Introduction: Residency training is associated with stress and burnout that can contribute to poor mental health. However, residents are less likely to utilize mental health services due to perceived barriers such as lack of time and concerns about confidentiality, among others.1 There is a need to promote help-seeking behavior and improve access to mental health services during residency training.

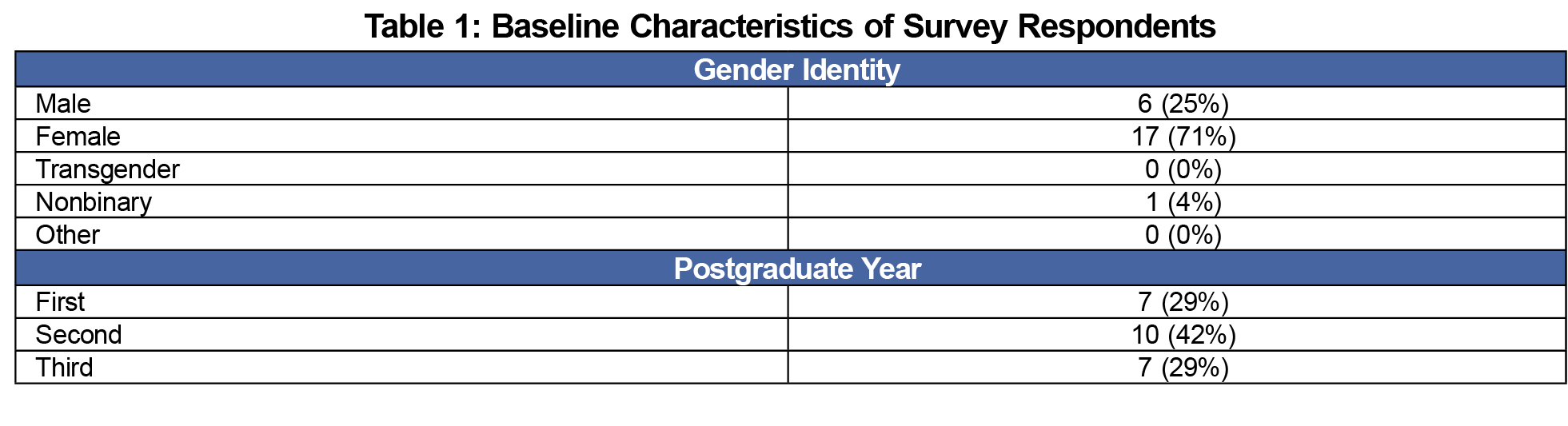

Methods: In order to decrease barriers to seeking mental health care and promote well-being among residents, the University of California Irvine Family Medicine Residency Program (UCI FMRP) implemented a program that included confidential, regular, mental health check-ins between residents and a psychiatrist. We gathered data on help-seeking behavior from an internally conducted electronic survey of 29 residents regarding perceived barriers to seeking mental health care in June, 2020.

Results: The internal survey results from 24 respondents out of 29 residents demonstrated that the program supported help-seeking behavior among the residents, with 33% of the residents requesting additional sessions with the psychiatrist and another 13% seeking external mental health resources.

Conclusion: Providing additional, confidential, on-site support may be one method of decreasing stigma, increasing access to care, and normalizing conversations around mental health in residency.

Wellness is a priority in graduate medical education since physician wellness is associated with improved outcomes for both patients and physicians.2 A scoping review of the literature on mental health of physicians and residents notes poor mental health may result in increased medical errors and the provision of suboptimal care, and that burnout and mental health concerns affect 30% to 60% of all physicians and residents.3 A meta-analysis of 26 studies found the prevalence of burnout among medical residents was 35.7%.4 Using the Maslach Burnout Inventory, a well-validated, self-administered questionnaire,3 investigators found that approximately 45.8% of practicing US physicians reported at least one burnout symptom.5

Family medicine educators strive to ensure optimal working conditions, protect resident physician well-being, and promote patient safety. Previous interventions in residency programs have included both individual and organizational strategies such as work-hour reductions, resident-led initiatives, meditation, and self-care workshops.2,6 However, a scoping review has shown that these interventions have shown little to no effect on resident burnout scores, and despite a strong focus on interventions, there was less information about barriers for seeking help.3 A large multicenter study in 2019 found that of 1,146 residents surveyed, those with burnout were more likely to find it difficult to ask for time off work for a personal health appointment.7 Furthermore, residents with high burnout scores or emotional exhaustion were more likely to find it difficult to seek professional mental health support for a serious emotional concern.7

In order to decrease barriers to seeking mental health care, promote well-being among residents, and cultivate a culture where help-seeking behavior is normalized, we implemented a program that included confidential, semiannual mental health check-ins between residents and a psychiatrist for 30-minutes and as needed check-in sessions in 2018. We hypothesized that these sessions would reduce barriers to mental-health care and services. Data on help-seeking behavior were gathered from an internally-conducted electronic survey administered by a chief resident. The purpose of this study was to assess help-seeking behavior among residents after implementing these sessions.

We collected the data presented anonymously from participants as part of a program evaluation with the intention only to provide information about the program rather than to contribute to generalizable knowledge. As such, UCI’s institutional review board determined that the project did not constitute research. We collected data from residents regarding attitudes as well as perceived barriers to accessing mental health care. We also identified whether our intervention involved a behavioral change. In order to prepare and refine our study methods, we read and discussed relevant literature.8-19

Setting

The UCI FMRP has 20 clinical faculty and 30 residents (29 at the time of the internal survey) who work in a federally-qualified health center serving the underserved of Orange County, California. Although the Office of Graduate Medical Education sends out the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) to all house staff and faculty annually and offers many wellness resources, there are no formal individual well-being check-ins.

Program Description

Semiannual 30-minute check-ins between a psychiatrist and residents were scheduled on site or remotely and referred to as the Wellness Program. Sessions were scheduled during protected resident didactic time, and the psychiatrist came on site, but was also available for virtual sessions or by telephone. During the COVID-19 pandemic, all sessions have been conducted virtually. The psychiatrist is a volunteer faculty in the department of family medicine (DFM), and has no role in resident supervision, education or evaluation. Funding for her time was provided by the DFM. All check-ins were kept confidential unless a safety issue was present. The primary structure of wellness checks involved screening for burnout and mental health issues, as well as discussing topics such as difficult encounters with patients and colleagues, imposter syndrome, test-taking anxiety, personal life challenges, work-life balance, and cultivating healthy habits and coping skills.

Drop-in times were available to residents on an as-needed basis, especially when residents needed short-term emotional support during times of crisis. If a resident needed ongoing mental health care, the psychiatrist provided referrals for community resources. Wellness checks were not mandatory, rather they were highly recommended and incorporated as part of the residency program culture. With the positive responses from the residents, the check-ins were introduced during intern orientation when each incoming intern has an introductory session with the psychiatrist.

Program Evaluation

An anonymous internal electronic survey20 was administered to residents regarding perceived barriers to self-care including mental health care in June, 2020. We used descriptive statistics, summarizing percentages of residents’ care-seeking behavior and perceived barriers to self-care.

The internal surveys were completed by 24 of 29 residents, although a few questions had only 23 responses and one question had 22. Sixty-seven percent (16/24) of the residents felt they would benefit from mental health care. Seventy-six percent (18/24) of the residents reported the check-ins made them more comfortable to seek mental health care. Thirty-three percent (8/24) of respondents reached out to the psychiatrist for additional check-ins. Three of the eight respondents who requested additional check-ins went on to access outside mental health care.

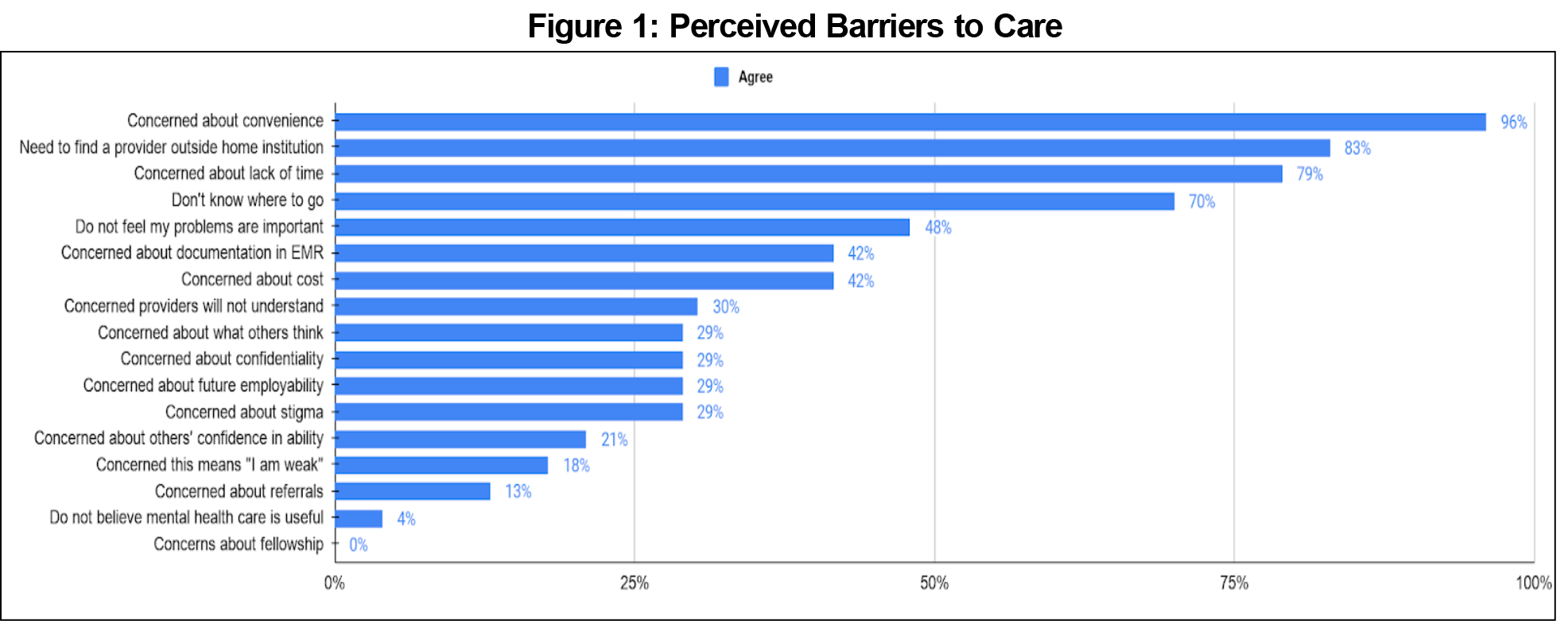

Barriers to self-care are shown in Figure 1. The most common barriers were convenience (96%, 23/24), need to find a provider outside home institution (83%, 20/24), lack of time (79%, 21/24), and not knowing where to seek available mental health resources (70%, 16/24).

The UCI FMRP’s Wellness Program was started in 2018 as a way to decrease barriers to mental health care and change the culture and perception of accessing mental health care by integrating wellness check-ins with a psychiatrist. Although most residents perceive mental health care as important (87%, n=20), our internal survey showed that there remained significant barriers to access. Despite this, 33% of residents reported requesting additional sessions with the psychiatrist beyond their two scheduled check-ins, and 13% reported going on to seek out mental care outside of the institution.

The scoping review found only four publications out of 91 that dealt with barriers to seeking and providing care for mental health concerns. There were individual barriers such as minimizing the illness, refusing to seek help, the culture of stoicism promoted among physicians, as well as stigma associated with mental illness. Structural barriers were also identified, with lack of formal support for mental well-being, poor access to counseling, lack of promotion of available wellness programs, and cost of treatment.3 Our study identified similar barriers compared to those reported in the literature. The implementation of wellness checks with a psychiatrist at our program is a unique approach intended to remove some of the barriers and supports mental health for residents as a way to prevent burnout. The Wellness Program was likely a factor in encouraging many residents to schedule additional check-ins and 13% to seek additional mental-health treatment. Providing additional, confidential, on-site support may be one method of decreasing stigma, increasing access to care, and normalizing conversations around mental health in residency.

There are several limitations in our assessment of the UCI FM residency wellness program effectiveness. First, we did not have baseline data as to how many residents accessed ongoing mental health support outside of the residency. This makes it difficult to assess the impact of this intervention on increasing access to care. A second limitation is the fact that many other program variables unfolded during the implementation of this program that could have also affected the mental health of residents, and the extent to which they sought outside care. Future directions may include a pre- and postsurvey for a particular residency cohort identifying current mental health concerns, barriers to pursuing care, and direct benefit of such a wellness intervention, while trying to minimize other programmatic variables.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the invaluable assistance provided by Mindy Smith, MD, professor of family medicine, at Michigan State University; and Argyrios Ziogas, PhD, professor, Department of Medicine, University of California, Irvine.

Presentations: Dow E, Vasa M, Hanami D, Sterling A. Semi-Annual Check-Ins with Psychiatrist Support Resident Well-Being. Poster presentation at the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Conference (Virtual), August 2020.

References

- Aaronson AL, Backes K, Agarwal G, Goldstein JL, Anzia J. Mental health during residency training: assessing the barriers to seeking care. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42(4):469-472. doi:10.1007/s40596-017-0881-3

- Winkel AF, Nguyen AT, Morgan HK, Valantsevich D, Woodland MB. Whose problem is it? The priority of physician wellness in residency training. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(3):378-383. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.10.009

- Mihailescu M, Neiterman E. A scoping review of the literature on the current mental health status of physicians and physicians-in-training in North America. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1363. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7661-9

- Rodrigues H, Cobucci R, Oliveira A, et al. Burnout syndrome among medical residents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0206840. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0206840

- Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199

- Nobleza D, Hagenbaugh J, Blue S, Skahan S, Diemer G. Resident mental health care: a timely and necessary resource. Acad Psychiatry. 2021;45(3):366-370. doi:10.1007/s40596-021-01422-1

- Dyrbye LN, Leep Hunderfund AN, Winters RC, et al. The relationship between burnout and help-seeking behaviors, concerns, and attitudes of residents. Acad Med. 2021;96(5):701-708. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003790

- Grover S, Dua D, Shouan A, Nehra R, Avasthi A. Perceived stress and barriers to seeking help from mental health professionals among trainee doctors at a tertiary care centre in North India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2019;39:143-149. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2018.12.020

- Cellini MM, Serwint JR, Chaudron LH, Baldwin CD, Blumkin AK, Szilagyi PG. Availability of emotional support and mental health care for pediatric residents. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(4):424-430. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2017.01.011

- Sofka S, Lerfald N, Reece J, Davisson L, Howsare J, Thompson J. Universal well-being assessment associated with increased resident utilization of mental health resources and decrease in professionalism breaches. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(1):83-88. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-20-00352.1

- Bommarito S, Hughes M. Intern mental health interventions. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(7):55. doi:10.1007/s11920-019-1035-y

- Thomas NK. Resident burnout. JAMA. 2004;292(23):2880-2889. doi:10.1001/jama.292.23.2880

- Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Organiz. Behav. 1981;2:99-113. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205

- Dewa CS, Jacobs P, Thanh NX, Loong D. An estimate of the cost of burnout on early retirement and reduction in clinical hours of practicing physicians in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):254. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-14-254

- Busireddy KR, Miller JA, Ellison K, Ren V, Qayyum R, Panda M. Efficacy of Interventions to Reduce Resident Physician Burnout: A Systematic Review. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(3):294-301. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-16-00372.1

- Mari S, Meyen R, Kim B. Resident-led organizational initiatives to reduce burnout and improve wellness. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):437. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1756-y

- Mortali M, Moutier C. Facilitating Help-Seeking Behavior Among Medical Trainees and Physicians Using the Interactive Screening Program. J Med Regul. 2018;104(2):27-36. doi:10.30770/2572-1852-104.2.27

- Haugen PT, McCrillis AM, Smid GE, Nijdam MJ. Mental health stigma and barriers to mental health care for first responders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;94:218-229. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.08.001

- Maslach Burnout Inventory results, UCI Graduate Medical Education, 2017-18, 2018-19, 2019-20.

- Dow E. Encouraging Mental Healthcare in Residents - Internal Survey. STFM Resource Library. Published July 14, 2022. Accessed July 18, 2022. https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/appendix-encouraging-mental-healt?CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a&tab=librarydocuments

There are no comments for this article.