: (1) the learning environment, (2) stimulating learning, (3) supervising, (4) role modeling, (5) collaborating, and (6) transferring knowledge. Trends within these categories include creating a safe environment for clinical reasoning and inquiry, setting expectations, developing clinical reasoning skills through practical application of knowledge, providing appropriate student supervision and autonomy, and including students as part of the team.

Conclusions: Residents adopted a variety of teaching approaches that assist medical students in their transition into and ability to function within a clinical environment. Findings from this study have implications for program directors and educators when preparing residents as teachers.

Resident teachers contribute a substantial amount to the educational experience for medical students. Multiple stakeholders, including residency programs,1-3 the Liaison Committee on Medical Education,4 and the Accreditation Counsel for Graduate Medical Education,3 have increasingly emphasized the preparation of residents to teach.1,2,5 Although there are core pedagogical concepts that should be incorporated into curricula to prepare residents teachers,3 these programs may require different foci than programs designed for faculty.6

Qualitative studies on student perspectives of quality resident teachers indicate creating a safe learning environment, team inclusivity, coaching, and feedback are qualities valued by medical students in resident teachers.7 Residents recognize their role as teachers and need for preparation to teach,8-11 however there is little in the literature about residents’ perspectives on their experiences teaching students.

As near-peer learners, the interactions between medical students and residents differ from those between medical students and faculty. Near-peer teaching offers multiple benefits,5,12,13 including cognitive congruence, and the ability to foster a safe learning environment, because teachers better understand learner challenges, and learners feel comfortable with sharing knowledge deficits.12

Understanding residents’ current perspectives about teaching medical students can provide insight into the near-peer relationship between residents and students and allow stakeholders to tailor training programs by emphasizing concepts that add value to this relationship. This study presents the results from an inquiry focusing on exploring a cohort of family medicine residents’ experiences with medical students in their role as teachers.

The Augusta University Institutional Review Board approved the study. We developed this phenomenology study17 using focus groups in consultation with faculty appointed to Augusta University’s Educational Innovation Institute with expertise in qualitative research. We utilized focus groups to allow the use open-ended questions to individual and shared perspectives on resident experiences.

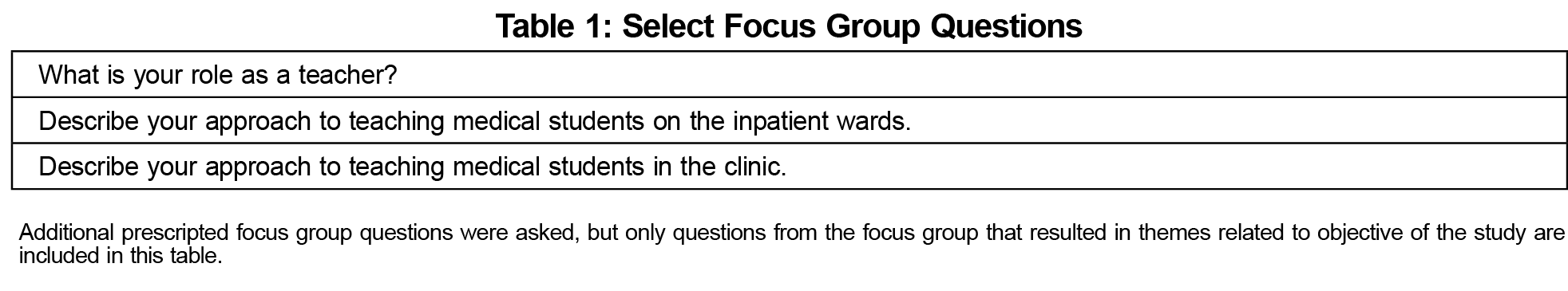

The predetermined set of questions with associated themes relevant to the objective of this study are included in Table 1. A practice focus group session ensured question clarity.

We invited all residents (N=31) from a family medicine residency program affiliated with a Southeastern US medical school to participate. The principle investigator (PI) introduced the study to the residents face to face during protected educational time. This convenience sampling of invited participants attended one of three focus group sessions offered during nonclinical time in the regular workday and voluntarily consented to participate. The fourth author (D.S.) was the focus group facilitator, and although known to the participants, she had no role in resident evaluation in her role as the departmental medical student program manager.

The audio recorded focus group sessions were held privately at the residency site with only the participants and facilitator over approximately 1 hour. The PI transcribed the audio, which was cross checked by the facilitator. We destroyed audio files to protect confidentiality.

Six study team members individually coded the deidentified transcripts from all three sessions for themes. Prior to group coding through an iterative process, the study team agreed on criteria to determine final themes: (1) multiple reviewers must agree, (2) theme could not be better accounted for by another theme, and (3) theme had supporting quotes from more than one resident. We held team meetings if at least three members of group were present. Second-cycle coding was done by PI to summarize study team’s derived themes. The study team reviewed and voted, all in the affirmative, on the second-cycle coding of final themes, definitions, (Table 2) and supporting quotes identified by resident postgraduate (PG) level.

We shared derived themes with resident participants. Although response rate low, they agreed on content. We invited two additional faculty who did not participate in the initial coding process to peer review finalized themes, definitions, and supporting quotes, and they agreed on the relationship between themes and supporting quotes.

Eighteen residents (six PGY1, nine PGY2, and three PGY3) participated in the study. Emerging themes of residents’ experience with students in their role as teachers centered on teaching methods. These themes and their definitions (Table 2) fell into six categories: (1) the learning environment, (2) stimulating learning, (3) role modeling, (4) collaborating, (5) supervising, and (6) transferring knowledge (Table 2). Table 3 presents supporting quotes for themes.

Residents identified their role as teachers in the setting of their interactions and employed teaching approaches as opposed to internal motivations, or their contribution to undergraduate medical education. Residents perceived that experiences teaching medical students focus on the medical students’ transition into and ability to function within a clinical environment. Teaching medical knowledge was a minor part of their teaching methods.

Emerging themes that support residents’ perceived experiences about medical student transition into the clinical environment are giving students a safe place to reason away from the attending physician, providing expectations of what to do so students can participate in clinical care, and including students as part of the health care team. Emerging themes that support residents’ perceived experiences regarding medical students functioning in the clinical environment include modeling patient care and assisting students in their development of clinical reasoning and application. They supervise students, but give students autonomy to practice patient care skills.

These emerging themes add to the limited literature on residents’ perception of their experiences with students in their role as teachers. The similarities between the emerging themes and some of the behaviors students value in resident teachers7 further support existing studies on resident teaching behaviors valued by medical students. A potential broad application of these findings is to inform relevant stakeholders about concepts to emphasize in preparing residents to teach students so residents are given tools to effectively leverage existing interactions with students in the clinical environment.

The limitations of this study are that findings reflect the perspectives of a resident cohort at a single institution, and they were primarily PGY-1 and PGY-2 residents.

Future directions include a follow-up study on resident perspectives on their internal motivation for teaching, barriers and challenges to teaching, and how resident and student interactions differ based on level of training and trend over time in individual residents as they progress.

Acknowledgments

Presentations: This study was presented at the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Medical Student Education Conference, January 30, 2020 through February 2, 2020, in Portland, Oregon.

References

- Al Achkar M, Davies MK, Busha ME, Oh RC. Resident-as-teacher in family medicine: a CERA survey. Fam Med. 2015;47(6):452-458.

- Al Achkar M, Hanauer M, Morrison EH, Davies MK, Oh RC. Changing trends in residents-as-teachers across graduate medical education. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2017;8:299-306. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S127007

- McKeon BA, Ricciotti HA, Sandora TJ, et al. A Consensus Guideline to Support Resident-as-Teacher Programs and Enhance the Culture of Teaching and Learning. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(3):313-318. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-18-00612.1

- Functions and Structure of a Medical School: Standards of Accredidation of Medical Education Programs Leading to the MD Degree (2021-22). Liaison Committee for Graduate Medical Education. Published March 2019. Accessed October 14, 2021. https://medicine.mercer.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2020/01/2020-21_Functions-and-Structure_2019-10-04-1-1.pdf

- Ramani S, Mann K, Taylor D, Thampy H. Residents as teachers: Near peer learning in clinical work settings: AMEE Guide No. 106. Med Teach. 2016;38(7):642-655. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2016.1147540

- Karani R, Fromme HB, Cayea D, Muller D, Schwartz A, Harris IB. How medical students learn from residents in the workplace: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):490-496. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000141

- Montacute T, Chan Teng V, Chen Yu G, Schillinger E, Lin S. Qualities of resident teachers valued by medical students. Fam Med. 2016;48(5):381-384.

- Ng VK, Burke CA, Narula A. Residents as teachers: survey of Canadian family medicine residents. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59(9):e421-e427.

- Brown RS. House staff attitudes toward teaching. J Med Educ. 1970;45(3):156-159. doi:10.1097/00001888-197003000-00005

- Apter A, Metzger R, Glassroth J. Residents’ perceptions of their role as teachers. J Med Educ. 1988;63(12):900-905. doi:10.1097/00001888-198812000-00003

- Busari JO, Prince KJ, Scherpbier AJ, Van Der Vleuten CP, Essed GG. How residents perceive their teaching role in the clinical setting: a qualitative study. Med Teach. 2002;24(1):57-61. doi:10.1080/00034980120103496

- Ten Cate O, Durning S. Peer teaching in medical education: twelve reasons to move from theory to practice. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):591-599. doi:10.1080/01421590701606799

- Ten Cate O, Durning S. Dimensions and psychology of peer teaching in medical education. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):546-552. doi:10.1080/01421590701583816

- Ricciotti HA, Freret TS, Aluko A, McKeon BA, Haviland MJ, Newman LR. Effects of a short video-based resident-as-teacher training toolkit on resident teaching. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(suppl 1):36S-41S. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002203

- Post RE, Quattlebaum RG, Benich JJ III. Residents-as-teachers curricula: a critical review. Acad Med. 2009;84(3):374-380. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181971ffe

- Bree KK, Whicker SA, Fromme HB, Paik S, Greenberg L. Residents-as-teachers publications: what can programs learn from the literature when starting a new or refining an established curriculum? J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(2):237-248. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-13-00308.1

- Creshwell JWaP. C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2017:488.

There are no comments for this article.