Introduction: A uniform method of iterative professional development for medical educators does not exist in the US graduate medical education system. The Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Faculty Competencies Special Project Team, a subgroup of the Faculty Development Collaborative, sought to create a competency-based assessment framework for medical educators. This paper describes the feasibility and acceptance of a draft competencies resource using a survey.

Methods: A mixed-methods, ten-question survey to assess the feasibility and acceptance of the draft competencies resource was created and distributed to medical educators through educational contacts from October 2019 to November 2019.

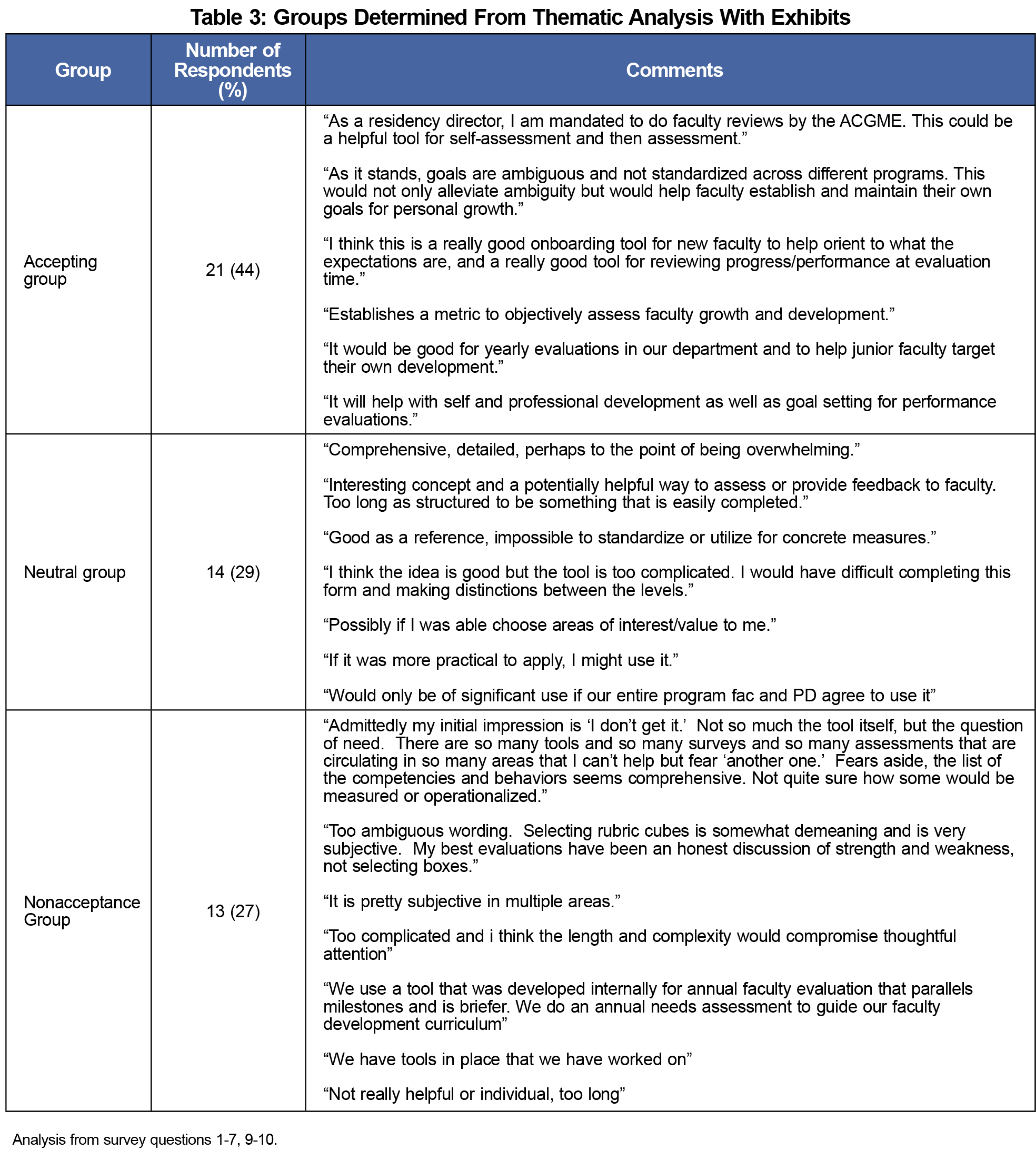

Results: Eighty-six surveys were completed. Of the 86 respondents, 48 (55%) answered all the survey questions. Thematic analysis for acceptance of the draft yielded three groups, the accepting, neutral, and nonacceptance groups. Each group had distinct characteristics regarding the likelihood of accepting and using the draft competencies.

Conclusions: The draft competencies are thought to be feasible, with overall acceptance in the current form. Further research will guide revisions of the competency resource before final distribution.

As residencies frame curricula and evaluation around competency-based medical education (CBME), there are calls for medical educators to view professional development through a similar lens.1-4 Traditionally, faculty success focuses on the clinicians’ breadth of medical knowledge.5,6 Given the expectations of medical educators' expertise beyond clinical knowledge in domains such as teaching, advocacy, and scholarship, there is need for ongoing and iterative professional development.3,4,7-10

A literature review highlighted formal faculty development programs, national conferences, and expert panels that attempt to address this need, but they are uniform in neither content nor delivery. 3-5, 7-11 The Faculty Competencies Special Project Team, a subgroup of the Faculty Development Collaborative within the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM), created a resource that addresses gaps in medical educator professional development. It contains domains and behaviors addressing the diverse skills a medical educator may acquire.12-14

The study objective was to assess the draft faculty competencies using a survey to identify common respondent themes and evaluate the competencies’ comprehensiveness, flexibility, acceptance, and implementation. Study results will be incorporated into the revised version.

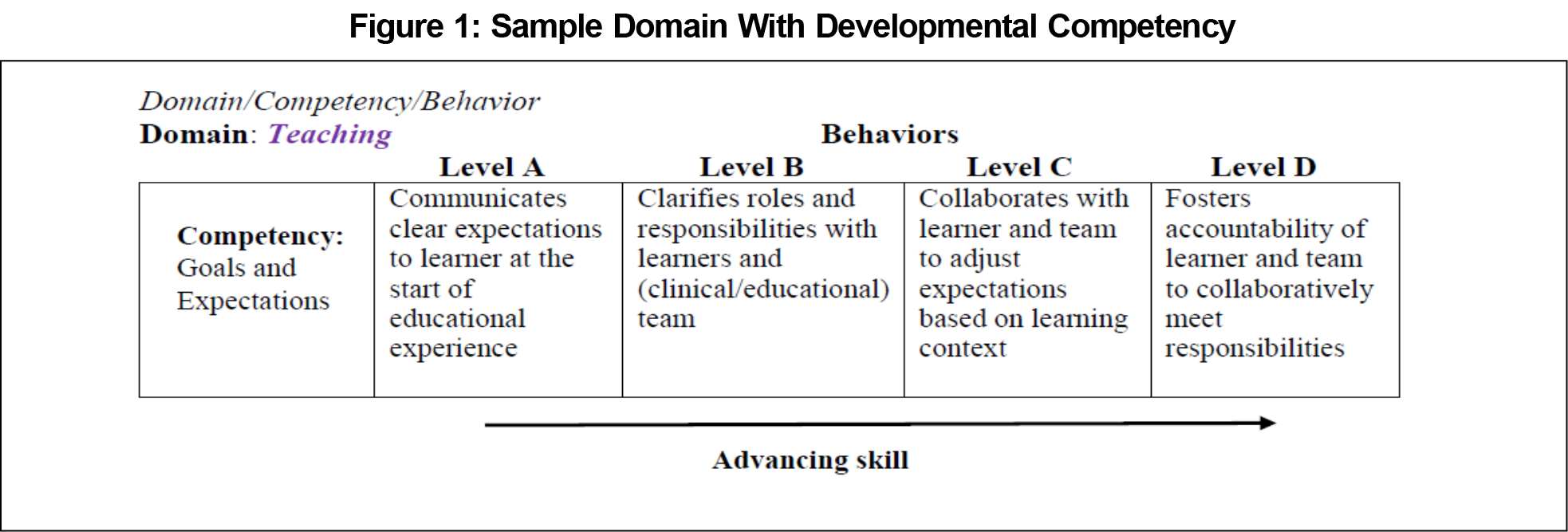

The faculty competencies were collaboratively created by the STFM Faculty Competencies Special Projects Team, supported by a needs assessment and literature review. An example domain is shown in Figure 1.

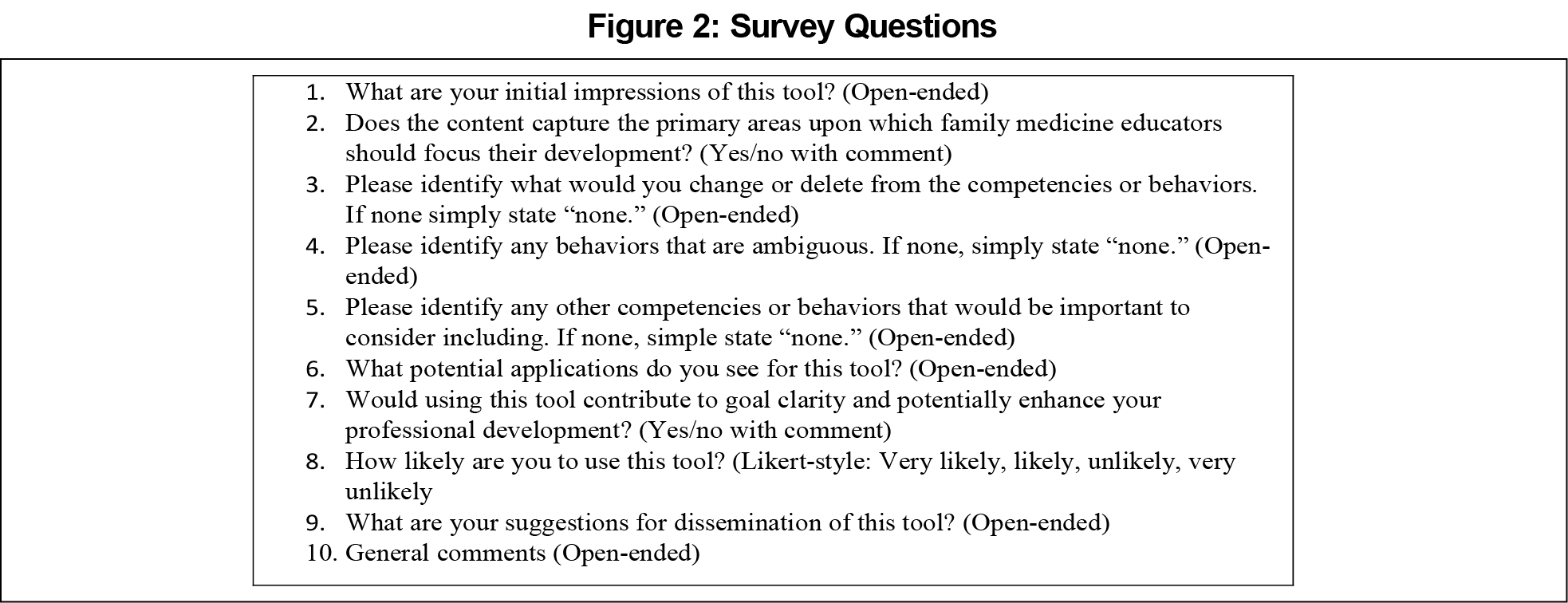

Using a mixed-method study design, we developed a 10-question survey that investigated demographics, feasibility with quantitative Likert scales, and acceptance with qualitative open-ended questions (Figure 2). Prior to dissemination, the survey underwent cognitive testing by steering committee members who reviewed and answered the survey questions to ensure the responses would accurately measure what was intended.15,16

The survey was distributed from October 2019 to November 2019. Distribution occurred through an STFM Faculty Development Collaborative listserv posting and emails to educational contacts of 14 members of the Faculty Development Special Project Steering Committee. Voluntary enrollment concluded once the study investigators determined that thematic saturation was achieved. Thematic saturation was reached when repetition and consistency in survey responses were observed.17 We analyzed quantitative data with standard descriptive and frequency analyses using Microsoft Excel 2020 (Microsoft Corp., Seattle, WA). Three study investigators independently conducted a qualitative thematic analysis of the open response data. After independent review, they compared results and reached consensus on major themes.

The Samaritan Health Services Institutional Review Board reviewed the study protocol and determined it to be exempt.

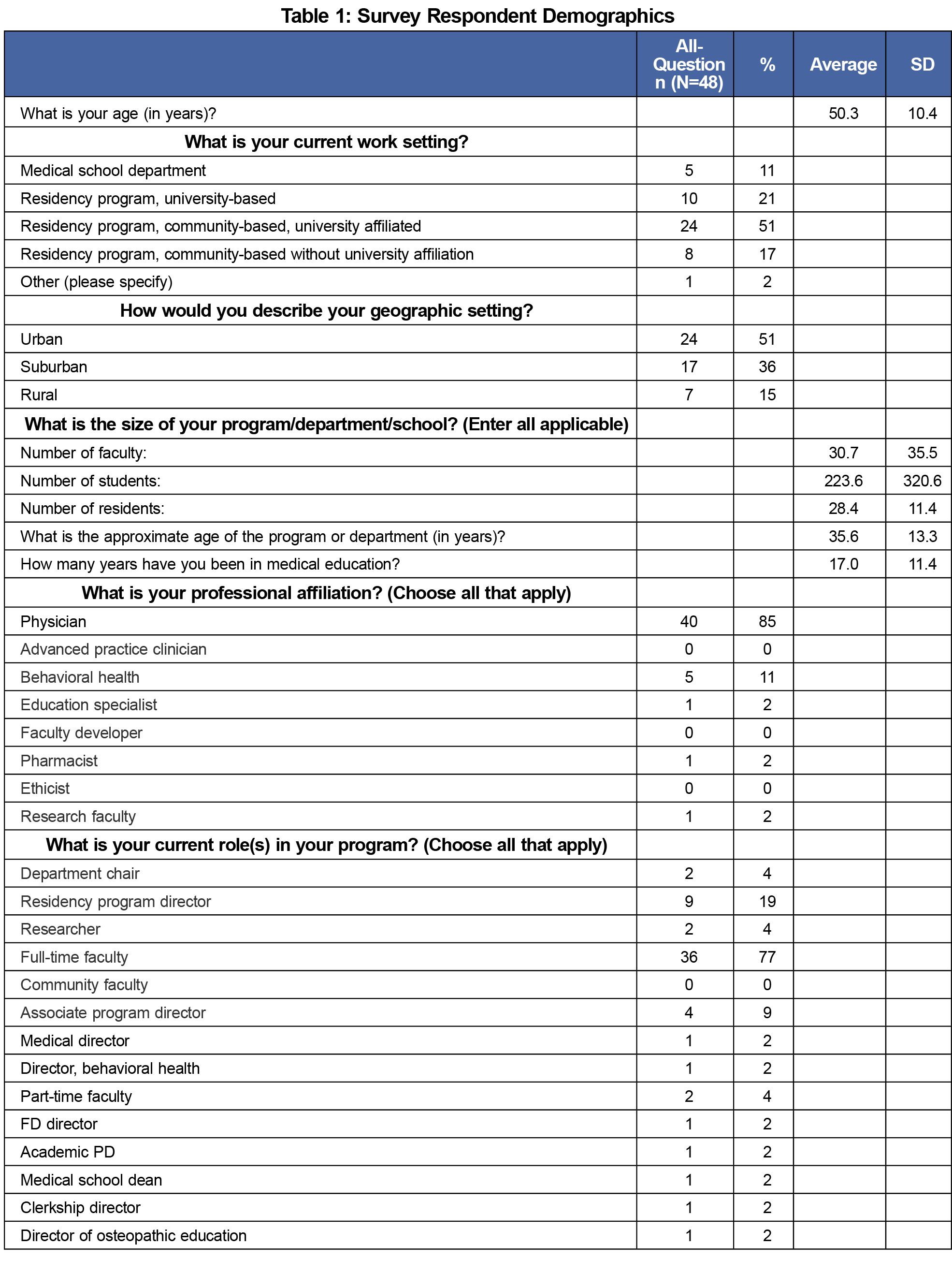

Eighty-six surveys were completed with at least one question answered. Forty-eight (55%) respondents completed all the questions (Table 1). We did not calculate the response rate as the survey was distributed to an unknown number of educational contacts. We excluded incomplete surveys from analysis. A demographic analysis revealed that there were no differences between incomplete and complete survey populations.

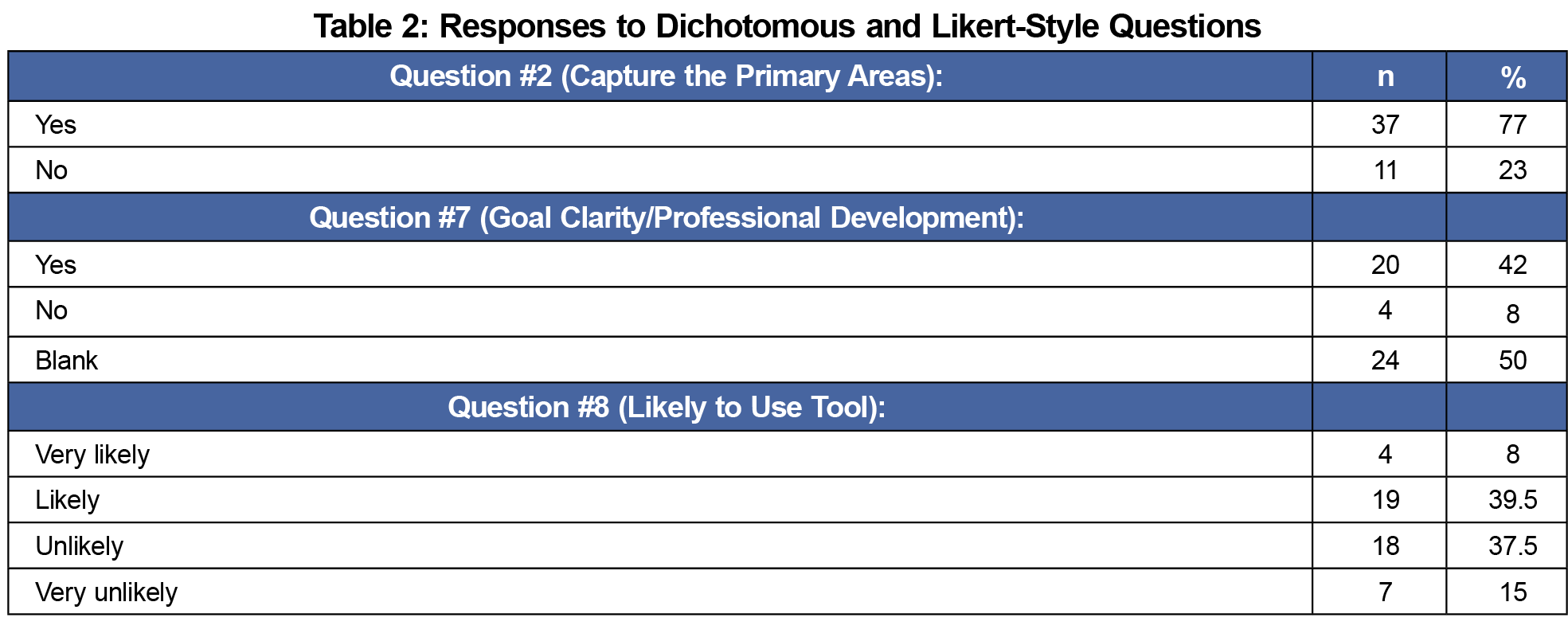

Twenty-three respondents (48%) stated that they were “very likely” or “likely” to use the draft competencies (Table 2).

Three distinct groups emerged from the thematic analysis of the open responses regarding educator acceptance of the faculty competencies (Table 3).

The survey of medical educators to evaluate the feasibility and acceptance of the faculty competencies created by the STFM Faculty Competencies Special Project Team yielded useful information. The mixed-methods survey allowed for quantitative and qualitative data collection. Nuances in discrete and thematic analysis accounted for discrepancies in respondent categorization for feasibility and acceptance. While 48% of respondents found the draft competencies feasible, thematic analysis resulted in differences when addressing willingness to adopt the competencies. The results identified key characteristics of the surveyed cohort who would accept and potentially adopt the content and those who would not accept it.

The nonacceptance group (27%) viewed the competencies as lengthy, complex, ambiguous, and at times redundant. There were concerns with how the competencies would be implemented. This group felt the competencies were unnecessary; rather than enhancing faculty development, they would cause confusion and perhaps even harm. Additionally, respondents in this group had preexisting assessments in place or did not believe in the need for faculty competencies. It would likely require significant revisions to the competencies’ format and content for this group to consider acceptance.

The neutral group (29%) felt the faculty competencies provided a missing faculty development resource. However, the group had concerns about the competencies’ complexity and operationalization within educational programs. In addition, this group wanted clarification around certain domains and behaviors. This group would feel more comfortable using the competencies if further iterations addressed these concerns and reduced ambiguity.

The accepting group (44%) favored the feasibility and acceptance of the competencies. This group agreed they provide an avenue for goal setting, self-assessment, and professional development. The group visualized the competencies’ implementation in several settings, including with new faculty. Thus, this group would likely use the competencies regularly within their educational programs.

Themes identified within the nonacceptance and neutral groups highlight the need to provide instruction on the intent of the competencies. Additionally, the domains and behaviors will be reviewed, revised, and simplified to facilitate understanding. Future iterations will reduce ambiguity and provide a succinct competency resource. Ultimately, the critique of the nonacceptance and neutral groups will be incorporated in future versions with the overall goal of near-universal acceptance.

There are several limitations to this study. Sampling bias and a small sample size with an unknown response rate limit the ability to generalize the quantitative data to a larger population or demonstrate applicability of the qualitative data to other groups from different backgrounds and demographic areas. Future iterations can be improved with larger sample size across multiple disciplines. Additionally, while some groups were neutral to nonaccepting of the competencies, selection bias is still a threat to validity. We attempted to mitigate this possibility by creating questions on similar topics in various forms to triangulate toward a theme.

Future research for the faculty competencies includes a systematic review currently in process that will aid future iterations. Subsequently, we will conduct a modified Delphi study to create a version of the faculty competencies that will be published and disseminated. Once published, an additional, anticipated study would assess faculty behavior change and institutional impact.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Olivia Pipitone, MPH, for her help with structuring the data in Table 1.

References

- Iobst WF, Sherbino J, Cate OT, et al. Competency-based medical education in postgraduate medical education. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):651-656. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2010.500709

- Dath D, Iobst W, Collaborators IC. The importance of faculty development in the transition to competency-based medical education. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):683-686. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2010.500710

- Heath JK, Dine CJ, Burke AE, Andolsek KM. Teaching the teachers with milestones: using the ACGME Milestones model for professional Development. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(2)(suppl):124-126. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-20-00891.1

- Milner RJ, Gusic ME, Thorndyke LE. Perspective: toward a competency framework for faculty. Acad Med. 2011;86(10):1204-1210. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822bd524

- Harris DL, Krause KC, Parish DC, Smith MU. Academic competencies for medical faculty. Fam Med. 2007;39(5):343-350.

- Dickerman J, Sánchez JP, Portela-Martinez M, Roldan E. Leadership and academic medicine: preparing medical students and residents to be effective leaders for the 21st century. MedEdPORTAL. 2018;14:10677. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10677

- Carraccio C, Englander R, Van Melle E, et al; International Competency-Based Medical Education Collaborators. Advancing competency-based medical education: a charter for clinician--educators. Acad Med. 2016;91(5):645-649. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001048

- Hitchcock MA, Stritter FT, Bland CJ. Faculty development in the health professions: conclusions and recommendations. Med Teach. 1992;14(4):295-309. doi:10.3109/01421599209018848

- Leslie K, Baker L, Egan-Lee E, Esdaile M, Reeves S. Advancing faculty development in medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2013 Jul;88(7):1038-45. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318294fd29.

- Steinhart Y. Faculty development in the new millennium: key challenges and future directions. Med Teach. 2000;22(1):44-50. doi:10.1080/01421590078814

- Gonzalo JD, Ahluwalia A, Hamilton M, Wolf H, Wolpaw DR, Thompson BM. Aligning education with health care transformation: identifying a shared mental model of “new” faculty competencies for academic faculty. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):256-264. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001895

- Srinivasan M, Li STT, Meyers FJ, et al. “Teaching as a Competency”: competencies for medical educators. Acad Med. 2011;86(10):1211-1220. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822c5b9a

- Gopal B, Johnson B, Kenyon T, Clark J. Faculty milestones: forming a path to greater accountability and transparency. STFM Resource Library. Posted January 24, 2019. Accessed February 10, 2019. https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/faculty-milestones-forming-a-path?CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a&tab=librarydocuments

- Johnson B, Kenyon T, Boltri J, Gopal B. Bridging the gap: Examining the implications of implementing universal developmental milestones for faculty. STFM Resource Library. Uploaded January 24, 2019. Accessed February 10, 2019. https://resourcelibrary.stfm.org/viewdocument/bridging-the-gap-examining-the-imp-1?CommunityKey=2751b51d-483f-45e2-81de-4faced0a290a&tab=librarydocuments

- Cognitive Testing (presentation slides). Harvard University Program on Survey Research. Accessed May 27, 2022. https://psr.iq.harvard.edu/files/psr/files/CognitiveTesting_0.pdf.

- Cognititive Interviewing. CDC National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed May 27, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ccqder/evaluation/CognitiveInterviewing.html

- Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis. In: Cooper H, Camic PM, Long DL, Panter AT, Rindskopf A, Sher KJ, eds. APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association; 2012. doi:10.1037/13620-004

There are no comments for this article.