Background and Objectives: This study examined changes over time in the shortage and quality of clinical training sites for students. The surveys provided baseline and milestone measurements for the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine’s (STFM) Preceptor Expansion Initiative.

Methods: Data were gathered in 2016 and again in 2020, through the Council of Academic Family Medicine’s (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of family medicine clerkship directors. Clerkship directors answered questions concerning number of students requiring placement, number of precepting sites used, frequency of negative comments about family medicine as a specialty, and about opportunities for students to experience comprehensive care, patient-centered care, and document in electronic health records.

Results: The number of students who annually required placement at family medicine preceptor sites increased slightly from 2016 to 2020, but the number of sites utilized per family medicine department did not. There were no changes in the percentage of sites having Patient-Centered Medical Home or similar recognition or providing comprehensive care with or without obstetrics. However, more students were allowed to enter data and write patient encounter notes in 2020 than in 2016.

Conclusions: Clerkship directors continue to struggle to find high-quality family medicine training sites for students. STFM’s Preceptor Expansion Initiative has made strides to help students become active, productive members of care teams, to reduce the administrative burden of teaching, and to promote the precepting of multiple students at once.1 These efforts to incentivize precepting are ongoing, but won’t be enough to compensate for the rapid growth in the number of students and the increasing demands on physicians for high-volume patient care.

In late 2015, the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) launched a multiyear, interprofessional, interdisciplinary Preceptor Expansion Initiative to address the shortage and quality of clinical training sites for students. The aims were to decrease the percentage of primary care clerkship directors who report difficulty finding clinical preceptor sites, and increase the percentage of students completing clerkships at high-functioning sites.1

Over the past several years, the Preceptor Expansion Initiative has celebrated many successes, including a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) change to student documentation requirements, an American Board of Family Medicine Precepting Performance Improvement Program, and resources for standardized onboarding of students and preceptors.2 However the challenge to place students in clinical sites remains.3

This study examined changes in the shortage and quality of family medicine clinical training sites for students from 2016 to 2020. The surveys provided baseline and milestone measurements for STFM’s Preceptor Expansion Initiative.

Data were gathered in 2016 and again in 2020, through the Council of Academic Family Medicine’s (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of family medicine clerkship directors.4 Clerkship directors answered demographic questions, questions about the level of difficulty finding preceptor sites, and questions related to the quality of the precepting experience: how often students heard criticism of family medicine as a specialty during their clerkships, whether students were rotating at sites providing comprehensive care, and whether students had the opportunity to document patient visits in electronic health records (EHR). We hypothesized that it would be just as difficult to find precepting sites in 2020 as it was in 2016, more students would be writing patient notes in EHRs, there would be fewer criticisms of family medicine as a specialty, and there would be fewer sites offering comprehensive care.

The baseline survey was emailed to 125 US and 16 Canadian family medicine clerkship directors on August 9, 2016. The survey closed on October 9, 2016. The overall response rate was 86%.1

The 2020 survey was emailed to 147 US and 16 Canadian family medicine clerkship directors on June 1, 2020 and closed on June 25, 2020. The overall response rate was 64%. Clerkship directors were asked to answer the questions based on the clerkship's curriculum prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The American Academy of Family Physicians’ Institutional Review Board approved both studies.

For the 2020 survey, “most clerkship directors were female (60%), White (79%), and averaged 31% protected time as clerkship director. Clerkships were primarily block only and were either 4 (41%) or 6 (34%) weeks long.”5 Demographic data were similar to the 2016 survey.1

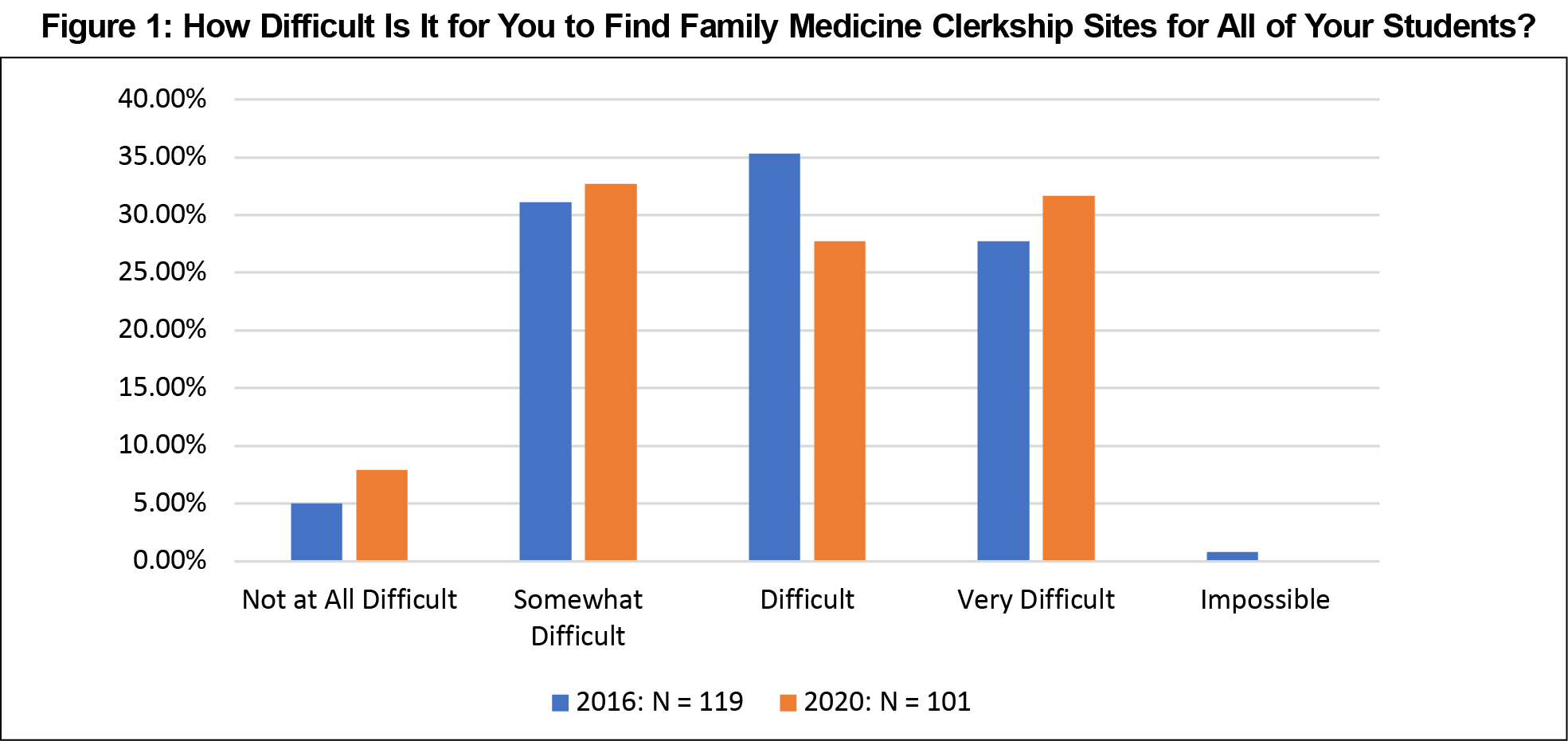

Independent samples t tests showed the average number of students that clerkship directors needed to place annually at family medicine preceptor sites increased from 2016 to 2020, but the increase was not statistically significant (133 vs 149, P=.141). In other words, class sizes remained fairly consistent at the surveyed schools. The number of sites utilized per family medicine department did not change from 2016 to 2020 (44.4 vs 42.8, P=.819). Mann-Whitney U tests showed no difference in the reported level of difficulty finding placements for students (P=.715, Figure 1). Clerkship directors continued to have difficulty finding sites for their students.

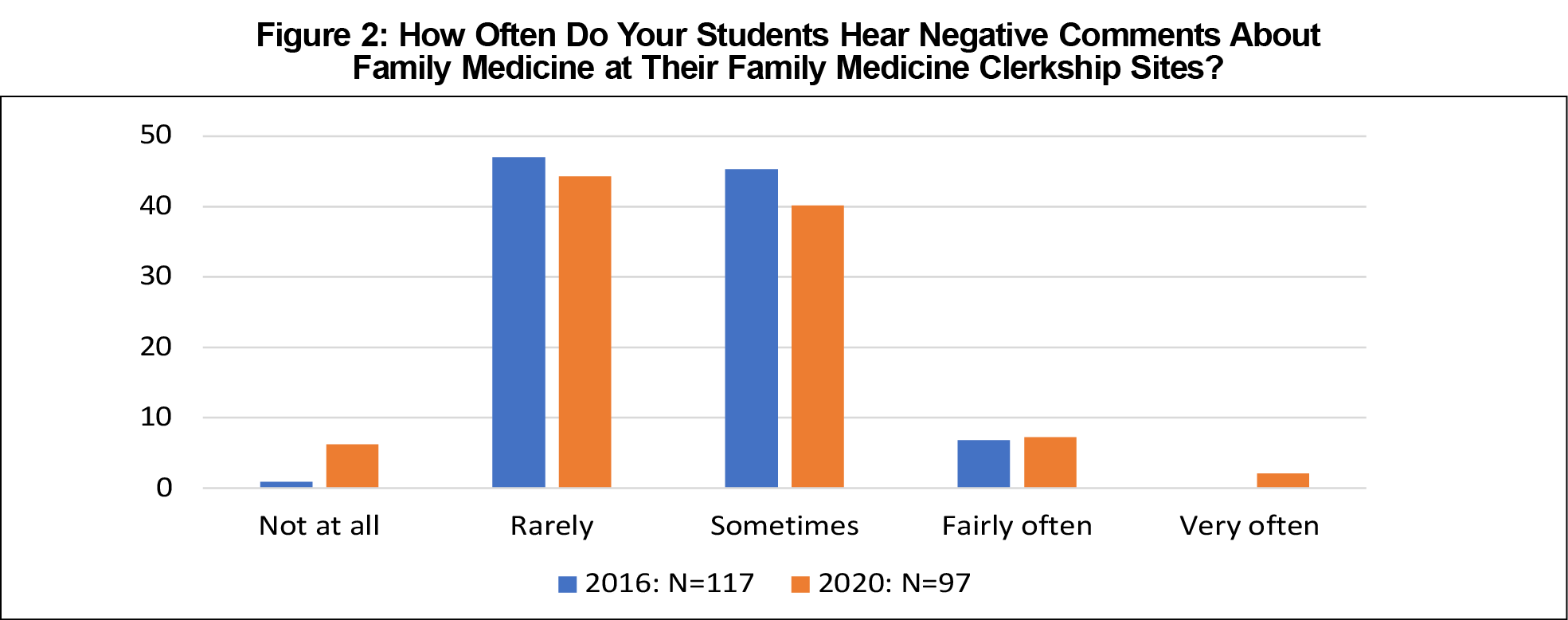

Table 1 shows changes in students’ clinical experiences from 2016 to 2020 in family medicine clerkships. The only statistically significant changes were in the percentage of precepting sites that allow students to use the EHR. More students were allowed to enter data (64.8% vs 74.7%, P=.019) and write patient encounter notes in the EHR (57.1% vs 71.7%, P=.001) in 2020 than in 2016. Mann-Whitney U tests showed no change in the frequency of students hearing negative comments about the specialty of family medicine (P=.619, Figure 2).

Clerkship directors continue to have difficulty finding clinical sites for students. This is not surprising since US MD-granting school enrollment grew 33% between 2002-2003 and 2019-2020,3 and the number of new DOs set a record in 2019, with nearly 7,000 new physicians graduating from osteopathic medical schools.7 Unexpectedly, there was no statistical difference in the reported level of difficulty in finding placements for students from 2016 to 2020. This could be an indication that STFM’s Preceptor Expansion Initiative is making an impact, although the reason this measurement has held steady (at a challenging level) is likely multifactorial. Deans at US MD-granting schools continue to express concern about the number of clinical training sites and the supply of qualified primary care preceptors.3

There were no changes in clerkship directors’ estimation of the percentage of precepting sites having Patient-Centered Medical Home or similar recognition or providing comprehensive care with or without obstetrics. However, more students were allowed to enter data and write patient encounter notes in 2020 than in 2016. This is likely a result of changes to CMS guidance for claims processing— that went into effect in February 2018—to allow the “teaching physician to verify in the medical record any student documentation of components of E/M services, rather than redocumenting the work.”6 Previous guidance prohibited teaching physicians from referring to student documentation of physical exam findings or decision-making. Representatives of STFM’s Preceptor Expansion Initiative had requested this change, and CMS agreed that the previous language was burdensome.2,6

With the decline in the number of family physicians providing OB services8 and pending changes to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s family medicine program requirements around scope of practice modeling and training,9 STFM may need to eliminate the provision of OB care in training sites as a quality metric for the Initiative.

Our study had several limitations. First, respondents for the 2020 survey were not necessarily the same clerkship directors who responded to the 2016 survey, due to turnover, the opening of new medical schools, and individual choices on whether or not to respond to the survey request. Also, clerkship directors received the 2020 survey in June and were asked to answer questions based on their experience prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, rather than their most recent experience. And, finally, for the survey questions about quality of clinical training sites, most clerkship directors indicated their responses were estimates, rather than based on actual data.

Finding enough high-quality family medicine training sites remains a challenge, and there doesn’t appear to be any national shift away from the current model of education, where medical schools and other health profession training schools compete for one-to-one clinical training opportunities with volunteer faculty. Nearly 70% of physicians are now employed by hospitals or corporations,10 which, for reasons related to both administrative policies and productivity requirements, may limit their ability to accept medical students.

STFM’s Preceptor Expansion Initiative has helped students become active, productive members of care teams, to reduce the administrative burden of teaching, and to promote the precepting of multiple students at once.1 These efforts to incentivize precepting are ongoing, but won’t be enough to compensate for the rapid growth in the number of students and the increasing demands on physicians for high-volume patient care. At some point in the future, the US government, accrediting organizations, and medical associations will need to reenvision the clinical training of medical students.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: The STFM Preceptor Expansion Initiative has been supported in part by the American Board of Family Physicians Foundation and the Physician Assistant Education Association.

References

- Theobald M, Ruttter A, Steiner B, Morley CP. Preceptor expansion initiative takes multitactic approach to addressing shortage of clinical training sites. Fam Med. 2019;51(2):159-165. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.379892

- Preceptor Expansion Initiative. Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. Accessed April 20, 2021.https://www.stfm.org/about/keyinitiatives/preceptorexpansion/preceptorexpansioninitiative/

- Association of American Medical Colleges. AAMC Medical School Enrollment Survey: 2019 Results. Published September 2020. Accessed March 11, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/media/47726/download

- Mainous AG III, Seehusen D, Shokar N. CAFM Educational Research Alliance (CERA) 2011 Residency Director survey: background, methods, and respondent characteristics. Fam Med. 2012;44(10):691-693.

- Everard KM, Schiel KZ. Changes in family medicine clerkship teaching due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Fam Med. 2021;53(4):282-284. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.583240

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12 - Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/medicare-claims-processing-manual-chapter-12

- Barreto TW, Eden AR, Hansen ER, Peterson LE. Barriers faced by family medicine graduates interested in performing obstetric deliveries. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(3):332-333. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2018.03.170427

- OMP 2019 Osteopathic Medical Profession Report. American Osteopathic Association. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://osteopathic.org/wp-content/uploads/OMP2019-Report_Web_FINAL.pdf

- ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine Summary and Impact of Major Requirement Revisions. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/reviewandcomment/120_familymedicine-_2021-12_impact.pdf

- Dyrda L. 70% of physicians now employed by hospitals or corporations. Beckers ASC Review. Published July 1, 2021. Accessed March 11, 2022. https://www.beckersasc.com/asc-transactions-and-valuation-issues/70-of-physicians-are-now-employed-by-hospitals-or-corporations.html

There are no comments for this article.