Background and Objectives: Medical schools must integrate educational curricula that teach how to apply quality improvement principles to improve care for vulnerable populations. In this report, we describe the development, implementation, and evaluation of a combined quality improvement (QI) and health disparities curriculum for third-year family medicine clerkship students.

Methods: After conducting an educational needs assessment, we developed a health disparities curriculum focused on QI principles for the family medicine clerkship. From November 2019 through August 2021, third-year medical students (N=395) completed the curriculum. The curriculum was delivered in an asynchronous online format, followed by a small group collaboration project to design and present a QI intervention through process mapping. Students also completed an individual reflection assignment that focused on care for vulnerable populations. Pre- and postassessment questions were administered on Qualtrics, after review by the clerkship director, research faculty and staff, and content experts for content and item validity. We analyzed quantitative data using SPSS version 27 software and used paired t tests for pre/post comparisons.

Results: In total, 392 students completed the preassessment survey, 395 students completed the postassessment surveys, and 341 had matching study identifiers. Pre-to-post assessment survey evaluations showed statistically significant changes for nine out of nine QI knowledge questions (P<.001), knowledge regarding a community health needs assessment (P<.001), and knowledge about caring for vulnerable populations (homeless, veterans, immigrants/refugees; P<.001).

Conclusions: Preliminary evaluation of a combined QI and health disparities curriculum shows improvement in students’ self-reported knowledge of use of a community health needs assessment, QI principles, and care for vulnerable populations.

Despite improvements in population health efforts, health disparities persist.1 Medical education must teach students how to recognize and address health disparities to work toward health equity. One way to achieve this is to train students to apply quality improvement (QI) principles to the care of vulnerable populations.

Health equity curricula should be integrated with clinical context.2 The report Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality identified the application of QI methodology to patient care as a required competency,3 while the Unequal Treatment report highlighted nationwide health disparities.4 The National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report1 reinforced the importance of combining QI with disparities reduction efforts.

In a 2020 survey of 41 US medical schools, 100% of surveyed schools included curriculum on health disparities and 83% of schools taught QI; however, only 16 of the 41 schools required students to complete a QI project.5 We developed a curriculum for third-year family medicine clerkship students involving how to (1) navigate a community health needs assessment, (2) recognize and identify health disparities, and (3) apply QI principles to design an intervention that would benefit vulnerable populations. This paper will describe the development, implementation, and evaluation of this curriculum.

Curriculum Design and Implementation

Previously, students on the family medicine clerkship were introduced to a QI curriculum.6 To assess students’ knowledge of community-based medicine, we designed a needs assessment described in a previous study.7 We used this information to develop a health disparities curriculum with the following asynchronous online lessons: introduction to a community health needs assessment; and care for homeless, veteran, immigrant/refugee, and sexual and gender minority individuals. The community health needs assessment (CHNA) lesson contained information on evaluation of data sources, the process of how a CHNA is created, identification of priority needs, demographics, and action planning. The lessons on care for vulnerable populations included sections on demographics, historical context, health disparities, improving clinical care, and community resources. Students were asked to design a QI intervention to improve a health care process and to complete a reflection assignment that focused on improving care for a vulnerable population. Table 1 outlines the curriculum. From November 2019 through August 2021, third-year medical students (N=395) completed the curriculum during their 6-week family medicine clerkship.

Data Collection and Analysis

Pre- and postassessment questions with demographics were developed and reviewed by the clerkship director, research faculty, and staff, to ensure alignment with goals and objectives. Content experts also reviewed the questions to ensure validity. The questions asked about students’ self-assessed knowledge of QI principles, how to use a CNHA, and how to care for vulnerable populations. Both surveys were administered on Qualtrics, with pre- and post matching with response scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Students were not required to answer all questions, and surveys were anonymous. We analyzed quantitative data using SPSS version 27 software and used paired t tests for pre/post comparisons. We used linear regression to assess whether any demographic (age, gender) or background variables (being a first generation student vs not, raised in an urban environment vs not, or intention to participate in a loan forgiveness program vs not) were associated with changes in students’ knowledge. Thomas Jefferson University’s Institutional Review Board approved this study.

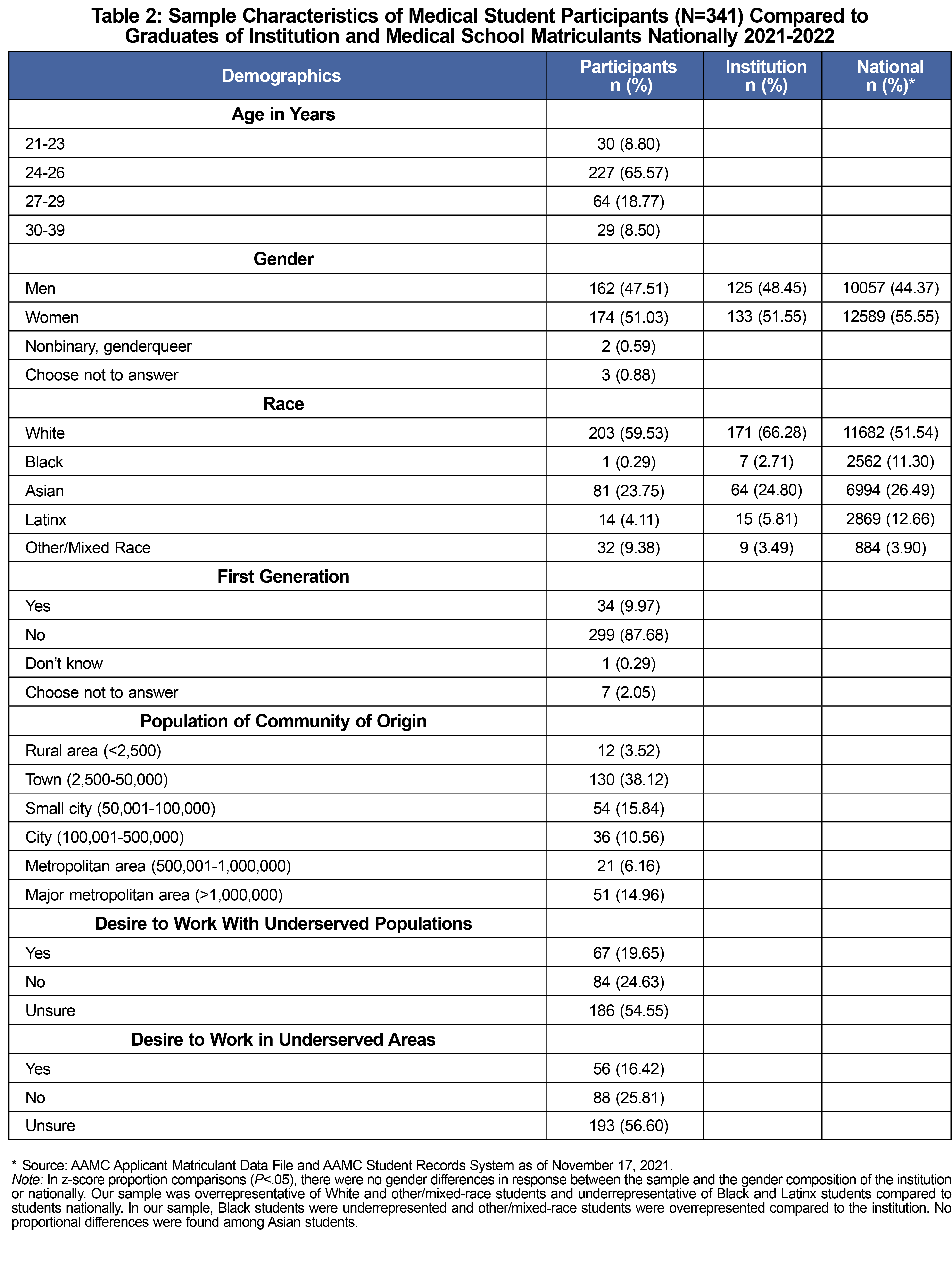

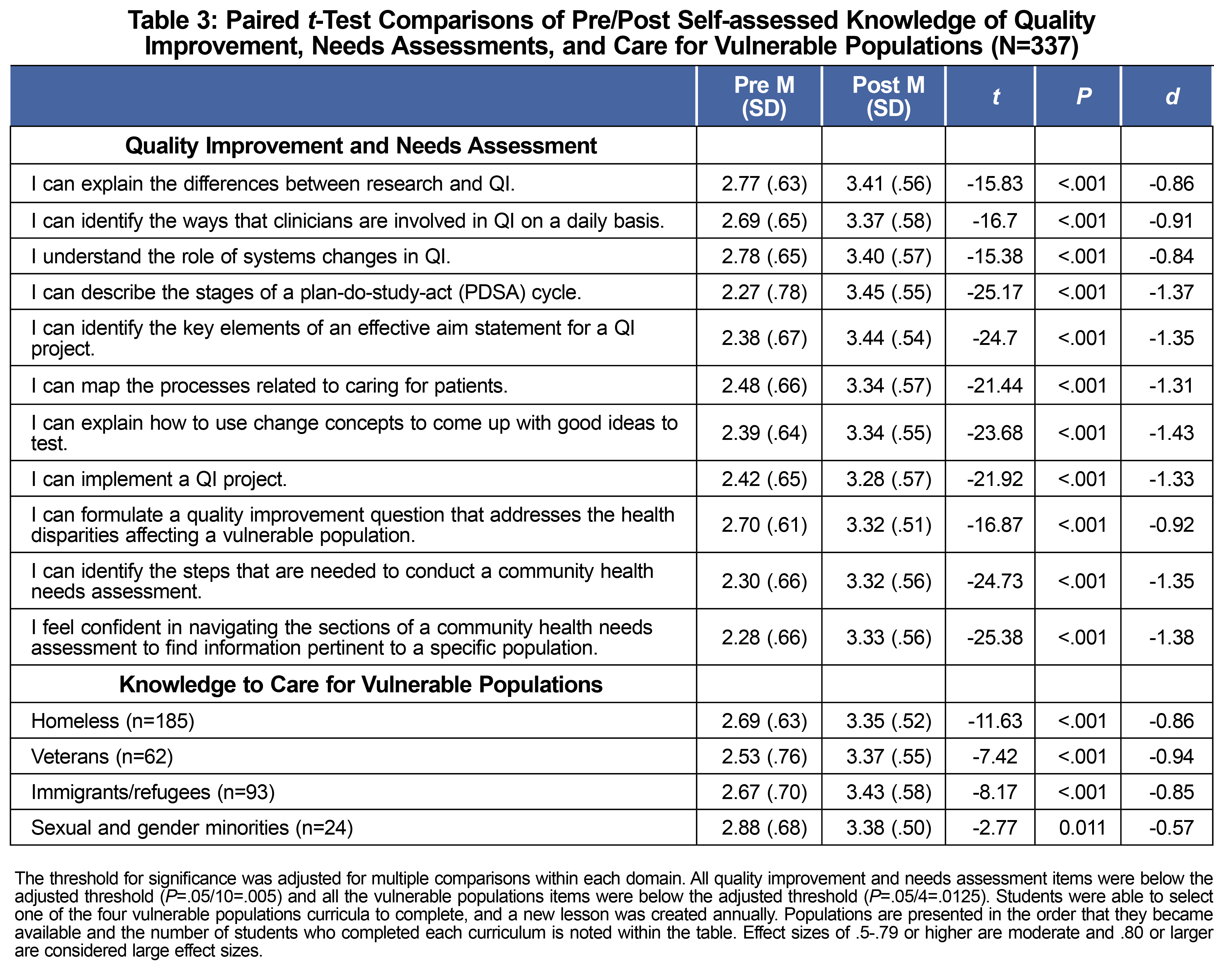

In total, 392 students completed the preassessment survey, 395 students completed the postassessment surveys, and 341 had matching study identifiers (Table 2). There were no demographic differences between those who completed both surveys or only one survey, according to 𝛘2 comparisons. Participants were primarily White (59.53%), female (51.03%), and under the age of 26 years (75.37%). Pre- to postassessment survey evaluations showed statistically significant changes for nine out of nine QI knowledge questions, including formulation of a QI question to address health disparities for a vulnerable population (P<.001), knowledge regarding a community health needs assessment (P<.001), and knowledge to care for vulnerable populations (homeless, veterans, immigrants/refugees; P<.001). Care for individuals who are sexual and gender minorities was not significant, due to the lower number of students (N=24) who had taken that lesson thus far (Table 3). The effect sizes of their self-assessed increased knowledge ranged from moderate (d=0.57) to very large (d=1.43). We used additional regression analyses to examine the factors of age, gender, being a first generation student, community size, or participation in a loan forgiveness program; none of these were significantly related to the knowledge change scores.

Process Maps

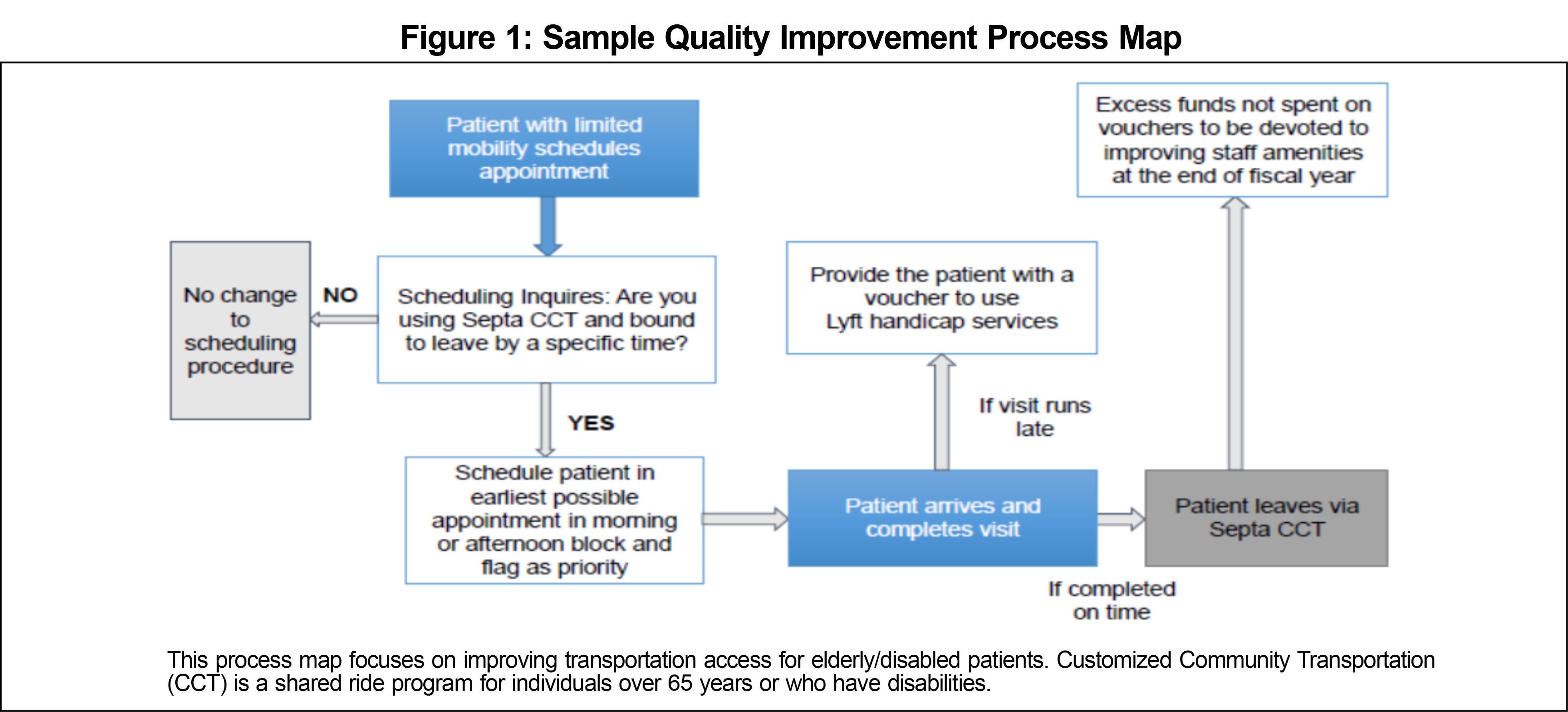

Figure 1 shows a sample process map created by a student group that focuses on improving transportation access for elderly/disabled patients. During the group presentations of their QI projects, students were asked to consider aspects such as cost, feasibility, prioritization, and stakeholder engagement. Particularly, students were challenged to think about how these interventions could be implemented, with a focus on the importance of a multidisciplinary care team. Other examples of student QI interventions included improving behavioral health linkage for individuals with mental illness, connecting diabetic patients to a registered dietician, improving interpreter services to ensure continuity during a visit, and connecting patients with a chronic disability with food delivery services.

Similar to community medicine curricula after which students report an improvement in perceived knowledge about health disparities,8-10 our students also reported a significant increase in their knowledge on use of a community health needs assessment, QI principles, and care for vulnerable populations. Importantly, after completion of this curriculum, they reported having the knowledge to create a QI question that addresses health disparities in a vulnerable population. A prior review found that approximately one-third of published QI interventions targeted improving care for vulnerable populations.11

During the COVID-19 pandemic, students reflected that they felt empowered to be advocates for vulnerable populations and to address health inequities, but they wanted to learn action-oriented tools and strategies as a next step.12 We asked our students to synthesize the information they learned in this curriculum to design a QI intervention and reflect on whether this intervention would need to change based on the vulnerable populations they chose to learn more about. Taking a step further, students had to consider barriers to care for these patients, and how they might create solutions to accommodate patients’ needs. A future goal is for our fourth-year students in the family medicine track to have the opportunity to implement their QI project in their final year. Regarding the design, implementation, and evaluation of their QI projects, students could be assessed on Entrustable Professional Activity 13: Identify System Failures and Contribute to a Culture of Improvement13; and/or the family medicine milestones of Systems-Based Practice 1: Patient Safety and Quality Improvement; Systems-Based Practice 3: Physician Role in Health Care Systems; or Systems-Based Practice 4: Advocacy.14

Due to the 6-week time frame of our clerkship, we only asked students to propose a QI question, but not implement it. Therefore, our pre- and postcurricular surveys have a major limitation in only assessing students’ self-report of knowledge, which is affected by response bias and assesses the lowest level on Kirkpatrick’s level of learning evaluation.15 A future goal would be for students to implement their intervention, so that we could objectively assess skill acquisition or competency attainment. Other limitations include our use of a single-institution sample that was overrepresentative of White and Other/Mixed-race students, and underrepresentative of Black and Latinx students compared to students nationally (Table 2).

Overall, this curriculum is an important first step in teaching medical students to recognize disparities, to design a quality improvement intervention with a focus on equity, and how to adjust an intervention to ensure vulnerable populations can benefit. While the focus of our program was on medical education, this curriculum could be adapted for other health professional students, residents, or faculty/community preceptors.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support and Disclaimer: This work was funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of a Primary Care Medicine and Dentistry Clinician Educator Career Development Awards Program (grant number K02HP30821). The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS, or the US Government.

References

- National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2019. Accessed September 29, 2022. https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr19/index.html

- Landry AM. Integrating health equity content into health professions education. AMA J Ethics. 2021 Mar 1;23(3):E229-234.

- Greiner AC, Knebel E, eds. Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Health Professions Education Summit.National Academies Press; 2003.

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds; Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care.National Academies Press; 2003.

- Morse R, Smith A, Fitzgerald-Wolff S, Stoltzfus K. Population Health in the Medical School Curriculum: a Look Across the Country. Med Sci Educ. 2020;30(4):1487-1493. doi:10.1007/s40670-020-01083-z

- Mills G, Kelly S, Crittendon DR, Cunningham A, Arenson C. Evaluation of a quality improvement experience for family medicine clerkship students. Fam Med. 2021;53(10):882-885. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.702090

- Smith RS, Silverio A, Casola AR, Kelly EL, de la Cruz MS. Third-year medical students’ self-perceived knowledge about health disparities and community medicine. PRiMER Peer-Rev Rep Med Educ Res. 2021;5:9. doi:10.22454/PRiMER.2021.235605

- Awosogba T, Betancourt JR, Conyers FG, et al. Prioritizing health disparities in medical education to improve care. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1287(1):17-30. doi:10.1111/nyas.12117

- Denizard-Thompson N, Palakshappa D, Vallevand A, et al. Association of a health equity curriculum with medical students’ knowledge of social determinants of health and confidence in working with underserved populations. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e210297. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0297

- Bernstein R, Ruffalo L, Bower D. A multielement community medicine curriculum for the family medicine clerkship. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10417. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10417

- Rolnitsky A, Kirtsman M, Goldberg HR, Dunn M, Bell CM. The representation of vulnerable populations in quality improvement studies. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30(4):244-249. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzy016

- Casola AR, Kelly EL, Smith K, Kelly S, de la Cruz M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical students’ perceptions of healthcare for vulnerable populations. Fam Med. in press.

- Obeso V, Brown D, Aiyer M, eds. Toolkits for the 13 Core Entrustable Professional Activities for Entering Residency. Association of American Medical Colleges; 2017.

- Hamstra SJ, Kenji Y, Shah H, et al. ACGME Milestones National Report, 2019. Accessed April 19, 2021. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/2019MilestonesNationalReportFinal.pdf?ver=2019-09-30-110837-587

- Kirkpatrick DL. Evaluating Training Programs: The Four Levels.3rd ed. Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2009.

- Southeastern Pennsylvania Community Health Needs Assessment. Updated 2019. Accessed June 2, 2020. https://www.jeffersonhealth.org/content/dam/health2021/documents/informational/community-health-needs-assessment-2019.pdf

- Community Commons. Accessed May 11, 2020. https://www.communitycommons.org

There are no comments for this article.