Background and Objectives: Insufficient provider training contributes to health care disparities for 61 million Americans with disabilities.2,4 This study examines medical students' perceptions of their disability training and the perceived effect training has on students' preparedness to care for people with disabilities (PWD) in future practice.

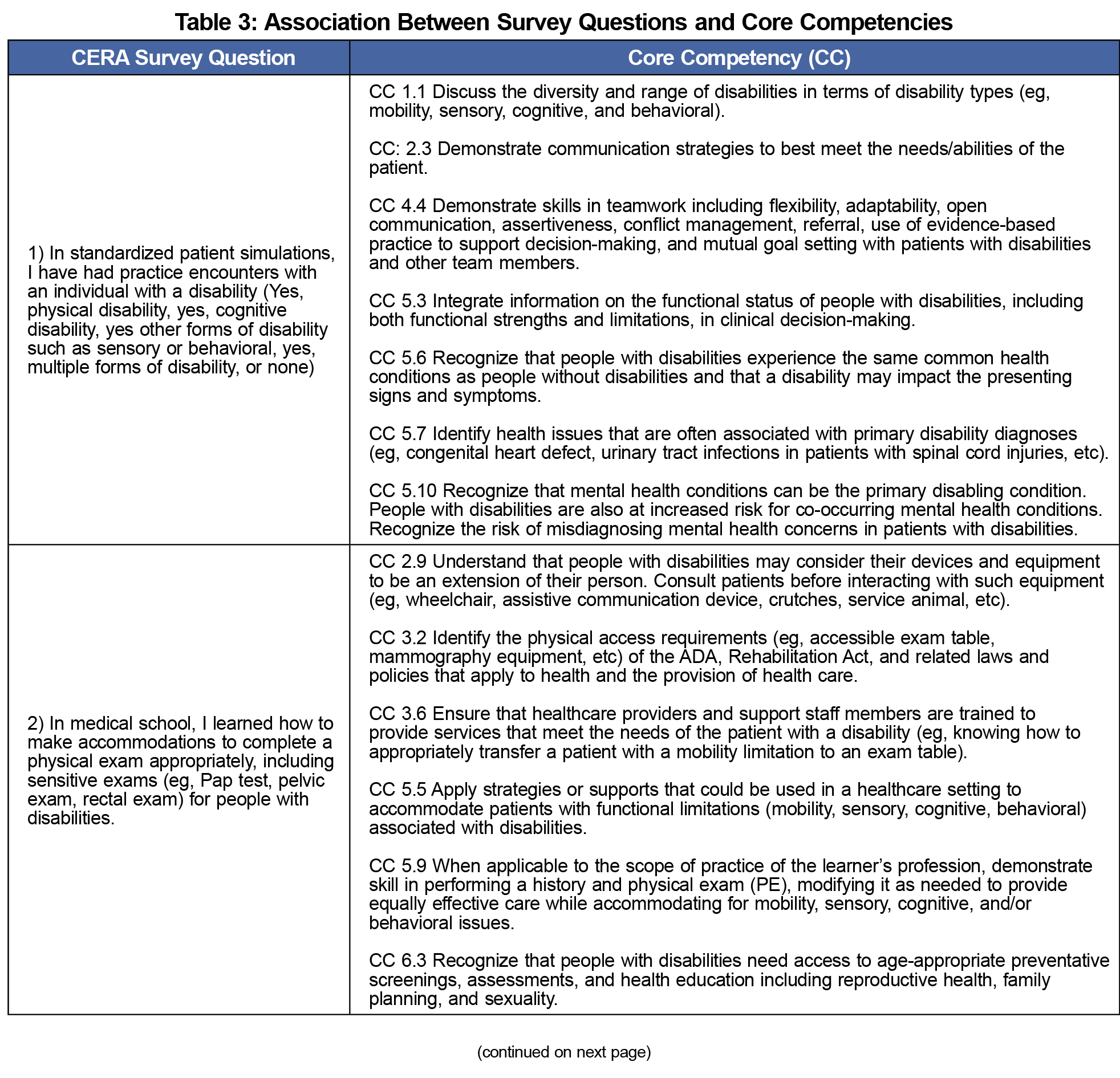

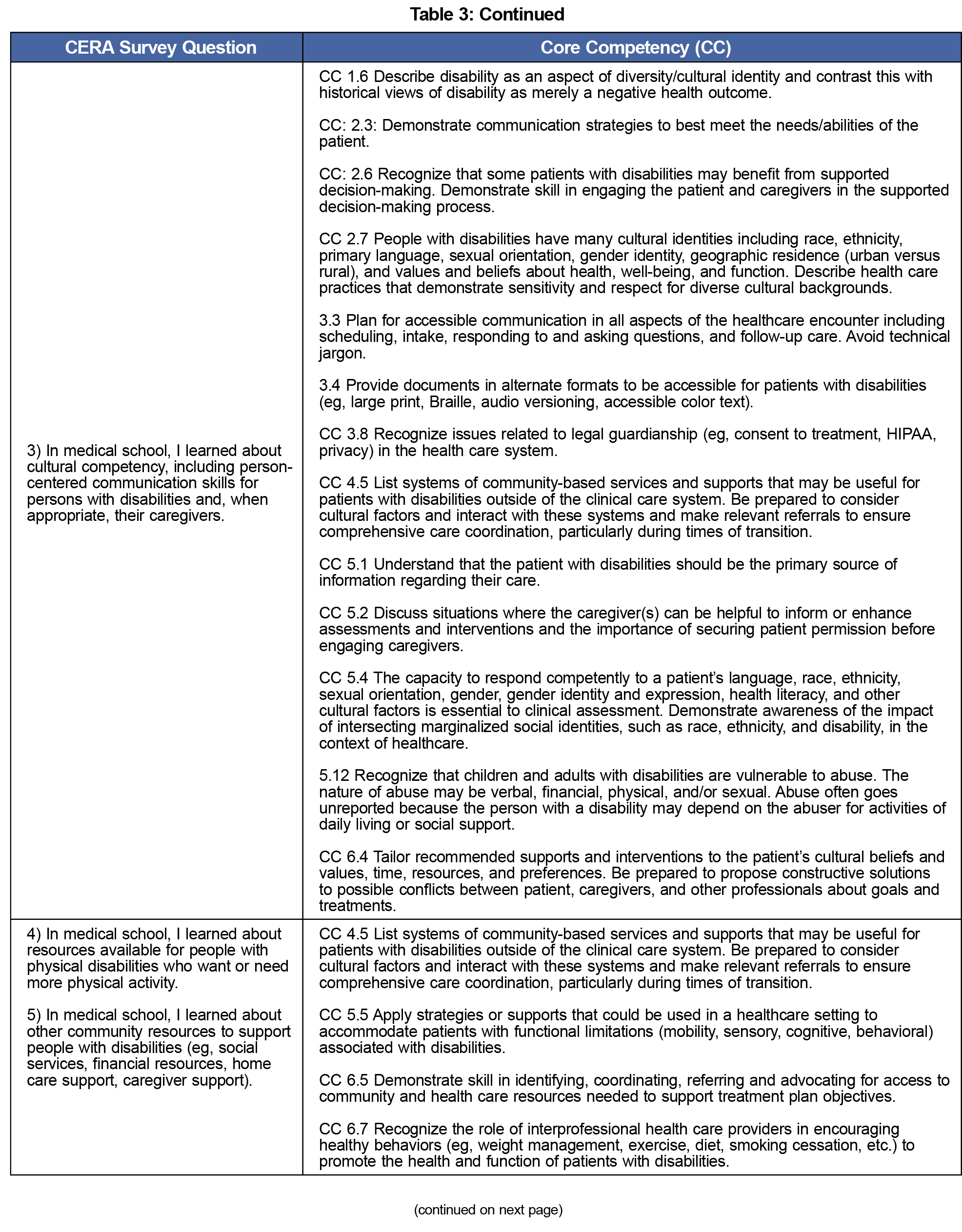

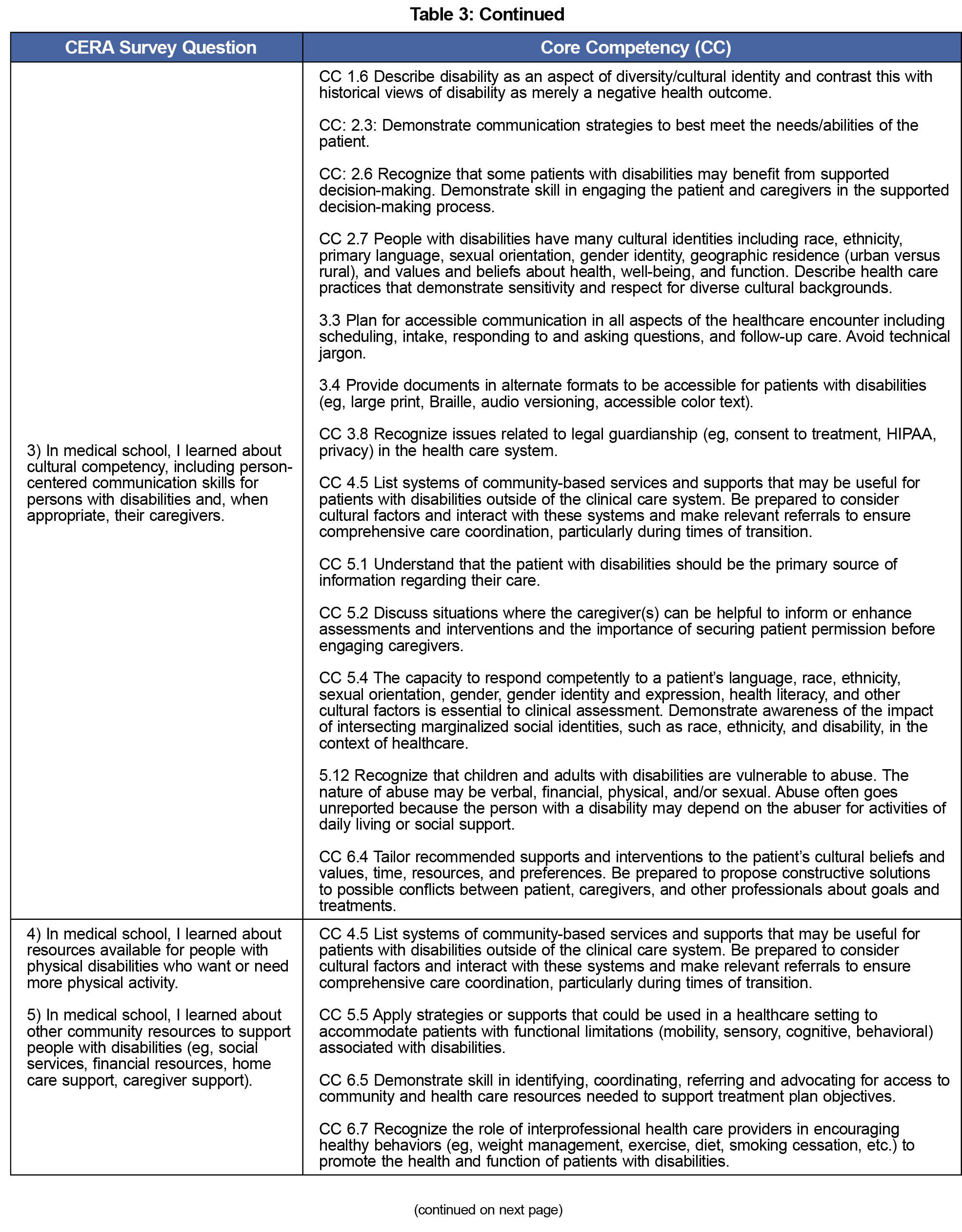

Methods: Principles of the Core Competencies on Disability for Health Care Education5 generated 10 questions. The questions were included in a survey conducted by the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) and sent to medical student members of the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). We compared responses using unadjusted χ2 tests.

Results: One hundred forty-seven surveys were returned, with 126 used for this analysis; 36% of students reported that their medical training provided them with the knowledge necessary to provide high-quality, comprehensive health care for PWD in their future practice and 97.6% agreed or strongly agreed that they needed to learn more. Six of the curricular exposures demonstrating variations of the health care needs of PWD were associated with higher percentages of medical students agreeing they are trained to perform high-quality health care for PWD in future practice.

Conclusion: Medical students continue to report deficiencies in training, knowledge, and preparedness to care for PWD. Based on the Core Competencies framework, we have identified six curricular exposures that increase readiness to care for PWD. Therefore, we recommend the Liaison Committee on Medical Education formally integrate requirements for disability training in the standards of accreditation.7

The 1990 Americans With Disabilities Act requires health care entities to provide equal access to care for those with disabilities.1 But 30 years later, only 40.7% of practicing physicians feel confident in doing so.2 Section 5307 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act acknowledges the necessity but does not mandate curricula teaching health care professionals aptitude in caring for people with disabilities (PWD).3 Insufficient disability training for providers is a recognized gap contributing to health care disparities for 61 million Americans.2,4 To address this deficiency, in 2019, the Alliance for Disability in Health Care Education developed a set of Core Competencies on Disability for Health Care Education for all practitioners.5

Our study examines medical students' perceptions of their disability training and the perceived effect training has on students' preparedness to care for PWD in future practice.

The Core Competencies5 generated 10 survey questions assessing whether current disability training in medical school meets the established standard (Table 3). We included the questions in an omnibus survey conducted by the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA). The methodology of CERA surveys has previously been described.6 The survey population was a convenience sample of medical student members of the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). The AAFP Institutional Review Board approved the study in October 2020. The AAFP delivered the survey via email, sending follow-up emails to encourage participation 11 and 18 days after the initial invitation. CERA collected data from November 3, 2020 through November 30, 2020.

Two survey questions used yes/no dichotomous answers, and eight of the 10 questions used a 4-point Likert scale. We collapsed Likert-scale answers to agree vs disagree for bivariate analyses. We used unadjusted χ2 tests to compare responses and Stata 15.0 (StataCorp, LLP) with a two-sided α value of 0.05 for all analyses.

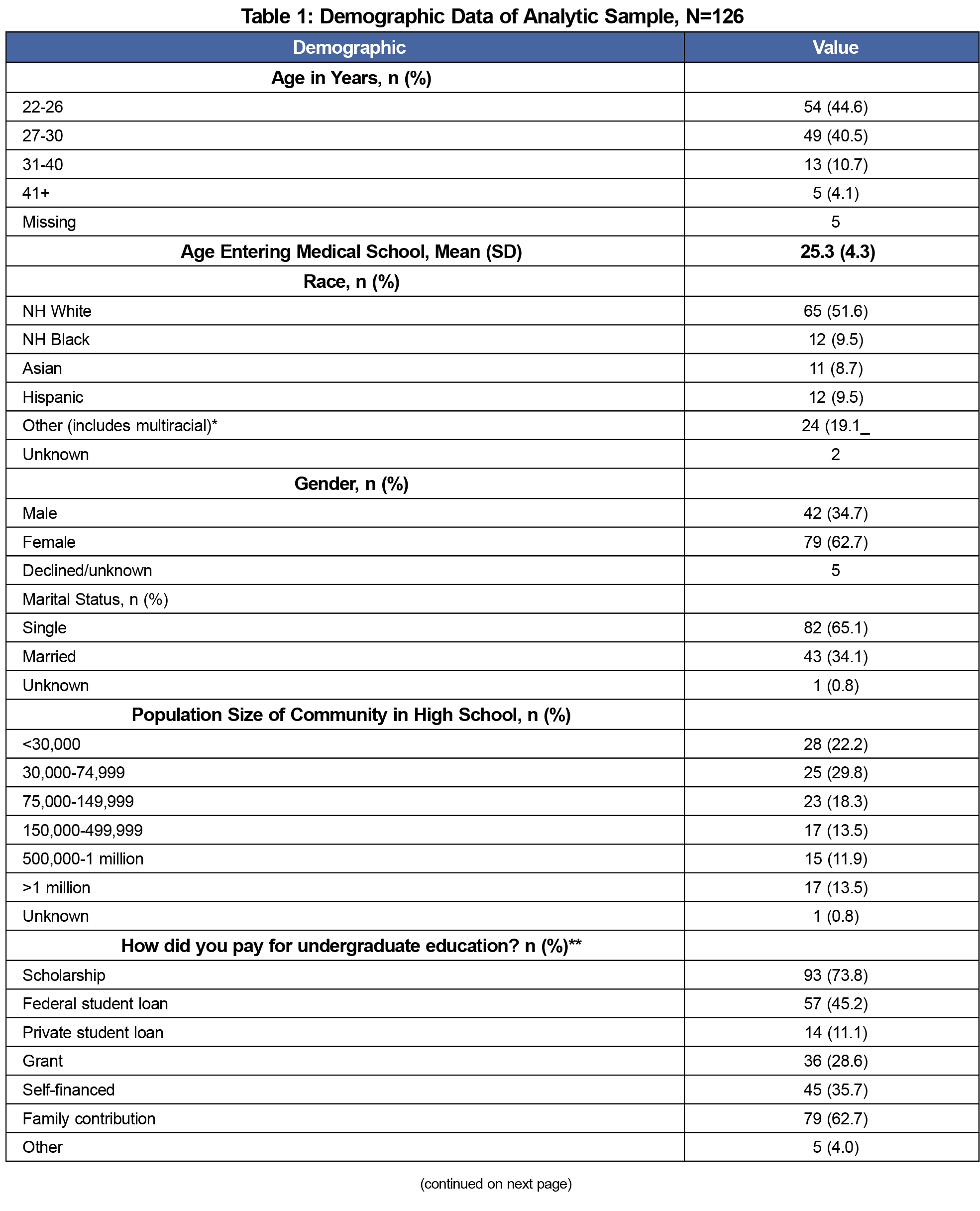

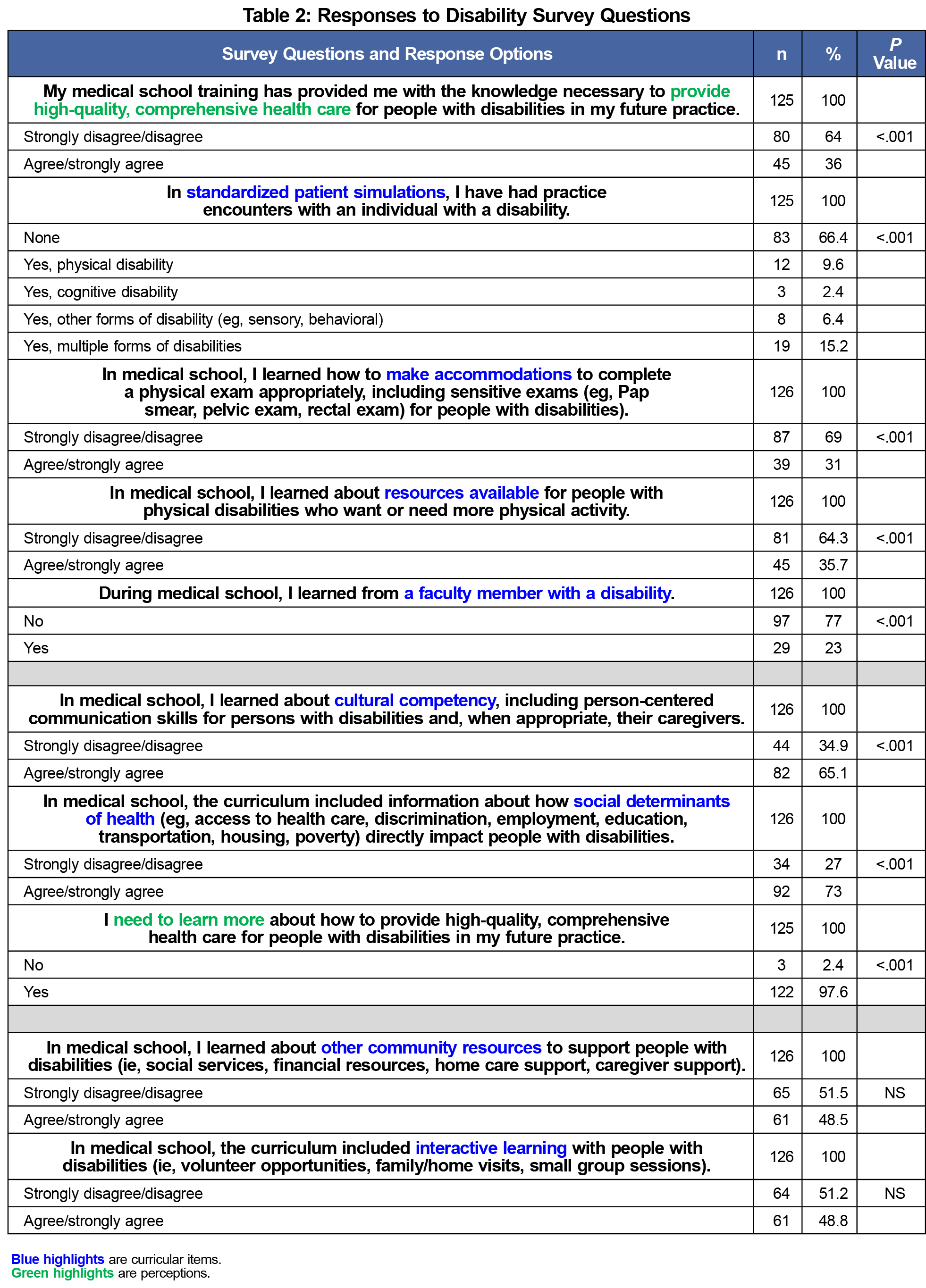

One hundred forty-seven students responded to the survey, with 126 (85%) answering the disability-related questions, making them eligible for inclusion in the analysis. Most respondents were under 30 years of age, White, female, single, in the last 2 years of medical school, receiving an MD degree, and without a self-disclosed disability (Table 1). The minority of students felt that their medical school training provided the necessary knowledge to provide high-quality, comprehensive health care for PWD (36% vs 64%, P<.001, Table 2), and the majority agreed that they need to learn more (97.8% vs 2.4%, P<.001, Table 2).

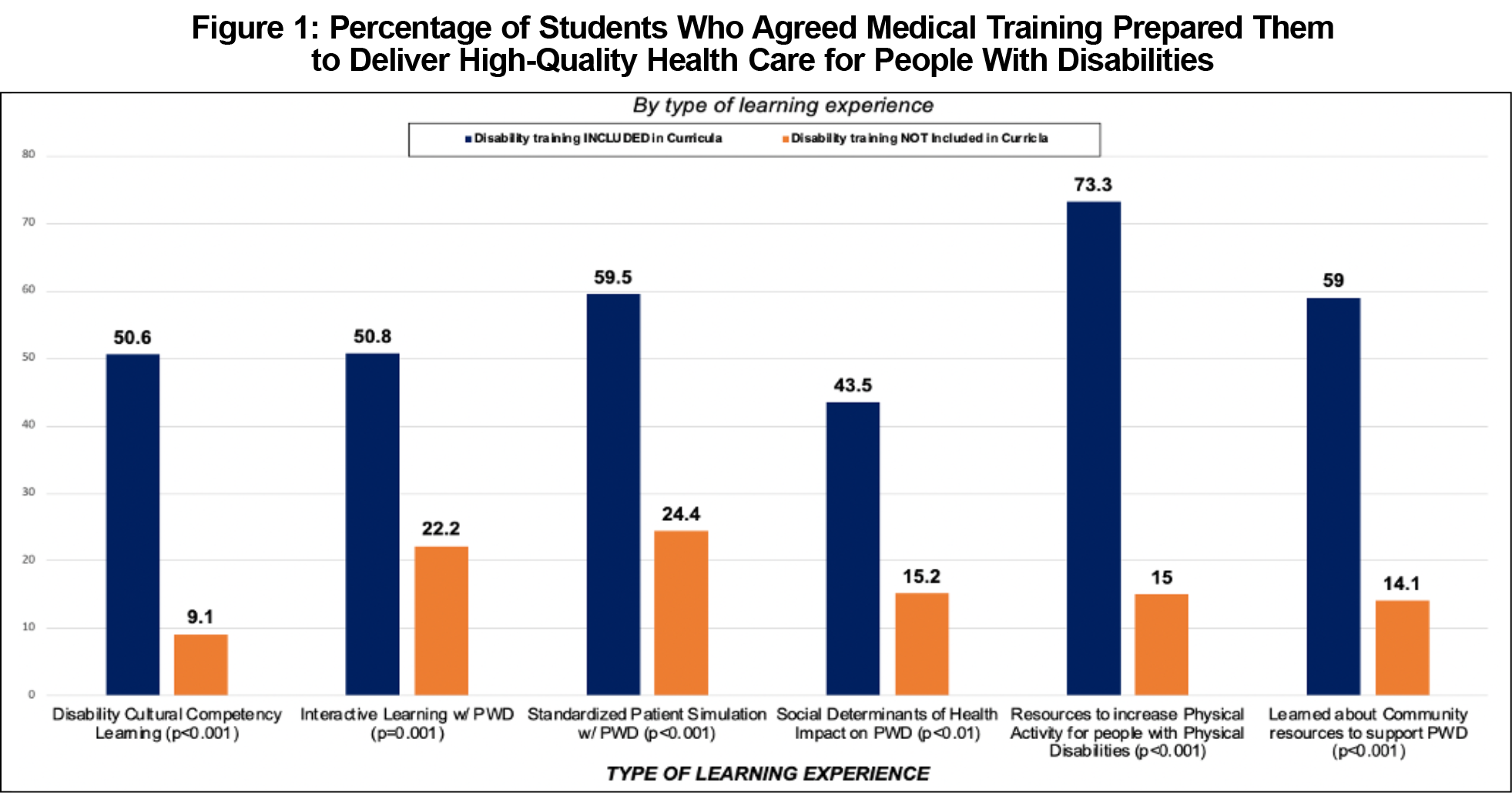

Four curricular elements were absent from most students' disability education (Table 2). Students reported no simulation training with a PWD (P<.001), reported not learning how to make accommodations to complete a physical exam, including the sensitive parts, for PWD (P<.001); reported not learning about resources available for PWD to increase physical activity (P<.001); and reported not having exposure to a faculty member with a disability (P<.001).

Notably, offering students the above curricular experiences leads to positive results. Including PWD in simulated patient encounters (Figure 2) is associated with greater skills in making accommodations during physical exams (P=.005) and greater confidence in preparedness for the future care of PWD (P<.001). The students who reported other forms of interactive learning opportunities with PWD were more likely to report that their medical training prepared them to provide high-quality care for PWD in future practice than those without such opportunities (P=.001) and were more likely to be aware of community resources (P=.010), as well as resources for patients with physical disabilities who want or need more activity (P<.001).

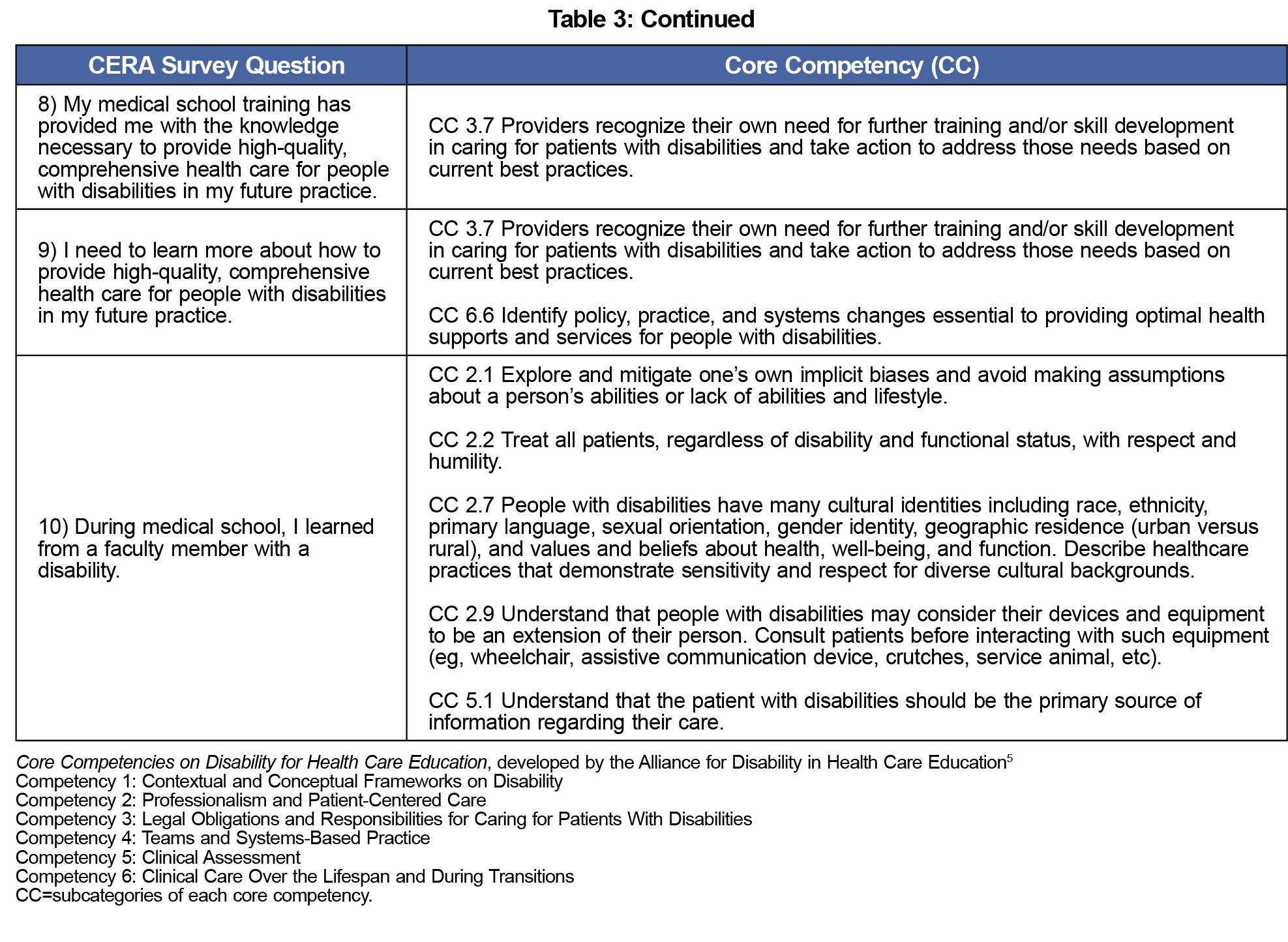

The 36% of students who agreed that their medical school training provided them with the knowledge necessary to provide comprehensive health care for PWD experienced six different educational exposures during medical school that they shared (Figure 1).The common exposures include (1) "learned cultural competency," including person-centered communication skills for PWD (P<.001); (2) "interactive learning with PWD" through family/home visits or small group sessions (P<.001); (3) "practice encounters with PWD through patient simulations" (P<0.001); (4) learning about "the impact of social determinants of health on PWD" (P<.001); (5) learning about "resources for PWD for physical activity" (P<.001); and finally (6) learning about "community resources to support PWD," such as social services or caregiver support (P<.001). Importantly, all six of the curricular exposures demonstrating variations of the health care needs of PWD were associated with higher percentages of medical students agreeing they are trained to perform high-quality health care for PWD in practice.

Medical students continue to report deficiencies in training, knowledge, and preparedness to care for PWD. Based on the Core Competencies framework, we have identified six curricular exposures that increase readiness to care for PWD. All six of these curricular exposures can be taught via interactive learning opportunities by including people with disabilities and/or their caregivers/families. Future hypotheses about whether interactive learning opportunities are the best way to integrate the above-mentioned six educational exposures, or one of many to be named, must be studied.

Strengths of the study include alignment with the Core Competencies5 and illustrate a reflection of current training practices. Limitations include the use of a convenience sample of medical students interested in family medicine. As such, the results are not generalizable to a greater population and may not be reproducible in a future survey. However, the results support other prior studies and indicate a need for more specific disability training in medical school.2,4 Our results do not illustrate what type of learning experience is most effective in teaching the Core Competencies.5 Medical students' perceptions of preparedness to care for PWD do not necessarily correlate with improved patient outcomes, and future research is needed in this area as well.

Previous research suggests the most effective approach to disability competence recognizes disability as an aspect of population diversity akin to race or ethnicity.2,4 We suggest using the Core Competencies as a guide to include formal discussions of health equity, patient-centered care, social determinants of health, intersectionality, and cultural competence around PWD in all medical school curricula, and recommend the Liaison Committee on Medical Education formally integrate requirements for disability training in the standards of accreditation.7

Acknowledgments

Presentations: This study was previously presented as follows:

- Poster presentation, 2021 Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference, May 2021 (virtual).

- Poster presentation, 43rd Annual Michigan Family Medicine Research Day, May 27, 2021 (virtual).

- Poster presentation, NAPCRG 49th Annual Conference, November 19, 2021 (virtual), and abstract published in Annals of Family Medicine.

References

- Prohibition of Discrimination by Public Accommodations, 42 USC § 12182(a) (2010). Accessed August 18, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2010-title42/pdf/USCODE-2010-title42-chap126-subchapIII-sec12182.pdf

- Iezzoni LI, Rao SR, Ressalam J, et al. Physicians’ perceptions of people with disability and their health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(2):297-306. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01452

- Health equity framework for People with Disabilities. National Council on Disability. February 28, 2022. Accessed March 29, 2022. https://ncd.gov/publications/2022/health-equity-framework

- Havercamp SM, Barnhart WR, Robinson AC, Whalen Smith CN. What should we teach about disability? National consensus on disability competencies for health care education. Disabil Health J. 2021;14(2):100989. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.100989

- Core Competencies on Disability for Health Care Education. Alliance for Disability in Health Care Education. June 2019. Accessed August 18, 2022. https://nisonger.osu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/post-consensus-Core-Competencies-on-Disability_8.5.19.pdf

- Seehusen DA, Mainous AG III, Chessman AW. Creating a Centralized infrastructure to facilitate medical education research. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):257-260. doi:10.1370/afm.2228

- Lunsford CD, Tolchin DW, Meeks L. Unpublished Letter to Drs Barzansky and Catanese. December 3, 2021.

There are no comments for this article.