Introduction: Bullying behavior in residency is common, with prevalence rates ranging from 10% to 48%. Negative acts adversely impact junior physicians. The aims of this study were to examine (a) gender differences in experiences of bullying and/or negative acts while working as a medical resident, (b) residents’ perceptions of injunctive (ie, approval of) and descriptive (ie, behavior) norms related to reporting bullying behaviors, and (c) whether greater self-other differences predict greater engagement in reporting bullying behavior by others in the workplace.

Methods: Self-report surveys were administered to family medicine, internal medicine, surgical, and emergency medicine residents (N=61).

Results: Female residents reported experiencing significantly more bullying than males. Overall, resident physicians held inaccurate beliefs, and thought other residents reported bullying more often than they did. Finally, the degree of inaccuracy was associated with reporting bullying behavior.

Conclusion: These findings are an initial indication that normative interventions may be applicable with this population. In a field that struggles with high rates of burnout, finding ways to improve the culture of an organization may assist with addressing at least part of these systemic issues.

Bullying behavior in residency is common, with prevalence rates ranging from 10% to 48%.1,2 Negative acts adversely impact junior physicians and increase risk of job dissatisfaction, burnout, strain on mental health, and accidents at work.1,3,4 Reporting behavior and shifting the perception of retaliatory threat might be one way to shift the abusive dynamic known in graduate medical education.

Decades of social norms research has identified the tendency of individuals to conform to peer norms and use others as a guidepost for their own behaviors. The theory of reasoned action, and later, the theory of planned behavior, have highlighted the role of social norms as a determinant of engagement in behaviors.5–8 Social norms have been delineated into descriptive norms (ie, how often one is engaging in a particular behavior) and injunctive norms (ie, how acceptable a behavior is perceived to be). Self-other discrepancies (how inaccurate one’s own normative estimate is compared to the reference group) have been shown to predict others’ tendencies to engage in a particular behavior over time. Social norms interventions aiming to modify one’s perceived norms of the reference group have also resulted in shifts in behavior across a variety of domains.9,10

The aims of our study were to examine (a) gender differences in experiences of bullying and/or negative acts while working as a medical resident, (b) resident perceptions of injunctive (ie, approval of) and descriptive (ie, behavior) norms related to reporting bullying behaviors, and (c) determine whether greater self-other differences predict greater engagement in reporting bullying behavior by others in the workplace.

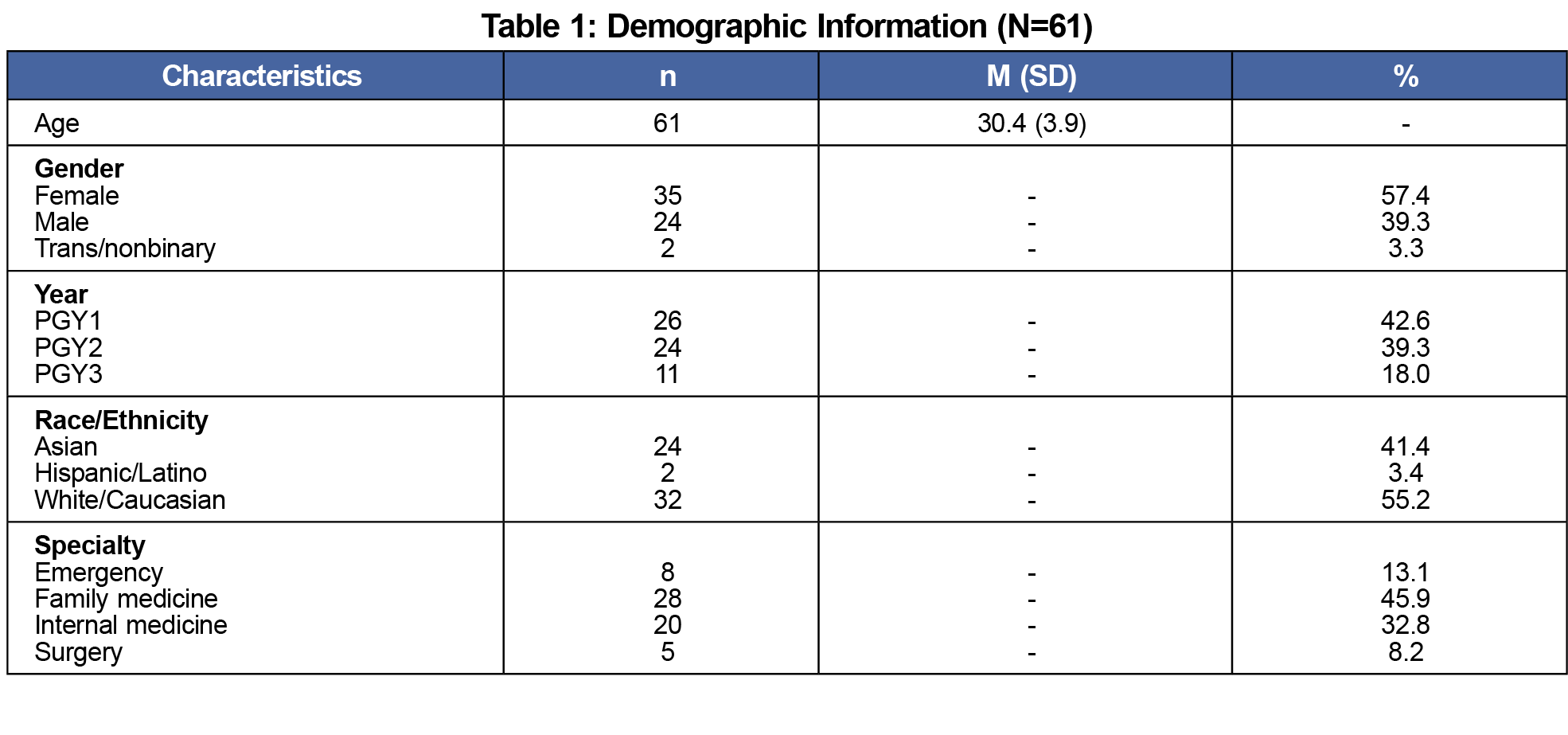

Participants included a convenience sample of 61 medical residents (59% response rate) at two rural teaching hospitals. See Table 1 for demographic information. The research was approved by the institutional review boards of the associated institutions. An electronic survey included questions about demographic information, experiences of bullying/negative acts, and perceived norms related to reporting behavior.

We used the Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R)11 to assess residents’ experiences of bullying and negative acts by others within their work environment. Respondents determine whether they have been exposed to a negative act that is listed from 0 (never) to 4 (daily). This measure has been established as an adequate and reliable tool and measures personal bullying, work-related bullying, and experience of physical intimidation. It has been previously used with samples of health care workers.11 Total scale reliability estimates for this sample were high (α=.95) as were subscale reliability estimates (α=.94, .84, and .71, respectively).

Four additional questions were used to examine self and other injunctive and descriptive norms for reporting negative acts over the past 6-months. Descriptive norms questions were rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (never reported, mentioned, or addressed) to 5 (always). Injunctive norms questions were rated as 1 (completely unacceptable) to 5 (completely acceptable). These questions are similar to a precedent established in other studies that make use of paralleled personal frequency estimates.12

Analysis Plan

We used one-way analysis of variance to examine differences in bullying behavior among medical residents. Paired t tests examined the accuracy of residents’ perceptions of descriptive and injunctive norms of their peers.

We calculated self-other differences (SODs) for injunctive and descriptive norms. To calculate the descriptive SOD, the estimate of peer frequency of reporting behavior was subtracted from self-reported frequency of behavior. To calculate injunctive SODs for respondents, estimates of peer attitudes/acceptance of reporting behavior was subtracted from self-estimate of attitude. We used paired sample t tests to compare the magnitude of SODs by norm type (descriptive or injunctive). We used independent samples t tests to make comparisons of SODs by gender.

Respondents were primarily first year (n=26, 42.6%) female (n=35, 57.4%), and White (n=32, 55.2%) residents working in family medicine (n=28, 45.9%). See Table 1 for a list of demographic characteristics. Residents indicated they were an average of 30.4 (SD=3.9) years old.

Bullying Behavior and Gender

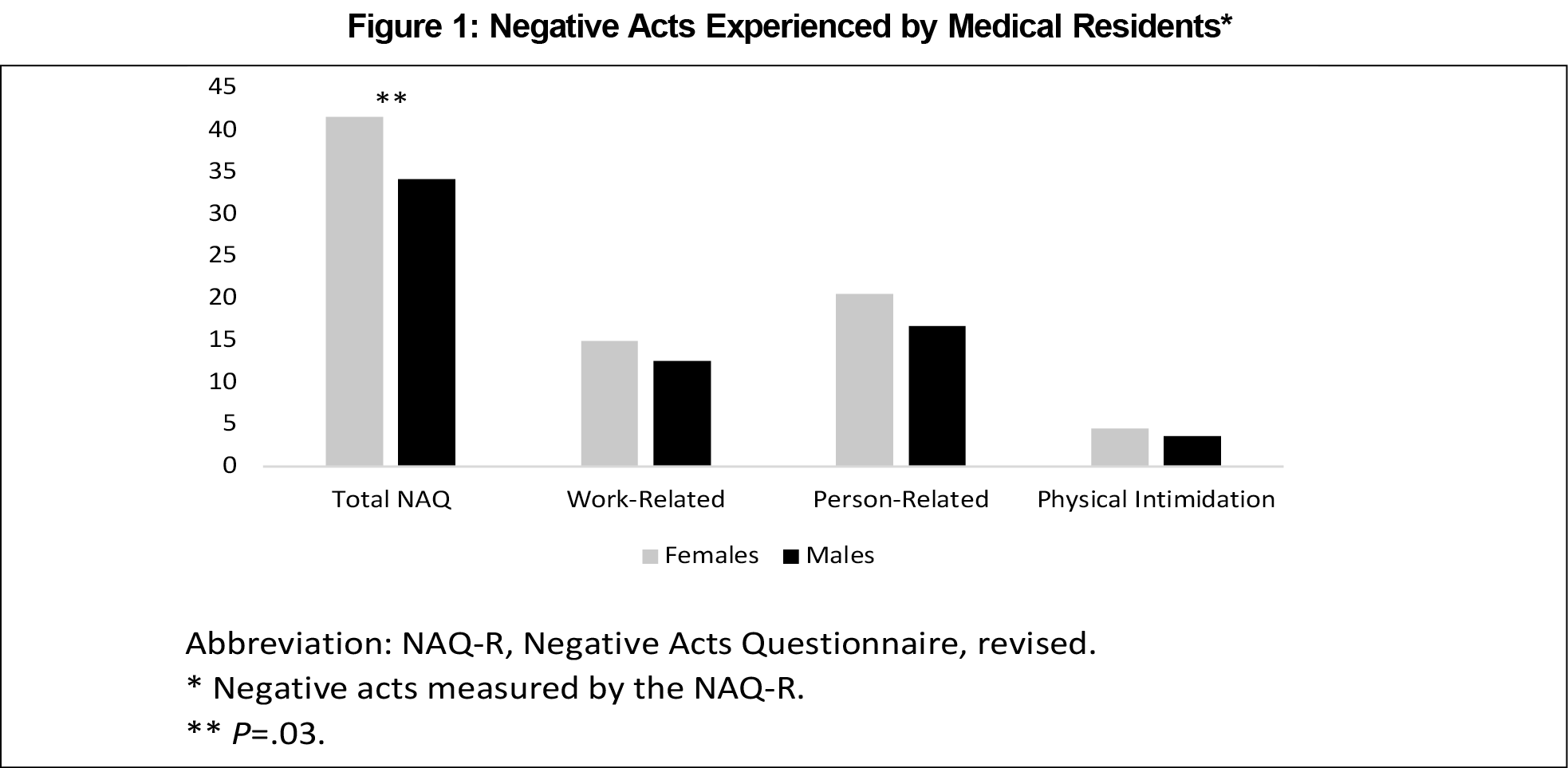

There were significant differences in the total score on the Negative Acts Questionnaire between males and females (F[2, 57]=2.52, P=.05), such that females reported experiencing significantly more negative acts compared to their male counterparts overall. Findings remained significant after controlling for race/ethnicity. There was a significant difference between males and females on the Work-Related Bullying subscale (F[2, 57]=2.52=3.92, P=.03), such that women reported more negative treatment (eg, greater work load, excessive monitoring of work, having opinions ignored, or being ordered to work below level of competence; see Figure 1 and Table 2). Exploratory analyses indicated there were no significant differences in the total score based on location, year in residency, and program type.

Accuracy of Peer Predictions

Residents significantly overestimated how often their peers reported inappropriate or bullying behavior by superiors (t[59]=-4.19, P<.01, self M=1.64, SD=1.03), and estimate of peers (M=2.37, SD=1.08). In other words, residents perceived that their peers actually reported bullying behavior more often compared to themselves.

Paired t tests examining injunctive norms indicated that residents inaccurately estimated peers’ acceptance of reporting of bullying behavior (t[59]=2.89, P<.01, self M=4.08, SD=1.16), and estimate of peers (M=3.80, SD=1.00). Residents perceived their peers to have less favorable attitudes toward reporting negative acts and bullying compared to themselves.

Respondents’ estimates of SODs differed by norm type (t[59]=-5.28, P<.01), such that individuals were more inaccurate estimating peer attitudes compared to estimating actual behavior. There were no significant differences in SODs by gender.

Associations Between SODs and Reporting Bullying

We used linear regression to determine whether the degree of exaggeration or minimization (SODs) was significantly associated with residents' own tendency to report bullying behavior. SODs of both norm types were significantly associated with reporting negative acts or bullying (F[2,60]=22.32, P<.001, R2=.44). Descriptive SODs were positively associated with reporting behavior (r[61]=.63, P=.01). That is, the more others inaccurately perceived that those around them were reporting negative acts, the more likely they were to report behaviors themselves.

This study resulted in several findings. First, female residents reported experiencing significantly more bullying than males. Second, resident physicians held inaccurate beliefs, and thought other residents reported bullying more often than they did. Finally, the degree of inaccuracy was associated with reporting bullying behavior. That is, the residents who believed that bullying or negative acts were often or always reported by their peers were more likely to report bullying they experienced themselves.

Findings that female residents reported more frequent bullying behavior is consistent with other research that suggests that women are disproportionately impacted by negative acts and bullying behavior in medicine.13 Our findings remained even after controlling for race/ethnicity, a well-established correlate of discrimination and differential treatment in the broader community and in medicine. Bullying and differential treatment is medicine is associated with psychological distress and negatively impacts the organization.14 Examining longer-term impacts on performance and/or mental health may also be useful to guide outcome measures for future interventions.

The finding that residents who perceived their peers to engage in more frequent reporting behavior were more likely to report bullying is an initial indication that normative interventions may be applicable with this population. Numerous studies have used social norms interventions to successfully modify behavior. These interventions aim to shift the belief or correct inaccuracies as a strategy to “draw up” (or down) a behavior over time. Less is understood about the impact of bullying interventions within residency programs. Future research might examine whether interventions using social norms during training could reduce such common and harmful behavior. For example, interventions might alter perceptions to enhance the belief that peers are reporting bullying behavior to increase reporting behavior over time.

There are numerous negative health consequences of bullying in health care.14 In a field that struggles with high rates of burnout, finding ways to improve the culture of an organization may assist with addressing at least some of these systemic issues.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. It is possible that individuals who were concerned about retaliation may have been less likely to complete the survey. This study also had a small convenience sample, which might limit the generalizability of these findings. Finally, these data do not allow for conclusions about what each gender considers acceptable or not. That is, one gender may be less likely to perceive actions as inappropriate and consistent with normative behavior, which would not allow for detection of those negative acts.

References

- Paice E, Smith D. Bullying of trainee doctors is a patient safety issue. Clin Teach. 2009;6(1):13-17. doi:10.1111/j.1743-498X.2008.00251.x

- Chadaga AR, Villines D, Krikorian A. Bullying in the American graduate medical education system: a national cross-sectional survey. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0150246-e0150246. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0150246

- Samsudin EZ, Isahak M, Rampal S. The prevalence, risk factors and outcomes of workplace bullying among junior doctors: a systematic review. Eur J Work Organ Psychol. 2018;27(6):700-718. doi:10.1080/1359432X.2018.1502171

- Gredler GR, Olweus D. Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Psychol Sch. 2003;40(6):699-700. doi:10.1002/pits.10114

- Ajzen I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In: Kuhl J, Beckman J, eds. Action-Control: From Cognition to Behavior.Springer; 1985:11-39. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-69746-3_2

- Ajzen I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2002;32(4):665-683. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00236.x

- Ajzen I, Madden TJ. Prediction of goal-directed behavior: Attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1986;22(5):453-474. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(86)90045-4

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research.Addison-Wesley; 1975.

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: a meta-analytic integration. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64(3):331-341. doi:10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331

- Gerber AS, Rogers T. Descriptive social norms and motivation to vote: everybody’s voting and so should you. J Polit. 2009;71(1):178-191. doi:10.1017/S0022381608090117

- Anusiewicz CV, Li P, Patrician PA. Measuring workplace bullying in a U.S. nursing population with the Short Negative Acts Questionnaire. Res Nurs Health. 2021;44(2):319-328. doi:10.1002/nur.22117

- Park HS, Smith SW. Distinctiveness and influence of subjective norms, personal descriptive and injunctive norms, and societal descriptive and injunctive norms on behavioral intent: A case of two behaviors critical to organ donation. Communic Res. 2007;33:194-218.

- Zhang LM, Ellis RJ, Ma M, et al. Prevalence, types, and sources of bullying reported by US general surgery residents in 2019. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2093-2095. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2901

- Lever I, Dyball D, Greenberg N, Stevelink SAM. Health consequences of bullying in the healthcare workplace: A systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75(12):3195-3209. doi:10.1111/jan.13986

There are no comments for this article.